The Surprising Reason This Aircraft Survived 20 Enemy Hits

Tunis, North Africa, February 1, 1943. 26,000 ft. The sky over the Mediterranean is a blinding deceptive blue. It is cold, 40° below zero. But inside the B17F fly Flying Fortress, All American, the air is hot with the smell of cordite and fear. Lieutenant Kendrick R. Bragg wrestles the yoke. He is 24 years old, a former college football player with hands that can crush an apple.

Right now, he needs every ounce of that strength just to keep the 30 ton bomber level. They have just dropped their payload on the German-h held docks of Tunis. The flack was heavy, black blossoms of steel that rattled the aluminum skin like hail on a tin roof. But flack is impersonal. Flack is a roll of the dice.

What is coming at them now is personal fighters 12:00 level. The call comes from the bomber deer in the nose. Bragg looks up. He sees them. Two Messersmidt BF 109s, yellow-nosed predators from the elite JG77. They are setting up a head-on pass. This is the most terrifying tactic in the Luftwaffa’s playbook. The closure rate is over 600 mph.

The German pilots are aiming directly for the cockpit glass. It is a game of chicken played with 20 cannons. The story you are about to hear defies the laws of aerodynamics. It is studied in engineering schools to this day as an example of impossible redundancy. If you want to see the actual photos of this miracle and hear more stories of survival that shouldn’t have happened, hit that like button and subscribe.

You won’t believe your eyes. The lead German fighter opens fire. Tracers zip past Bragg’s canopy. He holds the formation steady. He cannot flinch. If he breaks formation, the defensive box collapses and they all die. The German pilot presses the attack. He is brave, perhaps too brave.

He holds his line until the last possible fraction of a second. Then disaster. The German plane is hit by defensive fire. It rolls inverted. The pilot loses control. The Messers traveling at 350 mph doesn’t dive away. It skids. It skids directly into the all-American. There is a sound like the world cracking in half.

A deafening metallic crunch that vibrates through the soles of Bragg’s boots. The B17 lurches violently upward, then shutters as if it has hit a brick wall. Bragg fights the controls. Report crew check in. What happened? The radio is chaos. We’ve been hit. The tail. The tail is gone. Bragg looks back over his shoulder, but he can’t see the tail section from the cockpit.

He feels the aircraft wallowing. The control cables are slack. The nose wants to pitch down. He trims it back, sweating. Navigator, go back and check the damage, Bragg orders. The navigator, Lieutenant Godfrey, unbuckles and crawls through the bomb bay. He opens the rear hatch. He looks out. He freezes. He scuttles back to the intercom.

His voice is high, tight, bordering on hysteria. Skipper Godfrey says, “The tail isn’t gone, but it should be.” What do you mean? The fighter. It sliced us. The fuselage is cut almost all the way through. The tail is hanging on by a strip of metal. It’s swaying skipper. It’s waving in the wind. Bragg tries to process this.

The Messormid’s wing had acted like a guillotine. It had sliced through the rear fuselage of the B17, cutting through the heavy lines, the stringers, the skin. It had severed the left horizontal stabilizer completely. The tail section, the massive vertical fin, the rudder, the rear gunner’s position, is physically disconnected from the rest of the plane, save for a few inches of aluminum flooring and a single bent lingerine on the top right side.

By all the laws of physics, the tail should have snapped off the moment the slipstream hit it. Without the tail, the B17 would pitch forward into a terminal outside loop, snapping the wings off and disintegrating in seconds. But it hasn’t snapped yet. Is the gunner still back there? Bragg asks. Yes, Sam is back there. He’s trapped.

He can’t crawl forward because the floor is gone. Tail gunner Sam Saralace is sitting in an island of aluminum, isolated from the world. He looks forward and sees daylight where the fuselage used to be. He sees the Mediterranean Sea 26,000 ft below through a gaping hole in the aircraft’s spine. Brag grips the yolk. He feels the tail swaying.

Every time he touches the rudder pedals, he feels the vibration travel up the spine of the plane. It feels like a loose tooth ready to fall out. Don’t move, Bragg tells the crew. Nobody move. Nobody sneeze. We have to keep her steady. He looks at his instruments. He is 300 miles from their base in Biscra, Algeria.

He has to cross the sea. He has to cross the mountains. And he has to do it in a plane that is held together by little more than hope and a few rivets. But Bragg doesn’t know the real reason the plane is holding together. It isn’t just luck. It is a specific surprising engineering principle that Boeing unknowingly designed into the B17.

A principle that is currently fighting a war against gravity at 26,000 ft. Theplane is flying because it is a bridge. The B17’s fuselage is not a simple tube. It is a truss structure built with triangular bracing similar to a suspension bridge. Even though the main structural members, the lingerins are severed on three sides, the load is being redistributed through the remaining diagonal braces.

The tension is immense. The metal is groaning. The top spar is under thousands of pounds of tension while the bottom skin is gone. Bragg gently eases the throttles. He needs to slow down to reduce the aerodynamic pressure on the tail. But he can’t slow down too much or the tail will lose authority and the nose will drop.

He has to fly in a terrifyingly narrow window, 150 mph, no sudden movements, no turbulence. And then he sees the second wave of German fighters. They are circling. They see the crippled B17. They see the daylight showing through the fuselage. They see the tail wagging like a dog’s tail. They are predators and they know a wounded animal when they see one.

The German pilots of JG77 are confused. They drift alongside the all-American. They fly close, so close that Bragg can see the pilots turning their heads to stare. They are looking at the damage. From the German perspective, it looks impossible. The entire rear section of the bomber from the waist windows back is crooked.

It is twisted 5° to the left. The fuselage looks like a piece of paper that has been torn halfway across and left dangling. Why isn’t it falling? One German pilot flying a BF 109 slides in for a finishing pass. He intends to put a burst of 20 cannon fire into the wing route and end the misery. Gunners hold fire. Brag orders don’t shake the ship.

The recoil of the 050 caliber machine guns would create a vibration that could snap the final strip of metal holding the tail. They are defenseless. They have to rely on the enemy’s confusion. The German pilot lines up, but he hesitates. He sees the tail section swaying in the slipstream. He realizes that if he shoots the bomber, it won’t just crash.

It will disintegrate and the debris field will be instantaneous and massive. He is too close. If he blows it up, he will fly right into the cloud of shredding aluminum. The German pulls up. He flies alongside the cockpit. He salutes. It is a gesture of respect or perhaps disbelief. He banks away and heads for home. The other fighters follow.

They figure the B17 is dead anyway. No plane that damaged can make it back to Africa. Gravity will do the work for them. Brag is left alone in the silence of the high altitude. Okay, Brag whispers. They let us go. Now we just have to fly. He begins the descent. This is the most dangerous part. As the air gets thicker, the drag on the tail will increase.

The turbulence from the mountains will batter the airframe. Parachutes. Brag says, “I want everyone ready to bail out except Sam. Sam, you stay put. I ain’t going nowhere, Skipper.” Sarpalis cracks over the intercom. It’s a long step down. Brag feels the yolk trembling. The control cables for the elevators run along the top of the fuselage.

the only part that is still intact. If that top lingerine snaps, he loses pitch control. The nose will drop and they will bunt into a supersonic dive that will tear the wings off. He has to keep the tail flying. He discovers a strange aerodynamic phenomenon. If he keeps the speed exactly at 140 m, the air flow over the fuselage creates a low pressure area that essentially sucks the tail section upwards, helping to support its weight.

The wind is acting as a splint. They cross the coastline of Tunisia. The air is bumpy here. Thermal currents rising from the desert sands hit the broken plane. Creek grown bang. A loud metallic sound echoes through the ship. What was that? Bragg shouts. The hole got bigger, skipper, the waist gunner yells.

It opened up another inch. The metal is fatiguing. The remaining strands of aluminum are stretching, reaching their yield point. It is a race against time. Bragg wrestles the plane. He uses the engines to steer. He minimizes rudder input. He turns by gently increasing power on one wing and decreasing it on the other, skidding the plane around corners like a boat.

They are approaching the Atlas Mountains. They have to climb to clear the peaks. We can’t climb, Bragg says. If I pull the nose up, the tail weight will snap the spine. He has to thread the needle. He has to fly through the passes, navigating the canyons of the mountains. The navigator Godfrey crawls up to the cockpit. He is pale.

Skipper, if we turn too hard in the pass. I know, Brag says. They enter the valley. The walls of rock rise up on either side. The air is turbulent. The B17 bounces. The tail section wags wildly, describing a two-foot arc. Saralus in the tail is being whipped back and forth. He holds on to his guns, praying. He watches the rivets popping one by one. Ping.

It sounds like a zipper opening slowly. Bragg fights the urge to fight the turbulence. He has to let the plane ridethe bumps. If he stiff arms the controls, the stress will transfer to the brake. He has to be fluid. They clear the final ridge by 50 ft. The base at Biscra is ahead. Prepare for landing. Bragg says this is going to be rough.

He has a choice. He can order the crew to bail out now over the airfield. It would save them if the landing goes wrong. But if they bail out, the shift in weight might snap the tail and Sam Sarpalus is trapped in the back. If Bragg abandons the plane, Sam dies. We’re staying with it. Bragg decides. We land together.

He drops the landing gear. The drag hits the plane. The tail shutters violently. Easy girl, Brag whispers. Hold it together. He lines up on the dirt strip. He can see the ambulances racing out. He can see the ground crews stopping their work, pointing at the sky. From the ground, the all-American looks like a broken toy. It is bent. It is flying crabwise.

It looks like a dragon with its tail cut off. Brag eases the throttles back. The ground rushes up. He has to land on the main wheels and keep the tail wheel off the ground as long as possible. If the tail wheel slams down, the shock will break the fuselage. He flares. The main wheels touch the dirt. Dust billows up. Hold the tail up.

Hold it up. He keeps the yolk forward using the elevator to fly the tail while the wheels roll. The speed bleeds off. 90 m. 80 mph. 70 m. The tail loses lift. It starts to drop. Bragg holds his breath. The tail of the all American settles toward the earth. It doesn’t touch down gently. It drops. Crunch it. The tail wheel hits the dirt.

The fuselage groans. A scream of tearing metal. The rear section sags, dragging in the dust. The brake opens up, but it holds. The bee rolls to a stop. The engines cough and die. The silence of the desert rushes in. For a moment, nobody moves. Then the hatches pop open. The crew tumbles out onto the sand.

They run. They put 50 yards between themselves and the plane, waiting for the fuel tanks to explode or the structure to finally collapse. Sam Sarpalis climbs out of the rear hatch. He steps onto the ground, his knees shaking. He looks at the fuselage he just rode in. He sees daylight. A huge jagged tear separates the tail from the waist.

The only thing connecting the two sections is a single structural beam on the top right. A piece of metal no thicker than a man’s wrist and a few shreds of aluminum skin. The tail section is drooping like a broken finger. An ambulance pulls up. The medic jumps out looking for casualties. He sees 10 men standing in the dust, lighting cigarettes with shaking hands.

“Who’s hurt?” the medic asks. “Nobody,” Bragg says. He stares at his plane. Just her. The base commander arrives in a jeep. He walks around the aircraft. He stops at the brake. He puts his hand through the hole. He shakes his head. “Brag,” the commander says. How the hell did you fly this? I didn’t, brag, says.

I just aimed it. The engineers arrive an hour later. They are Boeing field reps. They measure the break. They take photos. The photos that will become famous. One engineer climbs inside the fuselage. He examines the truss structure. He traces the load paths. It’s the triangle, the engineer explains to brag.

The B17 fuselage is built of triangles. It’s a bridge truss. When the Messor Schmidt cut the bottom lerins, the load transferred to the diagonals. The tension was taken up by the top cord. In English, Bragg asks. It’s built like a tank, Lieutenant. You could cut 40% of the structure away and it will still redistribute the load.

If this was a B-24, the tail would have snapped off instantly. The B-24 relies on the skin for strength. Monaco. The B17 relies on the frame. Bragg looks at the jagged metal. So it wasn’t luck. Oh, it was luck. The engineer says, “If the cut had been 2 in higher, it would have severed the control cables.

You would have nosed in.” The story of the All-American spreads through the airfield. It becomes a shrine. Pilots from other groups come to touch the broken tail. It becomes a symbol of the flying fortress’s legendary durability. But there is a darker reality. The plane is dead. It can never fly again. The structural damage is too severe to repair in the field.

They strip it for parts. They take the engines. They take the guns. They take the radios. As they dismantle the tail, the final piece of metal snaps. The tail section falls to the ground with a heavy thud. It held on just long enough to get them home. Bragg and his crew are given a week of leave. They go to Alers. They drink.

They try to forget the sound of the metal tearing. But Bragg can’t forget the German pilot, the one who saluted. He wonders why the German didn’t shoot. Was it chivalry? Or was it just the calculated decision of a professional who didn’t want to fly through debris? Years later, Bragg would learn the truth about the nightly German pilots.

While some were indeed chivalous, most were pragmatic. The German had likely run outof ammunition or simply judged the B17 to be a dead kill already. Why waste bullets on a corpse? The surprising reason the All-American survived wasn’t enemy mercy. And it wasn’t pilot skill, though Bragg was brilliant.

It was the redundancy of the triangulation. It was the fact that Boeing engineers working with slide rules in the 1930s had overengineered the airframe by a factor of two. They built a plane that could lose its spine and still stand. But the war isn’t over. Bragg gets a new plane. He names it all American II. He goes back to the war. He flies more missions.

He faces more flak. But he never trusts an airplane the same way again. He checks the rivets. He checks the he knows that the line between flying and falling is measured in inches of aluminum. The photograph of the all-American in flight with its tail hanging by a thread becomes one of the most iconic images of World War II.

It is printed in Life magazine. It is plastered on war bond posters. It carries a caption made in America. It becomes a propaganda tool. It tells the public your sons are safe. They are flying in indestructible machines. But Kendrick Bragg knows the truth. The B17 isn’t indestructible. It is just stubborn. Bragg survives the war. He returns to the United States.

He leaves the Air Force and goes into business. He rarely talks about the incident. But the engineering legacy of the All-American lives on. After the war, the Air Force conducts a study on combat damage. They analyze thousands of bombers. They find that the B17 survived catastrophic damage far more often than the B-24 Liberator.

The reason the B24 was more advanced. It had a Davis wing, efficient, fast, long range, but its fuselage was a semi monoke design, relying on the skin for strength. If you punched enough holes in the skin, the tube collapsed. The B17 was old-fashioned. It was heavy. It was draggy, but its internal skeleton, the truss, meant that the skin was just a wrapper.

You could shred the wrapper, but the bones held. This lesson influenced the design of the A10 Warthog 30 years later. The designers of the A10 looked at the B17. They looked at the redundancy. They built a plane with triple spar wings, with titanium bathtubs, with systems that could take a hit and keep flying. The All-American is the grandmother of the warthog.

In 1990, an elderly Kendrick Bragg attends an air show. He sees a B17G sentimental journey taxiing on the ramp. The sound of the radial engines brings it all back. The smell of the oil, the vibration. He walks up to the plane. He runs his hand along the rear fuselage, tracing the line of the rivets. A young pilot sees him.

She’s a beauty, isn’t she, sir. She’s a tank, Bragg corrects him. You flew them? I flew one, Brag says. For a while. He tells the pilot the story. He talks about the truss. He talks about the German pilot. You know, Bragg says, looking at the tale, people say it was a miracle, but miracles are for saints. This was just good welding. The young pilot smiles.

Maybe it was both. Brag nods. He looks up at the sky. It is the same blue as it was over Tunis. He thinks about Sam Sarpales, the tail gunner who sat in that severed tail for 2 hours, watching the world go by through a hole in the floor, trusting that the metal would hold. That is the real story of the all American.

Not the metal, but the trust. the trust the crew placed in the machine and the trust they placed in Bragg to bring them home. The surprising reason wasn’t just the trust. It was the refusal to give up. When the tail was cut, the aerodynamics said crash. The physics said fall. The German pilot said die.

But the all-American said no. And that refusal written in bent aluminum and sheer will is why the aircraft survived 20 enemy hits and one giant collision to become a legend.

News

Germans Captured Him — He Laughed, Then Killed 21 of Them in 45 Seconds

Germans Captured Him — He Laughed, Then Killed 21 of Them in 45 Seconds January 29th, 1945, 2:47 p.m. Holtzheim,…

The US Army Needs Mobility — So They Make A Jeep Assembled In 4 Minutes

The US Army Needs Mobility — So They Make A Jeep Assembled In 4 Minutes 4 minutes. That was…

The US Army Was Losing Tanks on Cobblestone — So a Mechanic Put Wheels on a M18 Hellcat.

The US Army Was Losing Tanks on Cobblestone — So a Mechanic Put Wheels on a M18 Hellcat. Imagine for…

German U-Boat Commanders Were Terrified By The US Navy’s Hunter-Killer Tactics

German U-Boat Commanders Were Terrified By The US Navy’s Hunter-Killer Tactics In early 1943, the fate of the free world…

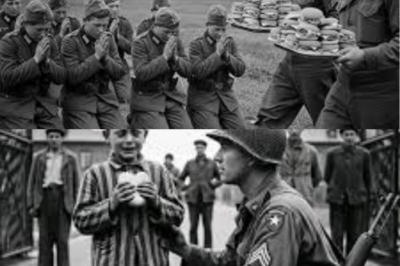

German Child Soldiers Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Hamburgers Instead

German Child Soldiers Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Hamburgers Instead April 22nd, 1945. Camp Carson, Colorado. The gravel…

The US Army Couldn’t Move In Winter — So They Built A Jeep That Could Go On Snow.0[;’

The US Army Couldn’t Move In Winter — So They Built A Jeep That Could Go On Snow. Look closely…

End of content

No more pages to load