How One Physicist’s “Magic Fuse” Shot Down 75% of V-1 Rockets — Germans Never Figured Out How

Summer 1944, southern England. German V1 flying bombs. Hitler’s vengeance weapons screamed across the English Channel at 400 mph, targeting London. British anti-aircraft batteries fired thousands of rounds daily, trying to stop the pilotless missiles before they reached the city. The problem was brutal mathematics.

A V1 flew too fast for visual tracking. By the time gunners calculated trajectory, aimed, and fired, the missile had moved. Even when shells passed within 20 ft of a V1, they sailed harmlessly by. Traditional artillery shells only detonated on direct impact, missed by inches, and you might as well have missed by miles.

British gunners needed shells to explode near the target, not hit it directly. They needed some way for artillery rounds to sense when they were close to an enemy aircraft and detonate automatically. They needed magic. What they got was physics. In July 1944, British anti-aircraft batteries defending London received a new type of Americanmade artillery shell.

No special instructions, no technical briefings, just orders. Use these shells instead of the old ones. Gunners loaded the new ammunition and fired at incoming V1s. The results seemed impossible. Shells that passed within 70 ft of V1 rockets exploded automatically. No impact needed. The blast waves shredded the flying bomb’s thin aluminum skin.

V1s tumbled from the sky in pieces. Interception rates jumped from 24% to 79% in less than 2 weeks. German intelligence monitoring the sudden collapse of V1 effectiveness was baffled. Captured German documents showed frantic attempts to understand what had changed. They interrogated captured British gunners.

They examined unexloded British shells. They analyzed engagement reports. Nothing made sense. German engineers found no timing mechanisms in the shells, no barometric triggers, no photoelectric sensors, just a small sealed tube in the fuse that appeared to be some kind of primitive radio component.

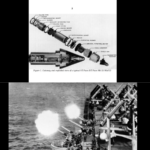

Why would an artillery shell need a radio? The Germans never figured it out. The device that shot down 75% of V1 rockets, destroyed countless German aircraft, revolutionized naval anti-aircraft defense, and changed warfare forever, was called the VT fuse. Officially the variable time fuse, unofficially the proximity fuse.

It was a miniature radar system, small enough to fit inside an artillery shell, rugged enough to survive being fired from a gun at forces exceeding 20,000 times gravity, sophisticated enough to detect targets and trigger detonation at the optimal distance, and simple enough to be mass- prodduced by the millions. The Germans had radar, they had artillery, they had some of the world’s best physicists and engineers, but they never invented the proximity fuse.

This is the story of how American and British scientists created a weapon so advanced that enemies couldn’t understand it even when holding pieces of it in their hands. A weapon so secret that its existence wasn’t fully disclosed until after the war ended. A weapon that killed not through explosive power but through perfect timing.

And it started with one physicist asking a question nobody else had thought to ask. What if we could make shells smart enough to know when to explode? The journey to the proximity fuse began not with military research, but with a peacetime observation about radio waves. In the 1920s and 1930s, radio engineers noticed a curious phenomenon.

When aircraft flew near radio transmitters, the signal strength fluctuated. The metal bodies of aircraft reflected radio waves, creating interference patterns. Engineers considered this a nuisance, something to be filtered out or ignored. Except one person didn’t ignore it. Merl Tuvi, an American physicist at the Carnegie Institution in Washington DC, had spent the 1930s working on radio wave propagation.

He’d helped develop techniques for measuring the ionosphere by bouncing radio signals off it and timing how long they took to return early radar principles, though nobody called it that yet. In 1940, as war consumed Europe and American involvement seemed increasingly likely, Tuva attended a meeting of the National Defense Research Committee.

The topic, improving anti-aircraft fire effectiveness. The statistics were grim. Traditional anti-aircraft shells had impact fuses. They only exploded when hitting something solid. Against aircraft, this meant near misses accomplished nothing. You needed a direct hit or the shell was wasted. Direct hits were rare.

Anti-aircraft gunners in the Spanish Civil War and early World War II combat achieved hit rates around 1 to 2%. It took thousands of rounds to bring down a single aircraft. Tuva listened to military officers describe the problem. They wanted better targeting computers, better optical sights, better training, all focused on making gunners more accurate.

Tuve asked a different question. Why do we need direct hits? What if shells could explode when they got close to aircraft? The obviousanswer was timing fuses, shells preset to explode at specific altitudes. These existed and worked reasonably well for barrage fire, creating a wall of explosions that aircraft flew into, but they required knowing the exact altitude of enemy aircraft, which was difficult to determine accurately in combat.

Tuveet proposed something different. What if artillery shells carried miniature radio transmitters and receivers? The transmitter would send out radio waves. When those waves reflected off nearby aircraft, the receiver would detect the reflection. When the reflected signal reached sufficient strength indicating close proximity to a target, the fuse would trigger detonation.

Essentially, a tiny radar system inside every artillery shell. The idea seemed absurd for multiple reasons. First, the radio components would need to survive being fired from a gun. Artillery shells experienced acceleration forces exceeding 20,000 grimes, 20,000 times Earth’s gravity for several milliseconds when fired.

Vacuum tubes, the foundation of 1940s electronics, were notoriously fragile. They shattered if you dropped them on a table. How could they survive being shot from a cannon? Second, the system would need to be tiny. A standard 5-in anti-aircraft shell had a fuse cavity measuring roughly 3 in tall and 2 in in diameter.

Into that space, you needed to fit a radio transmitter, receiver, antenna, battery, safety mechanisms, and detonation circuitry. Third, it needed to be cheap. Anti-aircraft batteries fired thousands of rounds during engagements. If each fuse cost as much as a luxury car, the system would be economically impossible. Fourth, it needed to be reliable.

A 50% failure rate would be unacceptable. These devices needed to work nearly 100% of the time in all weather conditions at temperatures from arctic cold to tropical heat. Every electronics expert Tuveet consulted said it couldn’t be done. Tuveet assembled a team. Anyway, the proximity fuse development program began officially in 1940 under section T of the National Defense Research Committee. The T stood for Tuve.

The project received high priority and essentially unlimited funding. The challenge was so daunting that success seemed nearly impossible. But the potential payoff was so enormous that failure to try seemed criminally negligent. The team Tuveet assembled included some of America’s best physicists and engineers.

Lawrence Haftd, Richard Roberts, Alexander Ell, and dozens of others. They set up operations at the Applied Physics Laboratory, a new facility established specifically for proximity fuse development at John’s Hopkins University. The first challenge was creating vacuum tubes that could survive being fired from a gun.

Standard vacuum tubes of the era were fragile glass constructions with thin filaments suspended inside. Firing these from a gun would be like shooting a wine glass out of a cannon. Catastrophic failure was guaranteed. The team tried everything. They experimented with smaller tubes, thicker glass, different filament materials, better mounting systems, shock absorbers, dampening mechanisms.

Everything failed. Tests involved loading prototype fuses into artillery shells and firing them at a test range. After each shot, technicians would recover the shell and examine the fuse. Month after month, the vacuum tubes arrived shattered, filaments broken, glass cracked, complete failures. The breakthrough came from thinking about the problem differently.

Traditional vacuum tube filaments were thin wires suspended from supports designed to have minimal mass. The team realized this design philosophy was backwards for their application. Instead of making filaments as delicate as possible, they made them as rugged as possible. They created vacuum tubes with thick, short filaments, tubes with reinforced glass tubes where every component was designed to survive shock rather than maximize electrical efficiency.

The new tubes were crude compared to standard electronics. They had higher power consumption, lower amplification, more electrical noise. They violated every principle of good radio engineering, but they survived being shot from guns. By late 1941, the team had vacuum tubes that could withstand 20,000 grims of acceleration.

The tubes weren’t elegant, but they worked. The second challenge was creating a radio system small enough to fit in a shell fuse. Standard radar systems in 1941 filled entire rooms. They had separate transmitter and receiver units, complex antenna arrays, sophisticated signal processing equipment. The team needed to miniaturaturize all of that into a package smaller than a soda can.

They started with the frequency. Lower radio frequencies required larger antennas, so they chose a relatively high frequency around 200 megahertz. This allowed antenna sizes measured in inches rather than feet. For the antenna, they got creative. The shell’s nose cone itself became part of the antenna system.

Bycarefully shaping the metal components, they created an antenna that worked without requiring separate external elements. The transmitter and receiver shared components. Another space-saving innovation. Instead of separate circuits, they built a system that alternated between transmitting and receiving thousands of times per second. Power came from a miniature battery that activated only when the shell was fired.

Before firing, the fuse was electrically dead, a safety feature that prevented premature detonation. The acceleration of firing activated a mechanical switch that connected the battery, starting the fuse electronics. By mid 1942, the team had working prototypes that fit inside artillery shell fuses.

The prototypes were expensive. Each one cost about $700, equivalent to roughly $12,000 in modern money, but they worked. The third challenge was making the fuses reliable and manufacturable. Early prototypes had failure rates around 30 to 40%. Sometimes the vacuum tubes failed. Sometimes the batteries died prematurely.

Sometimes the radio circuits malfunctioned. Sometimes the detonation mechanism jammed. The team implemented ruthless quality control. Every component was tested individually before assembly. Every assembled fuse underwent multiple inspections. Funzes were subjected to vibration testing, temperature cycling, humidity exposure, and shock testing that simulated gunfiring.

Manufacturers were brought into the development process early. Engineers from companies like Rathon, Sylvania, and Westinghouse worked alongside the Applied Physics Laboratory team designing fuses that could be mass- prodduced. By late 1942, fuse reliability had improved to around 90%.

Manufacturing costs had dropped to about $18 per fuse, still expensive, but economically feasible for military use. The fourth challenge was keeping the entire program secret. The proximity fuse represented such a significant technological advantage that premature disclosure could be catastrophic. If Germany or Japan learned about the fuse existence and principles, they might develop counter measures or create their own versions. Security was extreme.

The fuse was given multiple cover names. VTF fuse officially variable time actually vacuum tube fuse mark 32 and several others. Workers at manufacturing plants often didn’t know what they were building. Components were manufactured at separate facilities and assembled elsewhere. Field use restrictions were initially severe.

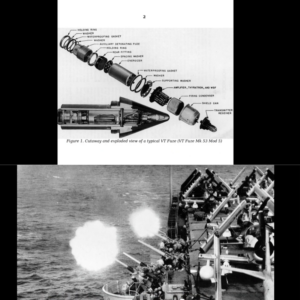

The fuses couldn’t be used over land where enemy forces might recover unexloded shells and examine them. Early deployment was limited to naval anti-aircraft use over water where failed shells would sink and be unreoverable. The first combat use of proximity fuses came in January 1943 during the naval battle of Renel Island in the Pacific.

American cruisers used proximity fused 5-in shells against Japanese aircraft attacking the fleet. The results shocked everyone involved. Japanese aircraft approaching the American fleet ran into a wall of explosions. Shells that passed within 70 ft of aircraft detonated automatically, creating lethal fragmentation clouds. Japanese pilots, accustomed to maneuvering to avoid American anti-aircraft fire, found that evasion didn’t work.

Shells didn’t need direct hits. They just needed to get close. American anti-aircraft effectiveness jumped from roughly 1% one aircraft destroyed per 100 rounds fired to over 10%, a 10-fold improvement. Some engagements achieved 20 to 30% effectiveness. Japanese commanders noticed the change immediately. Intelligence reports noted that American anti-aircraft fire had become mysteriously more effective.

Japanese pilots reported shells that seemed to know when aircraft were nearby, but Japanese intelligence couldn’t determine the mechanism. They recovered shell fragments from aircraft that were damaged, but managed to return to base. They found no obvious mechanical timing devices, no apparent photoelectric sensors, no visible external triggers.

The secret held by mid 1944, proximity fuse production exceeded 1 million units per month. The fuses had proven reliable, effective, and most importantly, secret enough that enemies hadn’t developed counter measures. Then came the V1 flying bombs. Germany’s V1 Vergel Tungvafa Vengeance Weapon was a pilotless cruise missile, essentially a flying bomb powered by a pulsejet engine launched from sites in occupied France and the Netherlands, V1s flew at about 400 mph toward London, carrying an 11,70 lb high explosive warhead. The V1

offensive began on June 13th, 1944, one week after D-Day. Over the next several months, Germany launched over 10,000 V1s at London and other targets in southern England. British defenses initially struggled. V1s flew too fast for most fighter aircraft to intercept. Anti-aircraft guns could engage them, but traditional impactfused shells were ineffective.

The V1’s small size and high speed made direct hits nearly impossible. In July 1944,British anti-aircraft batteries received Americanmade proximity fuses. The shells were designated for the standard British 3.7 in anti-aircraft gun. Instructions were simple. Replace your current ammunition with these shells. No technical explanation provided.

Gunners were told the shells would explode near targets automatically. The first day using proximity fuses, British anti-aircraft batteries shot down 17 vault ones out of 91 launched, a 19% success rate. Within 2 weeks, as gunners learned to use the new ammunition effectively, success rates exceeded 75%. Three out of every four V1s launched were being destroyed before reaching London.

The impact on London was immediate and dramatic. V1 attacks that had been killing hundreds of civilians weekly dropped to sporadic nuisance raids. The psychological terror of the buzzbomb offensive evaporated. Citizens who’d been fleeing London returned. German intelligence was completely baffled. Captured German documents from late 1944 show frantic attempts to understand what had changed.

One report noted, “British anti-aircraft effectiveness has increased inexplicably. Previously, successful interception required multiple direct hits. Now, shells appear to detonate in proximity to V1 weapons without impact, mechanism unknown. German engineers examined V1s that had been damaged by anti-aircraft fire, but managed to crash land more or less intact.

They found fragment damage patterns consistent with shells exploding nearby, not direct hits. They recovered unexloded British anti-aircraft shells. Examination revealed the small sealed tube in the fuse, the vacuum tube radio assembly. German technicians identified it as some kind of electrical component, but couldn’t determine its function.

Some German engineers theorized the shells used photoelectric sensors triggered by the V1’s exhaust flame. Others thought acoustic sensors detected the distinctive pulsejet engine noise. A few suggested radio-based proximity detection, but dismissed the idea as technologically impossible. There was no way to fit a radar system into an artillery shell fuse.

The correct explanation was literally in their hands, and they couldn’t see it. By September 1944, the V1 offensive had effectively ended. The launch sites in France had been overrun by Allied advances. The few V1s still being launched were intercepted at such high rates that the weapons had become militarily useless.

The proximity fuse had destroyed Hitler’s vengeance weapon offensive. If you’re fascinated by the secret weapons and technologies that changed World War II, make sure to subscribe to the channel. We bring you the untold stories of innovations that seemed impossible but became reality. Hit that notification bell so you don’t miss our upcoming videos on the hidden technologies that won the war.

The proximity fus’ success against V1s was spectacular, but it represented only one application of a technology that revolutionized multiple aspects of warfare. In naval operations, proximity fuses transformed anti-aircraft defense. Before proximity fuses, American and British warships fired thousands of rounds to shoot down single aircraft.

Japanese kamicazi attacks in 1944 45 overwhelmed defensive fire through sheer numbers. Ships simply couldn’t shoot down enough aircraft fast enough. Proximity fuses changed the equation. Each shell that passed near an aircraft had a high probability of destroying or damaging it. Ships that previously needed sustained fire to down one aircraft could now destroy three or four with the same ammunition expenditure.

The Battle of Lake Gulf in October 1944 demonstrated the impact. American ships using proximity fuses achieved anti-aircraft kill rates three to four times higher than ships using traditional ammunition. Japanese aircraft attacking ships with proximityfused anti-aircraft shells faced casualty rates that made missions nearly suicidal.

In the Battle of Okinawa, proximity fuses proved critical to fleet defense against kamicazi attacks. American ships fired over 1.2 million proximity fused shells during the Okinawa campaign. The fuse’s effectiveness meant that even though Japanese aircraft achieved some hits through sheer numbers, the damage was far less than it would have been without proximity fuses.

Captured Japanese documents after the war showed that Japanese naval commanders recognized American anti-aircraft fire had become mysteriously more lethal starting in mid 1944. But they never determined the cause. In artillery applications, proximity fuses revolutionized bombardment tactics. Traditional artillery shells using impact fuses only detonated when hitting the ground.

Against troops in trenches or foxholes, impactfused shells were relatively ineffective. The ground absorbed most of the explosion’s force. Proximity fuses detonated shells at optimal height above the ground, typically 20, 30 feet. This created an air burst effect, spraying deadly fragments downward in a conepattern.

Trenches and foxholes that protected against ground burst shells offered no protection against air burst. The first large-scale use of proximity fused artillery came during the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944. German forces launching a massive surprise offensive through the Arden’s forest initially made significant gains against American positions.

American artillery battalions equipped with proximityfused 105 mm and 55 mm shells delivered devastating defensive fire. German infantry accustomed to artillery that they could take cover from found that proximity fused air bursts killed troops in foxholes, behind trees, in buildings. The psychological impact was severe. There was nowhere to hide.

One captured German officer interrogated after the battle reported, “Your artillery has become incredibly deadly. Shells explode overhead without hitting anything. My men cannot take cover. It is as if you have some device that makes shells explode at the worst possible moment.” He was exactly right. Postwar analysis estimated that proximity fused artillery was 5 to 10 times more effective than traditional impactfused artillery against personnel targets.

The same bombardment that previously required 100 shells might achieve equivalent results with 10 to 20 proximity fused shells. The economic and logistical implications were enormous. Artillery effectiveness wasn’t just about killing enemies. It was about ammunition consumption, transportation requirements, and supply chain logistics.

Proximity fuses meant armies could achieve the same effects with a fraction of the ammunition, easing the massive logistical burden of supplying modern military forces. The Germans never developed an equivalent technology despite having access to the fundamental science. Postwar interrogation of German scientists and engineers revealed why Germany had excellent physicists, sophisticated electronics industry, and advanced radar technology.

They had all the pieces needed to create proximity fuses, but they never put the pieces together the right way. German military research prioritized different goals. They focused on rocket technology, V1 and V2 weapons, jet aircraft, advanced tanks, and strategic weapons. Improving artillery fuses wasn’t considered a priority.

German research culture emphasized theoretical perfection over practical implementation. German engineers shown proximity fuse components often dismissed them as crude and inefficient which they were from an electrical engineering perspective. The idea that such primitive devices could be militarily valuable didn’t align with German expectations of technological excellence.

Germany also faced resource constraints. By 1943-44, German industry struggled to produce enough basic weapons and ammunition. Developing and manufacturing sophisticated new fuse technology would have required resources Germany simply didn’t have. Finally, German military leadership didn’t recognize the problem. Proximity fuses solved.

German anti-aircraft defenses relied heavily on high volumes of fire and sophisticated fire control systems. They achieved reasonable effectiveness through different methods, so the need for proximity fuses wasn’t obvious. The Japanese faced similar obstacles. Japan’s electronics industry was less advanced than Germany’s.

Japanese research priorities focused on aircraft, ships, and torpedoes. The resources needed to develop proximity fuses didn’t exist, and the strategic value wasn’t recognized until too late. Both Germany and Japan captured proximityfused ammunition. Both examined them in laboratories. Both recognized the shells used some kind of radio-based mechanism.

Neither successfully reverse engineered the technology before the war ended. The proximity fuse remained Allied exclusive throughout World War II. The full story of the proximity fuse’s development and impact wasn’t disclosed until after the war. The technology had been so closely guarded that even many Allied military personnel didn’t understand how it worked.

When details were finally published in 1945-46, the scientific community was stunned by the achievement. miniaturaturizing a radar system into an artillery shell fuse, making it rugged enough to survive gunfiring, reliable enough for combat use and cheap enough to manufacture by the millions, represented an engineering triumph comparable to any wartime achievement.

The proximity fuse won accolades as one of the war’s most important technologies. Some military historians rank it alongside radar and the atomic bomb in strategic impact. While less dramatic than nuclear weapons, the proximity fuse affected far more battles and saved far more lives. American and British forces fired over 22 million proximity fused rounds during World War II.

Conservative estimates suggest the fuses directly prevented tens of thousands of Allied casualties by improving defensive capabilities against aircraft, V1 weapons, and artillery bombardment. The technologiesinfluence extended far beyond World War II. Postwar proximity fuses became standard in military arsenals worldwide. Modern variants use solid state electronics instead of vacuum tubes, offer greater range and sensitivity, and cost a fraction of 1940s versions.

But the fundamental principle, shells that detect proximity to targets and detonate automatically remains unchanged. Surfaceto-air missiles, anti-aircraft guns, naval weapons, and even some small arms ammunition now use proximity fusing. The technology Merryill Touve’s team developed in 1940 to42 became foundational to modern weapon systems.

The secrecy that protected proximity fuses during the war created interesting historical challenges because the fuses weren’t publicly acknowledged until after victory. Their role in specific battles and campaigns was obscured. Military histories written immediately after the war couldn’t discuss proximity fuses, so they attributed Allied anti-aircraft success to other factors.

Better training, superior tactics, improved fire control. Only decades later, as classified information was declassified and veterans spoke more freely, did historians fully understand how critical proximity fuses had been to Allied victory. The men who developed the proximity fuse received far less recognition than those who worked on more famous projects like the Manhattan project or radar development.

Merldis Tuvi, the physicist who initiated and led the program, remained relatively unknown outside scientific circles. Yet, the proximity fuse arguably had greater immediate military impact than nuclear weapons. The atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended the Pacific War, but weren’t used in combat again.

Proximity fuses were used in every theater of war in hundreds of battles, firing millions of rounds, saving countless lives. The story of the proximity fuse teaches several lessons about innovation and warfare. First, revolutionary advances often come from asking different questions. Everyone wanted better accuracy.

Tuve asked whether accuracy even mattered if shells could be made smart enough to compensate for aiming errors. Second, impossible is often just very difficult. Every expert said miniature radar in artillery shells couldn’t be done. The team did it anyway through persistence, creativity, and refusal to accept conventional limitations.

Third, simple, inelegant solutions that work beat sophisticated elegant solutions that don’t. The proximity fuse of vacuum tubes were crude by electronic standards. They worked anyway and working was all that mattered. Fourth, secrecy can be as important as technology. The proximity fuse remained effective partly because it was effective and partly because enemies never understood it well enough to develop counter measures.

The weapon and its secret were equally valuable. Fifth, the best weapons aren’t always the most dramatic. Nuclear weapons get headlines. Proximity fuses won battles. Both mattered, but in very different ways. Today, the original proximity fuse exists primarily in museums. The National Museum of American History has several examples.

The Proximity Fuse display sits quietly in a corner, a small metal cylinder about the size of a coffee cup, easy to overlook among larger, more visually impressive exhibits. Most visitors walk past without stopping. Those who do stop see a simple object, a metal shell with some primitive looking electronic components visible through a cutaway section.

Nothing impressive, nothing that screams revolutionary technology. The placard explains briefly, “Proximity fuse allowed artillery shells to detonate near targets without direct contact dramatically improved anti-aircraft effectiveness used extensively in World War II. What the placard doesn’t convey is the achievement’s magnitude.

The thousands of hours of research, the hundreds of failed prototypes, the brilliant insights that made miniature radar possible, the manufacturing innovations that enabled mass production, the secrecy that kept enemies blind, the lives saved by shells that exploded at exactly the right moment. It doesn’t convey the image of German engineers holding proximity fuse components in their hands, knowing something remarkable was happening, but unable to understand what, knowing American anti-aircraft fire had become mysteriously lethal, but unable to

determine why. Having the answer literally in front of them and missing it completely. It doesn’t convey the British gunner’s experience loading shells, firing at V1 rockets, watching the shells explode near their targets as if by magic, seeing vengeance weapons tumble from the sky, knowing London was being saved, but not understanding how.

It doesn’t convey Merl Tuve’s satisfaction when the first prototype successfully survived gunfiring, proving the impossible was merely very difficult. or the moment when combat reports showed proximity fuses achieving effectiveness rates that seemed too goodto be true. All of that history, all that innovation, all that impact reduced to a small metal cylinder in a museum display case.

The proximity fuse reminds us that warfare’s decisive technologies aren’t always the most obvious. Not the biggest guns, not the fastest planes, not even nuclear weapons. Sometimes victory comes from making shells smart enough to know when to explode. Sometimes the greatest achievement is invisible. A radio signal bouncing off an aircraft being received, processed, and acted upon in fractions of a second by a device smaller than a soda can, flying through the air at hundreds of miles hour, surviving forces that would destroy any ordinary electronics and

detonating at the precise moment to maximize lethality. The Germans never figured it out. They held the pieces. They examined the components. They knew something extraordinary was happening, but they never understood the magic. And that’s exactly how Merlet and his team planned it.

One physicist’s question, what if shells could sense targets became 22 million rounds that changed warfare forever? The magic wasn’t magic at all. It was physics, engineering, and the refusal to accept that impossible meant impossible. That’s how the proximity fuse shot down 75% of V1 rockets and won battles the Germans never understood they were losing.

News

When 64 Japanese Planes Attacked One P-40 — This Pilot’s Solution Left Everyone Speechless

When 64 Japanese Planes Attacked One P-40 — This Pilot’s Solution Left Everyone Speechless At 9:27 a.m. on December 13th,…

Wehrmacht Mechanics Captured a GMC Truck… Then Realized Germany Was Doomed

Wehrmacht Mechanics Captured a GMC Truck… Then Realized Germany Was Doomed August 17th, 1944. Northern France near Files. The GMC…

They Shot Down His P-51 — So He Stole a German Fighter and Flew Home

They Shot Down His P-51 — So He Stole a German Fighter and Flew Home November 2nd, 1944. 3:47 p.m….

The US Army Couldn’t Break The Nazi Fortress — So A Mechanic Built A Six-Wheeled Rocket Jeep

The US Army Couldn’t Break The Nazi Fortress — So A Mechanic Built A Six-Wheeled Rocket Jeep They say the…

How One Sailor’s Forbidden Depth Charge Modification Sank 7 U Boats — Navy Banned It For 2 Years

How One Sailor’s Forbidden Depth Charge Modification Sank 7 U Boats — Navy Banned It For 2 Years March 17th,…

German mockery ended — when Patton shattered the ring around Bastogne

German mockery ended — when Patton shattered the ring around Bastogne December 22nd 1944 1447 SS Oberg group and furer…

End of content

No more pages to load