‘Please Stop—I’m Infected’ German Female POWs Didn’t Expect This From U.S. Soldiers

1944, Western Germany. As Allied forces pushed east and the war began to collapse inward on itself. By late autumn, the roads of Western Germany were crowded with movement that no longer had clear direction. Columns of refugees moved alongside retreating military units. Trains still ran, but without schedules anyone trusted.

Rail lines that once moved coal and soldiers with industrial precision now carried anything that could still be moved. supplies, wounded men, displaced civilians, prisoners, and sometimes nothing but sealed cars rolling without purpose. One of those trains would be found by American soldiers in circumstances none of them would ever forget.

It was early morning when a US infantry patrol came across the train. It stood motionless on a siding outside a small industrial town that had been abandoned days earlier. The station building was empty. The surrounding factories were silent. No guards, no officers, no engine crew. The locomotive sat cold, its fire long dead.

The cars behind it were sealed box cars, wooden freight cars, not passenger coaches. From the outside, the train looked like dozens of others the Americans had already passed. Cargo left behind by a collapsing system. But this one was different. As the patrol approached, one of the men noticed movement through a narrow ventilation slit.

Another heard something faint, too weak to be shouting, too irregular to be machinery, a sound like wood being tapped from inside, then a voice, thin, cracked, female. The lieutenant ordered the men to stop. They listened. From inside, the sealed cars came knocking, then coughing. Then a word repeated again and again in German. Hila, help. The Americans forced the door open.

What they found inside the first car did not look like prisoners in any sense. The men recognized dozens of women were crammed together, collapsed against each other on the floor, on makeshift bedding made from coats and rags. Uh, some were sitting upright but swaying, barely conscious.

Others were lying completely still. The air inside the car was thick with the smell of sickness, waste, and rot. Many of the women did not react when the door opened. Several did, but not with relief. They recoiled. Hands went up instinctively. Some screamed weakly. Others cried. One woman near the door scrambled backward, dragging herself across the floor as if distance alone could save her.

Then one voice cut through the confusion. Bitter stop infid. Please stop. I’m infected. The American soldiers froze. The woman who spoke was young, maybe in her early 20s. Her hair had been cut unevenly, likely by hand. Her face was sunken, skin stretched tight over cheekbones. She pressed herself against the wall of the car, palms raised, shaking.

Don’t touch me, she said again in broken English. Please, I’m infected. Behind her, several others repeated the same word. Infected. The lieutenant ordered his men to step back. In 1944, disease terrified soldiers almost as much as bullets. Typhus, dysentery, tuberculosis, epidemic spread rapidly among displaced populations.

American units had strict orders to isolate suspected cases. Medical officers were scarce, overstretched, and already dealing with outbreaks among liberated prisoners elsewhere. The instinct of the soldiers was clear. Close the door, mark the car, call it in, move on. But as they hesitated, one of the men noticed something else.

The women weren’t attacking them. They weren’t rushing the door. They weren’t even trying to escape. They were begging the Americans not to come closer. That changed everything. The lieutenant stepped forward slowly, raising his hands to show he meant no harm. He asked questions through a German-speaking corporal.

Who were they? Why were they here? Where were the guards? The answers came slowly, haltingly, overlapping as more women tried to speak. They were German civilians, factory workers, clerks, students. Some had been evacuated from cities destroyed by bombing. Others had been arrested for minor offenses. black market trading, refusing labor assignments, criticizing the regime.

A few had been auxiliary workers attached to military units that no longer existed. Weeks earlier, they had been loaded onto trains under guard. Told they were being relocated west away from the advancing front. Then the guards disappeared. The train stopped. The doors were locked from the outside. No food, little water, no medical care.

People began to get sick. First it was diarrhea, then fever, then rashes. Some women developed open soores, others began coughing blood. The strongest tried to care for the weakest, but supplies were gone within days. Clothing was torn into bandages. Snow melt was collected in tin cups when the train stopped briefly at sightings.

One by one, people died. The survivors had stopped counting. The Americans opened the other cars. Each one told the same story. Some were worse. In one car, more than half the occupants were alreadydead, bodies stacked against the walls because there was no space left on the floor.

In another, only a handful were still alive, barely conscious, their breathing shallow and irregular. The soldiers stood in stunned silence. They had seen death before. On beaches, in hedgeros, in burnedout villages. But this was different. There had been no battle here, no resistance, no enemy fire, just abandonment. The lieutenant radioed headquarters immediately.

Medical units were requested. Quarantine protocols were debated. Command wanted to know whether these women were prisoners, civilians, or enemy personnel. No one had an immediate answer. While they waited, the soldiers faced a choice. Leave the women sealed until doctors arrived or risk infection to begin helping.

Now, it was not a heroic decision made with speeches or ceremony. It was a quiet one. One soldier simply stepped forward, removed his gloves, and offered his canteen through the door. Others followed. They did not touch the women at first. Water was passed carefully. Bread rations were broken into small pieces.

Too much food too quickly could kill starved people. The men remembered training about famine victims. Everything had to be slow, controlled. The woman who had first spoken, “I’m infected,” watched as an American medic finally arrived hours later. He wore improvised protective gear and examined her carefully. She was feverish, malnourished, covered in lice bites, but she was not infected with typhus. Most of them weren’t.

The rashes came from malnutrition. The sores from prolonged exposure, lack of hygiene, and untreated injuries. Some had dysentery. A few had tuberculosis. But the fear had spread faster than disease. They had been told by guards, by rumors, by terror, that sickness meant death, that infection meant execution or abandonment.

They believed it. Medical tents were set up near the tracks. The women who could walk were helped out first. Many collapsed immediately once they stood upright. Muscles that hadn’t been used properly in weeks gave out. Some fainted in the snow. Those who couldn’t walk were carried. The Americans moved carefully, methodically, documenting each person, tagging the cars, burning contaminated bedding. The dead were removed last.

The women who survived watched silently as bodies were lifted out. Friends, sisters, strangers who had shared the same floor for weeks. No one cried. They were too exhausted. The survivors were transported to a temporary P and displaced person’s camp under American control. There they were separated by condition, not nationality.

The sick were isolated but treated. The weak were fed gradually. Lice were shaved away. Uh clothing was replaced. For many of the women, this was the first time in months that anyone had spoken to them calmly without shouting or threats. Some of them still didn’t trust it. One woman, when an American nurse reached for her arm to take her pulse, flinched violently and cried out again, “Please stop. I’m infected.

” The nurse paused, smiled gently, and explained through a translator that she was there to help. The woman burst into tears. Word of the train spread through nearby units. Other abandoned transports were found in the following weeks. Some with survivors, many without. Uh, as Germany collapsed, its system simply stopped functioning.

Guards fled. Orders were never delivered. Entire groups were left locked in place, forgotten by a state that no longer existed in practice. For the American soldiers who encountered that train, the memory never faded. Not because of what the women had endured, but because of what they had expected. They had expected cruelty from Americans.

They had expected punishment for being German. They had expected to be left behind again. Instead, they were treated as human beings. Years later, some of the women would tell their families about the moment the doors opened, about the fear of infection, about begging soldiers not to touch them, about realizing slowly that no one was going to abandon them again.

For the soldiers, it was a reminder that war didn’t always end with surrender documents or victory parades. And if you found this story worth remembering, take a moment to like the video, subscribe to the channel, and share your thoughts in the comments below.

News

Germans Were Shocked When One American Soldier Held Off 250 Germans For Over An Hour Alone

Germans Were Shocked When One American Soldier Held Off 250 Germans For Over An Hour Alone January 26th, 1945. 2:20…

Angry NFL Fans Think The Buffalo Bills-Jacksonville Jaguars Playoff Game Has Already Been “Rigged” After Fishy Details Emerge

Angry NFL Fans Think The Buffalo Bills-Jacksonville Jaguars Playoff Game Has Already Been “Rigged” After Fishy Details Emerge January 7,…

Jason Garrett Is Reportedly Being Interviewed By Surprise NFL Team For Their Head Coaching Vacancy

Jason Garrett Is Reportedly Being Interviewed By Surprise NFL Team For Their Head Coaching Vacancy January 6, 2026, 11:02pm EST 1K+ • By Alex…

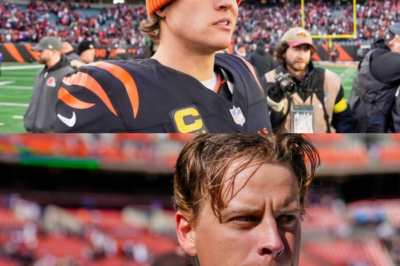

Joe Burrow Reveal Which Teams He Wants To Be Traded To In Cryptic Instagram Post

Joe Burrow Reveal Which Teams He Wants To Be Traded To In Cryptic Instagram Post January 7, 2026, 9:40am EST 11K+ • By Darrelle…

The “Stupid Farmer Trick” That Destroyed Two Panzers in 11 Seconds

The “Stupid Farmer Trick” That Destroyed Two Panzers in 11 Seconds a whole dug with a shovel stopped an entire…

Japanese Infantry Never Expected 12-Gauge American Shotguns in the Assault

Japanese Infantry Never Expected 12-Gauge American Shotguns in the Assault The Pacific Theater, 1942-1945. The dense jungle undergrowth of the…

End of content

No more pages to load