John Ford Never Forgot the Way Lee Marvin Looked at John Wayne on The Hawaiian Beach After the Punch

John Wayne hit the floor so hard the cameras stopped rolling. And when the crew rushed over, they found him tangled in the wreckage of a prop table that wasn’t supposed to break. Because Lee Marvin’s fist wasn’t supposed to connect. Wait. Because what happened in the 8 seconds after that punch would mark the end of Hollywood’s greatest director actor partnership.

And nobody on that Hawaiian beach understood it was already over. The morning started like most mornings on the Donovan’s Reef set in the summer of 1963. The air was thick with salt and humidity, the kind that made your shirt stick to your back before you’d even moved. John Wayne stood under a palm tree, smoking a cigarette and watching the grip set up the next shot.

Behind him, the turquoise waters of Kauai stretched out like something from a postcard. And in front of him, John Ford paced back and forth with that familiar megaphone in his hand, barking orders at anyone who got too close. The crew had been in Hawaii for 6 weeks by then, and most of them had stopped noticing the paradise around them.

That’s what happens when you work in beautiful places. After a while, the beaches just become another location. The sunsets just another lighting challenge. But Wayne still noticed. He’d stand there between takes, cigarette in hand, and just stare out at the water like he was trying to memorize it. “You thinking about buying the place?” Someone had asked him the week before.

Wayne had smiled without turning around. “Just looking,” he’d said. “You get to my age, you start paying attention to things you used to take for granted. That morning, the set was loud with the usual chaos of preparation. Hammers banging, someone shouting about a missing prop, the camera operator arguing with his assistant about f-stops and exposure.

Ford’s voice cut through all of it, sharp and impatient. He’d been that way for days now, shorter with people, quicker to snap, less willing to let things slide. Some of the younger crew members thought he was just being forward, cranky, and difficult like always. But the ones who’d worked with him before knew better.

They’d seen this mood before, usually right before he finished a picture and moved on to something else. This was supposed to be easy, a vacation film, some people called it. Ford had even admitted as much to Lee Marvin when he offered him the role, told him it didn’t matter what the story was, it would be a good excuse for everyone to spend 8 weeks in Hawaii this summer.

No Monument Valley this time. No dusty plains or brutal sun or 20-mile rides on horseback. Just tropical breezes, laughs, and a little rough house comedy to keep the Duke looking like the Duke. But that morning, Wayne didn’t look much like the Duke at all. He looked tired. His face was thinner than it had been in Rio Bravo. And when he took a drag from that cigarette, you could see his hand shake just a little before he steadied it.

He was 56 years old. And though nobody said it out loud, everyone on the set knew this would probably be the last time Ford and Wayne worked together. 35 years, 20 films, and now on a beach in Hawaii. It was winding down. Marvin came over and clapped Wayne on the shoulder. Ready to take another beating, Duke? He said with that half grin that made him look dangerous even when he wasn’t trying. Wayne smiled back.

Long as you remember, it’s just a movie, Lee. Marvin laughed and pulled out his own pack of cigarettes. They stood there together for a moment. Two men in Hawaiian shirts on a beach that looked like something from a travel brochure. And for just that second, it was easy to forget they were actors playing parts.

“You know what’s funny,” Marvin said, lighting his cigarette. “Last year, I was trying to kill you. This year we’re best friends. That’s Hollywood. Wayne said yesterday’s villain is tomorrow’s drinking buddy. Speaking of which, Marvin took a drag. You think Ford’s all right? He’s been fee trailed off searching for the word different. Wayne finished for him.

Yeah, different. Wayne didn’t say anything else. He just smoked his cigarette and watched Ford yell at someone about the placement of a camera dolly. Look at this moment. Because what neither of them knew was that Ford wasn’t just being difficult. He was already saying goodbye one sharp word at a time. And nobody understood that yet.

They’d worked together the year before on the man who shot Liberty Valance. And Marvin had been the villain then. Cold, brutal, the kind of man who’d whip you for sport. But here on Donovan’s Reef, they were old Navy buddies throwing punches at each other every year on their birthdays just for laughs. It was supposed to be fun.

That was the whole point. Two aging warriors reliving their glory days in a tropical paradise, trading fake blows and real laughs while the cameras rolled. Except nothing felt particularly funny that morning. Maybe it was the heat. Maybe it was the fact that they’d been shooting for 6 weeksand everyone was tired.

Or maybe it was something else, something nobody wanted to name out loud. Ford called them over to the set, a makeshift bar they’d built near the water’s edge. There were tables, chairs, a few extras dressed as island locals, and a whole lot of breakaway furniture that was designed to shatter on Q. The scene was simple. Wayne and Marvin would brawl, knock over a few chairs, crash into the bar, and end up on the floor laughing.

Comedy gold. The kind of thing audiences would eat up. All right, let’s run through this once, Ford said. Not looking at either of them, he was focused on the camera angle, the light, the way the waves were hitting the shore behind them. Details, always details. John, you come in from the left. Lee, you throw the first punch.

Make it look good, but keep it safe. We don’t have time to reset if something breaks. Wayne nodded. Marvin nodded. They’d done this dance a hundred times before. The assistant director called for quiet on the set, and suddenly the only sound was the ocean and the hum of the camera starting to roll. Notice something here because this is where the story splits into two directions and only one of them ends with Wayne on the floor.

Marvin came in fast, maybe too fast. His footwork was solid. The kind of thing you learn from years of stage combat, but there was something in his eyes that suggested he wasn’t entirely in control. Later, people would argue about whether he meant to connect or whether it was pure accident. But in that moment, with the cameras rolling and the ocean crashing behind them and Ford watching through the viewfinder, none of that mattered.

Wayne saw the fist coming. His body started the defensive movement automatically, weight shifting back, chin tucking down, shoulders rolling to absorb the blow that wasn’t supposed to land. But his timing was off. Not by much. Half a second, maybe less. the kind of margin that wouldn’t have mattered 5 years earlier, 10 years earlier, 20 years earlier when his reflexes were faster and his body moved the way he told it to.

But 56 isn’t 36 and half a second is all it takes. The uppercut that was supposed to stop 2 in from his chin kept going. It connected. Not hard enough to knock him out, but hard enough to snap his head back [music] and send him stumbling into the table behind him. Wayne felt his heel catch on something. Maybe a piece of driftwood someone had left on the set.

Maybe just uneven sand. His arms went out for balance, reaching for something that wasn’t there. Time did that thing it does in moments like this where everything slows down and speeds up at the same time. Wayne saw the edge of the table coming toward him. He felt his body turning, trying to land in a way that wouldn’t hurt, trying to protect his back, his neck, trying [music] to do what stuntmen do when falls go wrong, but the table wasn’t where it was supposed to be.

Or maybe he wasn’t where he was supposed to be, and his full weight came down on the edge of it at exactly the wrong angle. The table wasn’t supposed to break. It was a prop, sure, but it was solid wood, reinforced, built to take a hit. Except Wayne’s full weight came down on the edge of it at exactly the wrong angle, and the whole thing gave way beneath him.

He went through it like it was made of cardboard, arms flailing, and hit the sand hard with pieces of the table scattered around him like shrapnel. The cameras kept rolling for maybe two more seconds before the operator realized something was wrong. Then everything stopped. Ford didn’t yell. That was the first sign that this wasn’t just another blooper.

He walked over slowly, megaphone hanging at his side, and looked down at Wayne sprawled out on the sand with one hand pressed to his jaw and the other braced against the ground. “You all right, Duke?” Ford’s voice was quiet. Too quiet. Wayne didn’t answer right away. He was testing his jaw, moving it side to side, checking for breaks.

Then he looked up at Marvin, who was standing there with his fist still clenched and his face white as a sheet. “Didn’t pull it, did you?” Wayne said finally. Marvin opened his mouth, closed it, then shook his head. “I thought you were. I thought you’d move.” “I tried.” Wayne pushed himself up to sitting, brushed some sand off his shirt, and spit blood into the dirt.

Not a lot, just enough to make everyone on the set go dead silent. One of the grips stepped forward to help him up, but Wayne waved him off. I’m fine. Let’s go again. Ford didn’t move. He just stood there looking at Wayne like he was trying to solve a puzzle that didn’t have an answer. Then he turned to the assistant director.

Take 15. Get some ice. Wayne started to protest, but Ford held up a hand. 15 minutes, John. That’s not a request. Listen, because this is the part where you need to understand what was really happening. This wasn’t just about a punch that landed wrong or a table that broke when it shouldn’t have.

This wasabout two men who’d built an entire mythology together. And now they were standing on a beach in Hawaii watching it fall apart in real time. Ford walked away from the set [music] down toward the water and Wayne watched him go. Marvin stood there looking like a man who just shot his best friend by accident and the rest of the crew busied themselves with resetting the furniture and pretending they hadn’t seen anything.

A production assistant brought over a bag of ice wrapped in a towel and Wayne pressed it against his jaw without saying anything. His eyes were still on Ford’s back. The way the old man’s shoulders were hunched forward like he was carrying something heavy. He’s getting old, someone muttered behind Wayne. He didn’t turn around to see who said it.

The 15 minutes stretched into 30. Wayne sat in a folding chair under the palm tree, smoking another cigarette and holding ice to his face. Marvin came over twice to apologize, and both times Wayne told him to forget about it. But Marvin couldn’t [music] forget about it. You could see it in his eyes. The same look he’d had in Liberty Valance when he realized Stuart’s character wasn’t backing down.

Fear maybe, or something close to it. When Ford finally came back, he didn’t look at Wayne. He just nodded at the assistant director and said, “Let’s shoot it. You sure?” the assistant director asked, glancing between Ford and Wayne. I said, “Let’s shoot it.” So, they shot it. Three more takes and in every single one, Marvin pulled his punches so far back that it looked like he was shadow boxing.

Ford didn’t say anything about it. Wayne didn’t say anything about it, but everyone on that set knew the scene was ruined. By the time the sun started to set, they’d moved on to a different sequence. Wayne and Marvin sitting at the bar laughing about the fight they just had. The irony wasn’t lost on anyone.

There they were pretending to be old friends who’d just beaten the hell out of each other for fun. And in reality, there was blood drawing on Wayne’s lip and Marvin looked like he wanted to disappear into the ocean. Ford called cut and announced they were done for the day. The crew started packing up equipment and Wayne stood there for a moment watching them work.

Then he walked over to where Ford was sitting in his director’s chair, staring out at the water. Happy, Wayne said quietly. Ford didn’t look at him. What? This the last one? There was a long pause, long enough that the waves crashed twice and someone dropped a piece of equipment on the other side of the set.

“Yeah,” Ford said finally. “This is the last one.” Wayne nodded. He didn’t ask Ford to explain or try to change his mind. He just nodded, turned around, and walked back toward his trailer. Remember this because years later, people would ask why Ford and Wayne never worked together again after Donovan’s reef.

They’d point to Ford’s age, to Wayne’s cancer, to scheduling conflicts and different visions. All of that was true. But the real answer was simpler than that. It was the punch, not the fact that it landed, but the fact that Wayne couldn’t move fast enough to avoid it. The table breaking wasn’t just bad luck.

It was proof that time catches everyone eventually, even legends. And Ford saw it. He saw his friend, his star, his duke, go down hard because his reflexes weren’t what they used to be. And he knew right then that the partnership had run its course. That night, after the crew had gone back to their hotels and the beach was empty, except for a few locals fishing off the rocks, Wayne sat on the steps of his trailer with a glass of whiskey, and looked out at the ocean, his jaw still hurt, not bad, but enough to remind him every time he moved his mouth. Marvin

walked over with his own glass and sat down next to him without asking. For a while, neither of them said anything. I’m sorry, Marvin said eventually. Wayne took a sip of his whiskey. Already told you to forget it. Can’t. Then that’s your problem, not mine. Another wave crashed. Another minute passed.

He’s not going to call me again, is he? Wayne said, not looking at Marvin. Marvin didn’t have to ask who he meant. Probably not. Wayne finished his drink and set the glass down on the step beside him. 35 years, he said quietly. 20 films and it ends on a beach in Hawaii with me going through a table. Could have ended worse, could have ended better.

They sat there until the stars came out [music] and then Marvin stood up, clapped Wayne on the shoulder, and went back to his own trailer. Wayne stayed a little longer, smoking one more cigarette and listening to the sound of the ocean. >> [music] >> The next day, they were back on set shooting the rest of the film. Everything went smoothly.

No more punches landing, no more tables breaking, no more blood in the sand. Ford directed with the same precision he always had, and Wayne performed with the same charisma. To anyone watching, it looked like business as usual. [music]But something had changed. You could feel it in the spaces between takes, in the way Ford would walk past Wayne without stopping to joke around.

In the way Wayne would check over his shoulder before doing a stunt to make sure someone was ready to catch him if he fell. Wait, because this is where the real story lives in the quiet moments that don’t make it into the final cut. One afternoon, about 2 weeks after the incident with the table, they were shooting a scene where Wayne had to jump off a low wall onto the sand.

It was nothing really, a 3-FFT drop that any stuntman could do in his sleep. But Wayne stood on that wall for a solid 30 seconds before he jumped. And when he landed, he stumbled just slightly before catching himself. Ford saw it. Wayne knew Ford saw it, but neither of them said a word. The film wrapped in late summer and everyone flew back to Los Angeles with tans and stories about the easiest shoot they’d ever been on.

Donovan’s Reef would go on to be a modest success, not a masterpiece, not a disaster, just a solid comedy that people enjoyed and then forgot about. Critics called it lightweight. Ford’s fans called it a vacation movie. And maybe they were right. But for Wayne and Ford, it was something else entirely. It was proof that everything ends, even partnerships that feel like they’ll last forever.

It was a table breaking under the weight of time, a punch that landed when it shouldn’t have, and two men standing on a beach realizing they’d already said goodbye without meaning to. Ford went on to make two more films, Cheyenne Autumn and Seven Women, but neither of them featured Wayne. He died in 1973 at the age of 78, having spent his final years working on documentaries and wondering [music] maybe what else he could have made if he’d had more time.

Wayne kept acting for another 16 years, starring in True Grit, The Cowboys, The Shudest, and a dozen others. He won his Oscar. He became even more of a legend, but he never worked with Ford again. Whenever someone asked him why, he’d just shrug and say something vague about scheduling or creative differences. He never mentioned the table.

He never mentioned the punch. And he never mentioned the way Ford looked at him that afternoon on the beach like he was seeing something he didn’t want to see. But the people who were there, the ones who saw Wayne hit the floor and watched Ford walk away, they knew. They knew that the greatest director actor partnership in Hollywood history didn’t end with a dramatic fight or a tearful goodbye.

It ended with 8 seconds of confusion on a Hawaiian beach, a prop table in pieces, and the understanding that some things can’t be fixed no matter how much you want them to be. Years later, after both men were gone, someone asked Lee Marvin if he remembered the punch. He said he did.

He said he’d been trying to forget it for decades. “It wasn’t my fault,” he told them. “But it felt like it was.” They asked him what he meant by that, and he shook his head. “You had to be there,” he said. “You had to see the way Duke looked at Ford after it happened, like he was apologizing for getting old.

” “Listen to what this really means, because that look Marvin described is the thing cameras never capture. the moment that explains why legends are just men who haven’t run out of time yet. If you enjoyed spending this time here, I’d be grateful if you’d consider subscribing. A simple like also helps more than you’d think. And maybe that’s the real story.

Not the punch itself, but what it represented. The moment when even John Wayne couldn’t pretend he was invincible anymore, and John Ford couldn’t pretend he didn’t notice. So, if you’re looking for a happy ending, you won’t find it here. But if you’re looking for the truth, it’s this. On a beach in Hawaii in 1963, two legends filmed their last scene together.

And nobody applauded when they said cut for the final time. They just packed up their equipment, got on their planes, and went home to separate lives that would never intersect again. The table was thrown away. The bruise on Wayne’s jaw healed. The film came out and did fine, but the partnership was over. Finished by a punch that landed and a fall that nobody could take back.

That’s how it ended. Not with a bang, not even with a whimper. Just with the sound of wood breaking and waves crashing and two men who’d made history together, realizing they’d run out of time. If you want to hear what Ford whispered to Wayne during the rap party that nobody else understood until years later, let me know in the comments.

News

Lee Van Cleef Finally Tells the Truth About Clint Eastwood

Lee Van Cleef Finally Tells the Truth About Clint Eastwood Lee Vancliffe finally tells the truth about Clint Eastwood. Lee…

Arab Billionaire Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Don’t Belong Here’ — Instantly Regrets It!

Arab Billionaire Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Don’t Belong Here’ — Instantly Regrets It! When the doors of Leardam, one of…

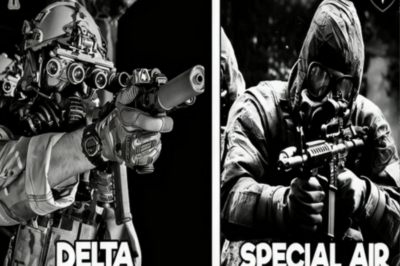

Why Delta Force HATES Training with the SAS

Why Delta Force HATES Training with the SAS America’s most elite soldiers learned everything from the British SAS. Yet every…

Bikers Thought He Was Just Another Old Man — Then Realized It Was Ozzy Osbourne…

Bikers Thought He Was Just Another Old Man — Then Realized It Was Ozzy Osbourne… Picture this. A lonely gas…

WHAT JAPAN’S LEADERS ADMITTED When They Realized America Couldn’t Be Invaded

WHAT JAPAN’S LEADERS ADMITTED When They Realized America Couldn’t Be Invaded In the stunned aftermath of Pearl Harbor as Japanese…

Street Kid Playing “Mama, I’m Coming Home” When Suddenly Ozzy Osbourne Showed Up

Street Kid Playing “Mama, I’m Coming Home” When Suddenly Ozzy Osbourne Showed Up When the first notes of, “Mama, I’m…

End of content

No more pages to load