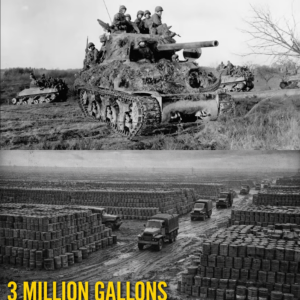

Americans Had 3.3 Million Gallons Of Fuel At Two Depots While German Tanks Ran Dry

December 17th, 1944. Near Stavolo, Belgium. The fuel gauge read empty, but Obersturmführer Joachim Peiper of Kampfgruppe Peiper, 1st SS Panzer Division, knew that already. Through his commander’s periscope, he watched American trucks streaming past on the distant road, each burning more fuel in an hour than his entire column possessed.

His Tiger II sat immobilised, its 860-litre tank drained after consuming its last drops just three kilometres from the greatest prize of Operation Watch on the Rhine, a massive American fuel depot containing 2.2 million gallons of gasoline near Spa. In his post-war testimony at the Dachau trials, Piper would recall this moment with bitter clarity.

We could smell the gasoline. The greatest fuel depot in Belgium lay just beyond our reach. My vehicles sat like monuments to our failure, perfect machines rendered useless by empty tanks. The Americans had so much fuel they would later burn over a million gallons rather than let us capture it.

Through his binoculars, Piper could see the depot’s outer perimeter. Belgian civilians and American engineers were already preparing to destroy what couldn’t be evacuated. By his calculation, visible alone was enough fuel to operate his entire Kampfgruppe for six months. The Americans had accumulated more fuel at this single location than the entire 6th SS Panzer Army possessed for the Ardennes offensive.

The mathematics of defeat were being written in litres and gallons, in the vast gulf between American abundance and German scarcity. The crisis that would strangle the Wehrmacht in the Ardennes had roots in Germany’s fundamental resource poverty. Wehrmacht records in the Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv reveal the stark mathematics. In 1941, Germany produced 5.7 million tonnes of oil annually, including synthetic production from coal.

The United States alone produced 180 million tonnes, with access to another 300 million tonnes from Allied sources, a 100 to 1 disadvantage that no amount of tactical brilliance could overcome. For the Ardennes offensive, Hitler had promised Field Marshal von Rundstedt five million gallons of fuel.

The Wehrmacht managed to stockpile approximately that amount, but transportation bottlenecks meant only 3.17 million gallons were actually available when the offensive began on December 16th. Even this allocation, larger than initially planned, provided fuel for only six days of operations. German general staff calculations showed they had enough fuel for one-third to one-half the distance to Antwerp under combat conditions.

Major Joachim Dietrich, quartermaster of the 2nd Panzer Division, recorded the impossible arithmetic in his war diary. Fuel per vehicle, enough for 90 to 100 miles. Distance to Antwerp, 125 miles minimum. Fuel required for combat manoeuvring, double the standard rate. We are ordered to capture American supplies to continue.

The entire operation depends on stealing enemy fuel. While German tanks would soon sit immobilized awaiting fuel, the Americans had created the most extraordinary logistics operation in military history. The Red Bull Express, operating from August 25 to November 16, 1944, delivered 12,500 tons of supplies daily at its peak, along a dedicated highway system stretching from the Normandy beaches to the front lines.

First Lieutenant Charles Waco, of the 3632 Quartermaster Truck Company, an African-American unit forming the backbone of the operation, documented the scale. My company alone moved 50,000 gallons in a good day. We burned 300,000 gallons daily just operating our trucks. More fuel consumed delivering fuel than the Germans had for combat.

Yesterday a driver spilled 50 gallons missing a tank opening. The lieutenant said, that’s why we bring extra. Nobody counted gallons. We counted tanker ships. The statistics from Transportation Corps records reveal the scope. 6,000 trucks operated continuously on exclusive military highways. In 82 days, they delivered 412,193 tonnes of supplies to the advancing armies.

While fuel wasn’t the only cargo, petroleum products constituted the largest single category, enabling Patton’s 3rd Army and Hodge’s 1st Army to consume their combined 800,000 gallons daily during the pursuit across France. Unknown to the Germans plotting their December 800,000 gallons daily during the pursuit across France.

Unknown to the Germans plotting their December offensive, the Allies had accomplished an engineering miracle that made fuel scarcity obsolete. Operation Pluto, pipeline under the ocean, had laid flexible pipelines across the English Channel.

After initial difficulties by December 1944, the system was approaching its capacity of one million gallons daily. Captain Bernard Williams, a petroleum engineer from Standard Oil supervising Pluto operations, recorded, We’re pumping 3,000 tons of fuel daily through underwater pipes. The Germans are calculating fuel by the barrel while we measure by the tanker load.

This single pipeline delivers more daily than Germany’s entire synthetic fuel industry produces. The pipeline network extended across liberated Europe. By December 1944, Americans had constructed 3,000 miles of fuel pipelines across France and Belgium, creating a petroleum circulatory system that delivered fuel like blood through arteries. Every major depot connected to this network could receive unlimited supplies, regardless of weather or enemy action.

The fuel depot complex between Spa and Stavelo represented American logistics doctrine at its most abundant. Depot No. 2 near Spar contained 2,226,000 gallons. Depot No. 3 at Stavelo held 1,115,000 gallons. Together, over 3.3 million gallons, more than the Germans had allocated for their entire offensive, sat in this one sector.

Staff Sergeant James Morrison of the 25th Quartermaster Battalion described the Stavolo depot. Mountains of jerry cans stacked like pyramids, underground storage tanks, fuel trucks parked in rows. Yesterday HQ sent another 200,000 gallons. I asked where we’d put it. Captain said stack it higher.

We had so much that when Piper got close, we just burned what we couldn’t move. 124,000 gallons up in smoke like it was nothing. The depot’s records reveal American fuel wealth. Daily receipts averaged 200,000 gallons, daily distribution 180,000 gallons, creating ever-growing reserves. By December 17th, when Piper’s spearhead approached, these depots contained enough fuel to operate every vehicle in the German Wehrmacht for four months.

German tanks advancing through the Ardennes represented superb engineering shackled by catastrophic consumption rates. The Tiger II’s Maybach engine delivered 700 horsepower but drank 2.75 gallons per mile on roads, 5.5 gallons per mile cross-country. A Tiger II’s 860-litre capacity meant a combat radius of perhaps 60 miles before requiring refuelling. Feldwebel Hans Zimmermann, driver of Tiger II No.

332, documented the crisis. Started December 16th with full tanks. By noon, down to half after 35 kilometres, American fighter bombers forced us off-road. Cross-country movement doubled consumption. By nightfall, nearly empty. Ordered to continue advancing.

With what fuel? Panther tanks, theoretically more efficient, achieved barely 0.5 miles per gallon in combat. A Panther battalion’s 60 tanks required 15,000 gallons to move 30 miles under fire. Kampfgruppe Peiper’s entire fuel allocation, 180,000 gallons, meant enough for one major engagement, nothing for exploitation. Peiper himself testified at Dachau.

We were told to drive until the tanks stopped, then capture American fuel. This wasn’t a military operation but organised banditry. We weren’t soldiers but fuel thieves, and we failed even at that. The most significant German fuel capture occurred at Bullingen on December 17th.

A Kampfgruppe-Piper detachment discovered an American fuel dump containing 50,000 gallons, guarded by only a handful of rear echelon troops who fled when German tanks appeared. Unterscharführer Georg Fleps recalled, We couldn’t believe it. Jerry cans stacked everywhere, fuel trucks with keys in the ignition. We filled every tank, every container.

It was like finding water in the ignition. We filled every tank, every container. It was like finding water in the desert. But even this windfall, 50,000 gallons, would barely get us to the muse. The captured fuel revealed another dimension of American superiority. Every can bore octane ratings, 80, 85, 100 octane. Americans had different grades for different purposes, high octane for aircraft, middle grades for trucks, specialized fuels for various engines.

Germans, when they had fuel at all, made do with synthetic gasoline of such poor quality, it damaged engines and reduced performance by 20%. At Bullingen, Piper’s men also captured 50 American prisoners. In a war crime that would feature prominently at his trial, these prisoners were forced to fuel German vehicles before being executed, a grim testament to German desperation for petroleum.

On December 18th at Trois-Ponts, Piper’s advance met disaster, not from enemy fire but from demolished bridges. Major Robert Bull Yates’s engineers of the 51st Engineer Combat Battalion blew the Amblev Bridge at 11.45am and the Salm Bridge at 1pm, just as German vehicles approached. These demolitions forced Piper north toward La Glaze, away from the massive fuel depots he desperately needed to capture.

Captain John Wilson of the 291st Engineers recalled, We could see their lead tanks approaching, Tigers and Panthers, magnificent machines. But we knew they were running on fumes. Every bridge we dropped forced them to burn fuel finding alternate routes. We were defeating them with TNT and time, making them waste what they couldn’t spare. The bridge demolitions at Trois-Ponts proved decisive.

Piper’s detour consumed precious fuel, and by the time his forces reached La Glaze, most vehicles were running on their last reserves. They had travelled less than fifty miles from their start line. By December 19th, Piper’s spearhead reached La Glaze, tantalisingly close to the 2.2 million gallon depot near Spa.

But his vehicles were dying of thirst. American forces had successfully evacuated most of the depot’s fuel, and what remained would be destroyed rather than captured. Piper radioed desperately for fuel. The Luftwaffe attempted an aerial resupply on December 22, but of 35 U-52 transport planes dispatched, only 10 reached the drop zone, delivering 1,100 gallons, enough for perhaps 10 tanks to move 10 miles. Most containers burst on impact or fell into American hands.

By December 24, Christmas Eve, Piper faced reality. Starting with 4,800 men and 800 vehicles, including 117 tanks, he now commanded immobilized steel monuments to German fuel poverty. He would abandon 135 vehicles at La Glaze, six Tiger IIs, 13 Panthers, six Panzer Fus, 50 other armored vehicles, almost all mechanically perfect but without fuel.

I had the finest tank crews in the Wehrmacht, Peiper testified, commanding the most powerful tanks ever built. We abandoned them not from enemy action but from empty fuel gauges. We walked out on foot like beggars while Americans drove past in endless columns. At the Malmedy crossroads on December 17 17, Kampfgruppe Peiper committed the war’s most notorious massacre in the Western Front, murdering 84 American prisoners from the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion. While the massacre’s primary motive was maintaining

operational tempo, the broader context of fuel desperation permeated German actions throughout the offensive. Technical Sergeant William Merican, who survived by playing dead, testified, They were in a hurry, checking their watches constantly. I heard officers arguing about fuel consumption, about making speed.

They killed us because we would slow them down and they couldn’t afford delay. The irony was bitter. Germans murdered prisoners to save time, yet still ran out of fuel before reaching their objectives. The Malmedy massacre would become symbolic of German barbarity, but also of their desperation. As German tanks sat immobilized, American forces demonstrated casual fuel abundance that demoralised enemy observers.

Sherman tanks kept engines running continuously in freezing weather, burning fuel for crew comfort. Jeeps drove two blocks rather than walking. Generators powered electric lights, movie project, and coffee makers throughout the night. Private First Class Anthony Caruso of the 3915 Quartermaster Gas Supply Company described routine waste.

We drained old fuel from tanks after three days and replaced it with fresh. Germans POWs watching us dump hundreds of gallons nearly rioted. One sergeant begged to collect discarded fuel in his canteen. When we laughed, he said we were laughing at Germany’s grave. Captain Robert Johnson of the 14th Cavalry Group reported, My squadron burned more fuel staying warm last night than a German panzer company possesses for combat.

We measure fuel by the depot, they measure by the jerry can. This isn’t warfare between equals, it’s industrial abundance crushing industrial poverty. By late December, American engineers had extended fuel pipelines to within 30 miles of the front lines. The advancing pipeline represented American doctrine. the front lines. The advancing pipeline represented American doctrine, permanent infrastructure following combat forces, ensuring unlimited fuel supply regardless of tactical situation.

Captain Eugene Smith, 697th Engineer Petroleum Distribution Company, described the work. We laid pipe across the Ardennes battlefield while German bodies were still warm. By January 1st, we were pumping 100,000 gallons daily to locations the Germans had abandoned for lack of fuel. Every mile of pipe we laid was another nail in their coffin.

The pipeline from Cherbourg to the German border could deliver 4 million gallons daily without using a single truck. the German border could deliver 4 million gallons daily without using a single truck. This infrastructure made American forces effectively immune to the fuel constraints that paralysed German operations.

The relief of Bastogne demonstrated American fuel supremacy at its most dramatic. Patton’s Third Army pivoted 90 degrees, moving three divisions over 100 miles in freezing conditions to strike the German flank. This manoeuvre consumed 800,000 gallons in 72 hours, nearly the entire German fuel allocation for the offensive. Colonel Walter Muller, Patton’s logistics officer, recorded, Patton asked if we had enough gas.

I showed him the numbers, two million gallons in reserve, another million arriving daily. He said, stop counting and start driving. We burned more fuel reaching Bastogne than the Germans had to reach Antwerp. Meanwhile, German forces attempting to capture Bastogne were already rationing fuel. The 2nd Panzer Division, closest to the Meuse River, had travelled 60 miles on fuel meant for 30.

They sat immobilised within sight of their objective, begging for fuel that didn’t exist. The surrounded 101st Airborne at Bastogne provided another demonstration of American logistics supremacy. Despite complete encirclement, they never lacked fuel for vehicles, generators or heating. C-47 transports flew in supplies, including 5,000 gallons of fuel in specially designed crash-resistant containers.

Sergeant Joseph Borelli of the 326th Engineer Battalion described the drops. Germans watched from the woods as parachutes delivered jerry cans. German prisoners helped collect containers, shaking their heads in disbelief. One said, You fly gasoline? You have so much you fly it? He wasn’t angry, just broken.

The Luftwaffe, struggling to fuel its remaining aircraft, watched American planes burn thousands of gallons to deliver thousands more, a circular logic of abundance that shattered German morale more effectively than artillery. Christmas Day. 1944 marked the complete collapse of German fuel logistics.

Across the Ardennes, German vehicles sat abandoned, not destroyed but simply empty. The 2nd Panzer Division at Seles, having advanced furthest west, was annihilated when it ran out of fuel just three miles from the Meuse. Major Hans von Luck, attempting to withdraw the 116th Panzer Division, described the catastrophe.

American vehicles lined up at field fuel points, like peacetime filling stations. Soldiers with hoses filled tanks as casually as pre-war attendants. My own Panthers sat empty 500 metres away. We destroyed them ourselves and walked into captivity. We destroyed them ourselves and walked into captivity.

At Schaeff headquarters, Eisenhower’s logistics staff reported fuel stocks, 42 million gallons in theatre, 1.5 million gallons arriving daily. The German offensive had increased American fuel consumption from 800,000 to 1.2 million gallons daily, treated as a minor fluctuation.

They still maintained 35 days of reserves. The most powerful symbol of German defeat was King Tiger 332, abandoned near La Glaze with an empty fuel tank but otherwise perfect condition. This 68-tonne masterpiece of engineering, virtually impervious to Allied guns, was defeated by an empty fuel gauge. The tank’s commander, Obersturmführer Kurt Knispel, Germany’s highest-scoring tank ace with 168 confirmed kills, wrote his final combat report, Destroying my vehicle for lack of fuel. Engine perfect, gun operational, armor intact.

But the fuel tank is empty. We are defeated by absence. The absence of gasoline, which the Americans possess in infinite quantity. American forces found the destroyed King Tiger the next day. Beside it lay a carefully coiled siphon hose, the final tool of an army reduced to stealing drops while its enemies swam in oceans of petroleum.

Captured German officers provided devastating insights into fuel poverty. Major Heinrich Goerzel, quartermaster of 2nd SS Panzer Division, captured December 26, revealed the impossible mathematics. Your smallest depot contains more fuel than my entire division received. You measure in tanker ships what we measure in barrels.

This isn’t war, it’s industrial annihilation. When shown American supply records, 100,000 gallons daily for an armoured division, supply records, 100,000 gallons daily for an armoured division, Goesel refused to believe it until presented with actual receipts. His response? Then why continue fighting? You’ve already won. We are dead men walking in empty tanks.

Oberst Friedrich von Melanthin, operations officer for Army Group B, compiled the final arithmetic. operations officer for Army Group B, compiled the final arithmetic. Fuel required for Antwerp, 4.5 million gallons. Fuel available, 3.17 million gallons. Fuel delivered to units, 2.1 million gallons. Fuel consumed by December 24th, 2.0 million gallons.

Fuel captured, 200,000 gallons. Result, complete immobilization. The fuel crisis strangling German ground forces connected directly to the American strategic bombing campaign. By December 1944, American bombers had reduced German synthetic fuel production by 90%. The Lohner plant, once producing 2,000 tonnes daily, operated at 10% capacity.

On December 24, as German tanks scraped their last drops, 2,034 American bombers attacked German rail yards and fuel facilities. This single mission consumed 5.5 million gallons of aviation fuel, nearly double Germany’s entire allocation for the Ardennes. Lieutenant General Karl Spatz calculated the exchange.

We burn 5 million gallons to destroy their capacity to produce 50,000 gallons. The arithmetic is extravagant but decisive. We trade abundance for their scarcity. American combat engineers demonstrated another dimension of fuel superiority.

The 291st Engineer Combat Battalion defending Malmedy used bulldozers, cranes and compressors, consuming 5,000 gallons daily just maintaining roadblocks. Their D-7 bulldozers burned 50 gallons per hour operating continuously. German pioneers, observing through binoculars, reported the impossible profligacy. Hauptmann Werner Kempfer, 12th SS Pioneer Battalion, wrote, Americans use machines for everything, gasoline-powered saws, pneumatic drills, mechanized bridge layers.

Tasks requiring our manual labor for days, they accomplish in hours with machines burning unlimited fuel. The Ardennes Offensive revealed fuel as the controlling factor in modern warfare. offensive revealed fuel as the controlling factor in modern warfare.

Germany had assembled 250,000 men, 1,400 tanks and assault guns, and 2,600 artillery pieces, a formidable force rendered impotent by petroleum poverty. Field Marshal Walter Model’s final assessment was blunt. We cannot withdraw mechanized forces. We lack fuel to save what we lack fuel to operate. Americans advance not through superior tactics but through gasoline. They win because they have petroleum. We lose because we don’t.

The numbers told everything. American fuel available in theater, 180 million gallons. German fuel for offensive 3.17 million gallons daily American delivery capacity 4 million gallons daily German production 40,000 gallons ratio 100 to 1 behind the battlefield mathematics lay industrial reality American refineries produced 5 million barrels daily.

The Texas-Louisiana refinery complex alone outproduced the entire axis. The Baytown refinery processed 10 million gallons daily, more than Germany’s entire synthetic fuel industry. German synthetic fuel plants, engineering marvels producing gasoline from coal, represented desperate improvisation against geological reality.

Despite inventing the process, Germany never exceeded 120,000 tons monthly. American natural petroleum production reached 15 million tonnes monthly. Dr Heinrich Buttefisch, former IG Farben synthetic fuel director, admitted post-war, We spent billions of Reichsmarks creating what Americans pumped from the ground.

They burned excess fuel in flares while we measured by the drop. This wasn’t technological competition, but resource infinity versus scarcity. By January 28th, 1945, the Ardennes Offensive had completely collapsed. German forces abandoned 15,000 vehicles during retreat, most from fuel exhaustion rather than combat damage.

The Wehrmacht lost 600 tanks and assault guns, approximately 400 from empty fuel tanks. American forces, conversely, had consumed 50 million gallons during the battle, more fuel than Germany possessed nationally. They ended the battle with larger reserves than when it began, testament to their logistics pipeline delivering 1.5 million gallons daily throughout the fighting.

their logistics pipeline delivering 1.5 million gallons daily throughout the fighting. The 463rd Ordnance Evacuation Company recovered German vehicles after the battle. Their inventory revealed the pattern. Tiger IIs abandoned with full ammunition. Panthers destroyed by their crews for want of 100 gallons. Assault guns pushed into ditches when fuel ran out.

Each vehicle a monument to petroleum poverty. The Battle of the Bulge proved that modern warfare was won in oil fields and refineries, not just battlefields. Germany brought tactical brilliance, superior tanks, and veteran crews to the Ardennes. America brought gasoline, unlimited, abundant, overwhelming gasoline. General Eisenhower understood this reality.

The Germans had excellent soldiers, superior tanks in many cases, defensive advantages. But they measured fuel by the barrel while we measured by the tanker ship. This disparity made victory inevitable. The German offensive, Hitler’s last gamble, was doomed before the first shot. The Wehrmacht needed to capture American fuel to continue, but American fuel abundance meant even massive captures wouldn’t matter.

Losing three million gallons at Spa-Stavelot was an inconvenience for Americans. For Germans, failing to capture it meant defeat. The Ardennes battle marked warfare’s transformation from martial contest to industrial competition. Victory belonged not to the bravest soldiers or best tactics, but to whoever could deliver the most fuel to the battlefield.

tactics, but to whoever could deliver the most fuel to the battlefield. American doctrine embraced this reality, overwhelming logistics supporting continuous operations. German doctrine, rooted in operational excellence, couldn’t overcome resource scarcity. The finest tank crews, commanding the most powerful tanks ever built, were defeated by empty fuel gauges.

most powerful tanks ever built were defeated by empty fuel gauges. Colonel Creighton Abrams, commanding the 37th Tank Battalion that helped relieve Bastogne, captured this transformation. I never check fuel levels. I tell logistics where I’m going and assume gasoline will be there. It always is. Germans counted every litre while we counted victories. For Germany, the Ardennes taught a bitter lesson about modern war’s requirements.

Courage couldn’t overcome chemistry. Will couldn’t create petroleum. The Wehrmacht that had conquered Europe with tactical innovation was crushed by American industrial capacity. Former Luftwaffe General Adolf Galland summarized, We learned that modern war isn’t won by warriors but by factory workers, not by heroes but by petroleum geologists. The Americans didn’t defeat our army, they drowned it in gasoline.

The abandoned vehicles littering the Ardennes told the story. Mechanical perfection rendered useless by empty tanks. German engineering excellence meant nothing without fuel to power it. The King Tigers and Panthers, masterpieces of armoured warfare, became 68-tonne monuments to one simple fact. In modern war, the army with the most fuel wins.

The fuel crisis of December 1944 cast a long shadow over military thinking. Future armies would learn from Germany’s catastrophe. Never launch operations beyond your fuel supply. Never depend on capturing enemy resources. Never underestimate logistics. For America, the Ardennes validated their logistics-first approach. The ability to deliver millions of gallons anywhere, anytime, under any conditions became the foundation of American military supremacy.

Every subsequent American military operation would prioritize fuel supply above all else. The German veterans who survived would carry the trauma of fuel starvation permanently. In post-war memoirs, the phrase empty tank appears more frequently than enemy fire. They were defeated not by American soldiers, but by American abundance. In the end, the Battle of the Bulge was decided in the oil fields of Texas and Oklahoma, not the forests of Belgium.

The 2.2 million gallons at Spa that Piper couldn’t reach was pocket change in American terms, replaced within two days. For Germany, it represented more fuel than entire army groups possessed. The battle proved that industrial capacity trumped military skill in modern warfare. American forces didn’t need to be better soldiers when they could be better supplied.

They didn’t need superior tactics when they had superior logistics. They didn’t need to count fuel when they had infinite amounts. As German tanks sat frozen and empty in the Ardennes snow, American vehicles rolled past in endless columns, engines running continuously, burning fuel with the casual indifference of unlimited supply.

Each gallon burned was a statement of supremacy, each full tank a declaration of victory. The greatest tank battle in the Western Front ended not with climactic combat, but with the quiet death of engines running dry. The silence of empty fuel tanks spoke louder than artillery.

German crews walked away from perfect machines they couldn’t fuel while Americans drove past in inferior tanks they could fuel forever. The Ardennes Offensive failed because it challenged arithmetic with ideology, attempting to overcome infinite resources with finite courage. The 2.2 million gallons near Spa and 1.

1 million at Stavolo represented not just fuel, but American industrial civilization’s answer to German military prowess, overwhelming abundance that made courage irrelevant and skill meaningless. In those frozen December days, beside immobilised Tigers and abandoned Panthers, German soldiers learned the final lesson of industrial warfare. Modern war is won not by the army with the best soldiers, but by the nation with the most fuel.

They had challenged an enemy who measured petroleum by the tanker ship while they measured it by the jerry can. The outcome was predetermined by geology and geography, by oil wells and refineries, by pipelines and tanker ships. The Battle of the Bulge ended as it had to end, with German tanks sitting empty while American abundance flowed endlessly forward, carrying with it the inevitability of victory.

News

Here’s The Real Reason Why Tyler Loop Missed His Game-Winning Field Goal Attempt That Everyone Needs To Know About [VIDEO]

Tyler Loop had higher powers working against him on his missed field goal. You can point to several reasons why…

Hermann Göring Laughed At US Plan For 50,000 Planes – Then America Built 100,000

Hermann Göring Laughed At US Plan For 50,000 Planes – Then America Built 100,000 May 28th, 1940. Reich Air Ministry,…

German POWs Couldn’t Believe Ice Cream And Coca-Cola in American Prison Camps

German POWs Couldn’t Believe Ice Cream And Coca-Cola in American Prison Camps Summer 1943. Camp Crossville, Tennessee. The brown liquid…

German Troops Never Knew American Sherman Tanks Had The World’s Most Advanced Radios

German Troops Never Knew American Sherman Tanks Had The World’s Most Advanced Radios February 20th, 1943, north of Casarin Pass,…

German Colonel Captured 50,000 Gallons of US Fuel and Realized Germany Was Doomed

German Colonel Captured 50,000 Gallons of US Fuel and Realized Germany Was Doomed December 17th, 1944. 0530 hours. Hansfeld, Belgium….

German Pilots Laughed At The P-47 Thunderbolt, Until Its Eight .50s Rained Lead on Them

German Pilots Laughed At The P-47 Thunderbolt, Until Its Eight .50s Rained Lead on Them April 8th, 1943. 27,000 ft…

End of content

No more pages to load