America Had No Lightweight Field Rations in 1941 — So Ancel Keys Raided A Grocery Store

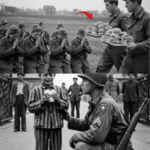

The year is 1941. You are strapped into the jump seat of a C-47 sky train, screaming through the air at 150 mph. The vibration rattles your teeth. The smell of high octane aviation fuel burns your nose. Look around you. You are sitting next to the absolute elite of the United States military, the paratroopers.

These men are designed for one thing: vertical envelopment. speed, surprise, and violence of action. But there is a problem, a heavy, loud, metallic problem. Look at their gear. These men are beasts of burden. They are carrying nearly 100 pounds of equipment, ammunition, explosives, radios, and shovels.

But the thing that is actually going to get them killed isn’t the weight of the lead. It’s the weight of the lunch. Every time they move, they rattle. A distinct metallic clanking that sounds less like a ninja in the night and more like a dairy cow wandering through a barn. That sound is the sea ration. Heavy wet stew sealed inside solid steel cans.

To an elite soldier trying to sneak behind enemy lines, a backpack full of steel cans is a death sentence. It’s loud, it’s heavy, and it requires a literal key to open. If you lose the key in the mud, you starve. This was the logistical nightmare facing the Allied powers at the dawn of the Second World War. The rule book of warfare had changed.

For centuries, armies moved at the speed of their slowest wagon. You marched, you set up camp, you waited for the field kitchens to roll up, and you ate a hot stew ladled out by a cook. That worked fine for the static trenches of World War I. But this was the era of Blitzkrieg, the Lightning War. The Germans were moving faster than logic should allow.

Tanks were breaking through lines and driving for days without stopping. If the US Army wanted to liberate Europe, they couldn’t be tethered to a slowmoving soup kitchen. They needed their soldiers to be self-sufficient, mobile, and lethal. They needed to cut the umbilical cord. The quartermaster corps, the guys in charge of the supplies, knew this, and their solution was frankly insulting.

They gave the soldiers the dration. This was the iron ration. It was a 4 oz bar of chocolate, but this wasn’t a treat. The military specifications for this bar explicitly stated that it had to be heatresistant up to 120°. And crucially, it had to taste a little better than a boiled potato.

They intentionally made it taste terrible so soldiers wouldn’t eat it unless they were literally dying of starvation. It was a rockhard brick of bitter chocolate and oat flour that was so dense soldiers with bad teeth couldn’t even bite into it. They had to shave slices off with a combat knife like they were whittling wood.

So here is the crisis. The United States has the industrial might to build thousands of Sherman tanks. They have the manpower to storm the beaches. They have the sheer volume of high explosives to level mountains. But they are facing a total logistical collapse before the first boat even hits the sand.

You have the best trained soldiers in history, but you are weighing them down with steel cans that give away their position. Or you are handing them caloric bricks that are physically painful to eat. You cannot invade a continent on an empty stomach, and you cannot win a war of movement if your army is anchored by the weight of its own food.

The US military had a billion dollars to spend on weapons, but they didn’t have a single edible meal that could fit in a paratrooper’s pocket. They needed a miracle. They needed 3,000 calories that weighed nothing, tasted good enough to boost morale, and could survive a drop from 10,000 ft. The generals thought the answer was bigger trucks.

They were wrong. The answer was hiding in a grocery store in Minneapolis. Enter Dr. Anel Keys. If you were casting a movie about the man who would save the US army from starving, you wouldn’t cast Anel Keys. He wasn’t a grizzled general chomping on a cigar. And he wasn’t a master chef. He was a physiologist from the University of Minnesota.

To the old guard at the Quartermaster Corps, men who believed an army marched on steak, potatoes, and heavy stews, Keys was just another egghehead academic in a tweed jacket. When Keys approached the War Department with the idea of a lightweight, high calorie pocket meal, the brass practically rolled their eyes. The prevailing military wisdom of 1941 was that soldiers needed rugged food.

They viewed lightweight rations as snacks, not fuel for warriors. They were obsessed with bulk, believing that physical weight equaled nutritional value. Keys knew that was nonsense. He understood the physics of the human body. He knew that a paratrooper dropping into Normandy didn’t need the sensation of a full stomach.

He needed raw, burnable energy, and he needed it to weigh less than a hand grenade. So, while the military bureaucracy was busy forming committees to discuss canning procedures, Dr. Keys left his office and drove to a local grocery store inMinneapolis. This is the moment of engineering brilliance. It didn’t happen in a sterile government lab.

It happened in the cracker aisle. Keys wasn’t trying to invent a new food. He was trying to engineer a caloric delivery system. He walked the aisles grabbing items that met three specific criteria. They had to be cheap. They had to be shelf stable. And they had to be dense with energy. He grabbed hard biscuits, dry sausages, fruit bars, chocolate, and chewing gum.

He took this basket of groceries back to the lab and created a prototype meal that cost a few pennies, but solved a million-doll logistical problem. He called it the Kration, named naturally after himself. Here is the technical breakdown of why this was a revolution. It comes down to a simple A versus B comparison in materials engineering.

The old way, the C ration, relied on the technology of the 19th century. The steel can. Steel is heavy. Steel is rigid. If you pack 3 days of food in steel cans, you are adding nearly 10 lb of dead weight to a solders’s pack. That is 10 lb of ammunition he can’t carry. Furthermore, steel has a packing inefficiency.

Round cans don’t stack perfectly. They leave gaps of wasted space in every crate. Keys new way was a triumph of packaging engineering. He ditched the metal entirely. He utilized a threebox system. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner packaged in rectangular cardboard boxes. But cardboard dissolves in the rain, right? Not the way Keys did it.

He had the boxes heavily dipped in wax. This created a hermetic seal that was waterproof, gasp proof, and arguably most importantly, pestproof. You could drop a Kration in a muddy swamp in the Pacific, leave it there for a week, fish it out, and the biscuits inside would be bone dry.

Inside these wax bricks was 3,000 calories of pure fuel, processed cheese, meat hash, biscuits, and fruit bars. But the real genius was in the soft engineering, the psychology. Keys included instant coffee. The generals scoffed, but Keys knew that a hit of caffeine in a freezing foxhole could act as a force multiplier for alertness.

And then there was the gum. The brass laughed at the idea of including candy in a combat ration. Keys argued that the gum wasn’t candy. It was a toothbrush for the field, increasing dental hygiene when brushes weren’t available, and a psychological stress reliever. The rhythmic act of chewing lowers cortisol levels.

He wasn’t just feeding the machine. He was maintaining the operator. The kration weighed mere ounces. It fit in a pocket. It required no can opener, no fire, and no preparation. Ancel Keys had just turned the American soldier into a self-sustaining unit of war. Now he just had to prove it worked. The true test of Dr.

Keys’s grocery store experiment wasn’t in a laboratory in Minnesota. It was in the hedge of Normandy, June 1944. Picture the chaos. The 101st and 82nd Airborne have dropped behind enemy lines. It is a complete disaster. Units are scattered, commanders are missing, and the gliders carrying heavy equipment have been torn apart by German anti-aircraft fire.

The supply trucks are miles away on the beach, stuck in traffic or burning in the sand. The field kitchens non-existent. By all traditional military logic, these men are combat ineffective. They are cut off, surrounded, and exhausted. This is where the German logistical model predicted the Americans would stall. The Germans, for all their technological terror, were still largely relying on horsedrawn supply wagons and centralized field kitchens.

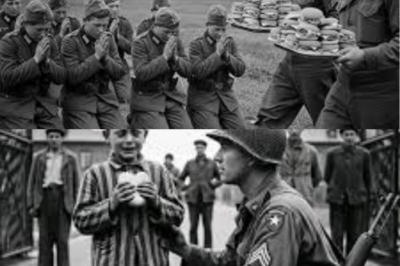

If you bombed the kitchen, the unit didn’t eat. If the unit didn’t eat, the unit didn’t fight. But deep in a foxhole near Saintmeir Agles, a shivering American paratrooper does something that changes the calculus of the battle. He doesn’t radio for a supply drop. He reaches into his jump jacket and pulls out a wax sealed cardboard brick. He cracks the seal.

The smell of pork lunchon meat wafts out. It’s salty, processed, and to a starving man, it smells like victory. He stacks the meat on a dense cracker. He chews the gum to calm his nerves while mortar shells walk across the field next to him. He uses a packet of citric acid powder and rain water to make lemonade in a tin cup.

In 5 minutes, he has consumed 1,000 calories. The energy kick hits. The glucose floods his system. He stands up, checks his rifle, and moves out. This was the vindication. Multiply that one soldier by 20,000. The Allied paratroopers didn’t need to wait for the supply train. They carried their supply train in their pockets.

They were able to sprint, fight, and survive for 3 days of intense combat without a single truck reaching them. The snack that the generals mocked was the fuel that kept the most mobile army in history moving forward. And once the concept was proven, the American industrial machine kicked into a gear that the Axis powers simply couldn’t comprehend.

This is the scale. The War Department, realizing they had a winner, turned the Krationinto one of the most mass-roduced items of the 20th century. Companies that used to make cereal or candy were converted overnight into K-ration factories. At the peak of production, the United States wasn’t just building tanks and planes.

They were producing over 100 million rations a year. It was a logistical tsunami. While German soldiers on the Eastern Front were freezing, waiting for a horsedrawn cart to bring them a loaf of stale bread, American GIs in the Pacific, in Italy, and in France were tearing open fresh waterproof boxes of energy. The Kration became the currency of liberation.

It was ubiquitous. You could find empty kration boxes littering the jungles of Guadal Canal and the streets of Bastonia. It turned the complex problem of feeding an army into a simple, disposable afterthought. The genius wasn’t just that it fed the soldiers. It was that it freed them. It liberated the American soldier from the tether of the supply line, allowing General Patton to race across France at a speed that broke the back of the Vermacht.

The egghehead from Minnesota hadn’t just built a better lunch. He had engineered the fuel for the Blitzkrieg that ended the Nazis. To be clear, while the kration was an engineering marvel, it wasn’t a culinary masterpiece. And this brings us to the complicated legacy of Anel Keyy’s invention. As the war dragged on from weeks into months, a new problem emerged. Menu fatigue.

Imagine eating the same processed meat, the same dry biscuit, and the same fruit bar for breakfast, lunch, and dinner every day for 6 months. Soldiers began to despise them. They called them dog biscuits. They would trade three dinners for a single fresh egg from a French farmer. The Kration was designed for short-term survival, a few days of highintensity combat, but because they were so effective and so easy to ship, the army started issuing them for months at a time.

The troops hated them, but they kept them alive. The Kration wasn’t designed to be enjoyed. It was designed to be burned. But look at the modern battlefield today. If you look at a United States Army MRE, the meal ready to eat, you are looking at the direct descendant of the Kration. Open an MRE today. What do you see? A waterproof heavyduty plastic pouch.

Inside a main entree, a cracker, a spread, a dessert, and yes, often a caffeinated beverage or gum. The technology has improved. We have flameless ration heaters and better menus now. But the DNA is identical. Every modern field ration in the world, from the British 24-hour ration to the Russian IRP, owes its existence to that trip to the Minneapolis grocery store in 1941.

Anel Keys proved that you don’t feed a modern army with field kitchens and livestock. You feed them with calories calculated down to the gram packaged to survive the apocalypse. The Kration is the unsung hero of World War II. It doesn’t get the glory of the Sherman tank or the P-51 Mustang. It sits in the background of every photo, a crumpled box in the mud next to the heroes.

But make no mistake, the Allies didn’t just win the war because they had the biggest guns or the bravest men. They won because they had a scientist who realized that in a war of speed and movement, sometimes a stick of gum and a cracker is more dangerous than a bullet. Dr. Anel Keys didn’t just pack a lunch. He packed the fuel that burned down the Third Reich.

The war ended in 1945, but the battle against the limits of the human body never stopped. If you talk to a veteran of the Second World War today, if you can still find one, and you mention the Kration, they will likely grimace. They will tell you about the menu fatigue. They will describe the taste of that potted meat as something akin to salty rubber. They hated it.

But in that hatred lies the ultimate vindication of Ensulks. They hated it, but they were alive to complain about it. That is the paradox of military engineering. The most successful inventions are often the ones the soldiers complain about the most, right up until the moment it saves their lives. Fast forward 80 years.

Go to a forward operating base in Afghanistan or a training ground in Fort Bragg. Watch a modern infantryman take a knee during a lull in the fighting. He pulls out a beige plastic pouch. It’s the MRE, the meal ready to eat. He tears it open. Inside he finds a pouch of beef stew, a cracker, peanut butter, and a flameless chemical heater.

He adds a splash of water, leans it against a rock or something, and in 5 minutes, he has a hot meal. That plastic pouch is the direct genetic descendant of the wax box ancel keys glued together in 1941. The technology has evolved. We’ve traded wax for polymers and cans for vacuum seals, but the philosophy is identical. Every time a modern soldier rips open a jalapeno cheese spread or downs a packet of electrolyte powder, they are interacting with the ghost of Ancel Keys.

Keys change the fundamental math of warfare. Before him, an army was a biological organism that needed to begrazed and watered like cattle. After him, the soldier became a self-contained energy system. This shift had consequences that ripple through to the civilian world today. The energy bar you eat after a workout, that’s a K-ration. The freeze-dried camping food you take hiking, that’s a K-ration.

The entire concept of processed, shelf stable, high calorie portable nutrition didn’t come from a chef. It came from a physiologist trying to figure out how to keep a paratrooper from passing out in a ditch in France. Ancel Keys proved that you don’t win wars with rigid tradition. You win them with adaptability. He looked at a problem that generals thought required heavy trucks and field kitchens, and he solved it with a trip to the grocery store.

He understood that in the hell of combat, when your hands are shaking too much to use a can opener and the mud is freezing your boots to the ground, complexity is the enemy. Simplicity is survival. The US Army conquered the world not just because they had the best tanks or the most airplanes or the atomic bomb. They won because they had a scientist who realized that the human engine is the most important machine on the battlefield.

And he realized that sometimes a stick of gum and a cracker is more dangerous than a bullet. The story of Ancel Keys doesn’t actually end with the surrender of Germany or Japan. Because once the shooting stopped, a new enemy appeared. Starvation. Europe was a graveyard. Millions of civilians were surviving on less than 800 calories a day.

The Allies had won the war, but they had no idea how to safely bring a starving population back from the brink of death without killing them. So, Dr. Keys went back to work. While the ticker tape parades were happening in New York, he was conducting the Minnesota starvation experiment. He took conscientious objectors, volunteers, and deliberately starve them for months to study the psychological and physical effects of hunger. It was brutal.

It was controversial. But the data he gathered literally wrote the manual on how to save Europe. The kration fueled the soldiers who liberated the continent. His starvation study fueled the relief effort that rebuilt it. There is a profound irony in the life of Ansulks. He is the man who invented the most processed high calorie artificial food in history to win a war.

But later in life, he became famous for something completely different. He is the father of the Mediterranean diet. He spent his post-war life trying to convince Americans to stop eating processed meat and start eating olive oil and vegetables to save their hearts. He spent the first half of the 1940s figuring out how to pack calories into soldiers to keep them alive and the rest of his life figuring out how to take calories out of civilians to keep them from dying.

But to the men of the 101st Airborne shivering in the snow of the Arden Forest in 1944, he wasn’t the cholesterol guy. He was the guy who put a stick of gum and a cracker in their pocket so they could live to see another sunrise.

News

The US Army Needs Mobility — So They Make A Jeep Assembled In 4 Minutes

The US Army Needs Mobility — So They Make A Jeep Assembled In 4 Minutes 4 minutes. That was…

The US Army Was Losing Tanks on Cobblestone — So a Mechanic Put Wheels on a M18 Hellcat.

The US Army Was Losing Tanks on Cobblestone — So a Mechanic Put Wheels on a M18 Hellcat. Imagine for…

The Surprising Reason This Aircraft Survived 20 Enemy Hits

The Surprising Reason This Aircraft Survived 20 Enemy Hits Tunis, North Africa, February 1, 1943. 26,000 ft. The sky over…

German U-Boat Commanders Were Terrified By The US Navy’s Hunter-Killer Tactics

German U-Boat Commanders Were Terrified By The US Navy’s Hunter-Killer Tactics In early 1943, the fate of the free world…

German Child Soldiers Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Hamburgers Instead

German Child Soldiers Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Hamburgers Instead April 22nd, 1945. Camp Carson, Colorado. The gravel…

The US Army Couldn’t Move In Winter — So They Built A Jeep That Could Go On Snow.0[;’

The US Army Couldn’t Move In Winter — So They Built A Jeep That Could Go On Snow. Look closely…

End of content

No more pages to load