How One 14 Year Old Girl’s ‘Innocent’ Bicycle Killed Dozens of Nazi Officers

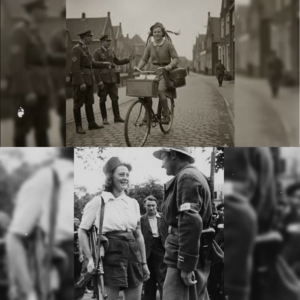

A park bench in Harlem, Netherlands, 1943. A teenage girl with braided pigtails approaches a woman sitting alone. She looks about 12 years old, innocent, harmless. She asks, “What’s your name?” The woman tells her the girl pulls out a pistol, looks her in the eyes, and shoots her dead. Then she gets on her bicycle and rides away.

Her name is Freddy Oversteiggan. She’s 16 years old and the woman she just killed was a Dutch collaborator who had a list of every Jew in the region, names and addresses she was about to hand to the Nazis. That list would have meant death for hundreds of innocent people. Freddy had just saved them all. By the end of the war, she and her sister would assassinate dozens of Nazis and collaborators.

The exact number, no one knows. When asked, Freddy always gave the same answer. One should not ask a soldier any of that. This is the story of two teenage girls who seduced Nazi officers, lured them into the forest, and shot them dead. Girls who learned to kill in an underground potato shed. Girls who refused to murder children, even the children of their enemies.

Girls who remained human while fighting monsters. Freddy Oversteigan was born in 1925 in the village of Shotton just outside Harlem. Her childhood was anything but normal. Her family lived on a housebo. Her father never made much money. Her mother Trenchy was a communist who believed that when you see injustice, you don’t look away, you act.

When Freddy was young, her parents divorced. Her father sang a French farewell song from the bow of the ship as they left. She rarely saw him after that. Trini moved the two girls into a tiny apartment in Harlem. They slept on mattresses stuffed with straw. They had almost nothing, but their mother still made room for others.

Jewish refugees fleeing Germany. Political fugitives running from the Nazis. Strangers who needed a place to hide. Freddy and Truce grew up sharing their beds with people whose names they sometimes didn’t even know. They made dolls for children suffering in the Spanish Civil War. They learned early that some things matter more than comfort.

Their mother taught them one lesson. If you have to help somebody, you have to make sacrifices for yourself. It was a lesson they would never forget. May 10, 1940. Nazi Germany invaded the Netherlands. The Dutch army held out for 5 days, then surrendered. Freddy was 14. truce was 16. The occupation began immediately. German soldiers filled the streets.

Nazi flags hung from buildings. New rules, new restrictions, new fears. Freddy remembered what it felt like. I remember how people were taken from their homes. The Germans were banging on doors with the butts of their rifles that made so much noise you’d hear it in the entire neighborhood. And they would always yell. It was very frightening.

But the Overstegan family didn’t hide. They fought back. Freddy and Trus joined their mother, distributing anti-Nazi pamphlets and illegal newspapers. At night, they’d sneak through the streets with paste and paper, covering German propaganda posters with their own messages. The Netherlands must be free. And don’t go to Germany.

For every Dutch man working in Germany, a German soldier goes to the front. Then they’d race away on their bicycles, hearts pounding, knowing that if they were caught, they’d be shot. But they were never caught. Two young girls on bicycles who would suspect them. Their activities didn’t go unnoticed.

In 1941, a man named France Vanderval came to their door. He was the commander of the Harlem Council of Resistance, part of the underground network fighting the Nazi occupation. He’d heard about the Overstegan family, the mother who hid refugees, the daughters who distributed illegal pamphlets. He wanted to recruit them. He asked Trenchy, “Can your daughters join the resistance?” Freddy was 14.

Truce was 16. Their mother said yes. The girls said yes. But Vanderwhe wasn’t convinced yet. He needed to know if they could be trusted, if they would break under pressure. So, he tested them. A few days later, he returned to their apartment. This time dressed as a Gustapo officer. He burst through the door, waving a gun, screaming in German, demanding to know where a Jewish man was hiding.

Freddy and Truce didn’t break. They didn’t give up a single name. Instead, they fought back, kicking and hitting the man they thought was a Nazi, refusing to betray anyone, even if it meant their own deaths. Vanderve stopped the act and revealed who he really was. They had passed the test. Now he told them what joining the resistance would actually mean.

You’ll learn to sabotage bridges and railway lines. He paused. And you’ll learn to shoot Nazis. Truis looked at her little sister. Freddy grinned and said, “Well, that’s something I’ve never done before.” Their mother gave them one piece of advice before they left. Always stay human. The Oversteiggan sisters were taken to an underground potato shed. There, in the darkness beneath theearth, they learned to fire a weapon.

They learned how to aim, how to stay calm, how to kill. Their first mission wasn’t assassination. It was arson. Nazi warehouses needed to burn, but they were guarded by SS soldiers. The plan was simple. Freddy and Truis would approach the guards, talk to them, flirt with them, distract them with smiles and laughter while the rest of the resistance slipped in from behind, and set the fires. It worked perfectly.

The warehouses burned. The guards never suspected the two teenage girls who had been chatting with them moments before. Vanderve saw what they were capable of. These girls could go places men couldn’t. They could get close to targets no one else could reach. Their youth and innocence were weapons more powerful than any gun.

It was time for them to learn what that really meant. Freddy’s victim wasn’t a German soldier. It was a Dutch woman. The resistance had received intelligence about a collaborator, a Dutch citizen working with the Nazis. This woman had compiled a list, names, addresses, every Jew in the region. She was planning to hand it to the Germans.

That list was a death sentence for hundreds of people, men, women, children, entire families who would be rounded up, deported, murdered. The resistance gave Freddy the assignment. She rode her bicycle to a public park where the woman would be. She found her target sitting on a bench. Freddy approached, “Casual, innocent. Just a girl with braided hair.

She asked, “What’s your name?” The woman told her. Freddy confirmed she had the right target. She pulled out her pistol, looked the woman in the eyes, and shot her. The woman fell. Freddy got on her bicycle, and rode away. Later, she would describe what it felt like. The first thing you want to do when you shoot somebody is to pick them up.

The instinct to help even after you’ve killed them. That impulse never left her. No matter how many times she pulled the trigger. Freddy and Truce developed their own techniques. Sometimes they worked alone, sometimes together. Their methods evolved as they learned what worked. The forest. They would go to bars and taverns where German officers gathered.

One sister would walk in alone, strike up a conversation with an officer, laugh at his jokes, touch his arm, lean in close. Then she’d ask the question, “Would you like to go for a stroll in the woods?” The officer always said yes. They’d walk into the forest together, deeper and deeper, away from the roads, away from witnesses.

And there, hidden among the trees, the other sister would be waiting. One bullet to the head, the officer would fall. They’d leave his body in a hole that had already been dug and walk away the bicycle. Other times, speed was the weapon. Truis would pedal the bicycle while Freddy sat on the back pistol ready.

They’d identify their target walking down the street, ride past him, and Freddy would fire. Then they’d keep riding. Just two girls on a bicycle. Nothing unusual. We always went by bike, never walked. That was too dangerous, Truce explained later. I always made sure the coast was clear. That worked very well. The doorstep. Sometimes they’d follow a target home, learn his address, his routine.

Then they’d knock on his door. When he opened it, he’d see a young girl, innocent, harmless. By the time he realized the danger, it was too late. In 1943, a third member joined their cell. Her name was Jean Ha Yana Shaft. Everyone called her Hani. She was different from the Oversteiggan sisters. HY came from a middle-class family. Her father was a teacher.

She was studying law at the University of Amsterdam, planning to become a human rights lawyer. But when the Nazis demanded that all students sign a loyalty pledge to Germany, HY refused. She was expelled. She didn’t go home. She joined the resistance. Hy had distinctive features that made her stand out.

bright red hair, green eyes, pale skin, the kind of face people remembered. It would eventually get her killed. But first, she would become one of the most feared resistance fighters in the Netherlands. Vanderve tested her the same way he’d tested the Overstegan sisters. He gave her a gun and sent her to assassinate a Nazi officer.

She approached the target, raised the weapon. Her hands were shaking. She pulled the trigger. Click. The gun was empty. It had been a test. The Nazi officer revealed himself as Vanderveil. She had passed. Now she joined Freddy and Trudis. The three young women formed a lethal unit. Hanny was the intellectual, the planner, the one who thought through every detail.

Truis was the leader, decisive, fearless, the one who made the hard calls. Freddy was the scout who mapped everything out in advance and knew every escape route. Together, they were unstoppable. The three women didn’t just kill. They blew up railway lines to stop deportation trains carrying Jews to concentration camps.

They smuggled Jewish children out of the country, sometimes walking themacross borders in the middle of the night. They stole identity papers and forged documents to help refugees disappear. They gathered intelligence on German troop movements and passed it to Allied forces. And yes, they killed German soldiers, Nazi officers, and Dutch collaborators.

The collaborators were often the most dangerous targets. Dutch citizens who betrayed their own people for money or power, who turned in their Jewish neighbors, who worked for the Gustapo. Freddy and Truce focused more and more on these traders as the war went on. We were dealing with cancerous tumors in society, Truce explained.

You had to cut them out like a surgeon. You couldn’t arrest them. You couldn’t try them. There was no other solution. One day, an order came from resistance leadership. The target, Arthur Seinquart, the right commissioner of the Netherlands, one of the most powerful Nazis in the country. The mission, kidnap his children. The plan, use the children as leverage to force him to release resistance prisoners and if he refused, kill the children.

Freddy, Truce, and Hanny refused the mission. Freddy said, “We are not Hitlerites. Resistance fighters don’t murder children. They had killed many people. They would kill more, but children never.” That was the line between resistance and terrorism, between fighting evil and becoming it. They would not cross it.

Truis was cycling through the streets one afternoon when she saw something that would haunt her for the rest of her life. A Dutch SS soldier, a Dutchman who had joined the Nazi forces, was standing in the street. He had grabbed an infant from a family. The father was there, the baby’s sister. They were screaming, hysterical.

The soldier held the baby up and smashed it against the wall. The child died instantly. Troubis stopped her bicycle. She pulled out her pistol and shot the soldier dead. Right there in the middle of the street. It wasn’t an assignment. There were no orders. That wasn’t a mission, she said later. But I don’t regret it.

Some things don’t need orders. By 1944, Hanny Shaft was one of the most wanted people in the Netherlands. Her red hair had been spotted at too many scenes. Witnesses described her. Word spread. The Nazis issued a bulletin. Find the girl with the red hair. Hy dyed her hair black, started wearing glasses, changed her appearance as much as she could, but she didn’t stop fighting.

In June 1944, she and a fellow resistance fighter named Yan Boneamp were assigned to kill a Dutch collaborator named William Ragoot. They found him. Bone camp shot him, but Ragoot didn’t die immediately and in the chaos, Bone Camp was shot in the stomach. HY escaped. Bone Camp was captured. He was taken to a hospital, dying. The Nazis interrogated him.

He refused to talk. Then they tried a different approach. An officer pretended to be a resistance member, told Bone Camp he was a friend, that he wanted to help. Bone Camp, delirious from blood loss and medication, believed him. He gave up Hie’s address. He died shortly after. The Nazis raided Hie’s parents’ home.

They arrested her mother and father and sent them to a concentration camp. Hie went into hiding. She couldn’t fight anymore. If she was captured, everyone she knew would die. For months, she stayed underground. But she couldn’t stay hidden forever. March 21st, 1945. The war was almost over. Allied forces were advancing.

Liberation was weeks away. HY was cycling through Harlem, carrying copies of an illegal communist newspaper and a pistol. She was stopped at a Nazi checkpoint. They searched her. They found everything. She was arrested. They took her to a prison in Amsterdam. For weeks, they interrogated her, tortured her, kept her in solitary confinement.

They knew they had captured someone important, but they needed her to confirm it. Eventually, they noticed something. Her hair was black, but her roots were growing in red. They had found the girl with the red hair. Hie admitted to her assassinations. She confessed to what she had done, but she never gave up a single name. Not one member of the resistance.

Not Freddy, not TRS, no one. She protected her friends until the very end. April 17th, 1945. 18 days before the Netherlands would be liberated. The war was over. Everyone knew it. There was even an agreement between the Nazis and the Dutch resistance to stop executions. But Willie Les, the Nazi officer in charge, ignored it. He wanted Hanny Shaft dead.

Two Dutch collaborators, traitors to their own country, were assigned as executioners. Their names were Mata Schmidtz and Martin Kyper. They took Hannie to the sand dunes of Ovine, the same dunes where hundreds of resistance fighters had already been killed and buried. Schmidz raised his pistol and fired. The bullet grazed H’s head.

It wounded her, but it didn’t kill her. She looked at her executioner and said, “I shoot better than you.” Quiper raised his submachine gun and fired. Hanny Shaft died in those dunes. She was 24years old. They buried her in a shallow grave. So shallow that her red hair was still visible above the sand. The Netherlands was liberated on May 5th, 1945, 18 days after HY died.

After the war, they found 422 bodies in the Overine Dunes, 421 men and one woman, Hanny Shaft. She was given a state funeral. Queen Wilhelmina called her the symbol of the resistance. But Freddy and Truce, they received nothing. For decades, the Dutch government ignored them. Why? Because they were communists. During the Cold War, anyone with communist ties was sidelined, forgotten, treated with suspicion.

The sisters who had risked their lives to save their country were treated like enemies. Truce coped by creating art. She became a sculptor, making memorials to the resistance. She wrote a memoir. She spoke publicly about what they had done. Freddy chose a different path. I coped by getting married and having babies. She said she married a man named Yan Decker, had three children, and tried to build a normal life, but the past never let her go.

She suffered from insomnia, nightmares that came without warning. Every year on May 4th, Remembrance Day in the Netherlands, she woke up with dread. When people asked how many people she had killed, she always gave the same answer. One should not ask a soldier any of that. She never said the number. Neither did Truis.

Some things you carry alone. For almost 70 years, Freddy and Truis waited. Finally, in 2014, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Ruty invited them to a ceremony. He awarded them the Mobilization War Cross, a military honor for service during World War II. Freddy was 89 years old. Truce was 91. Freddy’s son said it was the happiest day of his mother’s life.

After 69 years, someone finally said, “Thank you.” Streets in Harlem were named after them. Their story was told in books and documentaries, but for most of their lives, they had lived in silence, unrecognized, unhonored. Two teenage girls who had killed Nazis with their bare hands, forgotten by the country they saved.

Truce Oversteigan died on June 18th, 2016. She was 92 years old. Freddy Oversteiggan died on September 5th, 2018, one day before her 93rd birthday. Throughout her life, Freddy visited Hanny Shaft’s grave. She left red roses for the friend who didn’t make it. When asked what advice she had for future generations, Troop is said, “When you have to make a decision, it must be the right one, and you must always remain human.

” Those were the words their mother had given them before they joined the resistance. Always stay human. Freddy and troops killed people. They shot men in forests and on street corners. They watched the life leave their enemy’s eyes, but they remained human. They cried after every kill. They refused to murder children.

They carried the weight of what they’d done for the rest of their lives. The Nazis killed millions systematically, industrially, without remorse, and lost their humanity entirely. That’s the difference. During World War II, 90% of the Dutch population tried to live their lives as normally as possible under Nazi occupation.

5% collaborated with the enemy. 5% joined the resistance. Of that 5%. Only a handful of women took up arms and even fewer killed with their own hands. Freddy Oversteiggan was one of them. a 14-year-old girl with braided pigtails and a pistol hidden in her bicycle basket. She wasn’t a hero from a movie.

There was no dramatic music, no slow motion shots, no Hollywood ending, just a teenage girl who decided that some things are worth killing for and some things are worth dying for. The three of them, Freddy, Truce, and HY, are believed to have killed dozens of Nazis and Dutch collaborators. Some estimates say the number exceeded 100. Freddy lived to be 92 years old.

She never told anyone how many Nazis she killed and she never apologized for any of

News

The US Army Couldn’t Evacuate the Wounded — So a Mechanic Built “Miss Mercy” the Jeep Ambulance

The US Army Couldn’t Evacuate the Wounded — So a Mechanic Built “Miss Mercy” the Jeep Ambulance The mud in…

“Stunning” New York Yankees Fan Went Viral In The Stands For Obvious Reasons As The Team Advanced To The ALDS [PHOTOS]

The New York Yankees are on to the next round. New York eliminated Boston inside Yankee Stadium on Thursday night, and they…

Former NFL Quarterback Mark Sanchez In Critical Condition After Horrific Stabbing Incident In Indianapolis

Former NFL quarterback Mark Sanchez is in critical condition following a stabbing incident in Indianapolis on early Saturday morning. Sanchez, 38, was…

Harrison Butker Leaks Heartbreaking Final Text Messages He Received From Charlie Kirk Before The 31-Year-Old Activist Was Assassinated [PHOTO]

Conservative activist Charlie Kirk has tragically lost his life at the hands of senseless gun violence. Kirk, a conservative media personality,…

Dolphins’ Tyreek Hill Gruesomely Snaps His Leg, Carted Off In Air Cast vs. Jets on MNF [VIDEO]

Tyreek Hill is done for the 2025 season. On Monday Night Football against the New York Jets, the star wide receiver tried to finish…

Is THIS Kayla Nicole’s Reaction to Taylor Swift’s Possible Life of a Showgirl DIG?

Taylor Swift’s The Life of a Showgirl is already taking the internet by storm and fans are taking guesses at…

End of content

No more pages to load