Experts Called His 75mm Cannon “Suicide” — Until It Sunk A Destroyer

At 9:17 a.m. on a humid morning in early 1942, a flight of B7 flying fortresses opened their bomb bay doors over the Solomon Sea. They were flying at 20,000 ft, perfect textbook altitude, according to the Army Airore manual. Below them, a convoy of Japanese destroyers cut through the blue water like jagged knives.

The American bombarders peered through their Nordon bomb sites, devices so secret and complex they were rumored to be able to drop a pickle into a barrel from four miles up. The mathematics were calculated. The drift was adjusted. The release levers were pulled. Dozens of 500 lb high explosive bombs whistled down through the clouds. The crews waited 40 long seconds for the impact, expecting to see the convoy disintegrate in columns of fire and steel. They hit absolutely nothing.

The ocean erupted in white geysers of foam 200 yd away from the nearest Japanese ship. The destroyers didn’t even break formation. Their captains simply watched the bombs fall, ordered a hard turn to port [music] or starboard, and let the American explosives splash harmlessly into the empty Pacific. It was humiliating.

It was a mathematical impossibility [music] that was happening every single day. The army had spent millions of dollars convincing the world that highaltitude precision bombing was the future of warfare. But out here in the mess of the Southwest Pacific, the future was looking useless. The pilots flew back to their bases in New Guinea, tired, angry, and empty-handed, while the Japanese Tokyo Express continued to deliver thousands of troops and tons of supplies to the jungle front lines without a scratch on their paint.

This failure was the nightmare that welcomed General George Kenny when he arrived to take command of the Allied Air Forces in the Southwest Pacific. Kenny was not a man who cared about manuals or polished brass. He was a short, aggressive, harsh spoken aviator who looked more like a mechanic than a general.

He walked with a strut and talked like he was trying to start a fight in a bar. When he landed in Australia, he found an air force that was demoralized and broken. The maintenance crews were scavenging scrap metal to keep planes flying. The pilots were flying suicide missions with tactics [music] that didn’t work, and the Japanese Navy was running circles around them.

Kenny looked at the reports of the high altitude bombing raids and threw them in the trash. He knew that trying to hit a destroyer moving at 30 knots from 20,000 ft was like standing on the roof of a skyscraper [music] and trying to drop a marble into a coffee cup that was being dragged by a sprinting cat. The problem was the physics of the engagement.

A bomb dropped from high altitude takes nearly a minute to reach sea level. In that minute, a destroyer captain can look up, see the bay doors open, and move his ship half a mile in any direction. The Japanese knew this. They mocked the American bombers. They didn’t even bother to scatter. They just danced out of the way and let the ocean swallow the American tax dollars.

Kenny realized that if he wanted to stop the bleeding in the Pacific, he had to stop those ships. And if he wanted to stop those ships, he had to get lower. He needed to get down into the spray and the salt right in the face of the enemy. But he didn’t just want to strafe them with machine guns. Machine guns were for shooting down flimsy airplanes.

They would bounce off the steel hull of a destroyer like gravel thrown at a tank. Kenny needed artillery. He needed a weapon that could punch through a boiler room or rip the bridge off a warship. He started looking around his hangers for a solution. He saw the B-25 Mitchell bomber. It was a sturdy twin engine medium bomber, reliable and tough, but it was designed to drop bombs, not fight like a battleship.

Then he looked at the ground equipment. He saw the standard army 75 mfield gun. It was a monster of a weapon, a descendant of the famous French 75 from the First World War. It fired a 15-lb shell that could smash through concrete bunkers and light tanks. It was heavy, violent, [music] and designed to be bolted to the ground or mounted inside a 30-tonon Sherman tank.

It was absolutely not designed to be bolted inside the nose of an airplane. The idea was insanity. Putting a 75 cannon into a B-25 was like trying to mount a howitzer on a surfboard. The weight alone was a nightmare. The cannon weighed nearly a,000 lb. The ammunition weighed hundreds more. And then there was the recoil.

When a 75 mechan fires, it generates a recoil force that feels like a car crash. On the ground, the gun digs its spades into the dirt to absorb the shock. In a tank, the 30 tons of steel absorb the kick. In an aircraft, there is nothing to absorb the shock except the aluminum frame and the rivets holding the wings together. The engineers at North American Aviation, the company that built the B-25, looked at Kenny’s request and thought he had lost his mind.

They pulled out theirslide rules and ran the stress calculations. The numbers came back in bright red ink. They told Kenny that the recoil from the cannon would tear the nose off the aircraft. They said the shock wave would shatter the glass in the cockpit and potentially knock the pilot unconscious. They claimed that even if the plane held together, the sudden deceleration from firing the gun would cause the aircraft to stall in midair, causing it to drop out of the sky like a stone.

They wrote long detailed reports explaining [music] exactly why this was impossible. They used words like structural fatigue, airframe stress limits, and catastrophic failure. They essentially told the general that he was asking them to build a suicide box that would kill his own pilots faster than the Japanese could. They suggested he stick to bombs and machine guns, the things the plane was actually designed to carry.

Kenny didn’t care about their slide rules. He cared about the Japanese destroyers that were currently unloading troops on Guadal Canal in New Guinea. While his bombers missed them from the stratosphere, he looked at the engineers and gave them a simple order. Throw the manual away. [music] He wasn’t asking for permission.

He was telling them what was going to happen. He wanted the glass nose of the B25 removed. He wanted a solid metal nose installed to house the massive breach of the cannon. He wanted the cockpit rearranged so a loader could stand next to the pilot and shove artillery shells into the gun by hand while the plane was bouncing through turbulence at 200 mph.

The conflict between the experts in California and the warriors [music] in the Pacific reached a boiling point. The engineers viewed the aircraft as a precision machine, a delicate balance of lift and drag and thrust. Kenny viewed the aircraft as a tool to kill the enemy. and if he had to break the tool to get the job done, he would break it.

He argued that the B-25 was overengineered, that it was tougher than the designers gave it credit for. [music] He told them that in the jungle, his mechanics were patching holes with soup cans and bailing wire, and the planes were still flying. He was betting the lives of his men on the idea that a chaotic, desperate innovation could beat the carefully calculated perfection of the factory blueprints.

The experts finally relented, but not because they agreed. They relented because Kenny was a general with the full weight of the war effort behind him. They agreed to build a prototype, but the skepticism was thick enough to cut with a knife. They called it the B-25G model. To the engineers, it was an aberration, a Frankenstein monster that violated every rule of aeronautical design.

To the pilots, it was a terrifying rumor. They heard whispers about a plane that carried a tank gun. They joked that the plane would fly backward when they pulled the trigger. They called it the flying artillery. But beneath the jokes, there was a real fear. They were being asked to fly straight at a destroyer, a ship armed with dozens of anti-aircraft guns, and fire a single shot from a weapon that might rip their own wings off.

Kenny sent the order to modify the first batch of planes. He wasn’t waiting for the perfect test results. He needed the weapons now. The factory floor at North American Aviation became a scene of confused urgency. Beautiful streamlined glass noses were chopped off. Heavy steel cradles were bolted into the fuselages. The delicate balance of the aircraft was completely destroyed.

They had to add hundreds of pounds of lead weight to the tail just to keep the plane from tipping forward onto its nose when it was parked on the runway. It was ugly. It was heavy. It handled like a dump truck. [music] And nobody, not even Kenny, knew for sure what would happen when the pilot pulled the trigger for the first time in combat.

The stage was set for a disaster or a revolution. The transformation of the B-25 from a medium bomber into a flying gunship did not happen in a sterile laboratory with white-coated scientists gently turning screwdrivers. It happened in sweat- soaked hangers in Townsville and Port Morsby where mechanics stripped the aircraft down with the brutality of a chop shop operation.

The beautiful glazed greenhouse nose which offered the bombardier a panoramic view of the target was unceremoniously sawed off. In its place, the crews installed a blunt, ugly snout made of sheet metal. It looked like the plane had been punched in the face, and the swelling hadn’t gone down. Inside this metal snout sat the M4 cannon, a weapon so large that the pilot could practically reach out and pat the breach.

The installation was a nightmare of plumbing and steel. The recoil mechanism alone, a complex system of hydraulic fluid and heavy springs, took up half the forward compartment. This system was the only thing standing between the pilot and a broken neck. It was designed to absorb the 21-in kick of the barrel, soaking up the violence ofthe explosion, so the airframe didn’t have to.

To accommodate this monster, the interior of the plane had to be gutted. The navigator’s station, usually a place of maps and quiet calculation, was deleted entirely. The bombardier, the man who was supposed to be the star of the show with his Nordon bomb site, was fired. In their place stood a new crew member with the most terrifying job description in the Army Airore, the Canoneer.

This wasn’t a job for a small man. The canineer had to stand in a cramped, vibrating tunnel of aluminum right next to the pilot’s knees and wrestle with 15lb artillery shells. There was no automatic loader. There was no robotic arm. There was just a man, a rack of high explosive shells, and a cannon that smelled of hot grease and cordite.

He had to physically shove the shell into the brereech, slam the block closed, tap the pilot on the shoulder to signal ready, and then brace himself against the wall while the gun fired mere inches from his head. The engineers back in California had warned that the center of gravity would be ruinous. They were partially right.

When the mechanics finished the first modification, the plane was so noseheavy that the tail wheel lifted off the [music] tarmac. It looked like a sniffing dog. To fix it, they didn’t use sophisticated aerodynamic counterbalances. They just bolted lead bars into the tail section until the plane sat flat again. It was a crude backyard solution that added even more weight to an already sluggish aircraft.

When the test pilots climbed in for the first taxi runs, they reported that the plane handled like a dump truck with wings. It was heavy, unresponsive, and groaned under the strain of the artillery piece. The sleek, agile bomber was gone. In its place was a flying tank that the crews affectionately and nervously nicknamed the Lil Monster.

General Kenny didn’t care about the handling characteristics. He cared about the trigger pull. The first live fire test was the moment of truth that would either vindicate him or end his career in a court marshal for negligent homicide. The test plane rumbled down the runway, using nearly every foot of asphalt to heave itself into the humid air.

It climbed slowly, struggling for altitude. The target was a small, uninhabited coral reef off the coast. The pilot lined up the nose, fighting the sluggish controls. Inside the cockpit, the tension was thick enough to choke on. The canineer slammed the first shell home. “Gun ready!” he shouted over the roar of the right cyclone engines.

“The pilot put the reef in his iron sights. There were no fancy optics here, just a simple postandring sight bolted to the dashboard and squeezed the release on the control yolk. The sensation was indescribable. It wasn’t just a sound. It was a physical event. The entire airframe shuddered as if it had flown into a brick wall.

The plane’s forward momentum seemed to pause for a split second, arrested by the sheer physics of Newton’s third law. Inside the cockpit, a cloud of acurid white gun smoke filled the air, momentarily blinding the crew. The noise was a deafening thump that rattled the pilot’s teeth. But then the smoke cleared. The wings were still attached. The rivets held.

The glass didn’t shatter, and down on the reef, a massive plume of water and pulverized coral erupted exactly where the nose had been pointing. The recoil hadn’t stalled the engines. The structural integrity hadn’t failed. The California engineers had been wrong. You could put a field gun in a plane, provided you were crazy enough to fly it.

With the concept proven, the Green Dragons, the 405th Bomb Squadron, began the arduous process of learning how to fight with this new weapon. It required a complete rewriting of the pilot’s manual. A bomber pilot is trained to fly straight and level to be a stable platform for the falling ordinance.

A gunship pilot had to be a fighter. The 75 mechan was fixed forward. It couldn’t turn or pivot. To aim the gun, you had to aim the entire plane. This meant the pilot had to dive the massive bomber directly at the target, ignoring the anti-aircraft fire and hold the nose steady until he was close enough to guarantee a hit. They called it bore sighting.

It was a game of chicken played at 200 mph. The effective range of the cannon was technically thousands of yards, but in the chaotic reality of combat, the pilots found they had to get close, suicidally close. 1,000 yd, 800 yd, close enough to see the rivets on the enemy ship. The training was intense. [music] Pilots practiced diving on old shipwrecks, learning the terrifying rhythm of the attack run.

Dive, stabilize, fire, recover from the recoil, reload, fire again. The rate of fire was slow, maybe three or four rounds in a single pass if the canoneer was fast and didn’t pass out from the G-forces. This wasn’t a machine gun that sprayed bullets. This was a sniper rifle. [music] You had one shot, maybe two, to hit a moving target while yourown plane was bouncing through turbulence.

If you missed, you had to loop around and try again, exposing your belly to the enemy guns. The crews learned to coordinate like a football team. The pilot focused on the flying. The co-pilot managed the engines and called out ranges. The cantoner became a rhythm machine. Load, breach, clear, fire. Load, [music] breach, clear, fire.

They practiced until their hands were raw and the cockpit floor was covered in heavy brass casings. The first victims of this new weapon were not the mighty destroyers, but the coastal barges and luggers that the Japanese used to ferry supplies between the islands. These were small wooden or rusting steel vessels, usually armed with a single machine gun.

The B-25s found them creeping along the coastline at dawn. The engagement was almost unfair. A standard bomb would often punch right through a wooden barge without detonating, leaving a neat hole, but failing to sink it. The 75 Mahai explosive shell was different. When the first round hit a supply barge near Lei, the result was absolute disintegration.

The shell smashed into the hull and detonated inside the cargo hold. The barge didn’t just sink. It vanished in a shower of splinters and burning fuel. The pilots returned to base with eyes wide. They hadn’t [music] just damaged the enemy. They had erased them. Word spread quickly through the squadrons. The suicide box was actually a hammer.

The skepticism evaporated, replaced by a hungry eagerness. Crews started painting names on their gunships. Aggressive names like Ominous 7bang, Sunday Punch, and Dirty Dora. They mounted additional machine guns in the nose, surrounding the cannon with 450 caliber heavy machine guns.

Now, when a pilot pulled the trigger, he wasn’t just firing artillery. He was unleashing a storm of lead that could shred the deck crews before the cannon delivered the knockout blow. They called it the commerce destroyer configuration. It was a weapon system designed for one purpose, to hunt ships, but hunting barges was target practice.

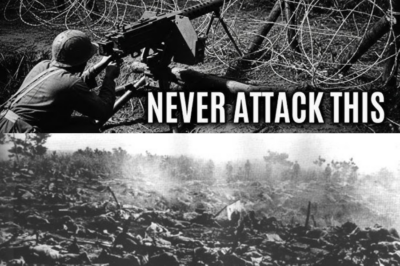

The real test, the one General Kenny had built this Frankenstein monster for, was the Tokyo Express. The Japanese Navy was still running destroyers down the slot, arrogant and untouched. These weren’t defenseless barges. A Japanese destroyer was a 300 ft spear of steel, bristling with 25mm autoc cannons and 5-in dualpurpose guns. Its crew was disciplined, battleh hardened, and experts at shooting down aircraft.

They had watched American bombers fail for months. They had no respect for the B-25. To them, a medium bomber at low altitude was just a large target, a slowmoving duck waiting to be plucked from the sky. The escalation began in late 1942. The Japanese high command, frustrated by the slow attrition of their barges, decided to commit a major convoy to reinforce their garrisons on New Guinea.

They assembled a fleet of fast transports protected by the Amitsukazi and her sister destroyers. These were the wolves of the ocean ships that had fought the US Navy to a standstill at Guadal Canal. They were fast, maneuverable, and heavily armed. They steamed south with the confidence of apex predators, assuming their speed would protect them from submarines, and their flack guns would protect them from the high altitude bombers.

They didn’t know the rules of the game had changed. They didn’t know that a squadron of B-25s was waiting on the tarmac, engines warming up with artillery shells stacked in the racks. On the morning of the interception, the weather was patchy with low clouds hugging the water, perfect cover for a low-level ambush. Major Edens, leading the flight, checked his instruments.

His plane, heavily laden with fuel and ammunition, felt sluggish in his hands. He looked over at his co-pilot, then back at the canineer, who gave a nervous thumbs up. They were hunting giants today. The chatter on the radio was minimal. The pilots knew the stakes. If the engineers were right, the first hit from a destroyer’s main gun would turn their aluminum planes into confetti.

If Kenny was right, the 75 mechan would crack the destroyers open like tin cans. As they broke through the cloud layer, the convoy appeared on the horizon. Gray shapes cutting white wakes through the dark water. The destroyers spotted them immediately. Black puffs of flack began to blossom in the sky long before the planes were in range.

The Japanese captains ordered their ships to turn, presenting their broadsides to bring maximum firepower to bear. It was the standard defense, a wall of steel thrown into the sky. But the B-25s didn’t climb. They didn’t open bomb bay doors. They dropped. They pushed their yolks forward and descended until they were skimming 50 ft above the waves.

Their propellers kicking up spray. They were flying straight into the teeth of the enemy fire. closing the distance at 300 ft per second. The experts had said this was suicide. The pilots were about to find out if it was actually murder. Thedistance between the B-25 and the Japanese destroyer Amitsukazi closed at a relative speed of nearly 400 mph.

From the bridge of the destroyer, the Japanese captain watched the American bomber through his binoculars with a mixture of confusion and professional disdain. He had seen this maneuver before. It looked like a standard torpedo run. American torpedo planes always came in low and slow, trying to drop their fish into the water so they could run straight and true.

The counter tactic was elementary naval doctrine, turn the ship into the attack, by pointing the sharp bow of the destroyer directly at the plane. [music] He would present the smallest possible target, making the torpedo pass harmlessly down the side of the hull. He barked the order to the helmsman. The 300 ft warship leaned hard to starboard, carving a massive white arc in the ocean as it swung its nose around to face the intruder.

But as the destroyer turned, the captain noticed something wrong. The American plane wasn’t dropping a torpedo. It wasn’t pulling up. It wasn’t weaving to avoid the anti-aircraft fire. It was flying in a straight, terrifying line, nose down like a hawk diving on a field mouse. The B-25 wasn’t trying to flank the ship.

It was charging it headon. This was madness. By flying directly at the bow, the American pilot was flying straight into the barrel of the destroyer’s forward 5-in gun and the dual 25mm autoc cannons mounted on the bridge wings. It was a game of chicken between a 20,000lb aluminum airplane and a 2,000 ton steel warship.

The Japanese gunners [music] opened fire. Tracers lashed out from the ship like fiery whips, cracking the air around the cockpit. The sky became a chaotic web of black smoke puffs and screaming metal. Inside the cockpit of the lead B-25, the world shrank down to the size of the ring sight mounted on the dashboard. The pilot gripped the yolk with white knuckles, fighting the turbulence and the instinct to flinch.

Every tracer that zipped past the canopy was a reminder of how thin the aluminum skin really was. A single hit from the destroyer’s main gun would vaporize the plane instantly, but the pilot couldn’t dodge. The 75mm cannon was bolted to the floor. To aim the gun, he had to aim the plane. He had to hold the aircraft steady in the face of a wall of steel, ignoring the explosions, ignoring the fear, and trusting the math.

He was the targeting computer. [music] His hands, his eyes, and his nerve were the only guidance system the weapon had. At 1,200 yd, the pilot squeezed the trigger on the control column, not for the cannon, but for the machine guns. 450 caliber heavy machine guns mounted in the nose erupted simultaneously.

The sound was a jackhammer roar that vibrated [music] through the floorboards. Streams of armor-piercing incendiary bullets poured out of the nose at a rate of 50 rounds per second. They walked across the water like a chainsaw, kicking up a line of white splashes that raced toward the destroyer. The impacts hit the ship’s bow and swept backward toward the bridge.

The bullets hammered against the steel plating, sparking and ricocheting, but they weren’t meant to sink the ship. They were meant to blind it. The hail of leads smashed the glass of the bridge windows and shredded the unprotected anti-aircraft crews on the deck. The Japanese gunners, who moments ago had been firing with disciplined precision, were forced to duck for cover behind their gun shields. The flack faltered.

That was the opening. The pilot held the dive. The destroyer filled the entire windshield. A gray mountain of steel growing larger by the millisecond. 800 yardds, 700 yardds. The cantoner in the tunnel tapped the pilot’s shoulder. The gun was hot. The breach was closed. The shell was live.

The pilot made a micro adjustment on the yolk, lifting the nose just a fraction of a degree to aim for the waterline right beneath the forward turret. He stopped breathing. He squeezed the cannon trigger. The B-25 stopped in midair. That’s what it felt like. The recoil of the 75mm cannon delivered a punch of kinetic energy equivalent to a collision with a brick wall.

The plane shuddered violently from nose to tail. Dust and dirt from the floorboards floated up into the air. The smell of burning propellant flooded the cockpit, sharp and acidic. For a split second, the pilot was blind, [music] the view obscured by the massive cloud of white smoke that belched from the muzzle. But the physics of the shell were already at work.

The 15-lb high explosive projectile left the barrel at 2,000 ft per second. It crossed the 600 yd of open ocean in less than a second. It didn’t skip off the water. It didn’t bounce off the armor. It struck the steel hull of the destroyer just above the water line with the force of a freight train. The impact was catastrophic.

A destroyer’s hull is designed to stop machine gun bullets and shrapnel, not artillery shells. The 75mm round punched through the half-in steelplating as if it were wet cardboard. It didn’t detonate on the outside. The fuse was set with a split-second delay. The shell smashed through the outer skin, tore through a bulkhead, and exploded deep inside the ship’s machinery spaces.

The blast shredded steam pipes and electrical conduits. It turned the interior of the forward compartment into a blender of shrapnel and high-press steam. On the bridge, [music] the Japanese officers felt the ship lurch as if it had run a ground. They didn’t understand what had hit them. It felt like a torpedo, but there was no wake.

It felt like a mine, but they were in deep water. They never imagined they had just been shelled by an airplane. The B-25 roared over the destroyer’s masts so close the rear gunner could look down and see the panic on the deck. As the pilot pulled back on the stick to climb away, the cantoner was already moving.

This was the hardest part of the job. The aircraft was banking hard, pulling G-forces that made his body weigh twice its normal limit. He had to keep his balance on the vibrating metal floor, reach into the rack, and pull out another 15-lb shell. He wrestled the heavy brass casing into the brereech, his muscles straining against the G-force.

[music] He slammed the brereech block closed with a metallic clang that echoed through the fuselage. “UP!” he screamed into the intercom. The gun was ready again. The pilot brought the plane around in a tight, aggressive turn. [music] He looked back at the target. The destroyer wasn’t maneuvering anymore.

Smoke was pouring from a jagged hole in the bow. The ship was listing slightly to port. The hit had damaged something critical. Maybe a boiler. Maybe the steering gear. The Predator was wounded. The pilot lined up for a second pass. This time there was no surprise. [music] The Japanese sailors were scrambling to get their guns back in action, but the fear had set in.

They weren’t shooting at a fragile bird anymore. They were shooting at a flying tank. On the second run, the pilot aimed for the stern. He wanted to knock out the propulsion. He repeated the deadly rhythm, the strafing run to suppress the deck, the hold, the trigger squeeze. The cannon barked again.

The recoil shook the airframe. The second shell struck the aft section of the destroyer near the depth charge racks. The explosion was different [music] this time, a secondary detonation. The shell had ignited something volatile. A massive fireball erupted from the rear of the ship, blowing debris high into the air. The shock wave rippled through the water, visible from the air as a dark ring expanding outward.

The destroyer shuddered and began to slow. The white wake behind it once a frothy trail of speed faded to a turbulent swirl. The great ship was dead in the water. The rest of the squadron descended like vultures. They didn’t need the cannons anymore. They switched to skip bombing. They came in low, releasing 500 lb bombs that skipped across the water surface like flat stones on a pond.

The bombs slammed into the side of the crippled destroyer, detonating on contact with the hull. The Amitsukazi groaned under the assault. The steel [music] plates buckled. The ocean rushed in. The proud warship, a vessel that had terrorized the South Pacific for a year, began to settle into the water. It hadn’t been sunk by a battleship.

It hadn’t been sunk by a submarine. It had been beaten to death by a group of modified bombers that the experts said would never fly. As the B-25s turned for home, the crews looked back at the burning wreck. The radio chatter was ecstatic. They were shouting, laughing, releasing the adrenaline that had been built up during the terrifying approach.

But beneath the celebration, there was a profound realization. The dynamic of the Pacific War had just shifted on its axis. For 2 years, the surface ship had been the king of the ocean, vulnerable only to other ships or lucky dive bombers. Now, the equation was broken. A single airplane armed with a weapon pulled from a tank could hunt down and kill a warship.

The Japanese Navy could no longer hide behind their flack [music] curtains. They could no longer rely on speed. The ocean had become a very small, very dangerous place. Back in the cockpit, the pilot flexed his hands to get the blood flowing again. His flight suit was soaked with sweat. The floor was littered with hot brass casings that rolled around with every turn.

The nose of the plane was covered in soot from the muzzle blasts. The aircraft handled even worse now. Lighter by the weight of the ammunition, but still aerodynamically ruined. But the pilot didn’t care about the drag or the heavy nose or the lack of a navigator. He padded the [music] dashboard. The suicide box had worked.

The engineers in California could keep their slide [music] rules. Out here in the salt and the smoke, they had found the answer. They had turned the B-25 into the ultimate can opener. When Major Edensand his flight of battered B-25s touched down at Port Morsby, the aircraft didn’t look like the same machines that had taken off hours earlier.

The pristine aluminum skins were stained black with soot from the muzzle blasts. The paint on the nose cones was blistered from the heat of the cannon fire. Inside the cockpits, the floorboards were littered with heavy brass shell casings that rolled back and forth with every bump on the runway, chiming like church bells.

The crews climbed out of the hatches with shaky legs, their flight suits soaked through with sweat, their ears ringing from the concussive force of the 75mm guns. They looked like men who had just gone 12 rounds in a boxing ring, but their eyes were alive with a frantic electric energy. They hadn’t just survived a suicide mission.

They had rewritten the laws of physics. The debriefing room was usually a somber place where pilots reported missed targets and heavy flack, but today it was a scene of chaotic vindication. The gun camera footage told the story better than any written report could. Grainy black and white film showed the impossible truth, the massive splash of the cannon shell hitting the water, the violent shutter of the impact on the destroyer’s hull, and the subsequent explosion that ripped the ship apart.

General Kenny looked at the photos of the burning Amitsukazi and smiled. It was the smile of a man who had bet his entire reputation on a stupid idea [music] and won. He ordered the photos to be developed immediately and sent back to the United States. He wanted them on the desk of every engineer at North American Aviation who had told him the recoil would tear the wings off.

The message was clear. The wings were fine, but the Japanese Navy was in big trouble. The success of the flying artillery changed the manufacturing priorities of the war overnight. The engineers in California, the ones with the slide rules and the stress charts, stopped arguing and started building. The B-25G model went into full production, followed quickly by the even more heavily armed H model.

The factory floors that had once been skeptical were now churning out these monsters as fast as they could weld the steel noses on. They stopped trying to make the plane aerodynamic and started trying to make it lethal. They added more armor plating around the cockpit to protect the pilots from the intense return fire they faced at mass height.

They upgraded the recoil mechanisms. They turned the B-25 from a medium bomber into the premier street fighter of the Pacific theater. For the Japanese captains navigating the Bismar Sea and the straits around New Guinea, the ocean had become a terrifying place. They had spent the early years of the war fearing dive bombers and submarines, threats they could see coming or maneuver against.

But this new weapon was different. It was a psychological terror. There was something deeply unnatural about being shelled by an airplane. It broke the established rules of warfare. Convoys that used to steam confidently in broad daylight began to hide in the shadows of the islands, moving only at night or in bad weather. The arrogance of the Tokyo Express evaporated.

The destroyers that had once laughed at high altitude bombers now turned and ran the moment they saw a twin engine silhouette on the horizon. The hunters had become the hunted. The peak of the cannon’s career came during the battle of the Bismar Sea where the tactic of skip bombing combined with the suppressive fire of the gunships resulted in the absolute annihilation of a Japanese reinforcement fleet.

It was a massacre. The B-25s came in at deck level, their nose guns blazing, turning the troop transports into slaughterhouses before smashing them with bombs. The sea was covered in oil and debris for miles. It was the final proof that the era of the invincible surface ship was over. The B-25 had proven that air power, when applied with enough violence and ingenuity, could strangle an island nation’s supply lines completely.

However, the reign of the 75mm cannon was intense but surprisingly short-lived. As the war dragged on into 1944 and 45, technology began to catch up with General Kenny’s vision. The cannon was effective, but it was difficult to use. It required a pilot with nerves of steel and the aim of a sniper. It required a human loader to wrestle heavy shells in a moving aircraft.

It was a brute force solution from a mechanical age. The replacement arrived in the form of the high velocity aircraft rocket or HVAR. These were 5-in rockets that could be mounted under the wings of almost any fighter or bomber. They didn’t have the recoil of the cannon. They didn’t need a loader. A pilot could fire a salvo of eight rockets with the push of a button, delivering the same destructive power as a broadside from a destroyer.

The rockets were easier, lighter, and more efficient. The massive M4 cannon began to look like a dinosaur. The later models of the B-25 replaced the singlebig gun with a solid nose packed with eight, sometimes 1250 caliber machine guns. It became a flying buzzsaw capable of shredding a target with volume of fire rather than a single knockout punch.

The pilots missed the visceral power of the lil monster, the feeling of the plane stopping in midair when they pulled [music] the trigger. But they couldn’t argue with the efficiency of the rockets. The cannon had done its job. It had bridged the gap between the failure of high alitude bombing [music] and the arrival of the rocket age.

It had saved the campaign in New Guinea when nothing else could. By the time the war ended, the B-25 gunships were being scrapped or sold off. The massive cannons were unbolted and thrown into piles of surplus metal. General Kenny moved on to other commands, his reputation cemented as the man who revolutionized air warfare in the Pacific.

The pilots went home to become accountants and car salesmen, rarely speaking about the days when they flew tank guns into the faces of destroyers. The flying artillery faded into a footnote of aviation history, a strange experiment that people assumed was [music] just a desperate improvisation. But the idea didn’t die. The concept of a heavy gunship, a plane that orbits a target and rains down heavy fire, was buried in the archives, waiting for the next war to dig it up.

20 years later in the jungles of Vietnam, the concept was reborn. The Air Force took an old cargo plane, the C-47, and mounted gatling guns in the side doors. They called it Spooky. It was the direct spiritual descendant of Kenny’s B25. Then came the AC-130 Spectre, a massive transport plane armed with 40mm cannons and eventually a 105 mm howitzer, the same caliber of field artillery that Kenny had dreamed of using.

The AC-130 became the ultimate realization of the idea. A flying battleship that could circle a target and destroy it with precision artillery fire from the sky. Every time a Spectre gunship fires a shell today, it is echoing the thunder of those first, clumsy, terrifying shots fired by the B-25s over the Bismar Sea. The engineers said it was impossible.

They said the physics wouldn’t work. They said the recoil would destroy the plane. But history is rarely written by the people who say it can’t be done. It is written by the people who are too stubborn to listen. It is written by men like General Kenny who looked at a manual and saw only a suggestion. It is written by men like Major Edens who looked at a destroyer and decided to charge it headon.

They proved that sometimes the smartest solution is the one that looks the stupidest on paper. They proved that with enough courage and enough gunpowder, you can make a bomber do the job of a battleship. We rescue these stories to ensure that the Green Dragons and their rattled, smokefilled cockpits don’t disappear into silence.

We tell them because they remind us that innovation isn’t always about high-tech microchips or sleek aerodynamics. Sometimes innovation is just a big gun, a heavy hammer, and the will [music] to use it. If you enjoyed this deep dive into the insane engineering of World War II, do me a favor and hit that like button right now.

It tells the algorithm that real history matters. Check your subscription status. Make sure you’re locked in so you don’t miss the next episode where we uncover another forgotten machine of war. And leave a comment below. Would you have been crazy enough to stand in that nose and load the shell? I’ll see you in the next

News

LeBron James’ Agent Drops Truth Bomb on Whether This Could Be His Last Season

LeBron James’ Agent Drops Truth Bomb on Whether This Could Be His Last Season January 8, 2026, 11:58pm EST 38 • By Debmallya Chakraborty…

Draymond Green and Dennis Schroder Get Into Heated Jawing Match All the Way Down the Floor [VIDEO]

Draymond Green and Dennis Schroder Get Into Heated Jawing Match All the Way Down the Floor [VIDEO] January 10, 2026,…

John Wayne Saw a Man Alone at a Military Funeral in the Rain and Quietly Changed His Life

John Wayne Saw a Man Alone at a Military Funeral in the Rain and Quietly Changed His Life November 1953,…

How One Mechanic’s “Stupid” Wire Trick Made P-38s Outmaneuver Every Zero

How One Mechanic’s “Stupid” Wire Trick Made P-38s Outmaneuver Every Zero At 7:42 a.m. on August 17th, 1943, Technical Sergeant…

In 1942, Japan Attacked America’s Henderson Field — A Catastrophic Mistake

In 1942, Japan Attacked America’s Henderson Field — A Catastrophic Mistake Japan didn’t lose Guadal Canal because they were outnumbered….

Eisenhower’s Real Reaction When Patton Turned His Army 90° in 48 Hours

Eisenhower’s Real Reaction When Patton Turned His Army 90° in 48 Hours The most important Allied victory of 1,944 didn’t…

End of content

No more pages to load