German Submarine Tore His Ship Apart — This Captain Sailed 800 Miles With a Massive Hole in the Hull

At 1955, on February 22nd, 1943, Commander James Hersshfield stood on the bridge of USCGC Campbell, watching his radar operator track a contact at 4,600 yd in the black North Atlantic. 40 years old, 20 years Coast Guard service. Zero Yubot sunk. 19 German submarines had surrounded convoy 166.

14 merchant ships would sink before the Wolfpack withdrew. Campbell was a Treasury class cutter, 327 ft long, 20.5 knots maximum speed. She’d been escorting convoys since December 1941. Her crew of 200 men had survived 2 years of Atlantic duty. They’d rescued drowning sailors, dodged torpedoes, dropped depth charges on contacts that vanished into the deep.

They’d never killed the submarine. Hersshfield had joined the Coast Guard in 1922. He’d chased rum runners during Prohibition, commanded patrol boats, worked his way up through peaceime ranks. When war came, the Coast Guard transferred to Navy control. Hersshfield got Campbell. The Atlantic got deadlier. February 1943 was the worst month of the Battle of the Atlantic.

120 ships sank worldwide, 82 of them in the Atlantic alone. German Admiral Carl Donuts had deployed over 100 Ubot in the mid ocean gap, that 600-m stretch beyond the range of land-based aircraft where Wolfpacks operated with near impunity. Convoy O 166 had departed Liverpool on February 11th.

63 ships, merchant vessels carrying supplies from Britain to North America. Campbell and her sister cutter Spencer led the escort. Five corvettes from Canada and Britain provided additional protection. The Polish destroyer Bersa joined them midc crossing. Eight escorts, 63 merchants, 19 yubot hunting them. The convoy had sailed through 8 days of northwesterly gales.

Ships scattered, lost formation, became easy targets. On February 20th, U 604 spotted them. The Wolfpack closed in. February 21st started with a torpedo. U332 hit the Norwegian freighter Stigstad at dawn. She went down with her cargo. Then U92 struck twice. The British Empire trader took a torpedo at 8:32 in the evening. 2 hours later, the Norwegian tanker NT Nielsen Alonzo exploded.

Campbell raced to the rescue. Hersshfield brought his cutter alongside the burning wreckage. 50 Norwegian sailors were in the water. North Atlantic in February. Water temperature 36 degrees Fahrenheit. Survival time 15 minutes maximum. Campbell’s crew pulled 50 men from the sea. Every single one alive. Hersshfield ordered his helmsman to return to Neielson Alonzo.

The captain hadn’t dumped his confidential materials. They had to be destroyed or recovered. Campbell came within one mile of the sinking ship. A torpedo wake crossed their stern, missed by yards. The explosion threw water across Campbell’s deck. A yubot had fired at them during the rescue. Hersshfield ordered depth charges dropped, then turned back to the convoy.

He’d saved 50 lives, lost track of how many ships were burning on the horizon. Throughout February 21st and into the 22nd, Campbell attacked multiple yubot contacts, dropped depth charges, forced submarines to dive, damaged at least two badly enough they had to withdraw. But every time Campbell chased one yubot, others slipped through.

Torpedoed merchant ships killed sailors. The convoy was hemorrhaging. 14 ships would be lost. Over 200 merchant seaman would die in the freezing water. The Wolfpack was winning. If you want to see how this battle ended, please take a moment to like this video. It really helps us continue bringing you forgotten World War II stories.

And please subscribe. Back to Hersfield. At 1955 on February 22nd, Campbell’s radar picked up a contact at 4600 yd. Hirshfield ordered full speed ahead. The contact was moving. Surface contact. 3 minutes later, sound contact at 2400 yd, narrowing fast. 1,700 yd, 1,200 yd. At 2019, lookout spotted it. A German yubot 350 yards off the starboard bow running on the surface already damaged by depth charges from the Polish destroyer Bersa trying to escape on diesel engines.

Hersshfield had one chance, one decision, one moment to do what no Coast Guard cutter had done in this war. He could drop depth charges, fire his guns, follow doctrine, or he could do something the yubot commander would never expect, something that might sink his own ship, something that 70 years later people would call either genius or insane. Hersshfield gave the order.

Ram her full right rudder. Campbell swung hard to starboard. The Yubot was U606 type 8IC submarine 760 tons 45man crew commanded by Oberlutnut Zer Wolf Gang Heinrich. She’d already sunk three ships from this convoy. British Empire Redshank, American Chattanooga City, American Exposer, all torpedoed after sunset. Then Bersa caught her.

The Polish destroyer had hammered U 606 with depth charges, damaged her conning tower, forced her to surface. U606 couldn’t dive, could barely maneuver. Heinrich was trying to escape on diesel engines when Campbell’s radar found him. Now he had 18 seconds before impact. Campbell closed at 18 knots. Her bowwave pushed ahead.

White foam in the darkness. 300 yd. 200 150 gun crews opened fire. 20 mm cannons, 3-in 50 caliber guns. Shells slammed into U 606’s conning tower. The sound of metalhitting metal echoed across the water on Campbell starboard side. Gun four came to life. A 3in 50 caliber gun manned entirely by black crew members.

Chief Steward Lewis Ethridge was gun captain. Pointer Raymond not controlled elevation. Nine mess attendants loaded and fired. They’d trained for this moment for 2 years. Drilled in port, practiced at sea, never fired in anger. Now they fired everything they had. 32 rounds of 3-in shells. Multiple drums of 20mm ammunition.

Every gun on Campbell that could bear on target was shooting. Tracers lit the night. Shells exploded against U 606’s hull. The German crew was assembling on deck, preparing to abandon ship. None tried to man the deck gun. They knew they were finished. Campbell struck U 606 at 2021. A glancing blow down the starboard side. The impact threw men off their feet on both vessels.

Campbell’s hole scraped along U 606’s pressure hole. Metal screaming against metal. Then U 606’s bow plane caught Campbell’s hull. The diving plane was solid steel, sharp edge, designed to cut through water at depth. It cut through Campbell’s hole instead. The bow plane tore a gash 15 ft long, 8 in wide, 3 ft below the water line, right through the engine room plating.

Saltwater exploded into the compartment. The North Atlantic flooded in under pressure. Machinery spaces filled. Generators shorted. Electrical systems failed. Campbell went dark. As the cutter scraped past, her crew dropped two depth charges, 600-lb Mark 7 charges set for shallow detonation. They hit the water, sank, detonated directly under U 606’s hull.

The submarine lifted 4 ft out of the water. Her entire hole came up, visible for 3 seconds in the explosion’s light. Then she crashed back down, dead in the water. Her stern settled lower, taking on water through ruptured tanks. Her crew scrambled. Some jumped overboard. Others stayed on the conning tower, waiting for rescue. Campbell drifted past.

No power, no lights. Water pouring into her engine room. The flooding was catastrophic. Engine room crew abandoned their stations. Water rising past their knees, past their waists. The entire stern compartment was flooding. On the bridge, something hit Commander Herschfield. Shell fragments from where? Nobody knew. Campbell’s own guns.

German small arms fire. Shrapnel from somewhere in the chaos. The fragments caught him near his left ear. Cut his eyelid. Blood ran down his face. He stayed at his station below decks. Damage control team scrambled. Commander Kenneth Coward supervised the response. Engine room flooding. Generators offline. Steering compromised. They had to stop the water.

Had to save the ship. But the hole was below the water line in the engine room. While the ship was dead in the water in yubotinfested seas, U 606 was sinking 100 yards a stern. Her crew in the water yelling for help in German. Some already going under. Hypothermia kills in minutes.

Campbell was sinking too, just slower. Her engine room filled, her power gone. 19 yubot still hunting the convoy. And Campbell couldn’t move, couldn’t shoot, could barely float. Hersshfield wiped blood from his eye. His ship was dying, but U 606 was dying faster, and somewhere in the darkness, the rest of the Wolfpack was closing in. At 2035, Campbell’s motor launch hit the water.

Lieutenant Arthur Feifer commanded the boat. Six volunteers went with him. Their orders were simple. Get to U 606, take prisoners, maybe capture the submarine before she sank. U 606 was still afloat barely. Her stern was underwater. Conning tower above the surface. German crew members stood on the tower, eating sausages, drinking rum and champagne from the officer stores.

They’d opened the bottles when they knew they were finished. No point letting good liquor sink to the bottom. Feifer’s launch approached at 2100 hours. Five Germans climbed down, got into the boat, one officer, four enlisted. All shivering, all knowing they were lucky. The North Atlantic had killed most of their shipmates already.

Campbell’s crew heard more Germans in the water, yelling, screaming, dying. The cutter couldn’t maneuver to pick them up. No engines, no power, just drifting. Campbell’s volunteers threw lines, pulled men from the sea when they drifted close enough. Most didn’t make it. Hypothermia killed them before Campbell could reach them.

U 606’s commander, Oberloot Nut Wolf Gang Heinrich, was already dead, killed in Campbell’s initial barrage. His body blown off the conning tower by a 3-in shell. The warrant quartermaster had taken command, panicked, ordered everyone into the water, thought the incoming fire would slaughter anyone who stayed on deck. He was wrong.

The fire stopped, but the order killed them. 37 men from U 606’s crew of 47 died. most from exposure, some drowned, a few fromtheir wounds. The Polish destroyer Bersa arrived at 21:30. She’d been chasing another Yubot contact, heard Campbell’s radio calls, turned back. Now she circled the two dying ships, protecting them, hunting for more submarines.

Her crew pulled seven more Germans from U 606’s conning tower. They were the last survivors, the lucky ones who ignored the order to abandon ship. 12 prisoners total. Five rescued by Campbell. Seven by Bersa. 12 men out of 47. U 606 slipped under just after midnight. Her conning tower disappeared. Air bubbles broke the surface for a few minutes. Then nothing.

She settled to the ocean floor. 2200 ft down. The first yubot sunk by ramming in the Battle of the Atlantic. The first yubot kill for any United States Coast Guard cutter in World War II. But Campbell was dying, too. The engine room was flooded. Water 3 ft deep throughout the compartment rising. Every pump they had was working.

Bucket brigades formed. Men passing buckets up ladders, throwing water over the side, trying to bail out the Atlantic Ocean with buckets and desperation. It wasn’t enough. Commander Cowit organized damage control parties. They tried to patch the hole from inside. Impossible. Water pressure too high. 15 ft gash 8 in wide.

3 ft underwater. They needed to get something over it from outside. A collision mat. Heavy canvas reinforced with rope. Weighted lines to hold it in place. They started at 2035 working in darkness. Campbell had no power for flood lights. Men worked by touch, running lines under the bow, back along the hull, down to the gash.

The ship rolled in the swells, lines tangled, parted, had to be reset. It took 3 hours. 3 hours while the engine room filled while Campbell settled lower in the water. At 0200, they got the mat in place. It slowed the flooding. Didn’t stop it. Water still came through. Just less enough that pumps could almost keep up. Almost. Campbell was stable for now.

But she couldn’t move. Couldn’t defend herself. Couldn’t do anything except float and hope. Commander Hersshfield stayed on the bridge. Blood crusted on his face from the shrapnel wounds. Left ear ringing. Eyelid swollen. He refused medical attention. Refused to go below. His ship was dying. He’d stay with her until she sank or until they reached port. At 0300, Bersa came alongside.

Time to evacuate. Campbell couldn’t be saved out here. She needed a tow. A long tow. 800 miles to the nearest port. That would take days, maybe a week. The convoy couldn’t wait. Other Hubot were still attacking. Merchant ships still needed protection. Most of Campbell’s crew had to go.

Essential personnel only would stay. Damage control teams, officers, senior enlisted, men who could keep the ship afloat. Everyone else transferred to Bersa. 120 men climbed onto the Polish destroyer. The 50 Norwegian survivors from the tanker went too. Bersa took them all. Her decks were packed, men standing shouldertoshoulder.

she’d escort Campbell as long as possible, then rejoin the convoy. Campbell’s crew made one exception to the evacuation order. A small exception, four-legged, black and tan fur, white eyebrows. Sinbad stayed aboard. The dog had been Campbell’s mascot since 1937. Officially enlisted, service record, dog tags, his own hammock.

The crew believed he brought luck. believed the ship couldn’t sink while Sinbad was aboard. Commander Hersshfield agreed. Or maybe he just understood what his remaining crew needed, something to believe in, something beyond pumps and patches and prayer. Sinbad stayed. 73 men stayed. Campbell stayed afloat, barely. The North Atlantic rolled past.

Dawn came four hours away. And Campbell had no engines, no power, no way to move, just a hole in her hull, a flooding engine room, and 73 men who refused to let her sink. Dawn came at 06:30. Gray light, heavy seas. Campbell drifted without power in the middle of the Atlantic. The collision mat held.

Water still leaked through. Pumps ran constantly. Bucket brigades continued. Men worked in shifts. Four hours on, four hours trying to rest. Nobody really slept. Bersa stayed close, circling, watching. Her sonar pinged constantly, searching for submarines. Three Ubot were still operating in the area. U 604, U628, U186. All hunting, all looking for targets.

A crippled Coast Guard cutter dead in the water would be an easy kill. At 0800 on February 23rd, Bersa detected a submarine contact. She raced toward it, dropped depth charges. The contact vanished. Might have been destroyed. Might have dove deep and escaped. No way to know. She returned to Campbell. The Canadian Corvette Dofan arrived at noon.

small ship, 950 tons, but she had engines, weapons, sonar. She took over escort duty, let Bersa return to the convoy. The merchant ships needed protection. Campbell would have to wait for a tow. Commander Hersshfield stood on the bridge, still bleeding, still refusing medical attention. His executive officer brought him coffee, black, strong, the kind that had beensitting on a hot plate for 6 hours.

Hersshfield drank it. Watched the horizon. Calculated distances. 800 miles to St. John’s, Newfoundland. Nearest friendly port. Nearest shipyard. Nearest safety. At towing speed, maybe four knots, maybe less in heavy seas. That meant 8 days minimum, probably 10. Maybe 2 weeks if weather turned bad. Campbell’s engine room pumps could keep running that long.

Maybe the diesel generators were underwater, ruined, but they had emergency pumps, hand pumps, bucket brigades. They could keep her afloat as long as the hole didn’t get bigger. As long as another storm didn’t hit, as long as no Ubot found them, as long as luck held. At 1400 hours, Campbell’s crew tried something desperate.

They had portable gasoline pumps, small pumps meant for firefighting. Damage control teams rigged them in the engine room, got them running. They helped. Not much, but every gallon per minute counted. The water level in the engine room stayed constant. Not rising, not falling, just constant. 3 ft deep, cold. The men working down there rotated every 30 minutes.

any longer and hypothermia became a problem. They worked in near darkness, emergency lanterns, hand lights, the only illumination. Up on deck, lookouts watched for periscopes, for torpedo wakes, for anything. The ocean was empty. Gray waves, gray sky, no other ships visible, just Campbell dolphin circling, and 800 m of open water between them and safety.

February 23rd passed. No attacks, no storms, no disasters. Just steady pumping, constant vigilance, slow drifting. Campbell moved with the current northeast away from Newf Finland, away from safety. Every hour of drift meant more hours of towing later. At 2200 hours, HMS Salisbury arrived, an old American fourpipe destroyer transferred to Britain in 1940.

Now manned by Norwegians, Free Norwegian Navy. She’d been hunting Ubot near the convoy. Got orders to reinforce Campbell’s escort. Two escorts now. Better odds. Still not safe. Yubot operated in wolfpacks. If they found Campbell, two escorts might not be enough. Might not matter. Campbell couldn’t run, couldn’t hide, could only float and wait. February 24th.

Still no tow. Campbell drifted northeast away from safety. The crew worked pumps, watched horizons, waited. Commander Hersshfield’s wounds had stopped bleeding, crusted over. His medical officer begged him to let them clean and dress the cuts properly. Hersshfield refused. Said he’d deal with it when they reached port, if they reached port.

Sinbad moved through the ship, visiting crew members, letting men pet him, scratch his ears. The dog seemed to understand something was wrong. Stayed calm, stayed close to the crew. Men took turns sharing their rations with him, saved bits of food. Nobody said it out loud, but everyone thought it.

As long as Sinbad stayed aboard, the ship wouldn’t sink. Superstition maybe, but after 3 days without power, 3 days pumping water, 3 days drifting in yubot waters, men needed something to believe in. At 1500 hours on February 25th, a message came through on emergency radio. The British seagoing tug Tenacity was on route from St.

John’s ETA 26th February, 2 days away. She’d bring two British escorts, take Campbell in tow, get her home. Two more days. Campbell’s crew could manage two more days. They’d already done three. What was two more? The pumps kept running. The water level held steady. The collision mat held. And somewhere ahead, coming through 800 miles of ocean, a tugboat was racing toward them.

Campbell just had to stay afloat until she arrived. At 0900 on February 26th, lookout spotted smoke on the horizon southeast coming toward them. The British tug Tenacity. She left St. John’s 2 days earlier, steamed 800 miles without escort through yubot waters, coming to save Campbell. Tenacity was a seagoing tug built for ocean work.

Powerful engines, heavy towing gear. She’d pulled disabled ships across the Atlantic before, but never one this damaged. Never one flooding this badly. Never one this far from port. She came alongside at 1100 hours. Her crew rigged towing lines, heavy steel cables running from Tenacity Stern to Campbell’s bow.

The connection took 3 hours working in heavy seas. Campbell rolling, lines getting tangled, having to be reset. Finally, at 1,400 hours, the cables were secure. Tenacity took the strain. Her engines roared. The cables went taut, stretched. Water squeezed out of the braided steel. Campbell began to move slowly. Four knots, maybe less, bow pointed southwest toward Newfoundland, toward safety, toward home. 800 m to go.

At four knots, that meant 200 hours, 8 days. Maybe more if weather turned bad, maybe less if weather held. Campbell’s pumps had been running for 4 days. They need to run for eight more. The towing cable stretched behind Campbell. a lifeline, the only thing between her and the bottom. If that cable parted, Campbell would drift again.

If the hole got worse, pumps couldn’t keep up. If another storm hit,she’d capsize. If Ubot found them, both ships would die. Tenacity’s captain knew the risks, came anyway. The two British escorts arrived, took positions ahead and behind, screening the toe, watching for submarines. The convoy was gone, already arrived in North America, safe.

Campbell was alone now. Just her, the tug, two escorts, and 800 m of ocean. February 26th became February 27th. The toe continued, four knots steady. Campbell’s stern rolled lower than her bow, the weight of water in the engine room pulling her down, but she stayed afloat. The collision mat held. Pumps kept pace with the leaking barely.

Commander Hersshfield stayed on the bridge day and night. His wounds had scabbed over, face crusted with dried blood. He hadn’t slept more than an hour at a time since the ramming. Hadn’t left the bridge except to check damage control. His executive officer brought food. Hersshfield ate standing up, watching the towing cable, watching the horizon.

Below decks, Campbell’s crew maintained the pumps. The gasoline pumps ran continuously. When they ran low on fuel, men hauled jerry cans from storage, refueled without stopping the engines. Hand pumps operated in shifts, four men per pump, 30 minutes on, 30 minutes rest, then back to it. The water in the engine room stayed at 3 ft, constant level.

The hole leaked, the mat slowed, the pumps matched it. and equilibrium. Fragile but holding. Sinbad moved through the ship. The dog had his routine. Visit the engine room crew, let them pet him, move to the galley, get scraps, visit the bridge, check on the captain, then find a corner, and sleep. He’d wake up, start the circuit again.

The crew watched him. If Sinbad seemed calm, they stayed calm. If the dog was nervous, something was wrong. Sinbad stayed calm. February 28th, still towing, speed dropped to three knots, heavy seas, tenacity struggled, her engines laboring, Campbell dragging, acting like a sea anchor. The two escorts stayed close, one ahead, one behind.

Their sonar operators searched constantly. No contacts, no yubot. The Wolfpack had moved on, hunting other convoys. Easier targets. March 1st, 6 days since the ramming. Campbell was still afloat, still being towed, still pumping. The crew was exhausted. Men working on adrenaline and coffee. Some had been awake for 36 hours straight. Others grabbed sleep in 10-minute bursts, leaning against bulkheads, sitting on deck wherever they could, but they kept pumping.

March 2nd, 7 days, 600 m behind them, 200 m ahead. St. John’s was getting closer. Not close enough. Not yet. Campbell’s pumps were starting to fail. Gaskets blown, seals leaking, maintenance impossible while running. They just kept going, hoping they’d last, hoping nothing else would break. The towing cable held, the collision mat held, the pumps held, everything held barely.

March 3rd, dawn came at 0600. Cold, clear. Lookout spotted land. Newfoundland. The coast was visible 40 mi ahead. By noon, they could see the harbor entrance, St. John’s, safety, shipyard, dry dock. At 1500 hours, two more tugs came out to meet them. Northwind and Shulamite. Harbor tugs. They’d guide Campbell in, take over from Tenacity, get her to the pier.

At 1700 hours on March 3rd, 1943, USCGC Campbell entered St. John’s Harbor 11 days after ramming U 606, 4 days under tow, 800 m from where she’d nearly sunk. Commander Hersshfield still stood on the bridge, still bleeding through the scabs, still commanding. His ship was home. His crew had saved her. And somewhere below decks, Sinbad was wagging his tail.

Campbell had refused to sink. The shipyard crew saw Campbell and stopped working. They came down to the pier, stared. She was sitting low in the water, stern, almost submerged. A 15oot gash visible below the waterline. Rust streaks running down her hull from the wound. She looked dead. Should have been dead. Somehow wasn’t.

The yard workers got her into dry dock on March 4th, pumped out the engine room, assessed the damage. What they found was worse than expected. The gash was just the start. U 606’s bow plane had punched through the hull plating. Twisted frame members, damaged internal bulkheads. Salt water had flooded the entire engine room for 11 days. Corroded everything it touched.

Generators, turbines, electrical systems, piping, all ruined. The repairs would take 6 months, maybe longer. They’d need to cut away damaged plating, weld in new sections, replace the generators, rebuild the engines, rewire the entire stern section. It was almost easier to build a new ship. Almost. But Campbell had done something no other Coast Guard cutter had done.

She’d sunk a yubot by ramming in the middle of a convoy battle while rescuing survivors, then stayed afloat for 11 days with a hole in her hull. The Coast Guard wasn’t going to scrap her. They were going to fix her, make her better than before, send her back to war. Commander Hersshfield finally let the doctors treat his wounds.

They cleaned the cuts,stitched the deeper ones, bandaged his face. He’d carry scars, small ones, near his ear, on his eyelid. Reminders of February 22nd. He never complained about them. On March 17th, the story hit newspapers across America. Front page headlines. Coast Guard cutter Rams Yubot. First Yubot kill for Coast Guard. Commander Hersshfield decorated. It was the first good news about the Battle of the Atlantic in months.

Americans needed good news. The Yubot were winning, sinking ships faster than shipyards could build them. Campbell’s victory was a bright spot in a dark time. Commander Hersshfield received the Navy Cross. The citation read, “Extraordinary heroism and distinguished service, surprising the hostile undersea craft on the surface during escort operations.

Quick attempt to ram. Destroyed it in a fierce attack. Although painfully wounded by flying shell splinters, he gallantly remained in command throughout the action and during the subsequent period while the Campbell was towed safely into port. He also received the Purple Heart for wounds received in action against the enemy.

Chief Steuart Lewis Ethidge didn’t get his award until 1952, nine years later. The Bronze Star for distinguished service as gun captain of gun 4 during the engagement with U 606. He was the first African-Amean in Coast Guard history to receive the Bronze Star. The delay was typical. Black servicemen often had to wait years for recognition, decades sometimes.

Ethridge waited 9 years. He deserved it on February 22nd, 1943. Got it in 1952. Better late than never. Barely. Campbell stayed in dry dock until July. The yard worked continuously, replaced the damaged hole sections, installed new generators, rebuilt the engines, upgraded her radar, improved her anti-aircraft guns.

When she left dry dock, she was better armed than before, faster, more capable. She returned to convoy duty in August 1943. Back to the North Atlantic, back to hunting yubot. She escorted convoys for the rest of the war. Mediterranean North Atlantic. Never rammed another submarine. Never needed to. By late 1943, the Allies were winning the Battle of the Atlantic.

Yubot were being sunk faster than Germany could build them. The Wolfpacks were broken. Campbell had been part of that. February 22nd was a turning point. Not the turning point, but one of many small victories that added up. One yubot sunk, 12 prisoners taken, 50 Norwegian sailors rescued, one Coast Guard cutter that refused to sink.

Commander Hersshfield stayed with Campbell until December 1943. Then received orders for shore duty, training command, teaching new officers, passing on what he’d learned. He never forgot Campbell. Never forgot February 22nd. Never forgot the 73 men who stayed aboard and kept her afloat. He kept rising through the ranks.

Captain, Commodore, Rear Admiral, Vice Admiral. On June 1st, 1954, he was sworn in as assistant commandant of the United States Coast Guard, second highest position in the service. He served until 1962, 8 years. retired as vice admiral, lived until 1993, 50 years after the ramming. He gave interviews occasionally, talked about Campbell, about the ramming, about the toe, about Sinbad.

He always credited his crew, said they saved the ship, said he just gave orders, they did the work. He was being modest, but he was also right. Campbell kept sailing. 46 years of service, World War II, Korean War, Vietnam War. She became the longest serving cutter in Coast Guard history. They called her the queen of the seas.

Not because she was the biggest, not because she was the fastest, because she refused to die. Just like her commander, just like her crew, just like that February night in 1943 when she rammed the yubot and should have sunk and didn’t. Sinbad stayed with Campbell until 1948, 11 years at sea, longer than most sailors served.

He’d been aboard since 1937, enlisted with a paw print on his enlistment papers, given his own service record, Red Cross identification number, service number. The crew treated him like any other member because he was. He had a battle station, gun deck, stayed there during general quarters. The crew built him a hammock, more comfortable than a bunk, kept him stable during the Atlantic’s long rolls.

He ate with the crew, drank coffee, got into trouble in port. The crew loved him for it. In 1940, Campbell was surveying Greenland. Sinbad went ashore, found sheep, chased them. Some died from exhaustion, others became too nervous to graze. The locals demanded he be shot. The captain refused. Instead, Sinbad faced court marshal.

Found guilty of conduct unbecoming a member of Campbell’s crew. Busted from first class dog to seaman pup. Banned from ever setting paw on Greenland again. The crew thought it was hilarious. Sinbad went awall in Sicily in 1943. Missed the ship’s departure. Military police caught him a week later, shipped him back on a destroyer.

Another court marshal. Another punishment. No more shore leave in foreign ports. He’dbroken the rules. Had to face consequences. Even mascots’s answer to military justice. But on February 22nd, 1943, when Campbell needed luck, Sinbad was there, standing on deck during the battle, staying aboard during the evacuation, keeping the crew spirits up during the tow.

They believed he kept the ship afloat. Maybe he did. Maybe belief was enough. He retired in September 1948, transferred to Barnagate Light Station in New Jersey. Shore duty, he’d earned it. 11 years at sea, multiple campaigns. He wore his medals on his collar, American Defense Service Medal, American Campaign Medal, European African Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal, World War II Victory Medal, Navy Occupation Service Medal, more decorations than most sailors.

He died December 30th, 1951, 14 years old. Buried at Barnagate Light Station, full military honors granite marker at the base of the flag pole. A sailor home from the sea. The current USCGC Campbell carries a statue of Sinbad in her mess, balancing a bone on his nose, his favorite trick. Tradition says it’s bad luck for anyone below the rank of chief to touch the statue.

Old superstitions die hard. U 606 stayed on the ocean floor, 2200 feet down, North Atlantic, approximately 51 degrees north, 42 degrees west. Her crew of 47 became 35 graves. 37 died, most from exposure. Her commander, Oberlutin Wolf Gang Heinrich, was 30 years old. He taken command of U 606 in November 1942, 3 months before Campbell killed him.

She was his first and only command. He’d sunk three merchant ships. Ent Neielson Alonzo Empire Redshank Chattanooga City Expositor damaged two others. Then the Polish destroyer Bersza caught him, damaged his conning tower, forced him to surface. Campbell finished him. Heinrich never had a chance to become one of Germany’s ace commanders.

Never got the kills, never got the glory, never got the Knight’s Cross. He got three months of command, four kills, and a shell fragment that blew him off his conning tower into the North Atlantic. War doesn’t care about potential. The 12 survivors spent the rest of the war in prisoner camps. Canada first, then the United States.

They went home in 1946, 3 years after U 606 sank. Most never talked about it, about the ramming, about watching their boat die, about watching their friends die. They’d done their duty. lost, survived. That was enough. February 1943 was the crisis point of the Battle of the Atlantic. 120 ships sunk worldwide, 82 in the Atlantic.

The Germans were winning, strangling Britain, cutting supply lines. Churchill later wrote, “The only thing that ever really frightened him during the war was the Yubot peril.” March 1943 was worse. 120 ships sunk. The biggest convoy battles of the war. 43 Yubot attacking convoys SC122 and HX229 simultaneously. 22 ships lost in 5 days.

It looked like Germany might actually win. Then came Black May, May 1943. 43 Yubot destroyed. 25% of Germany’s entire operational yubot strength gone in one month. The Allies figured out how to kill submarines. Long range aircraft, escort carriers, better radar, better tactics, better coordination. The Yubot stopped winning.

By June 1943, Admiral Dunits withdrew the Wolfpacks from the North Atlantic. The Battle of the Atlantic wasn’t over, but the crisis had passed. The Allies were winning. Campbell’s ramming on February 22nd was part of that. A small part. One yubot out of thousands. But every yubot sunk mattered. Every convoy protected mattered. Every sailor rescued mattered.

14 merchant ships lost from convoy 166. But 49 made it through because eight escorts fought 19 Yubot because men like Hersfield made decisions. Because crews like Campbell refused to quit. 50 Norwegian sailors pulled from the water alive because Campbell stopped to rescue them. Even when Yubot were hunting, even when it meant becoming a target, that mattered, too.

Campbell sailed for 46 years, longer than any other Coast Guard cutter. She escorted convoys through the rest of World War II. Mediterranean runs, North Atlantic patrols, protecting supply ships, hunting submarines. She never rammed another yubot. Never needed to. The tactics had changed. The technology had improved. Ramming was desperate.

Last resort. February 22nd was the only time desperation worked. After the war, Campbell continued serving. Ocean station duty, weather patrols, search and rescue. She patrolled during the Korean War, deployed to Vietnam in 1968. Operation Market Time, interdicting enemy supply vessels. She steamed over 32,000 mi in the combat zone, destroyed or damaged 105 Vietkong structures, provided fire support for troops ashore.

At 65 years old, she was still fighting. She was decommissioned in 1982. 46 years of service, the oldest continuously commissioned vessel in the United States Coast Guard. They could have made her a museum ship, put her in a harbor somewhere, let tourists walk her decks. But Campbell had one more mission.

In November 1984, the Navy used her as atarget. Pacific Ocean, 22° north, 160° west. A harpoon missile hit her. She stayed nearly intact, settling slowly. As she went under, her crew transmitted a final message. The Queen is dead. Long live the Queen. A reference to the new USCGC Campbell being built.

WMEC909, famous class cutter. The old Campbell slipped beneath the waves 2200 ft down just like U 606. Full circle 41 years after the ramming. The new Campbell was commissioned in 1988. She carries the name, the tradition Sinbad statue in her mess deck, the coat of arms designed by naval historian Samuel Elliot Morrison.

A seahorse on each side, a crown on top, a battering ram in the center. Commemorating February 22nd, 1943. The story lives on. Commander Hersshfield died in 1993, 90 years old, buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Vice Admiral, Navy Cross, Purple Heart. 50 years after ramming U606, he’d seen Campbell decommissioned, seen her sunk as a target, seen the new Campbell commissioned, seen the Coast Guard grow from a small service into a major force.

He’d outlived his ship, outlived most of his crew, outlived the war. But he never forgot February 22nd, never forgot the 73 men who stayed aboard, never forgot the decision to ram. In interviews near the end of his life, he said he felt the presence of higher powers that night. Said they had Jesus on the bow and Moses on the stern getting them through.

Maybe he believed it. Maybe it was the only way to explain how Campbell survived. How a ship with a 15 ft hole in her hull stayed afloat for 11 days. How 73 men pumping water with buckets and prayers kept her from sinking. Maybe faith was the only explanation. Chief Steward Lewis Ethidge lived until 1987, 69 years old.

He wore his Bronze Star, told his grandchildren about gun four, about the all black crew that fired 32 rounds at a yubot, about hitting the target, about making history. He was proud, had earned the right to be. The story of convoy 166 is taught at the Coast Guard Academy. Required reading. How to lead under pressure. How to make decisions when there’s no time.

How to save a ship when everyone says it’s impossible. Hirshfield’s decision to ram is analyzed, debated. Would it work today? Should it have worked then? Was it brilliant or lucky? The answer is both and neither. It was necessary in that moment with that yubot, with that crew. It worked. That’s enough. If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor. Hit that like button.

Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We’re rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day. stories about Coast Guard sailors who saved convoys with ramming attacks and refused to let their ships sink. Real people, real heroism.

Drop a comment right now and tell us where you’re watching from. Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You’re not just a viewer. You’re part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served.

Just let us know you’re here. Thank you for watching and thank you for making sure Commander Hersshfield and Campbell’s crew don’t disappear into silence. These men deserve to be remembered, and you’re helping make that

News

They Mocked His ‘Suicide’ Plan — Until He Blew Up 17 Bridges in Hitler’s Face

They Mocked His ‘Suicide’ Plan — Until He Blew Up 17 Bridges in Hitler’s Face At 0530 on December 17th,…

How One Mechanic’s “Stupid” Cow Paint Job Made His B-17 Unkillable

How One Mechanic’s “Stupid” Cow Paint Job Made His B-17 Unkillable At 0600 on June 8th, 1944, Technical Sergeant…

Miami Hurricanes Cash In On Massive $20 Million Payout, Thanks To Florida State

Miami Hurricanes Cash In On Massive $20 Million Payout, Thanks To Florida State January 10, 2026, 7:16pm EST 219 • By Lou Flavius The…

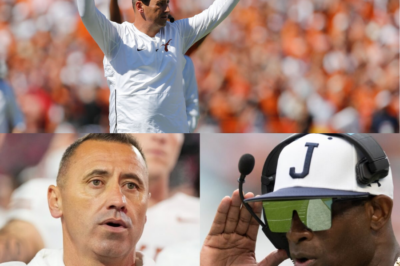

Steve Sarkisian Reacts Quickly After Deion Sanders Raids Texas Roster

Steve Sarkisian Reacts Quickly After Deion Sanders Raids Texas Roster January 10, 2026, 11:57pm EST 89 • By Vipul Dhawas Deion Sanders recruited Liona…

Japan Built An “Invincible” Fortress. The US Just Ignored It

Japan Built An “Invincible” Fortress. The US Just Ignored It At 0730 hours on November 1st, 1943, Lieutenant General Alexander…

It was just a portrait of a Black US Marine and his family — but look more closely at their hands

It was just a portrait of a Black US Marine and his family — but look more closely at their…

End of content

No more pages to load