The debate over “clean” versus “dirty” hockey is as old as the Stanley Cup itself. Every champion, every dynasty, every iconic player has been scrutinized, criticized, and vilified at one point or another for bending the rules, elbowing opponents, or otherwise skating on the edge of legality. From the Broad Street Bullies of the 1970s to the Florida Panthers’ controversial runs in recent seasons, the perception of dirty play is as much a part of the sport’s narrative as the goals, saves, and championships themselves.

Consider the 2024–2025 season, which ended with six notable suspensions tied directly to on-ice discipline. Aaron Ekblad received a two-game suspension for a playoff elbow on Brandon Hegel, while Hegel himself had been suspended for interference on Sasha Barkov. Pulary picked up two playoff games for an illegal check to the head on Mitchell Chaffy, and Darnell Nurse was suspended one game for cross-checking Quinton Biffield. Paul Carter and Connor Zeri rounded out the list with illegal hits on Adam Pelic and Elias Patterson, respectively. Two of these suspensions involved Florida Panthers players, highlighting how winning teams often draw the most scrutiny.

It is worth noting that these suspensions are not new; every season carries its share of controversial calls. Historically, the scrutiny often intensifies for top teams because victories magnify every borderline play. If a lower-ranked team executes the same hit, it rarely makes headlines. Florida’s 2024 Stanley Cup win, for instance, sparked countless debates over “dirty play,” echoing controversies surrounding the Vegas Golden Knights in 2023, the Colorado Avalanche in 2022, and Tampa Bay Lightning in 2020–2021.

The historical record offers even more perspective. The Flyers of the 1970s, notorious as the Broad Street Bullies, are often cited as the league’s dirtiest team. Their approach, however, had roots in Montreal’s dynastic Canadiens, who set early precedents for physical intimidation. From there, the Islanders of the early ’80s adopted a similarly aggressive style, followed by perennial critiques of the Boston Bruins. While some Bruins players earned reputations as dirty, many modern assessments show that the label is often over-applied, depending on fan bias and team success.

Hall of Famers have not been exempt from these debates. Gordie Howe, a legend of physicality, would likely face suspensions if he played under today’s rules. Maurice “Rocket” Richard, despite his revered status in Montreal, occasionally earned suspensions during high-stakes playoff moments. Scott Stevens walked the line carefully — delivering punishing hits that were legal at the time, yet would be penalized under modern standards. Other notorious players include Matt Cook, Chris Simon, Marty McSorley, Ryan Hullwig, Claude Lemieux, and Dale Hunter, whose actions sometimes crossed into the violent and indefensible.

For goaltenders, reputations mattered just as much. Billy Smith and Ron Hextall both exemplified the lethal crease presence that deterred opponents, while Rick Tocchet carried the Flyers’ hard-nosed ethos into the mid-1980s. Even players often described as “rats” — Ken Linseman, Sam Bennett, and Marshon — found ways to disrupt games without drawing permanent penalties, highlighting the nuanced line between strategic aggression and outright dirty play.

Modern NHL stars also navigate this fine line. Players like Tom Wilson, Evander Kane, Jacob Trouba, and Corey Perry occasionally cross into aggressive, borderline-illegal territory. While suspensions are fewer than in past decades, the intensity and visibility of social media magnify every controversial play. Marshon, for instance, has cleaned up his game over time, yet retains the reputation of a player who can tilt a match with a single emotional outburst.

The NHL itself has evolved to address these issues, though inconsistently. Players can be fined up to 50% of a day’s salary, with caps on first and second offenses, while suspensions serve as escalating deterrents. Yet, fans often perceive bias in enforcement, especially when high-profile teams are involved. History demonstrates that accusations of favoritism or deliberate targeting of certain players are recurring themes, extending back to the 1950s.

Statistically, hockey is cleaner than it once was. Power plays per team per game have declined steadily: 5.46 in 1987–88, 5.04 in 1995–96, 4.24 in 2003–04, and just 2.71 in 2024–25. Referees exercise discretion, and while player safety has improved, debates over what constitutes “dirty” play remain central to the fan experience.

This tension between aggression and legality defines the NHL’s character. Stanley Cup winners are often the most hated teams because they combine skill with calculated physical intimidation. The Boston Bruins of 2011, the Washington Capitals of 2018, and the Los Angeles Kings of 2012 and 2014 were all viewed as “dirty” by opposing fan bases. Conversely, teams that win unexpectedly, like the St. Louis Blues in 2019, often escape the same level of scrutiny.

Ultimately, hockey’s history demonstrates a constant evolution of toughness, perception, and enforcement. Players of the past relied on raw physicality; today’s stars rely on strategy, situational aggression, and social media awareness. The enforcer era has faded, junior leagues no longer produce players strictly for intimidation, and referees enforce rules with a combination of discretion and technology. Yet, the debate persists: which plays cross the line, which teams dominate unfairly, and who earns the label of “dirty”?

For fans, analysts, and historians alike, this is part of hockey’s enduring allure. Every Stanley Cup run carries controversy, every hit sparks conversation, and every championship team balances on the knife-edge of legality and aggression. From Gordie Howe to Marshon, from the Broad Street Bullies to today’s Panthers, hockey’s history is inseparable from the drama of crossing the line. And as long as winning is the ultimate goal, that drama will never fade.

News

NHL Reporter Anna Dua Suffered a Brutal Face-Plant Right In Front Of The Entire New York Rangers Team, And It Was All Caught On Camera [VIDEO]

Anna Dua might look good, but it doesn’t mean she always has the best days. During the start of the…

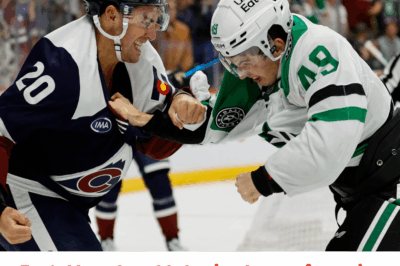

Brutal bare knuckle boxing league for on-ice hockey fights with ‘effective aggressiveness’ leaves fans divided

Clips from the event combining hockey and boxing have got fans talking FANS are on the fence over a brutal…

James Franklin breaks silence on Penn State firing and $49m payout – ‘I was in shock, it feels surreal’

JAMES FRANKLIN has broken his silence on being fired by Penn State. The college football coach will be handed a staggering $49million payout…

Everyone Is Losing Their Mind Over Taylor Swift’s Bold Workout Look: Chunky Gold Chain & Tank Top

Taylor Swift (Photo via Twitter) A clip of Taylor Swift working out has social media in a trance. The international…

Carson Beck Throws His Miami Teammate Directly Under The Bus After Costly Play In Loss To Louisville [VIDEO]

Carson Beck (Photo Via X) When frustration hits, it shows. For Miami quarterback Carson Beck, it was obvious after Friday night’s…

Breaking:4 Fever Players NOT GUARANTEED ROSTER SPOTS IMMEDIATELY MUST GO…

The lights of Gainbridge Fieldhouse had barely cooled when the reality of the offseason began to settle over Indianapolis. For…

End of content

No more pages to load