How a Rejected Marine Burned 7 Japanese Bunkers in 4 Hours

At 10:23 on the morning of February 23rd, 1945, Corporal Hershel Woody Williams lay face down in black volcanic ash 40 yards from a Japanese pillbox that had killed nine Marines in the past 2 hours, listening to his company commander’s words echo in his head. Do you think you could do anything with that flamethrower? Woody was 21 years old, 5′ 6 in tall, 150 lb.

The Marine Corps had rejected him 3 years earlier for being too short. The recruiting sergeant in Charleston, West Virginia, had measured him, looked at the height requirement chart, and told him to go home. Now that same core was asking him to do what tanks couldn’t do, what rifle squads couldn’t do, what three demolition teams had died trying to do.

The pillbox was a concrete tomb with walls 4 ft thick and a firing slit 8 in tall. The Japanese Type 92 heavy machine gun inside had been killing Americans all morning. First squad had tried a frontal assault at 8:30. Four men dead before they’d covered 20 yards. Second squad had tried to flank at 9:15. Three more dead.

A demolition team had tried to get close enough to throw satchel charges at 9:47. Two more dead. Nine Marines, 2 hours, one pillbox. and there were six more pill boxes behind it. The first battalion, 21st Marines, had been stuck in this position since dawn. Seven Japanese bunkers arranged in a staggered line, each one covering the approaches to the others, interlocking fields of fire, reinforced concrete, 4-ft walls that laughed at grenades and shrugged off tank rounds.

Captain Donald Beck had lost most of his officers. Most of his squad leaders were dead or wounded. His company had combat ineffective written all over it. He needed those pill boxes destroyed or his marines would die in this ashfield 660 mi from Tokyo on an island most Americans had never heard of. Beck had one option left. The flamethrower operator that half his marines thought was too small to carry the weapon.

Woody had heard the comments since boot camp. Flamethrower operators were supposed to be big men. The M2 weighed 70 lb, fully loaded, and you had to carry it while running toward machine gun fire. Woody weighed 150 lb soaking wet. The flamethrower was nearly half his body weight. That little guy is going to carry a flamethrower. One Marine had asked during training at Camp Pendleton. He’ll tip over.

Another had said, give it to someone who can actually run with it. Woody carried it anyway. He trained with it for 7 months. He learned to fire in controlled bursts, 2 seconds, 3 seconds maximum. He learned that the effective range was 20 to 40 yards. He learned that the thickened fuel burned at 2,000° and stuck to everything it touched.

He learned that flamethrower operators had a nickname, 4-second men. That was the average life expectancy once you got within range of an enemy position. On Eoima, the nickname was proving accurate. Of the six flamethrower operators Woody had trained and led into battle four days earlier, all five of the others were gone, killed or wounded.

He was the last one. Now, Captain Beck was looking at him across a shell crater with Japanese machine gunfire cracking overhead, asking if the little guy from West Virginia could do what everyone else had failed to do. Woody’s answer, “I’ll try.” Beck told him to pick four riflemen for covering fire. Woody chose Corporal Warren Bourne Holtz, PFC Charles Fischer, and two others.

Their job was simple. Keep Japanese heads down long enough for Woody to cross 40 yards of open ground and get within flamethrower range. If they failed, Woody would be the 10th Marine to die in front of that pillbox. Woody checked his weapon. The M2 flamethrower had two fuel tanks containing 4 and 1/2 gallons of napalm, a mixture of gasoline and thickening agent that the chemical warfare service had perfected for exactly this kind of work.

A third tank held compressed nitrogen at 400 PSI, which forced the fuel through the wand when you pulled the trigger. The ignition system used a revolving cylinder of five phosphorus matches. Five chances to light the fuel. If all five failed, you were standing 20 yards from a machine gun with nothing but an empty metal tube.

The fuel tanks were nearly bulletproof. The nitrogen cylinder was not one round through that tank and it would rupture, not explode, but tear apart with enough force to kill the man carrying it. Woody tightened the shoulder straps. 70 lb settled onto his frame. The harness was designed for bigger men and the straps bit into his shoulders even after 7 months of adjustments. He looked at the pillbox.

40 yards of open volcanic ash. No cover, no concealment, just black rock and the muzzle flashes from the firing slit. Woody started crawling. Bourne Holtz opened fire. Then Fisher, then the other two. Four M1 Garands, barking as fast as the men could work their triggers. Eight rounds. Ping. Reload.

The Japanese machine gun went quiet for 2 seconds as the gunner ducked below the firing slit.Woody covered 10 yards in that silence. His elbows dug into the ash. The fuel tank scraped against volcanic rock. He could hear his own breathing, ragged and fast. The machine gun roared back to life.

Bullets cracked past Woody’s helmet. One round struck the ash 6 in from his left hand. Another hit a rock beside him and sprayed fragments into his cheek. He felt blood running down his jaw, but didn’t stop, didn’t wipe it, kept his hands on the wand, 30 yards from the pillbox. The Japanese gunner was firing in controlled bursts now, traversing left and right, trying to catch Woody in the open.

The man knew his weapon. The Type 92 fired 450 rounds per minute and overheated quickly. Short bursts preserved the barrel and maintained accuracy. Woody counted the rhythm. 3 second burst. 2cond pause. 3-second burst. 2C pause. He timed his movement to the pauses. 25 yd. A bullet ricocheted off his left fuel tank. The sound rang through his skull like someone had struck a bell next to his ear. The tank held.

The napalm didn’t ignite. He kept crawling. 20 yards. Woody was inside the flamethrower’s effective range, but he was also inside the machine gun’s most accurate range. The Japanese gunner could put rounds through a 6-in circle. Woody needed to fire before the next burst found him. He rose to one knee, aimed the flamethrower wand at the firing slit, and squeezed the trigger.

A jet of burning napalm shot across 20 yards of volcanic air. The thickened fuel didn’t scatter or splash. It flowed in a tight, dark stream, almost like water, and poured through the 8-in opening in the concrete. The temperature inside the pillbox exceeded 1,800° in less than two seconds. The napalm stuck to the walls. the weapon, the men.

It burned through cloth, through skin, through everything. Woody heard screaming. He held the trigger for three seconds, then released. The screaming stopped. One down, six to go. Woody dropped flat as bullets cracked over his head. The second pillbox, 60 yards to his left, had a clear angle on his position.

He’d been so focused on the first bunker that he’d forgotten about the interlocking fields of fire. He rolled right, then right again, putting the burning first pillbox between himself and the second gunner. Smoke was pouring from the destroyed bunker. Thick black chemical smoke that smelled like burning diesel and something else, something worse.

Woody didn’t think about the smell. He’d learned not to think about it on Guam. He looked back toward the marine lines. Bourneholtz was reloading. Fischer was firing at the second pill box, trying to keep the gunner suppressed. The other two riflemen were focused on the third and fourth bunkers. Four men providing cover.

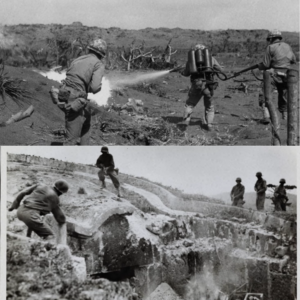

Six pill boxes remaining, and Woody’s flamethrower was down to maybe 5 seconds of fuel. He needed to go back for a fresh tank. Then he needed to do this five more times or six. If you want to see how the marine they called too short to fight destroyed six more pill boxes in the next 3 hours, please hit that like button.

It helps us share more forgotten stories like this, and please subscribe if you haven’t already. Back to Woody. The supply point was 80 yards behind the marine lines. A corporal was waiting there with fresh flamethrowers, tanks that had been filled and pressurized the night before. Woody unslung his nearly empty weapon and dropped it in the ash.

How many? The corporal asked. One. How many left? Six. The corporal helped Woody into a fresh harness. 70 lb settling onto shoulders that were already raw from the first crossing. The straps found the same grooves they’d worn that morning and bit deeper. “The guys are saying you’re crazy,” the corporal said.

Woody didn’t answer. He turned and headed back toward the pill boxes. The second bunker was positioned 60 yards northeast of the first. The Japanese gunner inside had watched Woody destroy the first position. He’d seen the technique, the crawling approach, the controlled burst, the napal pouring through the firing slit. He knew what was coming.

He was ready. Woody couldn’t approach from the south. The third and fourth pillboxes had overlapping fields of fire that covered that route. He couldn’t approach from the east. Open ground, no cover, 80 yards of volcanic ash where the gunner would have plenty of time to cut him down. He went north instead.

A shallow drainage channel ran northwest from the marine position, carved by rainwater into the volcanic rock. It was maybe 18 in deep, enough to hide a man lying flat, but not enough to hide the bulky fuel tanks on his back. Woody crawled into the channel and started moving. At 50 yards from the second pillbox, he heard the shot.

The bullet cracked past his ear and hit the ground ahead of him. Close. Very close. A second shot struck the rim of the drainage channel, spraying volcanic grit into his face. A third shot hit his left fuel tank. The sound was like a hammer, striking an anvil. The impact jolted Woody sideways.

For one frozen moment, he waited for the explosion. the napalm igniting, the fire consuming him. The end. The tank held. The bullet had struck at an angle and ricocheted off the curved steel. Woody pressed himself into the channel floor and tried to locate the shooter. The shots had come from the right, probably the fourth or fifth pillbox, covering the approach to the second.

The Japanese had set up interlocking fire lanes. Attack one bunker and another bunker killed you. He was pinned. couldn’t advance, couldn’t retreat without exposing his back to the shooter. Woody looked toward the marine lines. Bourne Holtz and Fischer were still firing, but they were focused on the second pillbox. They didn’t know about the riflemen on the right.

Woody pulled a white cloth from his pocket, part of a bandage he’d stuffed there that morning. He waved it above the drainage channel and pointed right. Bourneholtz saw it. He shifted his fire. Fiser followed. The shots from the right stopped. Woody scrambled forward. 40 yards, 30 yards. The machine gun in the second pillbox opened up, but the gunner was aiming too high, expecting a running man, not a crawling one.

At 20 yard, Woody noticed something strange. A wisp of blue smoke rising from the top of the pillbox. He’d seen this before. Ventilation pipe. The Japanese soldiers inside were breathing and the bunker needed air flow. Standard construction on Ewima. Every pillbox had one or two pipes built into the roof to prevent the men inside from suffocating.

The pipes were usually 3 to 4 in in diameter, just wide enough for a flamethrower nozzle. Woody changed his approach. Instead of firing through the firing slit, he crawled to the side of the bunker. Out of the machine gunner’s field of view. The concrete wall was rough volcanic aggregate mixed with cement. Good handholds. He climbed.

The roof of the pillbox was flat, covered in ash and debris. Woody found the ventilation pipe near the center. A 4-in steel tube rising about 6 in above the concrete surface. Blue smoke curled from the opening. He could hear voices below. Japanese voices. men talking to each other, unaware that death was standing directly above them.

Woody positioned the flamethrower wand over the pipe opening. The nozzle fit perfectly. He pulled the trigger. Napal poured into the bunker from above. The Japanese soldiers had been facing outward, watching for threats approaching at ground level. They never saw Woody. They never knew he was there until the fire came down from the ceiling.

The screaming was louder this time. More men inside. Woody held the trigger for three seconds, then released. Silence. Two down. Woody slid off the roof and landed in the ash. His legs were trembling. Adrenaline and exhaustion and something else. Something he wouldn’t let himself think about. Five pill boxes left. Woody had been born in Quiet Dell, West Virginia on October 2nd, 1923.

The youngest of 11 children. At birth, he weighed 3 and a2 pounds. The doctor who delivered him had ridden several miles on horseback to reach the family farm, and he hadn’t expected the baby to survive the night. Woody’s mother named him Hershel Woodrow. Hershel after that doctor, Woodro after President Wilson.

Six of his siblings never made it past childhood. The 1918 influenza pandemic swept through Marian County and took them one by one. By the time Woody was old enough to understand death, he had only four brothers and sisters left. His father ran the dairy operation. Every morning before dawn, Woody helped milk the cows.

Every afternoon after school, he loaded the family’s Model A Ford with fresh milk and butter and drove into Fairmont to sell doortodoor. When Woody was 11, his father collapsed in the barn from a heart attack. Lloyd Williams died before anyone could get him to a hospital. The family had no money for doctors, no money for medicine. The Great Depression had hit West Virginia harder than most places, and a dairy farm with no father didn’t have much chance.

Woody dropped out of high school at 17 and joined the Civilian Conservation Corps. He shipped out to Montana to build fencing on government land. He was there on December 7th, 1941, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. His older brothers, Lloyd Jr. and Gerald enlisted in the army the next week. Woody wanted the Marines. He’d seen men from his hometown wearing the dress blue uniforms, and he decided that if he was going to fight, he wanted to look like that.

The recruiting sergeant in Charleston measured him twice. Both times the tape said 5′ 6 in. The minimum height for the Marine Corps was 5’8 in. Sorry, son. You’re too short. Woody drove home. He waited 6 months. By May 1943, the Marines had lost so many men in the Pacific that the height requirement quietly disappeared. Woody went back to the recruiting office in Charleston.

The same sergeant measured him again, looked at the paperwork, and stamped it approved. He said nothing about the rejection 6 months earlier.Now on an island 660 mi from Tokyo, Woody was proving that height had nothing to do with what a man could carry. The third pillbox was built into a natural rise in the volcanic rock. Higher ground than the others, better sightelines.

The Japanese inside had watched Woody destroy two positions. They knew his tactics. They were waiting. Woody approached from the south, using a series of shell craters for cover. The volcanic terrain was broken and jagged. Good for concealment if you moved carefully. Woody moved carefully. At 40 yards, he stopped. Something felt wrong.

The machine gun in the third pill box was silent. No firing, no movement at the firing slit. The Japanese were just waiting. Would he scan the surrounding terrain? If he were defending this position, where would he put a backup? Where would he position men to catch an attacker who thought he’d found an easy approach? There, 30 yards to his right.

A shallow depression in the rock that he dismissed as empty. But now he could see the outline of a helmet, Japanese steel. They’d sent a soldier outside the bunker, a rifleman positioned to catch anyone approaching from the south. The machine gun in the pillbox would drive attackers toward cover and that cover would put them directly in the riflemen’s sights.

The Japanese were learning. Woody had two choices. Go back and find a different route or deal with the rifleman first. He chose the second option. Woody turned and crawled toward the depression where the Japanese soldier was hiding. The man was focused on the approach to the pillbox, watching for Marines who might try to flank the position.

He wasn’t watching his own flank. At 15 yards, Woody rose to one knee and fired. The flamethrower wasn’t designed for individual targets. It was designed for bunkers, for enclosed spaces, for fortified positions, but Napalm didn’t care what it was designed for. Napal burned everything. The Japanese riflemen didn’t scream.

The fire consumed the oxygen before he could draw a breath. Woody turned back toward the pillbox. The machine gunner had heard the flamethrower’s distinctive hiss, the sound of compressed nitrogen forcing fuel through the wand. He knew Woody was close. He opened fire, sweeping the terrain in front of his position, but he was firing blind.

He didn’t know exactly where Woody was. Woody circled east, staying low, using the smoke from the burning riflemen as cover. The smoke was black and thick and smelled like everything wrong with war. He reached the pill box from the side and climbed onto the roof, found the ventilation pipe, inserted the nozzle. 3 second burst, three down.

Woody’s flamethrower was nearly empty. He climbed down, ran back to the marine lines, and grabbed his fourth tank of the day. The corporal at the supply point didn’t ask questions this time. He just helped Woody into the harness and watched him walk back toward the Japanese positions. The fourth and fifth pill boxes were a matched pair positioned 40 yards apart with overlapping fields of fire.

Attack one and the other killed you. The Japanese had designed them as a unit. Each bunker protecting the other, creating a kill zone that no marine had been able to cross. Woody studied the positions from 80 yards out. crouched behind a boulder. The fourth pillbox was slightly lower, built into a depression.

The fifth was elevated with better sight lines, but a narrower firing slit. He considered his options. Crawling toward either bunker would expose him to fire from the other. The drainage channel approach wouldn’t work. Both positions could see the channel from their elevated angles. The smoke from the previous kills had blown away. No cover there.

One option remained. Woody stood up and ran straight at the gap between them. Both machine guns opened fire immediately. Tracers crossed in the air, red streaks marking the paths of bullets that would kill him if any of them connected. Woody ran in a zigzag pattern, changing direction every two or three steps. The human eye tracks motion in predictable ways.

A target that moves unpredictably is harder to hit than a target that runs in a straight line. The Japanese gunners were good, but Woody was faster than they expected, and he was moving in ways they couldn’t anticipate. He dove into a shell crater at the midpoint between the pill boxes. Bullets kicked up Ash around the crater rim.

Both gunners had seen where he went down. They were waiting for him to move. Woody didn’t move. 30 seconds, 45 seconds, a full minute. The firing slowed, then stopped. The gunners were conserving ammunition, waiting for a clear target. Woody exploded out of the crater and sprinted right toward the fourth pillbox.

The gunner in the fifth pillbox tried to track him, but Woody was running perpendicular to his field of fire. The angle was wrong. The barrel couldn’t traverse fast enough. The gunner in the fourth pillbox had a better angle, but Woody was closing the distance too quickly. At 30 yards, themachine gun was deadly accurate. At 15 yards, the gunner couldn’t depress the barrel enough to hit a running man.

Woody reached the pillbox and shoved the flamethrower wand through the firing slit. Point blank range. Two second burst. He didn’t wait to hear the screaming. He was already moving, circling behind the burning bunker, using the smoke and flames as cover from the fifth position. The fifth pillbox had a rear entrance, a tunnel opening that connected to the underground network the Japanese had built beneath Ewoima.

Miles of tunnels, linking bunkers, command posts, ammunition stores, kill the men in one position, and reinforcements could arrive through the tunnels in minutes. Unless you killed them in the tunnels, too.” Woody aimed into the darkness and held the trigger for three full seconds. The napalm rushed down the passage like water down a drain.

He heard screams, not just from the fifth pillbox, but from somewhere deeper underground. The fire was following the oxygen, spreading through the tunnel network, consuming everything in its path. The fifth pillbox went silent. Then a sixth pillbox, 50 yards away, went silent, too. The tunnel had connected them. Woody hadn’t planned to kill two bunkers with one burst, but he’d take it.

Five down, one to go. The seventh pillbox was the largest command bunker for this section of the line. Walls 5 ft thick, reinforced concrete roof designed to survive naval bombardment. The firing slit was narrower than the others, maybe 6 in, and positioned to cover every approach. The Japanese soldiers inside had watched Woody destroy five positions in 3 hours.

They knew everything about him now. They knew his weapon, his tactics, his timing. They knew he approached from unexpected angles. They knew he climbed onto roofs. They knew he used ventilation pipes. They were ready. Woody had one flamethrower tank left. Maybe 7 seconds of fuel. One chance to take down the final bunker. He approached from the west at 1347.

Crawling through a shallow ravine. The covering fire from Bourneholtz and Fiser had thinned. Both men were running low on ammunition. After 4 hours of continuous shooting, the Japanese gunner sensed it. He began firing longer bursts, sweeping the terrain more aggressively. A bullet hit the ground 2 in from Woody’s left hand.

He kept crawling. Another bullet ricocheted off a rock and grazed his helmet. The impact rang through his skull. His vision blurred, then cleared. He kept crawling. 25 yd, 20 yards. Woody rose to one knee. The firing slit was directly ahead, a dark rectangle in gray concrete. He could see the machine gun barrel protruding from the opening.

He could see the muzzle flash as the gunner fired. The gunner saw him, too. For a frozen moment, they looked at each other. the Japanese soldier behind the machine gun and the American Marine with the flamethrower. Two men who understood exactly what was about to happen. The machine gun barrel swung toward Woody’s chest. Woody pulled the trigger first.

The last of his napalm, maybe 3 seconds of fuel, shot through the firing slit. Not enough to fill the bunker, but enough to reach the ammunition stored against the back wall. The secondary explosion blew the concrete roof off the pillbox. The blast wave knocked Woody backward. Debris rained down. Chunks of concrete, twisted metal, things he didn’t want to identify.

He covered his head and pressed himself into the ash. When he looked up, the seventh pill box was a smoking crater. Seven pill boxes, 4 hours, one marine who was too short to serve. Woody stood up slowly. His legs were shaking. His shoulders were raw where the flamethrower straps had rubbed through his uniform and into his skin.

Blood from the rock fragment was still wet on his cheek. He walked back toward the marine lines. Captain Beck was standing at the perimeter, binoculars around his neck. He’d watched everything, counted every crossing, every burst of flame, every near miss. How many? Beck asked. Seven. Beck nodded once. There was nothing else to say.

behind them, 1,000 yards to the south. The American flag that had been raised on Mount Sarabachi that morning was snapping in the Pacific wind. Marines across the island had cheered when they saw it go up. A moment of triumph in the middle of hell. Woody hadn’t seen it. He’d been faced down in volcanic ash, counting machine gun bursts and waiting to die.

The battle for Eojima would continue for five more weeks. 6821 Americans would be killed. 19,217 would be wounded. It would become the bloodiest campaign in Marine Corps history. Of the roughly 900 flamethrower operators deployed to the island, casualty rates in some units exceeded 92%, the weapon that Woody carried made him the priority target for every Japanese soldier on the battlefield.

Fewer than 80 flamethrower operators walked off Ewima alive. Woody was one of them. He fought through the rest of the campaign. On March 6th, a Japanese mortar round exploded near his position.Shrapnel tore into his leg. He was evacuated to a hospital ship and awarded the Purple Heart. 6 months later on Guam, a runner found Woody and told him to report to the general’s tent.

Woody had no idea why. Generals didn’t summon corporals unless something had gone wrong. He walked across the camp expecting a court marshal. The general told him he was going to Washington. The president wanted to give him the Medal of Honor. “What did I do?” Woody asked. On October 5th, 1945, President Harry S.

Truman placed the Medal of Honor around Woody’s neck at a White House ceremony. 13 other servicemen received the Medal that day. Truman told them he’d rather have this honor than be president. I’ll trade you,” one recipient answered. Woody couldn’t speak. He was a farm boy from West Virginia with one year of high school.

He didn’t know how to stand in front of cameras. He didn’t know how to shake hands with presidents. But he learned something after the ceremony that changed everything. The four riflemen who had provided covering fire on February 23rd, Bourneholtz, Fiser, and the two others had not all survived Evoima. Corporal Warren Bourne Holtz was dead. PFC Charles Fischer was dead.

Two of the four men who had kept Woody alive through seven pillbox assaults had been killed. Not on February 23rd. Later, during the five weeks of fighting that followed, they never knew Woody would receive the Medal of Honor. They never knew their covering fire had made it possible. Once I learned that, Woody said years later, my whole concept of the medal changed.

I said, “This medal does not belong to me. It belongs to them. So, I wear it in their honor, not mine. They sacrificed their lives to make that possible.” Woody went home to West Virginia 12 days after the White House ceremony. He married Ruby Meredith, his high school sweetheart, and settled in Huntington. They had two daughters, but the war followed him home.

The nightmare started the first week. Every night, Woody was back on Eojima, crawling through ash, watching men burn. He woke up fighting walls of fire that existed only in his memory. He woke up screaming names that Ruby didn’t recognize. There was no treatment for what Woody had. The term post-traumatic stress disorder wouldn’t exist for another 35 years.

In 1945, veterans were expected to come home, get jobs, raise families, and never speak about what they’d seen. Woody tried. He got a job with the Veterans Administration, helping other servicemen file claims. He raised his daughters. He went to the VFW hall every night and drank beer until the memories faded. It wasn’t enough. His older brother, Gerald, had fought in the Battle of the Bulge.

Gerald came home wounded and broken. He cracked up, Woody said later. Went all to pieces. He just gave up life. He wanted to die, and he did. Not too many years later. Woody was on the same path for 17 years. He fought the war every night in his dreams and drank every evening to forget. His wife Ruby was a Christian.

She took their daughters to the Methodist church every Sunday and asked Woody to come. He refused. He’d seen too much death to believe in God. He’d caused too much death to deserve forgiveness. On Easter Sunday 1962, Woody finally agreed to attend church. He sat in the pew, arms crossed, waiting for it to end.

But the preacher’s words caught him. The sermon was about sacrifice, about giving your life for others, about the Lord dying so that others might live. Woody found himself thinking about Bourne Holtz and Fiser, two men who had laid down fire for 4 hours so that he could destroy seven pill boxes. Two men who had died on an island in the Pacific, far from home, so that he could stand in a church in West Virginia.

17 years later, that all started running through my mind, Woody said later. And then he mentioned that the Lord had also sacrificed his life for me. Woody stood up. He walked to the front of the church. He asked the pastor to pray with him. At 38 years old, Woody Williams gave his life to God. That day, my life changed.

He said, “I walked out of that church a different person than I walked in. The nightmare stopped. He quit drinking. He quit smoking. For the first time since Ima, he found peace. Woody spent the next 33 years working for the Veterans Administration, helping soldiers who had seen what he had seen. He became a lay speaker at his church.

He served as national chaplain of the Congressional Medal of Honor Society for over 30 years. In 2010, at 86 years old, Woody founded the Woody Williams Foundation to honor Gold Star families, the families of service members who died in combat. He thought of them every time he looked at his medal.

He thought of Bourne Holtz’s mother, Fischer’s family. He designed a memorial monument, and spent the next 12 years traveling the country, dedicating memorials in all 50 states. He was on the road over 200 days a year. Even in his 90s, when people asked why he pushed himself so hard athis age, his answer never changed.

This is my way of making sure that our gold star family members are not forgotten. On January 14th, 2016, the Secretary of the Navy announced that a new warship would be named the USS Hershel Woody Williams. The vessel was an expeditionary sea base 784 ft long, designed to carry Marines anywhere in the world.

Woody wrote the ship’s motto, “Peace we seek, peace we keep.” On March 7th, 2020, Woody attended the commissioning ceremony in Norfol, Virginia. He was 96 years old, “Rived in a wheelchair, and smiled when the champagne bottle shattered against the hull.” “Receiving the Medal of Honor is the top man-made miracle of my life,” he told the crowd.

But this ship that bears my name and will sail the seven seas to protect America for many years to come is close to the top. He looked at the sailors who would serve aboard his ship and gave them one instruction. May all those who serve aboard this ship that will bear my name be safe and be proud. On June 29th, 2022, Hershel Woody Williams died at the VA medical center named in his honor in Huntington, West Virginia. He was 98 years old.

He was surrounded by his family. He was the last living Medal of Honor recipient from World War II. The recruiting sergeant in Charleston, who rejected him in 1942 for being 2 in too short, was never identified. The Marine Corps has no record of his name. He never knew that the farm boy he turned away would destroy seven Japanese pill boxes in 4 hours.

He never knew that the kid who stood 5’6 in would become one of the most decorated Marines in American history. He never knew that the United States Navy would name a 784 ft warship after the man he called too short to serve. Some things can’t be measured in inches. If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor. Hit that like button.

Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We’re rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day. Stories about Marines who prove that courage has no height requirement. Real people, real heroism. Drop a comment right now and tell us where you’re watching from.

Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You’re not just a viewer. You’re part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served. Just let us know you’re here. Thank you for watching and thank you for making sure Woody Williams doesn’t disappear into silence.

These men deserve to be remembered, and you’re helping make that

News

German Colonel Captured 50,000 Gallons of US Fuel and Realized Germany Was Doomed

German Colonel Captured 50,000 Gallons of US Fuel and Realized Germany Was Doomed December 17th, 1944. 0530 hours. Hansfeld, Belgium….

German Pilots Laughed At The P-47 Thunderbolt, Until Its Eight .50s Rained Lead on Them

German Pilots Laughed At The P-47 Thunderbolt, Until Its Eight .50s Rained Lead on Them April 8th, 1943. 27,000 ft…

German Generals Laughed At U.S. Logistics, Until The Red Ball Express Fueled Patton’s Blitz

German Generals Laughed At U.S. Logistics, Until The Red Ball Express Fueled Patton’s Blitz August 19th, 1944. Vermacht headquarters, East…

German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States

German POWs Were Shocked By America’s Industrial Might After Arriving In The United States June 4th, 1943. Railroad Street, Mexia,…

How One Mechanic’s “Crazy” Field Modification Made P 47 Thunderbolts Carry 2,500 Pounds Of Bombs

How One Mechanic’s “Crazy” Field Modification Made P 47 Thunderbolts Carry 2,500 Pounds Of Bombs March 1944, a muddy airfield…

How Six “Suicidal” Torpedo Riders Crippled Britain’s Mediterranean Fleet in One Night

How Six “Suicidal” Torpedo Riders Crippled Britain’s Mediterranean Fleet in One Night At 2043, on the night of December 18th,…

End of content

No more pages to load