The Army Tried to Kick Him Out 8 Times — This “Reject” Stopped 700 Germans

The US army tried to get rid of this man again and again. Eight disciplinary actions. Eight times his file got thicker. Eight times they thought, “This is it. He’s finished.” But on a summer morning in 1944, the very soldier they wanted out was standing on a bare rise in Normandy, staring down a German force so large it sounded absurd.

700 men behind him. He had 35 paratroopers starving, chewing weeds, pulled from hedge rows just to quiet the cramps, dehydrated, no reinforcements, and the only bridge they could retreat across had just been blown apart. Why American planes? At 7:22, a German officer approached under a white flag not to surrender.

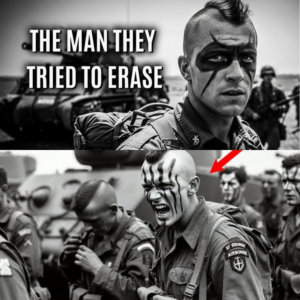

To issue terms from the German perspective, the fight was already over. From the hilltop, surrender meant something else entirely. Disappearing from history as nameless men no one would ever remember. The man in command of those parat troopers was Jake McKnes, 25 years old. Mohawk haircut, and the cruel irony, he had the worst disciplinary record in his entire division.

The German officer laid it out plainly. You’re surrounded. Lay down your weapons. Jake looked down the slope. Then he answered in a way that left no room for misunderstanding. If you want this hill, start climbing. 3 days later, more than 100 German soldiers were dead or wounded. American losses zero. So the question is this. How did a man the US army could barely tolerate become the one who shattered a force 20 times his size? Before Jake Mcnes ever face 700 Germans, he spent years fighting a different enemy.

Not the Vermas, not the SS, the US Army itself. And not because he was a coward, not because he was lazy, not because he didn’t want to serve. Jake had a problem that military systems don’t forgive easily. He could not force himself to obey orders that felt pointless. He wasn’t anti- authority in the childish sense.

He didn’t wake up each morning looking for trouble. He just carried one rule in his head like a weapon from the day he signed up. I follow orders that make sense. Everything else is noise. Jake grew up in Oklahoma during the Great Depression, one of 10 children in a family that survived on whatever the land could provide.

In that kind of household, nobody cared about neatness. Nobody cared about ceremony. If something needed doing, you did it. If you waited politely, you went hungry. He learned to shoot before he learned to drive. He learned to hunt before he could spell half the words in his school books. He learned early that life didn’t reward the people who stood in line and hoped the world would be fair.

By 19, Jake wasn’t working in a store or learning a trade. He was a firefighter running into burning buildings while men his age were still figuring out how to swing a hammer without taking off a thumb. So when Pearl Harbor was attacked, Jake didn’t wait for a draft notice. He volunteered. Not for speeches, not for medals, not for a flag waving dream.

He volunteered for the paratroopers because paratroopers jump behind enemy lines with explosives and Jake liked explosives. The army sent him to Fort Benning, Georgia. New boots, new rules, a will built out of ranks, salutes, routines, and obedience. On his first week, a commanding officer asked him if he understood military discipline. Jake said, “Sure.

” And then almost immediately, he proved he didn’t. That same morning in the mess hall, a staff sergeant took Jake’s butter ration and told him to sit down and shut up. The sergeant laughed. Jake broke his nose. It should have ended his military career in a single punch court marshal. Discharge, Don.

But Jake’s life didn’t run on normal logic. It ran on contradiction because later that same day, yes, the same day, Jake set a base record on the demolition court. The instructors were furious and impressed, and that became the theme of his entire service. Jake refused to call officers sir, unless he believed they’d earned it. He skipped formations. He ignored salutes.

He treated any rule that didn’t help him fight as if it didn’t exist to the army. That wasn’t just disrespect. It was infection. A lieutenant finally snapped at him one day and asked why he couldn’t behave like a normal soldier. Jake answered with a line that spread through the base like wildfire.

I’m here to kill Nazis, not polish boots. The brass hated him for it, but they ran into a problem that terrified them even more than disrespect. Jake wasn’t just difficult. He was too effective to throw away. He shot better than nearly everyone around him. He ran farther than nearly everyone. He could carry 60 lb for miles without slowing down.

And during hand-to-hand training, there were instructors who quietly hoped Jake wouldn’t get paired with them. So instead of kicking him out, the army tried something unusual. They isolated him. They gave him his own small corner of the 101st Airborne, his own platoon space, his own barracks, not as a reward, more like quarantine. The idea was simple.

Keep him away from the restof the division so his attitude didn’t spread. And that’s when the army made the mistake that created a legend. Because once Jake was isolated, the system began doing something it didn’t even realize it was doing. Every time another troublemaker appeared, Nebler, a defiant recruit, a brilliant soldier who couldn’t play nice, new officers faced the same dilemma.

The man was too talented to discharge, but too wild to place with normal troops. A tired officer sighed, and the same sentence started appearing again and again. Send him to Mochnness. At first it was punishment. Then it became a pattern. Eventually it became a pipeline. Within months Jake had collected a dozen men who didn’t belong anywhere else.

A Pennsylvania coal miner built like industrial machinery whom once got into a fight with three military policemen at once over a poker game and broke all three of their noses. No weapons, no warning, three broken faces. And somehow he was also the best marchman in the entire 101st. A New York immigrant who spoke four languages were English, Italian, French, German, Hoon, ran a black market ring selling army supplies to civilians.

On paper, he belonged in a cell. In practice, he could interrogate prisoners better than officers twice his rank. So, they sent him to Jake, a demolition fanatic from Tennessee with the curiosity of a scientist and the judgment of a 10-year-old whom blew up a latrine, not out of anger and not by accident, but because he wanted to see what the explosion pattern looked like.

The army didn’t even yell at him. They looked at his report, looked at his skill set, and transferred him to Jake, a Chicago street fighter who got into 14 fist fights during basic training. He won all 14. The instructors stopped trying to fix him and did the only thing the system knew how to do with people like that.

Send him to Mchess Individually. They were headaches. Lawsuits waiting to happen together under Jake. They became something else. A pack. Jake didn’t train them like parade soldiers. He trained them like predators. No polished boots, no perfect ranks, no pointless drills, no shiny ceremonies. They ran farther than any other platoon.

carried more weight, fought harder during sparring, shot until their shoulders achd. Other units started timing themselves against Mchess’s men just to see if they could keep up. Jake’s platoon finished at the top in marksmanship, demolitions, endurance, and hand-to-hand combat. The only category they consistently failed was uniform inspection because none of them cared.

Officers argued about them in the messaul. Some wanted them court martial, some wanted them studied, but the numbers wouldn’t lie. This platoon, but this trash pile of rejects the army didn’t know where to put was outperforming everyone. And Jake understood why. Obedience and discipline aren’t the same. He told them obedience is doing exactly what you’re told.

Discipline is doing what needs to be done. He didn’t want obedient men. He wanted men who could crawl through mud without freezing, move without being heard, shoot straight when their hands were shaking, improvise when plans collapsed and orders stopped making sense. Men who wouldn’t panic when the world broke because Jake had a belief that the army didn’t like hearing out loud.

The battlefield doesn’t reward perfect soldiers, it rewards survivors. And without realizing it, the army had built the perfect team for the kind of war it was about to throw them into. A war where planes exploded in midair. Where paratroopers landed scattered miles apart. Where bridges vanished in smoke because someone upstream didn’t get the message.

Where supply lines failed, maps lied, and the only thing left was instinct. The officers at Fort Benning thought they were burying their problem in a corner. They didn’t know they were building a weapon. And very soon that weapon was going to be dropped into Normandy and point it straight at a force 20 times its size.

For most soldiers, combat begins when the shooting starts. For Jake Magnus and his men, it began in the air. Inside a vibrating metal tube, flying straight into darkness. On the night of June 5th, 1944, the filthy 13 climbed aboard their C-47 transport. engines drone low and steady, the kind of sound that sank into your chest and stayed there.

Jake stood near the door. His head was shaved into a sharp mohawk, white war paint cut across his cheeks, stark against the dim red light inside the aircraft. His men look nothing like parade soldiers. They look like hunters preparing for a night kill. No jokes, no bravado. Right before takeoff, Jake gave them one instruction.

Once we jump, he said quietly. You stop being who you were. You become what the mission needs. At 11:47 p.m., the plane lifted off the runway and climbed into the black sky over the English Channel. For nearly an hour, the flight was smooth. Too smooth. Men sat in silence, hands resting on their gear, minds running through checks they would neveradmit out loud.

Then the French coast appeared below them, and the sky exploded. At 1:23 a.m., oh, German flack batteries opened fire. First a few bursts, then dozens, then hundreds. White flashes tore through the darkness as 88 mm shells detonated around the formation. The aircraft shook violently. “Hook up!” the jump master shouted. The red light glowed near the door.

The plane lurched again, hotter this time. Then without warning, everything turned white. At 126 MIR, an 88 mm shell tore into the aircraft’s fuel tank. The explosion ripped through the fuselage. Fire flooded the cabin. The tail section tore away. Men who weren’t clipped in were thrown into open air like debris.

The plane stopped being a plane. It became wreckage. Jake was standing in the door when the blast hit. The force hurled him backward into the night. His static line snapped tight, ripping his parachute open. W not cleanly. One panel was on fire. Others were shredded by flack.

He spun violently, dropping fast, unable to steer, plunging straight toward a flooded marsh below. He hit the water hard. The impact knocked the air from his lungs. His heavy gear dragged him under instantly. The harness wrapped around his legs like vines. Most paratroopers who landic like that drowned in seconds. He forced his knife free, cut the tangle straps, and kicked upward through cold black water.

He broke the surface, gasping just as flaming debris from the destroyed aircraft splashed into the marsh around him. He was alive, barely alive. The night around him was chaos. Burning planes spiraled down. Machine gun fire cracked through hedgeros. Explosions echoed across Normandy. Jake didn’t stop to take it in.

He checked his rifle soak, but functional. Then he moved for hours. She crawled, sprinted, and cut through hedges. Moving by sound and instinct, he searched ditches, fields, tree lines. One by one, he found survivors. Jack gone. Alishwitz. Nine men total. Four were dead. Jake gathered the living in a shallow ditch. Faces stre with mud and smoke.

War paint half washed away. Then he gave them their orders. We take the bridge at Chef Dupont, he said. We hold it. No Germans get through. Intended the area. Jake had nine men. He didn’t hesitate. We attack anyway at 6:34 a.m. The tiny group began hunting through the hedros. They ambushed patrols, struck supply lines, vanished before the enemy understood what was happening.

The Germans never realized they were being attacked by fewer than 10 men. Scattered American paratroopers from other units began linking up. Nine became 15. 15 became 25. By late morning, Jake had 35 men under his command. At 11:00, after a string of fast ambushes and brutal confusion, Jake’s group captured the bridge at Chef Dupont.

They had done the impossible and then the impossible turned on them at 4:43 p.m. American pay 47. Thunderbolts screamed overhead. Jake’s men waved helmets, shouted, signaled. The planes circled once, then they dropped their bombs. Acting on outdated orders, American pilots destroyed the very bridge Jake’s men had risked their lives to take.

The bridge collapsed into the river in a roar of smoke and fire. Jake watched it fall, then he laughed, not because it was funny, because it was exactly the kind of mistake he expected. His men stared at him, stunned. Jake wiped mud from his face and explained calmly. They were cut off. No bridge, no reinforcements. Hundreds of Germans regrouping across the river. There would be no retreat.

There’s only one move left, he said. We turned the high ground into a fort and studied the terrain. What he saw wasn’t dramatic. It was mathematical. Three narrow approaches led up the slope. Natural funnels between trees, hedgeros, and embankments. Any force attacking uphill would be forced to bunch together. Jake didn’t need a map.

He didn’t need a briefing. He placed his 230- caliber machine guns where their fields of fire overlapped. He positioned his best riflemen in elevated positions with clear sight lines. Their instructions were simple. Kill the leaders first. Officers, Nikos, cut the head off the snake. He placed bar gunners to suppress enemy machine gun teams and mortars.

do the only real threats to the position, ready to hit any breakthrough instantly. 35 men starving, dehydrated, exhausted, but perfectly placed. On the morning of June 7th, German scouts spotted American paratroopers dug in on the ridge. They reported back on June 8th, probing attacks began. Small groups testing the slope.

Jake’s men killed every one of them. No wasted rounds. The real attack came the next morning at 7:22. And on June 9th, a German officer rode forward under a white flag. Not to surrender, to demand it. He explained the situation calmly, almost politely. Jake had 35 men. He had 700. He had machine guns, artillery, water, supplies, reinforcements, common sense. All pointed one way.

Jake listened at the le man finished. Then he pointed at the slope behind him. If youwant this hill, he said, “Start climbing.” The officer blinked, turned, and signaled the attack. At 9:14 a.m., the first wave began. 200 German infantrymen advanced uphill in tight formation. Jake raised his hand.

He waited closer, closer. When the Germans hit the choke point and packed together, Jake dropped his hand. Fire. The hill erupted. Machine guns tore through the front ranks. Riflemen fired with brutal precision. Men fell in heaps. The slope offered no cover. The wave collapsed in minutes. Jurro. And that was only the beginning.

Because the Germans were about to learn something the US army had already discovered the hard way. You couldn’t break Jake Magnus by throwing rules or numbers at him. You had to survive his system. And they were about to test it again. Wave 1 had failed faster than the Germans expected. From the valley floor, officers watched their men retreat downhill in shock, wounded, dragging, wounded, formations shattered, confidence leaking away with the blood soaking into the grass.

They had assumed the Americans would break. They always did when the numbers were this bad. But something about the hill was wrong. It had been controlled, measured, almost surgical. Jake saw the hesitation ripple through the enemy lines. He didn’t celebrate it. He exploited it. Relo, he told his men quietly. They’ll be back.

They were late that morning. The Germans adjusted. Wave two came with mortars. Shells arc high and slammed into the forward slope of the hill, ripping trees apart and blasting dirt skyward. Explosions echoed like thunder, shaking the ridge. Shrapnel whine through branches. To an observer, it looked devastating. To Jake, it was mostly noise.

He had positioned his men just behind the crest of the hill law in a reverse slope. The terrain absorbed the blast. The hill itself became armor. When the barrage stopped, another 200 German infantry advanced uphill. Jake waited again. They reached the same funnels, the same narrow approaches, the same blind spots, and again, American guns opened.

The second wave lasted barely 5 minutes. Jake’s casualties still zero. By early afternoon, German commanders were furious. They brought artillery. Heavy shells slammed into the hillside, tearing chunks of earth free, splintering trunks, collapsing shallow foxholes. Dirt rained down. The ground trembled under every impact.

Jake’s men stayed flat. They didn’t run. They didn’t return fire. They waited because artillery looks terrifying. Wood only works if it can hit what it’s aimed at. and Jake had made sure it couldn’t. When the shelling lifted, two Panzer eye tanks rolled forward. Steel monsters grinding up the narrow road below the ridge.

Infantry clustered behind them, using the armor as moving cover. Jake watched through binoculars. He knew what his men didn’t have. No bazookas, no anti-tank guns, no explosives capable of cracking armor. But he also knew what the Germans didn’t have. Options. The tanks were trapped by the terrain. The road was a narrow defile between hills.

If the armor stayed on it, the guns couldn’t elevate high enough to hit Jake’s positions. If they left it, they’d sink into mud and become immobile targets. Jake issued a simple order. Ignore the tanks. His men hesitated. “Kill the infantry,” Jake added. When the tanks reached the choke point, American machine guns open.

German infantry fell instantly. Caught in the open with no cover and nowhere to run, the tanks rumbled forward alone, blind and unsupported, firing uselessly into dirt and trees they couldn’t reach. After 30 minutes of thunder and frustration, both panzers backed down the road and withdrew. The hill still stood. Jake’s men were still alive.

German casualty continued to climb. By nightfall on June 9th, the Germans had failed five separate attacks. Over 100 men were dead. Hundreds more were wounded. Jake’s losses, zero. Night settled over the battlefield like a lid. Smoke hung low. Wounded Germans groaned in the brush below. Crows circled overhead, already waiting.

Jake’s men stayed silent in their shallow positions. They couldn’t move. They couldn’t recover bodies. They couldn’t risk a sound. They hadn’t eaten properly in days. Their tongues were dry. Their stomachs cramped. Hands shook. Not from fear, but dehide age. But the hill gave them one advantage the Germans didn’t have. Quiet. Medics moved. Stretchers. Equipment clanked.

Orders echoed uselessly in the dark. Jake whispered to his men. Listen. They’re tired, too. That was enough to get them through the night. At first light on June 10th, the Germans tried one last approach, a heavy mortar bombardment, followed by simultaneous pushes on all three approaches. This time they advanced carefully.

Fire and move, spacing out, avoiding bunching. Jake let them come. It didn’t matter. Once they reached the folds of terrain Jake had memorized, the American guns opened again. The funnels did their work. German soldiers dropped in clusters, 40, 50 more down. Jake’scasualties still hadn’t changed. He ordered a final, desperate charge.

Hundreds of men surging uphill at once, screaming, firing wildly, trying to overwhelm the position by sheer mass. It was chaos. It was brutal, and it was exactly what Jake had been waiting for. “Hold,” he whispered. The hill exploded with fire. Machine guns turned the choke points into blenders.

Bodies piled so quickly the dead became obstacles for the living. Men tripped, fell, crawled, screamed. Some dropped rifles and ran. Some charged blindly with bayonets shaking in their hands. None of it worked. Jake’s 35 men fired with cold precision. A man who had passed hunger and fear and entered something sharper. The charge collapsed.

Hours later, a runner approached under another white flag. A second demand for surrender. Jake didn’t come down the hill. He told the messenger. Tell your commander we’re still here. The message was delivered and understood. At dawn, American reinforcements from the 82nd Airborne finally broke through. They climbed the ridge, expecting carnet.

What they found were 35 filthy starving paratroopers still standing, rifles loaded, eyes locked on the approaches. A relief officer asked for Jake’s casualty count. “Zero,” Jake said. The officer blinked. “Zero,” Jake repeated. But if you brought food, we’ll take it. The impossible had happened. But the war wasn’t finished with Jake Mcnes.

6 months later, winter would close in around a town called Bastonia. And the army once again would face a problem no rubble could solve. This time they wouldn’t try to get rid of Jake. They would point him straight at the crisis and hope he did what he always did best. 6 months after Normandy, the war came back for Jake Magnus in a different shape.

This time it wasn’t a hill, it was a city. In mid December 1944, the Germans launched their last major gamble in the west. A massive armored offensive smashed through the Ardan’s forest, punching holes in thin American lines and driving hard toward the Moose River. History would call it the Battle of the Bulge. For the men inside it, it felt like the end of everything.

At the center of the chaos set a small Belgian town named Bastona. Seven roads ran through it. Whoever held Baston controlled movement across the entire sector. Lose it and the German advance could split Allied forces in half. So the Germans surrounded it fast. By December 18th, more than 11,000 American troops, most of them from the 101st airborne, for completely encircled.

No open roads, no fuel, no winter clothing, no medical supplies, food counted by scraps, ammunition counted round by round, snow pile knee deep, temperatures dropped below freezing. Wounded men lay wrapped in blankets because medics had run out of bandages. If Baston fell, the war in Europe would stretch on for months. The army needed a miracle.

Instead, they got Jake. The only way Bastona could survive was through the air. Small elite teams, Pathfinders, had to jump ahead of supply aircraft and set up radio beacons to guide resupply planes through fog, flack, and snowstorms. It was the most dangerous jump assignment in the entire theater.

Blind jumps, no drop zones, no clear visibility, anti-aircraft fire everywhere. Most officers didn’t even call it a mission. They called it a death sentence. The call went out. volunteers only. Jake didn’t step forward. He leaped on December 18th at 3:47 a.m. Jake and nine other Pathfinders boarded C47 transports before takeoff.

The pilot turned toward them voice tight. Worry visibility is zero, he said. Flack is heavy. We can’t see the drop zone. He paused. Jake shrugged. We’ve survived worse. The pilots stared at him. Jake wasn’t joking. Hours later, the plane reached Basau, or what should have been Basau. The city was completely swallowed by fog, smoke, and falling snow.

There was no horizon, no landmarks. Just white emptiness. I can’t see the ground. The pilot shouted. The jump master lit. We go anyway. Jake stepped out into nothing. No sense of falling, no sense of direction, just cold white silence swallowing him whole. Then the ground hit him like a fist. He rolled, stood, and realized he had landed inside American lines.

Soldiers stared at him in disbelief. Who the hell jumps into Baston right now? Jake brushed no from his jacket. Any idea where the Germans are? The soldier pointed slowly in a circle. All around us. Jake nodded. Good. saves us time. Finding his men in a shattered city was harder than the jump itself. Artillery crashed into buildings.

Smoke clogged the air. Other pathfinders had scattered. Some had landed outside the perimeter. Some hadn’t landed at all. Jake refused to accept that. For 2 hours, he moved through ruined streets, ducking fire, searching basement, barns, snow banks. He found one man crawling through drifts, another limping through smoke with a broken ankle.

By nine falls, Jake had gathered eight of the 10. Two were dead. Eight would have to be enough. Jake split them into twoteams, east and west sides of the city. They set up radio beacons inside shattered buildings on rooftops behind frozen wreckage. If the Germans triangulated the signals, artillery would erase them in minutes.

So the teams bounced signals back and forth, constantly shifting locations. It was threading a needle in a hurricane at 1017 ammon. Jake made the first call. Bust don to ally command. We are surrounded. We are holding. Request immediate resupply. The reply came faster than expected. Supplies and route.

The first say 47 punched through the clouds, flying so low the treetop shook. German flack erupted instantly. Shells burst around the plane, but the pilot held course and kicked supply bundles out of the bay. Food, ammunition, medical gear. The bundles landed inside American lines. Jake exhaled. It worked through the night, through artillery, through snowstorms.

Jake and his team stayed awake, adjusting signals, relocating beacons, dodging bombs. Planes came in so low that soldiers could see frost forming on the wings. By December 20th, something impossible had happened. Thousands of pounds of ammunition, food, medicine, winter clothing. Thanks to Jake, the 101st Airborne kept fighting.

They refused to surrender. And when General Patton’s tanks finally broke through on December 26th, Baston was still standing. Jake received no medal, no ceremony, no public credit. Pathfinder operations were classified, but 11,000 men were alive because he had jumped into a city that everyone else believed was already lost.

And once again, the army learned the same lesson it never seemed to remember. You don’t put a man like Jake Mcnes behind a desk. You point him at a problem and watch it disappear. When the guns finally went quiet in Europe, Jake Mocknes didn’t feel relief. He felt exposed. For four years, his world had been simple in the only way war ever is. There were problems.

There were enemies. You identified them, moved toward them, and made them stop. After Germany collapsed in May 1945, Jake didn’t come home as a hero. He wasn’t paraded. He wasn’t promoted. He wasn’t given speeches or handshakes. The army sent him back into Germany for occupation duty for the first time since he volunteered.

Jake wasn’t fighting, and that was the problem. Watching instead of acting. It meant being surrounded by reminders of a war that had taken everything and being told to behave as if none of it mattered anymore. Jake didn’t know how to do that. He and the surviving members of the filthy 13 were assigned to patrol former Nazi estates scattered across the countryside.

Properties filled with looted wealth, art, jewelry, fine liquor, raceh horses. One estate belonged to Hermman Guring himself. Inside were cabinets of priceless alcohol, silk drapes, gold fixtures, paintings torn from museums across Europe. Jake and his men did what men who had cheated death for years often do when the danger finally stops.

They drank Garing’s liquor straight from the bottle. They rode his horses across open fields. They staged a makeshift rodeo in the courtyard of a palace built by a regime that no longer existed. Jake wasn’t celebrating victory. He was bleeding off tension he didn’t yet understand. She laughed easily. She wasn’t afraid of him.

She didn’t ask questions he didn’t want to answer. Later, he learned her father had been the local head of the Hitler youth. Jay just laughed after years of killing men in uniforms. The lines no longer made sense to him. Enemies, allies, guilt, innocence. Not long after, the army finally decided it had had enough. Jake was sent back to the United States for medical evaluations.

His body had been running on adrenaline and instinct for years, and now the cracks were impossible to ignore. While recovering, he got into one last altercation with military police. This time, he didn’t throw punches. He issued a promise. Once he was a civilian, he said he’d come back and settle things properly. That was the final straw.

The army didn’t court marshall him. They didn’t punish him. They simply let him go. Honorable discharge, 3 years, 5 months, 26 days of service, four combat jumps, hundreds of confirmed kills. The army didn’t know whether to shake his hand or feel relieved that he was finally gone. Jake didn’t care. He was finished.

He went home to Oklahoma and almost immediately the war followed him. There were no planes falling out of the sky anymore. No machine guns, no flack, no hills to hold. But there were nights. There were memories that didn’t wake for permission. Faces, sounds, smells that came back without warning. Jake drank, not to celebrate, to quiet the noise.

Alcohol blurred the edges. It softened the sharpness of memories. It made sleep possible. Even when sleep brought nightmares of burning aircraft and frozen ground, they wanted him to be normal. a husband, a neighbor, a man who talked about the weather and the price of gas. They didn’t know that Jake had spent years as a weapon, and weaponsdon’t shut off easily.

His life spiraled until 1951. One night, drunk and reckless, Jake wrapped his car around a telephone pole at high speed. The impact was so violent, doctors later said he should have died instantly. Instead, he woke up in a hospital bed 3 days later. His skull fractured, rips broken, lungs bruised. For the first time since the war ended, Jake was forced to stop.

Lying there, unable to move, staring at a ceiling that didn’t explode or burn. He saw himself clearly. He had survived a plane exploding in midair. He had survived drowning in a flooded marsh. He had survived holding a hill against 700 men. He had survived Baston. And now he was killing himself slowly. That night, Jake made a decision. It wasn’t dramatic.

It wasn’t spiritual. There were no visions. He simply thought, “If I’m still alive, maybe I’m supposed to do something better than this.” He quit drinking. Cold, immediate, permanent. 6 months later, he married a woman named Mary Catherine. She knew he had served. She didn’t know the details. Jake never told her.

He didn’t want his children growing up thinking war was heroic. He didn’t want them admiring violence or imagining killing as something noble. So he built a different life. He worked at the Panka City Post Office, sought letters, sold stamps, coached little league. He raised three children who had no idea their father had once stood on a hill in Normandy and told 700 men to come and take it.

For 40 years, Jake McKnes disappeared into normal life. No medals on the wall, no stories at dinner, no reminders of the man he had been named. And that was exactly how he wanted it. Jake Mcnes died in 2013 at the age of 93. To his coers, he was the friendly man behind the counter. To his neighbors, he was the quiet guy who never caused trouble.

To history, he was nearly invisible. But here is the truth. The Y army tried to throw Jake Machnice out eight different times and every time they failed, history bent slightly. If he hadn’t survived that burning plane, if he hadn’t held that hill against impossible odds, if he hadn’t jumped into Baston and guided 247 supply drops, thousands of men would not have made it home.

Jake never bragged about any of it because to him, war wasn’t glory. It was something you endured, something you survived, something you hoped the next generation would never have to understand. He wanted to kill Nazis, eat breakfast, and go home. He did all three. If you’re still listening, you’re doing something Jake never asked for. You’re remembering him.

Men like Jake didn’t fit the mold. They broke rules. They caused problems. They made commanders uncomfortable. But when the world collapsed, when plans failed, bridges vanished, and numbers stopped making sense, they were the ones still standing. If someone in your family served, or if you’ve heard stories that never made it into textbooks, leave a comment and share them.

Every comment keeps stories like this alive. And sometimes that’s the only monument men like Jake ever wanted. Jake Mcniss never wanted to be remembered. He didn’t want medals on a wall. He didn’t want strangers shaking his hand. He didn’t want his children growing up believing war was something to admire. He wanted breakfast. He wanted to go home.

And yet, history keeps pulling men like him back into the light. Because wars aren’t decided by perfect soldiers and clean paperwork. They’re decided by people who keep moving when the plan collapses, who think clearly when numbers say they should be dead, and who do the job even when no one is watching.

The US Army tried to throw Jake away eight times. Every time they failed, more men survived. And if there’s one lesson in his story, it’s this. Victory doesn’t always come from discipline. Sometimes it comes from the people who refuse to break when everything else does.

News

Donte DiVincenzo Delivers Perfect Message on Wolves’ Mindset After Hot Start

Donte DiVincenzo Delivers Perfect Message on Wolves’ Mindset After Hot Start January 9, 2026, 12:06pm EST • By Ayushi Bhardwaj Donte DiVincenzo…

They Laughed at Liberty Ships as ‘Ugly Ducklings’ — Until US Launched 2,700 in 4 Years

They Laughed at Liberty Ships as ‘Ugly Ducklings’ — Until US Launched 2,700 in 4 Years September 17th, 1941. The…

The Day America’s Crudest Locomotive Proved It Could Carry An Army Into Germany

The Day America’s Crudest Locomotive Proved It Could Carry An Army Into Germany September 3rd, 1944. Eboo Junction, South Wales….

John Wayne received the letter from his teacher and did something that no Hollywood star would do today

John Wayne Received This Teacher’s Letter And Did Something No Hollowood Star Would Do Today March 1961, a school teacher…

‘Please Stop—I’m Infected’ German Female POWs Didn’t Expect This From U.S. Soldiers

‘Please Stop—I’m Infected’ German Female POWs Didn’t Expect This From U.S. Soldiers 1944, Western Germany. As Allied forces pushed east…

Germans Were Shocked When One American Soldier Held Off 250 Germans For Over An Hour Alone

Germans Were Shocked When One American Soldier Held Off 250 Germans For Over An Hour Alone January 26th, 1945. 2:20…

End of content

No more pages to load