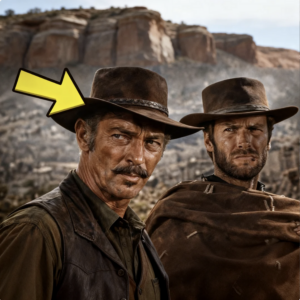

Lee Van Cleef Finally Tells the Truth About Clint Eastwood

Lee Vancliffe finally tells the truth about Clint Eastwood. Lee Van Clee was born Clarence Leroy Van Clee Jr. on January 9th, 1925 in Somerville, New Jersey. Van Clee grew up during the hardships of the Great Depression. From an early age, he displayed a strong sense of independence, self-discipline, and determination, traits that would later define both his personal life and his screen persona.

He served in the United States Navy during World War II, an experience that instilled in him a lifelong respect for structure, resilience, and duty. After the war, Van Clee turned toward acting, studying theater, and honing his craft with the seriousness of someone who understood that success would not come easily. Van Clee made his film debut in High Noon 1952, a landmark western that introduced audiences to his striking face and quiet intensity.

Though his role was small and largely silent, it was impossible to overlook him. Hollywood quickly took notice, but not always in ways that benefited him. His unconventional looks, so iconic today, initially confined him to roles as outlaws, henchmen, and secondary villains. Throughout the 1950s, he appeared in dozens of westerns and television series, including the Lone Ranger, Gunsmoke, and Havegun Will Travel.

While these roles rarely placed him at the center of the story, they showcased his ability to convey menace and intelligence with minimal dialogue using posture, expression, and timing rather than theatrics. Despite steady work, Van Clee’s early career was defined more by persistence than by stardom. A serious car accident in 1958 temporarily halted his momentum and for a time it seemed as though Hollywood might never fully recognize his potential.

Yet this setback became a turning point rather than an ending. When opportunities in American cinema began to wne, Van Clee found new life overseas, particularly in Italy, where filmmakers were redefining the western genre with darker themes, moral ambiguity, and oporadic intensity. His collaboration with director Sergio Leone proved transformative.

Cast as Colonel Douglas Mortimer in For a Few Dollars More, 1965, Van Clee finally emerged as a leading man. His performance was a revelation, calm, calculating, and deeply human beneath the steely exterior. Unlike the one-dimensional villains of his early career, Mortimer was complex, driven by personal loss and a strict moral code.

The role allowed Van Clee to demonstrate emotional depth and commanding authority, earning him international acclaim and cementing his status as a star. Van Clee’s success continued with films such as The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly, 1966, Day of Anger, 1967, and The Big Gundown, 1966. In these films, he often played men who operated in the gray areas between justice and revenge, characters shaped by experience, loss, and survival rather than simple notions of good and evil.

His performances resonated deeply with audiences because they felt authentic and lived in. He did not overplay violence or heroism. Instead, he conveyed strength through restraint, making his characters all the more compelling. What set Lee Van Clee apart was not just his appearance or his association with a groundbreaking genre, but his professionalism and integrity.

Known for his quiet demeanor offscreen, he approached acting as a craft rather than a vehicle for fame. Colleagues frequently described him as disciplined, courteous, and deeply serious about his work. He never forgot the years of struggle that preceded his success, and he carried himself with humility even at the height of his popularity.

In later years, Van Clee returned to American Productions, appearing in films such as Escape from New York, 1981, where he played the authoritative and morally ambiguous police commissioner Bob Hawk. Once again, his presence elevated the material, lending credibility and gravitas to the role. Even as he aged, Van Clee continued working steadily, embracing roles that suited his experience and commanding screen persona.

Lee Van Clee’s personal life, though often kept in the shadow of his formidable screen persona, reflected a journey marked by devotion, transition, and eventual stability. Much like the rugged, morally complex characters he portrayed so memorably throughout his career, Van Clee married his first wife, Paty Ruth Kaye, in 1943 during the tumultuous years of World War II.

At the time, Van Clee was a young man still finding his place in the world, long before his angular features and piercing gaze would make him an icon of western cinema. Their marriage coincided with his service in the United States Navy, where he endured both the discipline of military life and the physical challenges that followed an injury, experiences that would later shape his stoic screen presence.

Together, Van Clee and Kaye built a family, welcoming three children over the course of their marriage. These years were marked by responsibility and sacrifice as Van Cleestruggled through the early stages of his acting career, taking small, often uncredited roles and working various jobs to support his growing family. Despite their shared history and the bonds of parenthood, the pressures of ambition, financial uncertainty, and the demands of an unpredictable profession gradually took their toll.

After 15 years together, the couple divorced in 1958, closing a significant chapter in Van Clee’s life, but leaving behind the enduring legacy of their children. In 1960, as his career slowly began to regain momentum after a devastating horseback riding accident temporarily sidelined him, Van Clee married Joan Marjgery Dra.

This second marriage unfolded during a transitional period both personally and professionally. Van Clee was no longer the struggling newcomer. Yet he had not fully achieved the international recognition that would later define his legacy. Dra stood by him during years of rebuilding. Years in which he worked steadily in television and film, often portraying villains or morally ambiguous figures that capitalized on his sharp features and commanding presence.

While the marriage lasted over a decade, it ultimately faced challenges similar to those of his first. Long separations, the consuming nature of his work, and the difficulty of maintaining domestic harmony amid a demanding career. Their relationship ended in divorce in 1974, a period that coincided with Van Clee’s rising fame in Europe following his legendary collaborations with Sergio Leone and other Italian filmmakers.

Finally, in 1976, Van Clee found lasting companionship with Barbara Havalone, whom he married at a time when his career had reached a new level of respect and recognition. By then, he was no longer merely a supporting actor or cinematic villain. He was a star in his own right, celebrated worldwide for his performances in spaghetti westerns and action films.

His marriage to Havalone brought a sense of stability and comfort that had eluded him in earlier years. Their relationship endured through the later stages of his career, as well as through his declining health. Barbara remained by his side until the end of his life, offering companionship and support as he faced illness with the same quiet toughness that defined his screen image.

When Lee Van Clee passed away in 1989, Barbara Havalone survived him, standing as a testament to the enduring bond they shared during his final years. For decades, Lee Van Clee was known as the man with the unforgettable face, sharp features, icy eyes, and a presence that could dominate the screen without a single word.

Yet, behind the image of the perfect cinematic villain was a thoughtful, observant actor who understood the machinery of Hollywood better than most. Late in life, Van Clee finally spoke candidly about the man most closely associated with his legacy, Clint Eastwood, and his words were marked not by bitterness, but by honesty and hard-earned clarity.

I think people like to imagine that Clint and I were rivals, Van Clee once said. But the truth is simpler than that. We were two men doing our jobs, walking very different paths that happened to cross at the right moment. Van Clee acknowledged that Eastwood arrived in the Italian westerns with momentum, youth, and an instinctive understanding of how little he needed to do on screen.

Clint knew the power of stillness, he explained. He didn’t rush. He let the camera come to him. That’s something you can’t teach. Van Clee admitted that when he first worked alongside Eastwood in For a Few Dollar More, he recognized immediately that Eastwood was becoming something rare. You could feel it,” he said. The crew felt it. The audience felt it.

Clint wasn’t just playing a gunslinger. He was becoming a symbol. Yet Van Clee was careful to clarify that Eastwood’s success was not accidental. He worked for that image. He protected it. He understood that silence, restraint, and confidence were his greatest weapons. While Eastwood ascended rapidly to stardom, Van Clee’s career followed a more winding road.

He spoke openly about this contrast without resentment. Clint fit the American myth perfectly, he reflected, tall, calm, heroic in a modern way. I didn’t. My face told different stories. I was danger. I was the man you didn’t trust. And that was fine. I learned to own it. Van Clee believed that his own resurgence in Italian cinema proved there was more than one way to succeed.

“I didn’t need to be the hero,” he said. “I needed to be unforgettable.” Van Clee also rejected the idea that Eastwood overshadowed him. “If anything, Clint helped define me.” He said, “Without that contrast, the clean hero and the morally gray hunter for a few dollars more wouldn’t have worked the same way.” He praised Eastwood’s professionalism, noting that there was never hostility between them. Clint showed up prepared.

He respected the work. That’s all an actor can ask of another actor. Perhaps most revealing were Van Cleiff’sthoughts on how history remembered them. Clint became a legend in front of the camera and then behind it. He said, “I became a legend in a different way. People remember my eyes, my walk, my silence.

That’s a kind of immortality, too.” He believed that time ultimately placed every artist where they belonged. Hollywood is loud when you’re young, he mused. But when the noise fades, only the truth remains. In the end, Lee Vancle’s words about Clint Eastwood were not confessional or confrontational. They were balanced and deeply human. Clint Eastwood earned what he became, Van Clee concluded.

And I earned what I became. We were never meant to be the same man. We were meant to stand across from each other, framed in dust and sunlight, and let the audience decide what kind of legend they needed. Through those reflections, Van Clee finally told the truth, not just about Eastwood, but about himself, and about the quiet dignity of carving one’s own place in cinematic history.

Despite a body increasingly burdened by illness, Lee Van Clee never surrendered his devotion to the screen. From the 1970s onward, he lived with serious heart disease, a condition that would have persuaded many to retreat into quiet retirement. Instead, Van Clee pressed on with remarkable resolve. By the 1980s, a pacemaker had been implanted to regulate his failing heart, a constant mechanical reminder of his mortality, but also a silent partner that allowed him to keep doing what he loved most.

Even as his health declined, his presence remained commanding, his performances infused with the same razor-sharp intensity and magnetic menace that had defined his career. To the very end, Van Clee was a working actor, refusing to let physical frailty eclipse the fierce spirit that had carried him from obscure bit parts to international stardom.

On December 16th, 1989, that indomitable journey came to a close. Van Clee collapsed from a heart attack in his home in Oxnard, California, a quiet and private setting that contrasted sharply with the larger than-l life figures he so often portrayed on screen. Throat cancer was later listed as a secondary cause of death, underscoring the extent to which his final years were marked by profound physical challenges.

Yet, even in death, the narrative of Lee Van Clee is not one of defeat, but of endurance. of an artist who continued to create, perform, and captivate audiences long after his body began to betray him. He was laid to rest at Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in the Hollywood Hills, a resting place befitting a figure so deeply woven into the fabric of cinematic history.

Etched into his grave marker are the words, “Best of the bad.” A simple but powerful epitap that perfectly captures his legacy. It is a tribute not only to his unforgettable portrayals of villains, outlaws, and anti-heroes, but also to the artistry and charisma he brought to roles that might otherwise have been one-dimensional.

Lee Van Clee did not merely play villains. He elevated them, giving them depth, intelligence, and a chilling elegance that audiences could never forget. In life and in death, he remains a towering figure of classic cinema. Resilient, uncompromising, and forever the best of the bad.

News

John Wayne Met A Real IWO JIMA Marine At His Movie Premiere—The Salute Changed Everything

John Wayne Met A Real IWO JIMA Marine At His Movie Premiere—The Salute Changed Everything November 1949. A man in…

Arab Billionaire Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Don’t Belong Here’ — Instantly Regrets It!

Arab Billionaire Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Don’t Belong Here’ — Instantly Regrets It! When the doors of Leardam, one of…

John Ford Never Forgot the Way Lee Marvin Looked at John Wayne on The Hawaiian Beach After the Punch

John Ford Never Forgot the Way Lee Marvin Looked at John Wayne on The Hawaiian Beach After the Punch John…

Why Delta Force HATES Training with the SAS

Why Delta Force HATES Training with the SAS America’s most elite soldiers learned everything from the British SAS. Yet every…

Bikers Thought He Was Just Another Old Man — Then Realized It Was Ozzy Osbourne…

Bikers Thought He Was Just Another Old Man — Then Realized It Was Ozzy Osbourne… Picture this. A lonely gas…

WHAT JAPAN’S LEADERS ADMITTED When They Realized America Couldn’t Be Invaded

WHAT JAPAN’S LEADERS ADMITTED When They Realized America Couldn’t Be Invaded In the stunned aftermath of Pearl Harbor as Japanese…

End of content

No more pages to load