It was just a portrait of a Black US Marine and his family — but look more closely at their hands

December 17th, 1945. Camp Llejun, North Carolina. A flashbulb pops in the dim studio, freezing a moment that would change Marine Corps history forever. Second Lieutenant Frederick Clinton Branch stands perfectly still in his crisp uniform. Silver bars gleaming on his shoulders as his wife Camila’s hands tremble slightly, pinning those bars that symbolize so much more than rank.

The photographer steps back, satisfied with the image, but he doesn’t realize what he’s truly captured. In that photograph, their hands tell a story that military records could never convey. Her fingers touching the silver bars, his hands steady at his sides. The first black officer in the United States Marine Corps, and the woman who supported his improbable journey.

No one in the 200 square mile marine training facility knew that this single portrait, this everyday ritual of a wife pinning rank on her husband, would become the visual evidence of a barrier that took 167 years to break. And hidden in plain sight was the silent rebellion few noticed. Their intertwined fingers in the final frame, a gesture strictly forbidden in official military photographs of the era.

The man who would make this moment possible wasn’t born to be a pioneer. He was simply determined to serve his country with dignity even when that country wasn’t prepared to offer the same in return. Frederick Clinton Branch was born in Hamlet, North Carolina in 1922. the fourth son of an African Methodist Episcopal Zion minister.

His childhood unfolded against the backdrop of the Great Depression, where even the most basic needs were often uncertain for black families in the rural South. His parents, like so many of that generation, instilled in him values that would later define his military service, discipline, faith, perseverance, and an unyielding belief that education was the key to advancement.

After completing high school in Mammaran, New York, Branch enrolled at Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte, where the young physics student joined the Kappa Alphasai fraternity and built a reputation as a serious, dedicated scholar. His professors noted his exceptional mathematical mind and precise attention to detail, qualities that would serve him well in the unforgiving environment of officer training.

What Branch could not have known as he walked across campus was that world events were conspiring to pull him from the peaceful pursuit of academic excellence into the crucible of global conflict. As the United States mobilized for war following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the demand for manpower began to reshape long-established racial barriers, though not without resistance.

In May 1943, while studying at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Branch received his draft notice. He reported to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, expecting to join the army like most black drafties of the era. Instead, fate intervened in the form of a personnel officer, who directed him toward a branch of service that had never before accepted men who looked like him.

“You’re going to be a marine,” the officer stated flatly. Branch must have known this was unusual. For 167 years, the entire history of the corps, no black man had ever worn the uniform of a United States Marine. That changed only after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802 in 1941, prohibiting racial discrimination in government agencies, including the armed forces.

Even then, the Marine Corps had dragged its feet until 1942 when mounting pressure from the White House and Elellanena Roosevelt finally forced their hand. Becoming one of the first black Marines meant reporting not to the established training facility at Paris Island, where white recruits went, but to Montford Point, a hastily constructed segregated training camp carved from swampland at the edge of Camp Lejune.

The conditions there were deliberately harsh with inadequate facilities and instructors chosen specifically for their reputation as the toughest drill instructors in the core. The unspoken mission was clear. Make the experience so brutal that these men would quit. Proving what many Marine Corps leaders already believed that black Americans weren’t suited for the elite fighting force.

What they failed to anticipate was the iron determination of men like Branch and the 20,000 other black Marines who would train at Montford Point between 1942 and 1949. They tried to break us. Another Montford Point Marine would later recall. Instead, they made us unbreakable. Branch’s intelligence and education set him apart.

While most black Marines were assigned to ammunition and depot companies, loading and unloading supplies, digging ditches, building roads, Branch’s capabilities could not be so easily dismissed. He completed boot camp with distinction and was assigned as a mortman to the 51st Defense Battalion, one of the two all black combat units formed during World War II.

Yet, despite his qualifications,when Branch first applied to officer candidate school, he was summarily rejected. The message was unambiguous. The Marine Corps might be forced to accept black enlisted men, but the silver bars of an officer were a line they were not yet willing to cross. This rejection might have deterred a lesser man. But Frederick Branch wasn’t fighting for himself alone.

He carried the silent expectations of thousands, those who came before him, those alongside him, and those who would follow. The path forward appeared when Branch was deployed to the Pacific theater. There, amid the brutal island hopping campaign, his intelligence and leadership caught the attention of his commanding officer, a white captain who had the moral courage to see beyond the prejudices of his time.

This officer did something unprecedented. He recommended branch for officer candidate school over the objections of multiple superior officers. If we’re fighting for democracy, the captain reportedly said, “We’d better start practicing it.” While Branch was in the Pacific, a parallel struggle was unfolding on the home front.

His wife, Camila, whom friends called Peggy, maintained a home in Charlotte, and worked to support the war effort like millions of other military spouses. But unlike white military wives, she faced the double burden of racism and separation. When she sent letters to her husband, she could never be certain how long they would take to arrive, if they arrived at all.

Black servicemen’s mail was often delayed or lost by military postal workers who saw no urgency in delivering letters to men they considered inferior. Camila kept every letter Frederick wrote, storing them in a cedar chest alongside newspaper clippings about the Negro Marines and their fight for recognition. She preserved these precious documents even though she couldn’t share them with her neighbors or display them proudly as white military wives could.

The social cost would have been too great in a segregated Charlotte. What neither of them knew as they corresponded across oceans was that the landscape of military race relations was shifting beneath their feet. In April 1944, the performance of black marines at the Battle of Saipan had begun to change perceptions.

There under enemy fire, the men of the Third Marine Ammunition Company had maintained a steady flow of ammunition to the front lines with such dedication that Marine General Alexander Vandergrift was forced to acknowledge, “The Negro Marines are no longer on trial. They are Marines.” Period. Those words represented a seismic shift in the institutional thinking of a military branch that had resisted integration more fiercely than any other.

And while they didn’t immediately translate into equality, they created the narrow opening through which men like Branch might advance. In November 1944, as the war in the Pacific intensified, the Marine Corps reluctantly approved Branch’s application to officer candidate school. He would join a class of white candidates at the Marine Base in Quantico, Virginia, where he would face the most challenging test of his life.

Not just mastering the rigorous curriculum, but doing so in complete isolation. For nine weeks, Frederick Clinton Branch lived as the only black man in a sea of white faces. He ate alone at the messaul, studied alone in his quarters, and faced the silent treatment from fellow candidates who had been raised in a society that taught them black men could never be their equals, much less their superiors.

I knew every eye was watching me. Branch would later tell a reporter from the blackowned Pittsburgh Courier newspaper. Any mistake would be magnified a hundred times. Any failure would be seen as proof that Negroes couldn’t handle the responsibility of command. The pressure was immense.

Every test, every drill, every inspection carried the weight not just of his own future, but of thousands of others who would follow if he succeeded or who would be denied the chance if he failed. The coursework was deliberately grueling. Candidates were expected to master topics ranging from military law to tactical maneuvers, weapons systems to logistics.

Physical training pushed them to the limits of human endurance. Sleep deprivation was a standard tool used to simulate combat stress. For most candidates, the camaraderie of their fellow officers in training provided essential emotional support through these trials. Branch had only his own inner resources and the knowledge that his wife Camila waited for him, believing in his ability to accomplish what no black man had done before.

Through sheer determination, intellectual capability, and unwavering focus, Branch not only completed the course, but excelled. On November 10th, 1945, the Marine Corps’s 170th birthday, Frederick Clinton Branch became the first African-American commissioned officer in the United States Marine Corps. The historical significance of the moment was not lost on the MarineCorps, however reluctant some of its leaders might have been.

A photographer was assigned to capture the traditional pinning ceremony where a new officer’s insignia of rank is affixed to his uniform by someone close to him, typically a parent, mentor, or spouse. For Branch, there was never any question who would pin those silver bars to his shoulders. Camila Peggy Branch had earned the honor through years of support, sacrifice, and belief in her husband when few others shared that faith.

The photographer positioned them precisely according to military protocol, the officer at attention, the wife carefully pinning the bar to his shoulder. But in the last frame, the one that wasn’t supposed to be captured, Frederick and Camila’s hands met in a brief forbidden touch that spoke volumes about their private triumph in this public moment.

To understand the revolutionary nature of that simple gesture, one must comprehend the suffocating racial codes that governed every aspect of military life for black service members and their families. In 1945, public displays of affection were strictly regulated for all military couples, but for black couples, the rules were enforced with particular vigilance.

The image of a black officer being touched tenderly by his wife threatened the carefully constructed narrative of black servicemen as fundamentally different and inferior to their white counterparts. In that single unguarded moment, their fingers intertwined at the edge of the frame. The branches asserted their humanity in a system designed to deny it.

their hands connecting in that fraction of a second represented an act of quiet defiance as powerful as any protest march. The photograph was developed and filed away in military archives where it would remain for decades. A black and white testament to a breakthrough moment in American military history. Its significance would grow with time even as the couple moved forward into a postwar world that remained deeply segregated despite the victories abroad.

After receiving his commission, Second Lieutenant Branch was assigned to Camp Pendleton, California as a training officer. There he faced the delicate and unprecedented challenge of commanding both white and black Marines, men who had been raised in a society that told them a black man could never give them orders.

Branch navigated this minefield with the same methodical precision that had carried him through officer training. He was neither unnecessarily strict nor inappropriately lenient. He simply embodied the Marine Corps standards so completely that to question his authority would be to question the core itself. A white private under his command would later recall, “At first I didn’t know how to feel about having a colored officer, but Lieutenant Branch never gave us a chance to think about his race.

He was too busy making us into Marines.” This was Branch’s subtle genius, redirecting attention from what made him different to what united them all, the shared identity as United States Marines. His commanding officer noted in a fitness report that Branch had overcome the handicap of his race through outstanding performance of duty.

The irony of praising someone for overcoming a handicap that existed only in the minds of those doing the evaluating apparently escaped the officer. But for Branch, such backhanded compliments were the currency of advancement in the segregated military. He collected them and moved forward, keeping his eyes fixed on a future where such qualifications would no longer be necessary.

When the Korean War erupted in 1950, Branch was recalled to active duty from the reserves and promoted to captain, another first for a black marine. Yet despite his proven capabilities, he was still largely limited to training assignments rather than combat command. The Marine Corps might have been forced to commission black officers, but it would be years before they were trusted with the same responsibilities as their white counterparts.

Throughout these professional challenges, the photograph of that pinning ceremony remained tucked away in military archives, seen by few and appreciated by fewer still. Its significance would only be fully understood decades later when historians began reassessing the long struggle for military integration. What makes the image particularly powerful is what it doesn’t show.

The daily indignities the branches endured even after his commissioning. When they traveled together on military business, Camila often couldn’t stay in the same hotels or eat in the same restaurants as the wives of white officers. At official functions, they were frequently seated apart from other couples or excluded entirely under various pretexts.

Their resilience in the face of such treatment was remarkable. Rather than becoming bitter or withdrawing from military society, they maintained a dignity that gradually won respect from even the most prejudiced quarters. They understoodthat each slight they endured with grace created space for those who would follow.

After leaving active duty for the second time in 1955, Captain Branch completed his physics degree at Temple University and began a 30-year career teaching science at Dobbins High School in Philadelphia. There he shaped the minds of generations of students, many of whom never knew they were being taught by a man who had broken one of the military’s most resistant color barriers.

This was typical of Branch’s approach to his historical significance. He never sought recognition or special treatment based on his pioneering status. When a student once discovered his military accomplishment and asked why he never mentioned it, Branch reportedly replied, “Because I was more interested in what you might accomplish than what I already had.

” The branches built a quiet life in Philadelphia centered around family, education, and community service. They raised children who grew up understanding that barriers exist to be overcome, not accepted. They attended church, paid taxes, voted in elections, and lived the thoroughly American life that Frederick had helped defend, but had been denied to so many of their generation.

For decades, the wider world largely forgot about Frederick Clinton branch and his historic achievement. The civil rights movement found new icons and the story of the first black marine officer gathered dust along with the photograph that documented the moment. This began to change in 1995, 50 years after Branch’s commissioning when the Senate passed a resolution to honor his contribution to the integration of the United States Marine Corps.

Two years later, the Marines dedicated branch hall at the officer’s candidate school in Quantico, Virginia, the same facility that had once isolated him as its only black candidate. At the dedication ceremony, an elderly Captain Branch cut the ribbon alongside his wife of 52 years. As photographers captured the moment, someone produced a copy of that original 1945 photograph.

the young left tenant and his wife, their hands connecting in that subtle gesture of triumph and intimacy. The elderly couple looked at the faded image with quiet smiles. “They caught us,” Camila whispered, touching the spot where their fingers met in the photograph. “We weren’t supposed to do that. Some rules,” her husband replied softly, “were made to be broken.

” It was a poignant moment of recognition, not just of the historic milestone the photograph represented, but of the personal courage it had taken to achieve it. As they stood there, surrounded by a new generation of marine officers, including many people of color, the branches could see the fruits of seeds they had planted five decades earlier.

In 2005, just 6 years after Camila passed away, Frederick Clinton Branch died at age 82 following a short illness. He was buried with full military honors at Quantico National Cemetery. His grave marker noting his historic status as the first black marine officer. The obituaries that followed highlighted his military breakthrough, but said little about the photograph that had documented it, or the subtle act of defiance captured in that intertwined touch.

That detail remained largely overlooked until historians examining military integration began studying the visual evidence of these transitional moments more closely. What they discovered in that image was a perfect encapsulation of how progress often occurs through small human gestures within larger institutional changes.

The official narrative was one of the Marine Corps magnanimously opening its officer ranks to qualified black candidates. The reality captured in that photograph was of two individuals asserting their humanity within a system designed to minimize it. Today, that photograph hangs in the National Museum of African-American History and Cu

lture in Washington, D.C., where visitors often pass it without recognizing its significance. It doesn’t have the immediate emotional impact of lunch counter sitins or freedom marches. There are no fire hoses, no police dogs, no crowds of protesters. There is only a young black officer and his wife, hands briefly touching in a moment of shared triumph that would help reshape one of America’s most traditionbound institutions.

Military historians now recognize Branch’s commissioning as a crucial domino in the sequence of events that led to President Harry Truman’s executive order 9981 in 1948, which officially desegregated all the US armed forces. While the Army and Navy had previously commissioned small numbers of black officers, the Marine Corps’s resistance had been total until Branch broke through.

His success proved what should never have needed proving. That skin color had no bearing on leadership ability, intelligence, or courage. Once this artificial barrier fell, others began to crumble as well. The path branch blazed has since been followed by thousands of black marine officers,including Lieutenant General Frank E. Peterson, the first black marine aviator and general, Major General Charles F.

Balden Jr., who became a NASA astronaut and administrator and Lieutenant General Walter E. Gaskin, who commanded all Marine forces in Iraq’s Anbar province during some of the fiercest fighting of the Iraq War. Each of these officers and thousands more owe some portion of their opportunity to that moment captured in 1945 a new left tenant standing at attention as his wife pinned silver bars to his uniform, their hands briefly touching in a gesture that symbolized both personal and national transformation. The story

of Frederick and Camila Branch reminds us that history often turns not on grand gestures or dramatic confrontations, but on quiet moments of human connection and dignified persistence in the face of injustice. Their legacy lives on not just in the institutions they helped change, but in that single photograph that captured both official history and personal defiance in the same frame.

As we look at that image today, the crisp uniform, the proud stance, the silver bars gleaming on his shoulders, we might easily miss what makes it truly revolutionary, their hands briefly touching in a system designed to keep them apart. It was just a portrait of a black marine and his family until you looked more closely at their hands.

Would you have noticed what the photographer caught that day? Would you have recognized the quiet courage it took not just to break the color barrier, but to assert one’s full humanity within it? Comment below and share this story so others remember what courage really means. Not just in moments of dramatic conflict, but in the quiet gestures that change institutions from within.

News

They Mocked His ‘Suicide’ Plan — Until He Blew Up 17 Bridges in Hitler’s Face

They Mocked His ‘Suicide’ Plan — Until He Blew Up 17 Bridges in Hitler’s Face At 0530 on December 17th,…

How One Mechanic’s “Stupid” Cow Paint Job Made His B-17 Unkillable

How One Mechanic’s “Stupid” Cow Paint Job Made His B-17 Unkillable At 0600 on June 8th, 1944, Technical Sergeant…

Miami Hurricanes Cash In On Massive $20 Million Payout, Thanks To Florida State

Miami Hurricanes Cash In On Massive $20 Million Payout, Thanks To Florida State January 10, 2026, 7:16pm EST 219 • By Lou Flavius The…

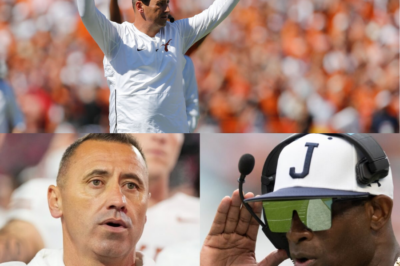

Steve Sarkisian Reacts Quickly After Deion Sanders Raids Texas Roster

Steve Sarkisian Reacts Quickly After Deion Sanders Raids Texas Roster January 10, 2026, 11:57pm EST 89 • By Vipul Dhawas Deion Sanders recruited Liona…

Japan Built An “Invincible” Fortress. The US Just Ignored It

Japan Built An “Invincible” Fortress. The US Just Ignored It At 0730 hours on November 1st, 1943, Lieutenant General Alexander…

German Submarine Tore His Ship Apart — This Captain Sailed 800 Miles With a Massive Hole in the Hull

German Submarine Tore His Ship Apart — This Captain Sailed 800 Miles With a Massive Hole in the Hull At…

End of content

No more pages to load