Murder in the Happy Valley: Hedonism, Power, and the Fall of an Earl

In the first half of the 20th century, life in colonial Kenya unfolded along a stark divide. For native Kenyans, British rule brought land seizures, forced labor, and legislation designed to cement inequality. For the British settlers—especially the wealthy aristocrats fleeing cold weather, political pressures, or high taxes at home—Kenya offered sprawling estates, cheap labor, and the freedom to indulge in every imaginable excess. Nowhere was this more evident than in the Happy Valley, a region whose hedonistic social set became infamous for its parties, affairs, drug use, and sense of absolute impunity.

It was within this gilded world of decadence that one of Kenya’s most notorious mysteries would erupt: the 1941 murder of Jocelyn Haye, the 22nd Earl of Erroll.

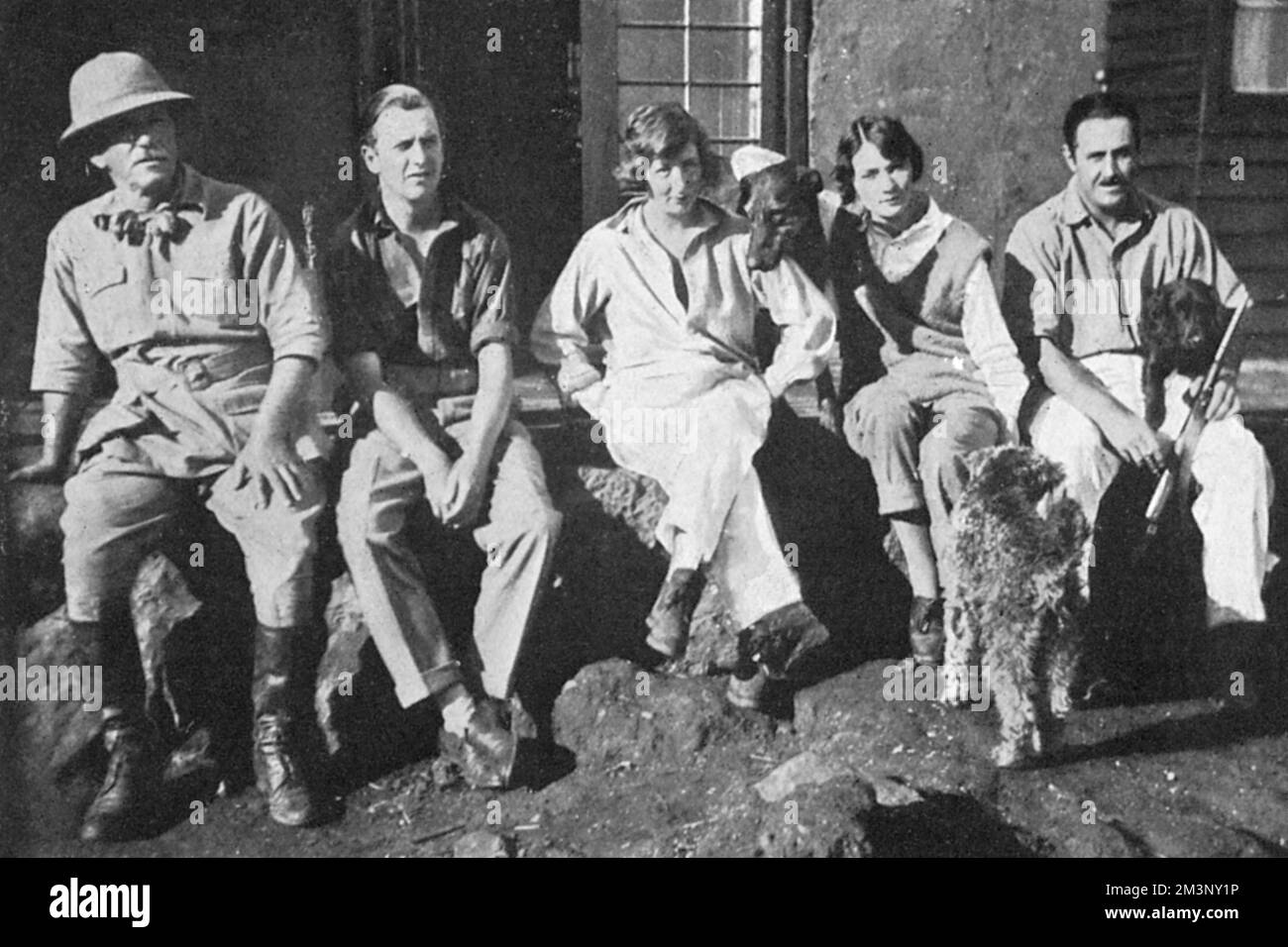

Haye had arrived in Kenya in 1924 with his bride, Adena Sackville. Their scandalous marriage—Adena was wealthy, twice divorced, and older than he—caused such social uproar in Britain that the couple fled to Kenya for a fresh start. There, in their bungalow near the Aberdare Mountains, they were soon absorbed into the Happy Valley set. The rules that governed polite British society held no weight here. Instead, the settlers operated in a world defined by privilege, entitlement, and vice.

The era’s most colorful characters made even their aristocratic peers blush. Lord Delamere rode his horse through the dining room of Nairobi’s Norfolk Hotel. Kiki Preston, known as “the girl with the silver syringe,” injected drugs openly in public. Countess Alice de Janz shot a man who declined her marriage proposal—and was fined the equivalent of just four U.S. dollars. Affairs, orgies, and vengeful romantic feuds were so ubiquitous that a dark joke circulated: “Are you married, or do you live in Kenya?”

Haye’s own marriages reflected the turbulence of the colony’s elite. After divorcing Adena, he married Molly Ramsay-Hill, whose struggles with addiction led to her death in 1939. Politically, he wavered too; though he briefly joined the British Union of Fascists, he later embraced a patriotic role in Kenya’s wartime administration.

The final act of this story began when Diana Caldwell entered the scene. A glamorous London model and pilot, Diana married Henry John “Jock” Delves Broughton—an aging baronet who promised her wealth, status, and even a prenuptial agreement ensuring her financial support should she fall in love with another man. Within weeks of their arrival in Kenya, she found exactly that man: Jocelyn Haye.

The two embarked on a passionate and very public affair, sending Jock into humiliation and desperation. He begged Diana to stay, even offering to leave Kenya so she could pursue her romance without ending their marriage. When that failed, he pleaded with Haye directly—another rebuff.

Finally, on January 23, 1941, Jock invited the lovers to dinner at the Muthaiga Country Club. He appeared gracious, even raising a toast to their future marriage. After dinner, Haye drove Diana back to Jock’s home, dropping her off just before 3 a.m.

Hours later, the Earl of Erroll was found dead in his Buick on a deserted Nairobi road—shot in the head at point-blank range.

Suspicion fell on Jock immediately. He was arrested and put on trial in a sweltering Nairobi courtroom, where he defended himself for 22 hours. The evidence was troubling but circumstantial. Witnesses claimed he had handled weapons shortly before the murder, and that he may have destroyed evidence in a bonfire. Yet other testimony suggested he was physically incapable of scaling a window or running miles to stage the crime. With no murder weapon, no eyewitness, and no conclusive proof, Jock was acquitted.

But acquittal did not bring redemption. Diana left him, and months later he returned to England alone, where he died by suicide—fueling public suspicion that he had pulled the trigger.

For decades, the case lingered in uncertainty, fed by rumors involving jealous husbands, scorned lovers, and even British intelligence. Haye’s known connections to fascist circles gave rise to theories of an MI6 execution. But in 2007, new recordings surfaced suggesting a different truth: that Jock had indeed committed the murder, aided by a Bulgarian doctor who unknowingly helped him escape the scene, and that key witnesses had hidden evidence for years.

Still, as with all stories emerging from the decadent fog of Happy Valley, absolute certainty remains elusive. The murder of the Earl of Erroll endures as a symbol of a colonial world built on secrecy, privilege, and excess—where justice was often just another casualty.

News

Erika Kirk Allegedly Caught in Yet Another Lie — Conflicting Claims About Charlie Kirk’s Texts That “Predicted” His Murder Raise Alarming Questions

This transcript is another monologue by Jimmy Dore, focusing on the ongoing controversy surrounding Charlie Kirk’s 2022 murder, Candace Owens’…

Shapiro & Bari Weiss Take Shots at Megyn Kelly — Her Explosive Clapback Steals the Show!

This is the same transcript from Jimmy Dore’s monologue as in the previous query. Since no new content or reasoning…

Shapiro & Bari Weiss Take Shots at Megyn Kelly — Her Explosive Clapback Steals the Show!

This is the same transcript from Jimmy Dore’s monologue as in the previous query. Since no new content or reasoning…

CH2. LEGAL EARTHQUAKE: MICHELLE OBAMA’S $100M CASE AGAINST SEN. KENNEDY CRASHES DOWN WHEN ONE WITNESS UNLEASHES A 9-SECOND TRUTH NUKE

LEGAL EARTHQUAKE: MICHELLE OBAMA’S $100M CASE AGAINST SEN. KENNEDY CRASHES DOWN WHEN ONE WITNESS UNLEASHES A 9-SECOND TRUTH NUKE Michelle…

Tucker Expertly DESTROYS Ben Shapiro At TPUSA AMFEST!

Conspiracies Surrounding the Assassination They someday may be asked to denounce you and that friendship is not a reason to…

Erika Kirk PANICS! Flies To Nashville For Meeting With Candace Owens!

This is them panicking and melting down. That’s what this is. When you see Erica Kirk get on a jet…

End of content

No more pages to load