Japanese Troops Shocked by 12 Gauge Shotguns!

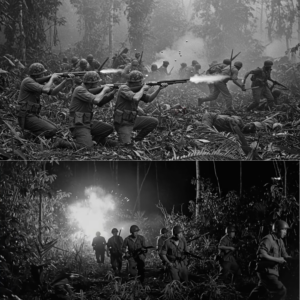

November 2nd, 1943. Buganville Island, Solomon Islands. The jungle air hung thick as wet cloth against Private Tanaka’s face as he crept through the undergrowth. His type 38 rifle held at the ready, 18 in of steel bayonet gleaming faintly in the moonlight. Around him, 11 men of the 23rd Infantry Regiment moved like ghosts through the darkness. This was their element.

For 3 years, Japanese night fighters had terrorized Allied forces across the Pacific. Masters of silent infiltration and sudden savage close combat. Tanaka smiled grimly, remembering his sergeant’s words. The Americans fear the darkness. They huddle in their foxholes, dependent on their machines and ammunition. But we are the night itself.

Distant artillery rumbled like summer thunder. American 105s Tanaka recognized, firing blind harassment rounds. Let them waste their shells. His squad would be among them soon. bayonets finding soft flesh in the darkness. The Americans always broke when the cold steel came. Then it happened. A sound unlike anything in three years of combat.

An explosion of noise so close it seemed to come from inside his skull. Not the sharp crack of a rifle, but a roar that filled the jungle. The vegetation to his left simply disappearing, shredded by something that defied understanding. The Japanese military’s confidence in close combat wasn’t mere bravado. It was doctrine drilled into every soldier from their first day of training.

At the Imperial Army Academy, cadets spent 32 hours each week practicing bayonet techniques compared to just 8 hours on marksmanship. The 1942 Infantry Manual stated bluntly, “The spiritual strength of the Japanese soldier makes one man equal to 10 enemies. Western soldiers corrupted by material comfort cannot withstand the shock of cold steel.

” This wasn’t propaganda for public consumption. Internal military assessments from 1941 dismissed American forces as spiritually weak, dependent on mechanical warfare, incapable of matching the Japanese warrior in tests of individual courage. Colonel Masanobsuji, architect of Japan’s Malayan campaign, wrote in his tactical analysis, “The Americans hide behind their machines.

When forced to fight man-to-man, they crumble like wet paper. The evidence seemed overwhelming. In China, Japanese bayonet charges had shattered numerically superior forces. In the Philippines, American and Filipino troops had fled before bonsai attacks. At Singapore, 30,000 British troops surrendered to a smaller Japanese force that had simply outfought them at close quarters.

Every Japanese soldier memorized the Bushidto principle. The way of the warrior is death. They trained to embrace combat at arms length where spiritual strength mattered more than industrial production. While Americans counted ammunition, Japanese soldiers counted the hours spent perfecting the thrust, parry, and killing stroke.

Lieutenant General Harukichi Hayakutake, commanding Japanese forces in the Solomons, summarized the prevailing wisdom in October 1943. Night belongs to the Japanese soldier. In darkness, when American technology fails, our spiritual superiority becomes absolute. One Japanese soldier with a bayonet is worth a squad of Americans with their machines.

The first warnings came from Guadal Canal, though few Japanese commanders recognized them as such. On August 21st, 1942, 9 days after the Marine landing, Sergeant Yoshio Takahashi led his squad in a pre-dawn infiltration near the Iloo River. Moving through Kunai grass toward marine positions, supremely confident. Then came a sound none of them had heard before.

A metallic chunk chunk followed by a roar that seemed to fill the entire jungle. Private Kenji Nakamura, one of three survivors, later wrote in his diary, “Sergeant Takahashi simply disappeared. Where he had been standing, there was only red mist and shredded vegetation. The thunderstick spoke again, and Corporal Ido was thrown backward as if kicked by an invisible giant.

” The Marines of Edson’s raiders had brought something new to the Pacific. Winchester model 97 pump-action shotguns loaded with double lot buckshot. Corporal Jim Bradley manning one of these weapons that night recalled. They came at us screaming, bayonets flashing. At 30 yards, I started firing. The buckshot spread out like a steel net.

Each shell put 933 caliber balls down range. You couldn’t miss. Initial Japanese report struggled to comprehend what they’d encountered. Captain Akira Yamamoto’s afteraction report from August 23rd described a weapon of multiple projectiles effective at night combat ranges wielded without honor by Marines who refuse proper combat.

He recommended that this cowardly device be countered by increased spiritual determination and faster movement. But the Marines kept their shotguns talking. During the Battle of Bloody Ridge in September, Marine raiders stopped three successive banzai charges. their shotguns, creating what one Japanese survivor called wallsof metal rain.

Lieutenant Tadashi Suzuki wrote home, “The Americans have a demon weapon. It speaks with thunder and throws metal rain that cuts down entire squads. Still, Japanese high command dismissed these reports. General Hayakutaki’s staff concluded the shotgun was a terror weapon used by Americans who lack the courage for proper combat and they issued orders emphasizing that spiritual strength and speed will overcome any mechanical device.

The DA lessons of Guadal Canal went unheeded. Japanese military culture couldn’t yet accept that their mastery of close combat was being negated by American firepower. that education would come later, written in blood across a dozen more islands. By mid 1943, the evidence was becoming impossible to ignore. On New Georgia, Captain Ichiro Yamamoto’s company, 187 veteran soldiers, launched a textbook night infiltration against Marine positions near Munda Airfield on July 17th.

They moved in perfect silence. Bayonets blackened, confident in 3 years of combat experience. By dawn, 163 were dead or dying. The Marine defenders reported firing over 2,000 shotgun shells in less than 20 minutes. Dr. Hiroshi Tanaka, chief surgeon at the 17th Field Hospital, documented what he called the shotgun syndrome in his medical reports.

Traditional battlefield surgery prepared us for single projectile wounds. These American weapons create multiple wound channels, nine, sometimes 12 separate entries. The trauma is catastrophic. Men hit at 30 m show damage consistent with artillery strikes. The statistics were stark. Japanese casualty analysis from the Central Solomon’s campaign showed banzai charges against riflear armed Americans succeeded 34% of the time with 40 60% casualties.

Against shotgun equipped units, success rate dropped to zero with casualties exceeding 85%. Colonel Teo Ido reviewing these numbers wrote in his private journal, “Our night attacks have become suicide. The Americans have learned to make the darkness their ally.” At Cape Tokuna Buganville, the full horror became clear. On November 7th, 1943, Major Chagaru’s battalion, 850 men trained specifically in night infiltration tactics attempted to overrun Marine positions held by the Third Raider Battalion.

The Marines had positioned themselves in interlocking fields of fire, shotguns loaded with buckshot. Sergeant Yukio Mishima survived by playing dead among his shredded squadmates, and his testimony to military investigators was damning. We could not close the distance. At 40 m, the thunder began. Men fell in groups, not singly.

The jungle itself seemed to explode with metal. I saw Lieutenant Hagawa take a full blast. His chest opened like a flower. There was no glory, no combat, only execution. The 17th Army’s intelligence section compiled a secret report analyzing the Cape Tokina disaster. 89% of casualties came from shotgun wounds.

Average engagement range, 25 m. Average time from first contact to unit destruction, 4 minutes. The report’s conclusion was revolutionary for Japanese military thinking. Enemy automatic weapons and shotguns have negated our advantages in night combat and spiritual strength. Lieutenant Colonel Susimu Nishida, one of the few senior officers to survive Cape Turokina, wrote the words that would have been heresy months earlier.

We have been teaching our men to bring swords to a thunderstorm. The Americans fight without Bushidto, but they fight to win. We must abandon our cherished tactics or face annihilation. The revelation was spreading through the ranks like wildfire. The thundersticks weren’t cowardly. They were devastatingly practical, and practicality, it seemed, trumped warrior spirit every time.

The weapon that shattered Japanese close combat doctrine was deceptively simple. The Winchester Model 97, designed in 1897 for hunting water fowl, became a jungle warfare revolution. Its specifications told the story. 12 gauge bore, six round magazine, and most crucially, the ability to slam fire. Holding the trigger down while pumping allowed all six rounds to fire in under two seconds.

Marines called it the trench broom, and in the dense Pacific jungles, it swept clean. The mathematics of destruction were simple. Each 12- gauge shell contained nine pellets of 00 buckshot. Each pellet 33 in in diameter, essentially nine separate bullets. At 10 yards, the pattern spread to 12 in. At 25 yards, 30 in.

At 40 yards, nearly 4 ft. A charging Japanese soldier at typical jungle engagement range faced not one projectile, but nine, spread across an area impossible to dodge. The Model 12, introduced to Marine units in 1943, refined the concept further. Smoother action, better balance, and tighter manufacturing tolerances meant even faster cycling.

Marine Gunnery Sergeant Robert Holmes, who trained raiders in shotgun tactics, explained, “In jungle visibility of 10 to 15 yards, that Arasaka rifle might as well be a club. But my shotgun, it’s throwing a baseball-sized pattern of death everyhalf second.” Ammunition selection proved crucial. While buckshot devastated at close range, Marines also carried brass-cased shells loaded with 21 pellets of dem shot for ultra close work and rifled slugs that could punch through light cover at 75 yards.

The versatility meant one weapon system could handle any range the jungle allowed. Production statistics revealed American industrial logic. While Japanese soldiers spent years perfecting bayonet techniques, American factories produced 1.2 2 million military shotguns. Between 1941 and 1945, the Marine Corps alone received 61,000 Model 97s and 35,000 Model 12s, and ammunition production exceeded 100 million shells with priority shipment to Pacific units.

The tactical mathematics were irrefutable. A Japanese Type 38 rifle, supremely accurate at 500 yd, fired one 6.5 mm bullet every 3 seconds in trained hands. In jungle combat at 15 yards, that precision was worthless. A marine with a shotgun could put 54 projectiles downrange in the time a Japanese soldier fired two aimed shots. At night infiltration ranges, it wasn’t a contest. It was mechanical slaughter.

Colonel Merritt Edson, whose raiders had proven the shotguns worth on Guadal Canal, summarized the equation. The Japanese trained for years to be superior at close combat. We gave an 18-year-old farm boy from Iowa a shotgun and three days of training in the jungle. That boy wins every time. That’s not dishonor.

That’s American pragmatism. Lieutenant Kenji Ishikawa’s diary survived the war discovered in a cave on Paleu. His entries traced a psychological journey shared by thousands. June 1943. The Americans rely on their machines because they lack warrior spirit. When we close to sword range, they will break as they always do. September 1943.

Sato’s company was destroyed last night. The survivors speak of thunder weapons that kill five men with one shot. This cannot be true. November 1943. I have seen the thunder guns. They do not kill five men. They destroy them. There is no honor in this death. No chance for glory. The thunder guns have broken our spirit.

Marine Sergeant Dale Miller from Ohio wrote different letters home as the war progressed. August 1942. Mom, we have these shotguns just like dad uses for ducks. They work real good in the jungle. By December 1943, his tone had changed. I shot a officer last night. He was younger than Tommy. The buckshot nearly cut him in half.

I know they’re trying to kill us, but God, what these guns do to a man. Sometimes I wake up seeing their faces. Tell dad I understand now why he never talked about the trenches. Corporal Hiroshi Yamada survived a shotgun ambush on New Georgia. One of 11 survivors from a company of 150. Interviewed in 1987.

He still couldn’t speak of it without trembling. I was in the third rank when the thunder started. The men in front of me just came apart. I felt wetness on my face and it was blood and tissue from my sergeant. I fell and played dead for 6 hours lying under bodies. Even now I cannot hear thunder without returning to that night.

The war ended for me there, though I fought two more years. My soul died in that jungle. The most profound story emerged from an unlikely reunion in 1975. Former Marine Jim Patterson attended a veterans conference in Hawaii where he met Teeshi Ogawa who had led a banzai charge against Patterson’s position on Saipan.

Through a translator, Ogawa approached Patterson with tears in his eyes. You were the one with the shotgun at Hill 27. When Patterson nodded, Ogawa bowed deeply. You killed my entire squad in seconds. I hated you for 30 years, but now I thank you. Your thunder gun ended our madness quickly. My friends died instantly. No suffering.

You saved us from our own foolishness. Patterson’s daughter, interviewed in 2010, remembered her father’s response. Dad just stood there crying. these two old men who’ tried to kill each other, hugging and sobbing. Dad never talked about the war, but that night he told me everything. He said the shotgun was both the best and worst thing that happened to him.

It kept him alive, but gave him nightmares for life. He and Mr. Aawa wrote letters until dad died. Two men bonded by understanding that war makes everyone a victim. These personal accounts revealed the deeper truth beyond tactics and technology. The shotgun’s psychological impact lasted lifetimes, transforming warriors into haunted men, creating bonds between enemies who understood what others couldn’t.

That efficiency in killing carried its own terrible burden. The transformation became official on Pleu. In September 1944, the first marine division expected the familiar pattern. fierce initial resistance followed by suicidal banzai charges that while deadly ultimately hastened Japanese defeat. Instead, they found something unprecedented.

Japanese forces that refused to leave their positions, refused to charge, refused to die gloriously. Colonel Kuno Nakagawa, commanding Pleu’sdefenders, had received new orders from General Sedai Inway that would have been unthinkable a year earlier. Spiritual strength alone cannot overcome American firepower.

Each soldier will fight from prepared positions. There will be no banzai charges. Make the Americans come to you. The specific tactical manual revision intercepted by American intelligence stated bluntly. Night attacks against enemies equipped with automatic weapons and shotguns result only in useless death. The psychological shift was even more dramatic than the tactical one.

Captain Toshio Yamaguchi’s recovered notes described what he called the shotgun sickness spreading through his men. Private Sato refuses night patrol duty. When pressed, he begins shaking and speaking of the thunder guns. This cowardice spreads like disease. Yesterday, an entire squad claimed illness rather than conduct infiltration training.

They are not sick in body, but in spirit. American intelligence officer Major Frank Stevens noted the change in intercepted communications. 6 months ago, Japanese radio traffic was all about honor and spiritual superiority. Now we’re intercepting desperate requests for counter shotgun tactics and methods to engage Americans beyond thunder gun range.

They’re asking Tokyo for weapons that don’t exist. The Marines on Paleu faced a horrifying new reality without banzai charges to break them. Japanese forces held positions until blasted out by flamethrowers and demolitions. The battle that should have taken days stretched to months. Ironically, by abandoning their close combat doctrine, the Japanese had found a deadlier approach.

Lieutenant Colonel Lewis Chesty Puller observed. We trained these boys to repel banzai charges with shotguns and automatic weapons. Now the jabs won’t come out to be killed. They’ve learned our lessons too well. Marine casualties on Paleleu exceeded those on any previous Pacific battle precisely because the Japanese no longer offered themselves to American firepower.

The abandoned banzai doctrine represented more than tactical evolution. It was the death of Japan’s warrior mythology. A captured Japanese training document from October 1944 summarized the transformation. The age of the sword has ended. Survival, not glory, is victory. Avoid American shotguns at all costs. The samurai spirit hadn’t been defeated by superior philosophy or greater courage.

It had been demolished by buckshot and pragmatism, forcing a warrior culture to confront the reality that their cherished beliefs were literally killing them. The shotgun revelation rippled through the Japanese military like a stone dropped in still water. By December 1944, the Imperial Army’s training manual had undergone its most radical revision in history, where once it devoted 40 pages to the spirit of the bayonet, the new edition contained a single paragraph ending with close combat against American forces equipped

with automatic weapons should be avoided, except under the most favorable circumstances. The transformation was documented in reports from across the Pacific. On bypassed Rabal, Lieutenant General Hitoshi Imamura wrote to Tokyo, “My men have lost faith in our fundamental tactics.

They speak of American thunder weapons with the fear once reserved for evil spirits. The Americans fight without honor, but with terrible efficiency. We trained our men to die gloriously. The Americans trained theirs to kill efficiently. We were fools.” The psychological impact proved devastating. Major Yoshio Nisha, commanding a garrison in the marshals, reported desertion rates climbing 400%.

Men disappear into the jungle rather than face night combat. They say death by starvation is preferable to the thunder guns. This is not the Imperial Army I knew. These are broken men afraid of the dark we once owned. Home island defense planning reflected the new reality. The original operation Ketugo called for massive coastal bonsai charges to drive invaders into the sea, but revised plans from January 1945 abandoned this entirely.

General Kuricha Anami’s planning staff wrote, “Costal defenders will withdraw inland immediately. No close combat engagements. Artillery and mortars will engage American forces at maximum range. The samurai sword had been replaced by the desperate hope of making invasion too costly through distance and attrition. Training camps in Japan struggled to adapt.

Sergeant instructor Masau Watanabe recorded, “How do I train men for combat I no longer believe in?” “Yesterday, I demonstrated classical bayonet techniques.” A recruit asked, “What use is this against American shotguns?” I had no answer. “We are training for the last war while the enemy prepares for the next.” The broader implications were staggering.

Colonel Tekashi Sakai in a report marked secret not for distribution wrote what many thought but dared not say. We mistook American preference for firepower as weakness. We called them soft for valuing their soldiers lives.But this weakness has proved superior to our strength. They fight without bushidto because they fight to win not to die gloriously.

We have been defeated not just tactically but philosophically. By early 1945, the Japanese military had effectively abandoned every principle that defined its warrior culture. The shotgun hadn’t just killed Japanese soldiers. It had killed the mythology that sent them to their deaths. The thunder in the jungle had silenced the samurai spirit forever.

The ultimate irony emerged in 1954 when the newly formed Japanese Self-Defense Force issued its first equipment requirements. At the top of the close combat weapons list stood automatic shotguns for jungle and urban warfare. The same nation that had once condemned shotguns as dishonorable now recognized them as essential.

Colonel Manoru Jenda, who had planned Pearl Harbor, supervised the procurement, stating simply, “We learned our lessons in blood. Only fools ignore such education.” Postwar military studies were brutally honest. The 1952 Pacific War tactical analysis commissioned by the Japanese government devoted an entire chapter to the shotgun factor, concluding, “American close combat superiority stemmed not from courage, but from practical weapon selection.

The shotgun represented perfect adaptation to Pacific combat conditions. Our refusal to acknowledge this reality caused approximately 70,000 unnecessary casualties. Veterans Association struggled with the trauma. At the 1960 Pacific War Veterans Conference in Tokyo, survivor Tadashi Kamura spoke for many.

We cannot forget the thunder guns. Young men today ask why we feared American weapons. How do you explain facing impossible firepower? How do you describe watching your entire squad disappear in seconds? We were not cowards. We were men asked to fight the future with the past. Dr. for Saburro Hayashi, Japan’s leading military historian, published his definitive analysis in 1965.

The shotgun debate represents our entire wartime failure. We prioritize spiritual factors over practical reality. We called pragmatism cowardice and paid for this arrogance with our best men’s lives. The Americans didn’t fight without honor. They simply defined honor as bringing their soldiers home alive. The transformation reached its apex in 1967 when Mioku Corporation, working with JSDF specifications, developed the model 2800 combat shotgun, a weapon designed to exceed American models in rate of fire and ammunition capacity.

The marketing materials read like redemption. Superior close combat firepower for modern warfare. Former Lieutenant General Toshio Tamogami, interviewed in 1995, provided the final verdict. My generation died believing in sword against shotgun. We called Americans weak for choosing firepower over spirit.

But they went home to their families while we became cherry blossoms, falling uselessly. If admitting this truth dishonors our dead, then perhaps honor itself needs redefinition. By the 1970s, Japanese military doctrine had completely reversed. Training manuals emphasized firepower, technology, and force preservation. The warrior spirit remained, but tempered by pragmatism, and the nation that had mocked American cowardice now trained its forces with the simple principle.

Victory through superior firepower. The Thunder Guns had won more than battles, and they had transformed an entire military culture’s understanding of modern warfare. The Japanese encounter with American shotgun stands as history’s darkest lesson in the fatal cost of cultural arrogance. What began as contempt for cowardly weapons became a complete philosophical reversal written in the blood of young men who died for outdated ideals.

The shotgun served as a brutal metaphor for the broader American approach to warfare. Pragmatic, industrial, and utterly without romance. Today’s military theorists study the Pacific shotgun encounters as a masterclass in asymmetric adaptation. In Iraq and Afghanistan, American forces again turned to shotguns for urban combat, proving that some lessons transcend generations.

The Benelli M4, standard issue for breaching operations, carries forward the legacy of those Winchester Model 97s that shattered Japanese doctrine, reminding strategists that close quarters combat still belongs to whoever brings the most efficient killing tool, not the most honored tradition. The psychological dimension remains equally relevant.

Modern militaries understand that breaking an enemy’s cultural assumptions can be more devastating than breaking their bodies. And when core beliefs prove fatally wrong, entire armies can collapse from within. The Japanese soldiers who developed shotgun phobia weren’t cowards. They were rational men recognizing that their training had prepared them for suicide, not victory.

But the deepest lesson lies in the human cost of institutional rigidity. How many young Japanese men died because their leaders couldn’t admit that spiritualstrength meant nothing against buckshot? How many families lost sons to the gap between mythology and reality? Every military culture faces this choice.

Evolve or watch your children die for yesterday’s doctrine. The thunder guns fell silent in 1945, but their echo remains. In war, there is no honor in sending men to die with obsolete tactics. The greatest courage lies in adaptation. The deepest wisdom in protecting your people with every advantage available.

And those who call pragmatism cowardice have never heard the sound of buckshot in the jungle.

News

Praying with Impact – Dr. Charles Stanley

Praying with Impact – Dr. Charles Stanley Dr. Charles Stanley, M.D.: In Touch, the teaching ministry of Dr. Charles Stanley….

John Wayne Saw A Wheelchair At His Movie Premiere—What He Did Next Changed A Life Forever

John Wayne Saw A Wheelchair At His Movie Premiere—What He Did Next Changed A Life Forever March 1970, John Wayne…

Why George Marshall Said NO to a 200-Division Army — WWII’s Boldest Gamble

Why George Marshall Said NO to a 200-Division Army — WWII’s Boldest Gamble December 1941, the United States had just…

Dying Boy Was DENIED His Last Wish — Clint Eastwood Shocks The World With THIS Move!

Dying Boy Was DENIED His Last Wish — Clint Eastwood Shocks The World With THIS Move! Liam stared at the…

The Football Coach Who Led 225 Men Up A Suic*de Cliff On D-Day

The Football Coach Who Led 225 Men Up A Suic*de Cliff On D-Day Welcome to History USA, where we uncover…

John Wayne Crashed This Sailor’s Wedding—What He Left Them Changed Everything

John Wayne Crashed This Sailor’s Wedding—What He Left Them Changed Everything June 1954. A young Navy sailor marries his high…

End of content

No more pages to load