Dean Martin Saw Jerry Lewis Mocking Him Onstage — What He Did Next Created a Legend

The young man stumbled forward and climbed onto the stage behind Dean Martin, swaying slightly as he found his footing. And Dean kept singing like nothing had changed, his voice smooth and steady on the second verse until the man scrunched up his face and started mimicking every move Dean made. And that’s when the audience began to laugh.

And Dean’s voice caught on a single note, trembling there for just a fraction too long. Wait. Because when Dean turned around and saw that man standing there, his hand closed into a fist and the room went silent. And what Dean chose to do in the next 5 seconds would change not just that night, but two men’s lives forever.

And almost nobody understood what it cost him. The Havana Club sat on 49th Street in Manhattan, wedged between a delicatessan that smelled like pickles and a dry cleaner that never quite got the chemical smell out of the air. It wasn’t the kind of place where careers were made. It was the kind of place where careers went to die quietly with dignity if you were lucky, without it if you weren’t.

The stage was 8 ft deep and 12 ft wide. just enough room for a small band and a singer who didn’t move around too much. The tables were packed close together. Round tops covered in white cloth that had been washed so many times the fabric felt thin as paper. Cigarette smoke hung in layers under the chandeliers. Blue gray clouds that caught the stage lights and turned them hazy.

Dean Martin had been singing at the Yavana Club for 6 months. The owner, a man named Lou Walters, sat at his usual table in the back corner near the kitchen door where he could see everything and leave quickly if he needed to. Lou had told Dean 3 days ago that the contract wouldn’t be renewed. Nothing personal, Lou had said, stirring his coffee with a spoon that clinkedked against the porcelain.

The audience is bored. Singers are a dime a dozen in New York. Dean had nodded. smiled that easy smile of his and said he understood, but his hands had been shaking when he lit his cigarette in the alley afterward. This was Dean’s last night, Tuesday, March 19th, 1946. He’d sung the first song, I’ll walk alone, and the applause had been polite, but then the kind of clapping that stops the moment people remember they’re holding drinks.

Now he was halfway through. You made me love you. And he could see what was happening. Three couples near the front were putting on their coats. A man at table 7 was waving for the check. Two women by the bar had turned their backs to the stage entirely, leaning close to gossip about something more interesting than a second rate kuner going through the motions.

Dean kept singing. That’s what you did. The show must go on even when nobody’s watching. Even when your throat feels tight and your fingers are cold around the microphone stand, he focused on the back wall just above Lou’s head and let the words come out automatically. The band was good tonight.

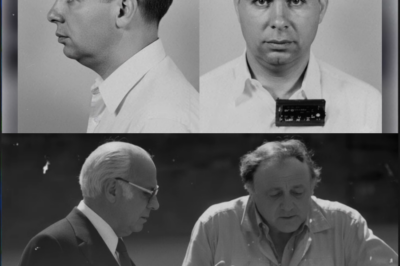

Eddie on piano, Tommy on bass, a kid whose name Dean could never remember on drums. They were locked in, steady, giving him everything they had, even though they knew this was the end. Look at Dean’s face in that moment. really look at it. He’s smiling, but it’s not reaching his eyes. There’s a tightness around his mouth, a small muscle jumping in his jaw.

He’s 28 years old, and he’s been doing this for almost 10 years, singing in clubs like this. Always one step away from going back to Stubenville, Ohio to work at the steel mill or deal cards at the illegal gambling hall like he did when he was 17. His mother’s voice is in his head, the way it always is when things go wrong.

Dino Quando Toriasa, when are you coming home? Jerry Lewis was sitting at table 12 near the stage, but off to the left, nursing a ginger ale because he didn’t drink. He was 20 years old, skinny as a fence post with dark curly hair and eyes that moved constantly, watching everything. Jerry was a comedian or trying to be. He did a record act, pantoimeing to records while doing physical comedy, and he’d been working the same circuit of small clubs for two years.

Lou had promised Jerry a slot tonight. After Dean finished 10 minutes, Lou had said, “Make them laugh and maybe I’ll book you regular.” But Jerry was watching Dean die up there, watching the audience lose interest, watching Lou check his watch. And Jerry understood what was about to happen. If Dean bombed, Lou would close the night early, send everyone home.

Jerry wouldn’t get his 10 minutes. More than that, though, Jerry was watching Dean’s hands. The way they gripped the microphone stand a little too tight, and he recognized something. Desperation. The same thing Jerry saw in the mirror. Every morning, Dean hit the bridge of the song, the part where the melody opens up, and a good singer can really pour emotion into it.

He was giving it everything, but his voice sounded thin in the room, swallowed by the clink of glasses and the murmur of conversations. Four more people stood up, pulling ontheir jackets. Lou was looking at his watch again. That’s when Jerry stood up. Remember this, because what happens next only makes sense if you understand what Jerry was thinking.

He wasn’t drunk despite how it looked. He wasn’t trying to sabotage Dean. Jerry was making a calculation, the kind desperate performers make when they see their shot disappearing. If he could get the audience’s attention, maybe save Dean’s set, maybe Lou would keep the night going. Maybe Jerry would still get his 10 minutes.

Or maybe if Jerry was being honest with himself in that split second, he just couldn’t watch another performer fail without trying to do something. Jerry walked toward the stage, weaving between tables, and he exaggerated his movements just slightly. Made it look like he’d had a few drinks. People noticed him. A woman at table six whispered to her husband.

The man at table 7 stopped waving for the check and turned to watch. Jerry reached the stage and pulled himself up. One knee first, then the other. And he stood there behind Dean Martin. and Dean kept singing because that’s what you do. You don’t acknowledge the drunk person until they become a problem.

Jerry waited two beats watching Dean and then he did it. He made a face, scrunching up his features and opening his mouth wide, mimicking Dean’s singing posture. A woman near the front laughed, a sharp sound that cut through the music. Jerry did it again, bigger this time. His arms spread wide in a mockery of Dean’s casual stance.

More laughter spreading through the room like fire in dry grass. The couple putting on their coats stopped. The man at table 7 sat back down. Dean heard the laughter and something in his chest went cold. He knew that sound. It was the sound of an audience waking up, but they weren’t waking up for him. He turned his head just slightly, still singing, and he saw Jerry Lewis standing there, this skinny kid in a white shirt making faces behind his back, and the room was laughing at him.

The song had four bars left before the final verse. Dean’s hand tightened on the microphone, his knuckles going white, the band kept playing. Eddie looked up from the piano, saw what was happening, and his fingers fumbled for just a second before he caught the rhythm again. Lou Walters was half standing from his chair, mouth open, ready to bark an order at the bouncer to get the kid off the stage.

Dean Martin had two choices. He could stop singing, turn around, and physically remove this punk from his stage. It would be justified, professional, the right thing to do. Lou might even respect it, might say, “That’s how you handle a situation.” But the song would be ruined. The set would end in disaster, and Dean’s last night at the Havana Club would be remembered as the night some kid made him look like a fool.

Or he could do something else, something he’d never done before, something that went against every instinct he had about control and professionalism and keeping the performance clean. He could go with it. Notice how long that pause was. Not in real time. It was maybe 2 seconds, but in Dean’s head, it stretched out forever.

He saw his career hanging in that moment. Saw all the years of climbing and scraping and almost making it. Saw himself at 40 still singing in rooms like this, or worse, saw himself giving up entirely and going home. He saw Lou’s face. Saw the audience waiting to see what would happen. saw Jerry Lewis standing there with this desperate energy radiating off him.

One turn, one choice, one second that would decide everything. And Dean made his choice. He turned around fully, still singing. And he looked Jerry Lewis dead in the eye. And instead of anger on his face, there was something else. A smile. Not the performer’s smile he’d been wearing all night, but something real.

Something surprised. He kept singing, but he opened his arms like he was inviting Jerry into the song. And Jerry’s face changed. The exaggerated mockery shifting into something more collaborative. Jerry started moving with the music, his physical comedy suddenly working with Dean instead of against him. The room erupted.

Not polite applause, not thin courtesy laughter. real laughter, the kind that comes from the gut, from people genuinely delighted by something unexpected. Dean sang the last verse directly to Jerry, hamming it up, pointing at him, and Jerry reacted to every word with increasingly absurd facial expressions.

When Dean held a long note, Jerry pretended to be blown backward by the power of it. When Dean’s voice went soft, Jerry leaned in, handcuffed to his ear, straining to hear. The song ended. The band hit the final chord. Dean and Jerry both froze in exaggerated poses. For one beat, the room was silent.

Then the applause came, loud and long, and people were standing up, but this time they were standing to cheer, not to leave. Lou Walter sat back down slowly, his hand falling away from his mouth. He’d been about to stop thewhole thing, been about to end Dean’s career at the Havana Club with a snap of his fingers, but now he was watching something he hadn’t seen in his club in years. People were energized.

They were talking to each other, pointing at the stage, smiling. A waiter hurried past Lou’s table with a tray full of drinks. Someone was ordering another round. Dean lowered the microphone and looked at Jerry and Jerry looked back and something passed between them, not words. Understanding, Jerry stuck out his hand.

Dean shook it and the audience loved that too. Applauded the handshake like it was part of the show. What’s your name? Dean said. Quiet enough that only Jerry in the front tables could hear. Jerry Lewis. You got a death wish, Jerry Lewis? Nah, Jerry said, grinning. I got a 10-minute slot after your set. Figured I’d make sure there was somebody left to watch it.

Dean laughed, a real laugh, and it felt strange in his throat because he hadn’t laughed genuinely in weeks. “You want to do another song with me?” Jerry’s eyes went wide. “You serious? Lucha V is going to throw you out if you leave the stage anyway?” Dean said, nodding toward the back. Might as well make it worth the bruises.

Stop for a second and understand what’s happening here. Dean Martin, who’s been told his contract is ending, who’s been watching his career slip away song by song, is making a choice to extend his own execution. He’s inviting this kid, this stranger who just humiliated him in front of a room full of people to stay on stage.

And he’s doing it because something in that moment of chaos felt more alive than anything Dean had felt in six months of professional controlled performances. They did another song. That old black magic. Dean sang it straight. His voice strong and confident now because the pressure was off. The room was already his.

Jerry moved around the stage reacting to the lyrics with physical comedy, creating little vignettes. When Dean sang about being in a spin, Jerry literally spun in circles until he staggered dizzy. When the lyrics mentioned being caught up in magic, Jerry made his hands dance in the air like he was casting spells. The audience was howling between songs.

Dean talked. This is Jerry Lewis, ladies and gentlemen. Found him wandering in off the street. Figured we’d put him to work. Laughter. Jerry made a face like he was offended. Jerry here tells me he’s a comedian. What do you think? Should we let him tell a joke? The audience cheered. Jerry launched into a bit.

Something about trying to order a drink at a fancy restaurant. All physical comedy and voices. And Dean watched him work, saw the skill underneath the chaos, the timing, the way Jerry could read a room. They did a third song. Ain’t that a kick in the head? Wasn’t written yet, but years later when Dean recorded it, he’d remember this night.

Remember the feeling of something unexpected knocking the wind out of him in the best possible way. For now, they did I’ve got the world on a string, and it felt true in a way it hadn’t at the start of the night. Dean sang and Jerry clowned, and the room belonged to them. Lou Walters stood up from his table and walked to the bar.

The bartender, an older man named Frank, who’d been working the Havana Club for 15 years, leaned in. “What are you thinking, Lou? I’m thinking I just saw something,” Lou said quietly. “I’m thinking maybe I was wrong about Martin. You going to renew his contract?” Lou watched the stage, watched Dean and Jerry moving together, watched the audience completely engaged, watched money being spent.

I’m thinking about something else, he said. The set ended 40 minutes after it was supposed to. Dean and Jerry took their boughs, Dean’s arm around Jerry’s shoulders, and the applause was genuine, enthusiastic, the kind of response that makes club owners start doing math in their heads. Dean and Jerry walked off stage together, down the narrow steps, and into the cramped backstage area that smelled like old wood and makeup and sweat.

That was insane, Jerry said, his hands shaking from adrenaline. I can’t believe you let me stay up there. I can’t believe I did either, Dean said. He lit a cigarette, his hands steadier now than they’d been in days. You always crash other people’s sets. First time, Jerry admitted. Won’t lie.

I thought you were going to punch me. I almost did. Dean exhaled smoke, studied Jerry’s face. You’re good, kid. That physical stuff, the timing, it’s solid. Thanks, Jerry said. And he meant it. Coming from another performer, someone who just let him share a stage, it meant something. Listen to this part carefully because this is where the real story starts.

They talked for 20 minutes backstage. Dean and Jerry sitting on boxes of liquor that hadn’t been unpacked yet, sharing a cigarette even though Jerry didn’t smoke. They talked about where they were from, what they wanted, how hard it was to make it in New York. Dean told Jerry about Stubenville, about his mother’s voice inhis head, about the feeling of being almost good enough but never quite there.

Jerry told Dean about his father, about growing up in the business, about years of performing and feeling like he was invisible. “You ever think about working with someone?” Jerry asked. The question casual, but his eyes serious. Like a partner, Dean said. Like what we just did up there, Jerry said. But on purpose. Dean thought about it.

He thought about the feeling on stage. The way the chaos had become something structured. The way Jerry’s energy had lifted his performance instead of drowning it. He thought about Lou’s face, about the audience, about the fact that 30 minutes ago his career was over and now it felt like something was beginning.

We don’t even know each other, Dean said. So, Jerry said, “We knew each other up there.” Before Dean could answer, Lou Walters appeared in the doorway. He looked at both of them, his expression unreadable. Martin Lewis, my office. Now they followed Lou through the narrow hallway to his office, a cramped room with a desk covered in papers and a filing cabinet that didn’t close all the way.

Lou sat down, gestured for them to sit, but there was only one chair, so they both stood. That was something, Lou said finally. I apologize, Jerry started. I shouldn’t have. Lou held up his hand. I’m not interested in apologies. I’m interested in business. He looked at Dean. Your contract’s up tonight. You know that. I know that. Dean said.

Here’s what I’m thinking. L said. You two together, three nights a week. I’ll pay you as a duo, which means less per person than you were making solo, Martin, but more exposure, more people in seats, more drinks sold. He paused. I’m taking a risk here. You’ve known each other for what? an hour. This could fall apart tomorrow.

But what I saw tonight, that’s what people pay to see. That’s magic. Dean looked at Jerry. Jerry looked back. Neither of them spoke for a moment. Then Dean said, “We’d need to rehearse, figure out material. We can’t just wing it every night. You got 3 days.” Lou said. Thursday you start. And Jerry, you’re not climbing on stage uninvited anymore. You’re part of the show.

Jerry’s face split into a grin. Dean felt something in his chest ease, a tightness he’d been carrying for so long, he’d forgotten it was there. This wasn’t the career he’d imagined. It wasn’t the solo Kuner success story, the trajectory toward becoming the next Sinatra. It was something else, something messier and more uncertain, but it was alive.

They shook hands with Lou, all three of them, and then Dean and Jerry walked out of the office together through the club that was still full of people ordering last rounds out onto 49th Street where the air was cold and clean and the city was still awake. One night, one gamble, one partnership born from chaos.

You realize we don’t have any material, Dean said. We’ll figure it out, Jerry said. I don’t do comedy. you did tonight. That was different, Dean said. That was desperation. Best kind, Jerry said, and he meant it. They walked to the corner, stood under a street light that flickered and buzzed. A taxi passed, its tires hissing on the wet pavement.

Somewhere a few blocks away, music was playing. Another club still open. Another performer trying to make it. Three nights a week, Dean said. think we can stand each other that long? Only one way to find out, Jerry said. They worked it out over coffee at an all-night diner, sketching ideas on napkins, Dean humming melodies while Jerry acted out bits with the salt and pepper shakers as props.

The waitress thought they were crazy. Two guys in the corner at 2:00 in the morning, laughing too loud and talking too fast. But she kept the coffee coming because they were tipping well and because there was something infectious about their energy. 3 days later, they were back at the Havana Club. Thursday night, March 22nd, 1946. They’d rehearsed, sort of, running through songs and bits in a cramped rehearsal space.

Jerry had borrowed from another performer, but the truth was they didn’t really know what they were doing. They had rough ideas, loose structures, and a feeling that if they committed completely, the audience would go with them. They were right. The show was chaos, but controlled chaos. Dean sang, Jerry clowned. Dean played the straight man, smooth and unflapable, while Jerry was the wild card, unpredictable and physical.

When Dean sang embraceable You, Jerry hugged him from behind. When Dean tried to deliver a sincere introduction, Jerry made faces behind his back until Dean broke character and laughed. The audience loved every second. Lou watched from his table, doing calculations on a napkin. Three nights a week turned into five. Five turned into a standing engagement.

Word spread. Bookers from other clubs started coming to the Havana to see what everyone was talking about. Within two months, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis had offers from bigger venues, better money,the chance to take this partnership on the road. A man named Abby Gresler sat in the audience one night in May.

He was a booking agent, well-connected, the kind of man who could open doors or keep them closed. He’d come to see a different act, a piano player who’d cancelled at the last minute, and Lou had convinced him to stay for Martin and Lewis. Abby watched the whole show, stone-faced, taking notes. When it ended, he went to Lou’s office.

“I want to represent them,” Abby said. “They’re not a real act yet,” Lou said. “This is still new. That’s exactly when you sign them.” Abby said, “Before they know what they’re worth.” Abby Gresler became their agent. He got them better clubs, longer sets, more money. He got them a radio spot, then another, then a regular segment.

He got them in front of people who mattered, people who could take them from nightclubs to theaters, from theaters to Hollywood. Years later, when Martin and Lewis were among the biggest acts in America, when they were making movies and filling arenas, when their names were known from coast to coast, reporters would ask them about that first night at the Havana Club.

Dean would smile his easy smile and say something smooth about fate and timing. Jerry would launch into an exaggerated story, making it bigger and funnier and less true with every telling. But the truth was simpler and stranger than either of their versions. The truth was that Dean Martin’s career was ending. Jerry Lewis’s career hadn’t started.

And in a moment of desperation and chaos, they found something neither of them had been looking for. Not fame, not yet. Connection, the feeling of another person understanding exactly what you need in the moment you need it. They stayed together for 10 years, Martin and Lewis. They made 17 films, released countless records, became one of the most successful comedy teams in entertainment history.

And it all started because a 20-year-old comedian with nothing to lose climbed onto a stage where he didn’t belong. and a 28-year-old singer with everything to lose decided not to push him off. The partnership eventually ended in 1956 with lawyers and hurt feelings and years of silence between them. But that’s a different story.

This story is about the moment before all that. The moment when two people who didn’t know each other found a rhythm together, found a way to be bigger together than they could ever be alone. If you enjoyed spending this time here, I’d be grateful if you’d consider subscribing. A simple like also helps more than you’d think.

Dean Martin went on to solo success that eclipsed what most people thought he was capable of. Jerry Lewis became a legend of physical comedy, a director, an icon. But neither of them ever quite recaptured what they had in those early years. those nights at the Havana Club and the clubs that came after when everything was new and possible and the only thing that mattered was making it to the end of the show without falling apart.

If you want to hear what happened the night Frank Sinatra walked into one of their shows and changed everything again, tell me in the comments.

News

Why General Patton Ordered His Jeeps to Have “Wire Cutters”

Why General Patton Ordered His Jeeps to Have “Wire Cutters” March 25th, 1945. Palm Sunday, the city of Aken, Germany….

Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy Johnson’s Wife in Public — His Photo Album Made the ENTIRE Mafia RETREAT…

Mobster SLAPPED Bumpy Johnson’s Wife in Public — His Photo Album Made the ENTIRE Mafia RETREAT… June 8th, 1962. 2:47…

A Gun Clicked in Lucky Luciano’s Face — What Happened After Became Legend

A Gun Clicked in Lucky Luciano’s Face — What Happened After Became Legend The humiliation didn’t end with the click….

When Audrey Hepburn’s Maid Discovered the Horrible Truth

When Audrey Hepburn’s Maid Discovered the Horrible Truth There’s a moment in 1979 when Audrey Hepern, age 50, is sitting…

Audrey Hepburn’s Final Love Was Married To Merle Oberon Who Was Dying.

Audrey Hepburn’s Final Love Was Married To Merle Oberon Who Was Dying. January 20th, 1993. 2 a.m. Switzerland. Audrey Hepburn…

Why the FBI Couldn’t Touch Pittsburgh’s Mafia for 40 Years

Why the FBI Couldn’t Touch Pittsburgh’s Mafia for 40 Years John Sebastian Loraca was born in Sicily in 1901, entering…

End of content

No more pages to load