The US Army Couldn’t Move In Winter — So They Built A Jeep That Could Go On Snow.

Look closely at the machine emerging from the white mist. At first glance, your brain tells you it is a mistake. It looks like a hallucination born from the freezing delirium of the battlefield. It has the familiar boxy silhouette of a standard issue Willies MB, the workhorse of the American military.

You know the shape. You have seen it in a thousand news reels. But look lower. Look at where the rubber meets the road. There is no road here. There is no rubber at the front. The front wheels are gone. In their place, slicing through the deep powder with impossible grace, are skis. They are not sleek aerodynamic runners designed in a wind tunnel.

They are jagged, heavy plates of scavenged steel hammered into shape by desperate hands and welded crudely to the wheel hubs. They look archaic, like something from a darker, older time, but they are working. While the rest of the world is frozen in place, this strange mechanical centaur is moving. It glides. It drifts.

It floats over the very trap that has swallowed entire armored divisions. This is December 1944. This is the Arden Forest. And this improvised, ugly, magnificent machine is the only thing standing between life and death for thousands of American soldiers. To understand why this Frankenstein vehicle is so important, you have to understand the nightmare that birthed it.

History books call it the Battle of the Bulge. They tell you about the German counteroffensive, the strategic maps, and the movement of armies. But the soldiers on the ground didn’t care about the maps. They cared about the temperature. It was the coldest winter Europe had seen in decades. The thermometer plummeted to zero and stayed there.

The snow didn’t just fall, it buried the world. It piled up three, four feet deep, hiding landmines and erasing roads. The landscape became a white graveyard. And in this deep freeze, American industrial might met its match. The M4 Sherman tank, the pride of Detroit, 30 tons of armor and firepower, became useless. It was too heavy.

Its narrow tracks turned the snow into ice, digging the tank into a pit it couldn’t escape. You could hear the engines screaming, the gears grinding, but the beasts wouldn’t move. They were stranded statues of steel. Trucks jacknifed, ambulances stalled. The supply lines, the arteries of the army were severed. Men were bleeding to death because the vehicles meant to save them couldn’t move 10 ft.

The greatest mechanized army in the world was defeated not by German artillery, but by frozen water. But the American GI has a peculiar relationship with impossible odds. When the manual says stop, the GI starts welding. Somewhere in a freezing maintenance depot, amidst the smell of diesel and despair, a group of field mechanics looked at a standard Jeep and decided to break the rules.

They didn’t wait for orders from the Pentagon. They didn’t wait for a research and development team to design a snowmobile. They looked at the pile of scrap metal in the corner. And they looked at the snow outside. They realized that if the Jeep couldn’t drive through the snow, it had to surf on top of it.

This vehicle you are visualizing is the result of that pure unadulterated desperation. It is a masterpiece of field engineering. The front skis distribute the weight, keeping the nose from diving into the drifts. The rear wheels are modified with heavy chains or sometimes doubled up. Dual tires bolted together to act like a paddle wheel, churning the snow and pushing the rig forward.

It looks ridiculous. It looks unsafe. It looks like a toy made by a madman. But as it tears past a stranded tank column at 30 mph, carrying plasma to a field hospital or ammunition to a cutff platoon, nobody is laughing. The roar of its engine is the sound of defiance. It is the sound of an army refusing to freeze to death.

This is not just a story about a jeep with skis. It is a story about the moment when standard procedure failed and human ingenuity took the wheel. It is the story of how a few rusted modifications turned a quarterton truck into a legend of the snow. This is the anomaly of the Arden. This is the machine that cheated winter.

You assume the greatest threat to the Allied forces in late 1944 was the surprise counterattack by the German army. You picture the Tiger tanks emerging from the mist or the elite SS stormtroopers marching west. But you would be wrong. The most efficient killer in the Arden Forest didn’t carry a Mouser rifle. It didn’t wear a uniform.

It had no rank, no leader, and no mercy. The true enemy was the sky itself. Just as the German offensive began, a meteorological bomb detonated over Europe. It was the White Nightmare. A weather system so ferocious it grounded the Allied air force and turned the battlefield into a deep freeze locker.

For the soldiers on the ground, the war changed instantly. It was no longer a battle for territory. It was a battle for basic biological survival. And in this new war, theUnited States Army realized with terrifying clarity that they had brought the wrong tools to the fight. The pride of the American motorpool was the Willys MB Jeep.

It was nimble, tough, and could go anywhere. Or so they thought. But the engineers back in the States had designed the Jeep for French mud and Italian dust. They had equipped it with narrow militarygrade tires known as NDTs. On hard ground, these tires were fantastic. But in 4 ft of soft, powdery snow, they were fatal. The soldiers called them pizza cutters.

When a standard Jeep hit the deep drifts of the Arden, those narrow tires didn’t float. They sliced. They cut straight down through the snowpack until the vehicle’s frame, the belly of the beast, slammed onto the surface of the snow. This is called high centering. Once that happens, it’s over. The wheels are hanging in the void, spinning uselessly, finding no traction.

The vehicle is effectively dead. Suddenly, the highly mobile American army was paralyzed. The roads, which were barely roads to begin with, vanished. Supply convoys ground to a halt. If you were a soldier on the front line running low on ammunition, you were on your own. If you were freezing, there were no blankets coming.

But the true horror was the medical situation. Field ambulances were just modified trucks, and they suffered the same fate as the jeeps. They bogged down instantly. This created a gruesome reality. A soldier could be wounded just a few miles from a surgical tent. A distance that takes 10 minutes to drive in summer.

But in the white nightmare, that distance became infinity. Men bled to death or died of shock in the back of stalled vehicles while their drivers frantically shoveled snow, screaming in frustration as the wheels just spun deeper. The cold killed faster than shrapnel. Frostbite took toes and fingers before a medic could even bandage a wound.

The forest became a silent trap. The panic started to set in. Not the panic of combat, but the primal panic of being trapped by nature. The commanders were desperate. They needed a vehicle that didn’t exist. They needed something that could skim over the surface like a ghost. Something that defied the physics of ground pressure.

The army didn’t have snowmobiles. They didn’t have helicopters. They had thousands of useless wheels and a ticking clock. It became clear that no rescue was coming from the outside. If these men were going to survive the winter, they couldn’t wait for a miracle from the factories in Detroit. They had to manufacture a miracle right there in the freezing mud.

They had to stop thinking like soldiers and start thinking like mad scientists. The pressure was building. The temperature was dropping. And the breaking point had arrived. Salvation did not come from a clean office in Washington, DC. It did not come from a blueprint drawn by a well-rested engineer with a college degree.

When the solution finally arrived, it came from a frozen tent smelling of gasoline and stale coffee. Born from the minds of men with grease stained knuckles and bloodshot eyes. These were the field mechanics. They were the unsung magicians of the war. The men who could fix a tank engine with a wrench and a prayer. And in the depths of the Arden winter, they realized that the rule book was a suicide pact.

They threw it into the fire to keep warm and started inventing. The logic they settled on was simple, brilliant, and entirely contradictory to military doctrine. If the machine sinks, stop trying to make it drive. Make it float. The transformation began with an act of mechanical violence. The mechanics jacked up the front of the Willys Jeep and ripped the wheels off.

It was a radical move, neutering the vehicle’s ability to steer on pavement. But pavement was a memory. In place of the tires, they didn’t bolt on a factory-made part. They fabricated a solution from the garbage of war. They scavenged steel plating from destroyed trucks. In some units, they reportedly cut the landing gear struts off of wrecked Piper Cub reconnaissance planes.

Using crude arc welders that hissed and popped in the freezing air, they fashioned these scraps into broad, heavy skis. These weren’t the elegant skis of a Swiss resort. They were ugly, heavy slabs of iron bent upwards at the tip like the nose of a tobogen. They welded them directly to the wheel hubs, locking them in place.

The idea was to create a surface area wide enough to disperse the weight of the engine block, allowing the front of the Jeep to plane over the snow rather than plowing into it. But a sled needs a push. With the front wheels gone, the Jeep lost its four-wheel drive capability. All the power was now channeled to the rear axle.

If those back tires spun, the vehicle was dead. The mechanics had to turn the rear wheels into something that could bite into the ice with the ferocity of a tractor. Standard chains weren’t enough. They needed more surface area. So, they improvised a DY system. They took sparetires and welded them directly to the existing rear wheels, creating a double wide footprint.

This prevented the heavy rear end from sinking. But they didn’t stop there. They wrapped these dual wheels in heavyduty truck chains, or in some cases, hand fabricated makeshift tank tracks. They welded steel crossarss between the tire gaps, turning the round wheels into paddle steamers for the snow. It was a brutal modification.

It put immense strain on the axle and the transmission, threatening to snap the drive shaft with every lurch. But the mechanics didn’t care about long-term warranty. They cared about the next 10 miles. What rolled out of those tents was a mechanical mutant. It was a Frankenstein’s monster of parts, a hybrid of a car, a tank, and a sled.

It sat low and wide, looking aggressive and undeniably strange. The welding scars were visible. The steel was unpainted and rusting. It rattled. It clanked. And it looked like it shouldn’t work. But when the driver dropped the clutch and hit the gas, the snow jeep didn’t dig a hole.

The rear claws tore into the hard pack, throwing a rooster tail of ice into the air. The front skis lifted the nose and the machine surged forward. It didn’t fight the winter anymore. It harnessed it. In the middle of the white hell, the Americans had built a chariot. Picture a reconnaissance patrol deep inside the Arden sector.

These are men who have been walking for 6 hours to cover two miles. Their boots are frozen blocks of leather. Their breath hangs in the air like exhaust fumes. They are exhausted, sinking up to their waists with every step, knowing that if they stop moving, they freeze. They pass the abandoned carcasses of standard vehicles, trucks and jeeps buried up to their windshields, monuments to the failure of conventional machinery.

Then they hear it. It isn’t the heavy earthshaking rumble of a Tiger tank. It is a strange schizophrenic sound. From the front, it is a whisper, a soft, rhythmic sh of metal sliding over powder. But from the back, it is a chainsaw growl, a violent churning of chains tearing into the ice. Out of the treeine bursts the snow jeep.

To the enemy, this machine must have looked like a phantom. In a landscape where movement was supposed to be impossible, the snow jeep moved with terrifying purpose. It didn’t plot along. It attacked the terrain. The front skis, those ugly slabs of scavenged iron, acted like the bow of a ship. They didn’t hit the bumps and dips hidden under the snow. They bridged them.

They planed over the surface, carving a clean, silent path through the white. While the front of the vehicle was all grace, the back was pure brutality. Those dual chained wheels kicked up a blizzard of their own, propelling the machine forward with a torque that defied the laws of friction. It was a perfect marriage of silence and violence.

A standard infantry unit would take a full day to flank a German position in this weather. The snow jeep did it in 20 minutes. It drifted around trees, banked off snowbanks, and penetrated areas that the German commanders had marked as impassible on their maps. The Americans were suddenly appearing in places they had no business being, disrupting supply lines and vanishing back into the mist before the enemy could turn their turret guns.

But the true genius of the snow jeep wasn’t found in combat maneuvers. It was found in the back seat where the stakes were much higher. Consider the reality of a wounded soldier in 1944. If you took a bullet in the gut or a piece of shrapnel in the leg, the ride to the field hospital was often what killed you.

A standard truck on a frozen cratered road is a torture chamber. Every bump, every lurch sends a shock wave of pain through a broken body, tearing open sutures and worsening shock. The snow jeep changed the physics of mercy. Because of the front skis, the vehicle didn’t drop into the ruts. It floated over them.

The ride was eerily smooth. Soldiers described it as feeling like a boat on a calm lake. For a man bleeding out on a stretcher strapped to the back, that stability was the difference between life and death. The snow jeep became the ultimate ambulance. It could rush to the front lines, pick up the critical cases that the heavy trucks couldn’t reach, and glide them back to the surgical tents without jolting them to death.

It was a strange sight, this cobbled together open top hot rod, speeding through the trees with a red cross painted on the hood. It was the fastest thing in the forest. It carried the wounded away from the front at speeds that seemed impossible, leaving nothing behind but two long parallel tracks in the snow and the faint smell of exhaust.

In the hands of these drivers, the snow jeep ceased to be a machine. It became a lifeline. It turned the frozen hell of the Arden into a highway. And for the men watching it pass, it was proof that even when the world freezes over, American ingenuity doesn’t stop moving.

The true measure ofa weapon of war is not found in its caliber or its muzzle velocity. It is found in the way it changes the eyes of the men who use it. In the darkest days of the Battle of the Bulge, when hope was being buried under inches of fresh snow every hour, the snow jeep became something more than a mechanical curiosity. To the freezing infantry man huddled in a foxhole, watching his breath turn to ice.

The sight of that strange skiing silhouette cutting through the treeine was a religious experience. It meant you were not forgotten. Zoom in on the driver. He is wrapped in three layers of wool, a scarf over his face, his eyes stinging from the wind. His hands are gripping the steering wheel so hard his knuckles are white.

He is driving a machine that shouldn’t exist, a contraption that vibrates and rattles and defies every safety regulation written by the army. But he loves this machine. He trusts it more than he trusts the generals in the rear. There is a spiritual bond that forms between a soldier and the equipment that keeps him alive. The tank crews love their Shermans.

The pilots love their Mustangs. But the relationship with the snow jeep was different. It was personal. It was intimate. It was a shared secret between the grunt and the mechanic. It was a rebellion against the elements. This vehicle didn’t just carry ammunition. It carried life. When the roads were closed to the heavy trucks, the snow jeep became the only umbilical cord connecting the front line to the rest of the world.

It brought crates of Krations to starving platoon. It brought dry socks to men whose feet were turning black from trenchfoot. It brought the mail, letters from wives and mothers in Ohio and Texas, paper reminders that a warm world still existed somewhere outside this white freezer. And most critically, it brought plasma. There were nights when the temperature dropped so low that morphine ceretses froze solid and had to be thawed in a medic’s armpit.

In those hours, the snow jeep was the angel of mercy. It could transport fresh blood and medical supplies to the very edge of the fighting, places where the silence was usually only broken by the crack of a sniper rifle. When that engine cut off and the driver hopped out with a crate of supplies, the message was clear. It wasn’t just logistics.

It was a statement of defiance. We often look back at World War II and obsess over the super weapons, the atomic bomb, the V2 rocket, the jet fighter. We worship the high-tech marvels. But the Snow Jeep teaches us a different lesson. It proves that the most dangerous weapon the United States military possessed wasn’t made of uranium or advanced circuitry.

It was the American mind. It was the stubborn, hard-headed refusal of a grease monkey mechanic to accept defeat. It was the ability to look at a pile of garbage, a broken airplane, and a frozen jeep and see a solution. The Nazis had superior tanks. They had better optics. But they did not have the flexibility to saw the wheels off a jeep and weld on a pair of skis in the middle of a blizzard.

That ingenuity was the heartbeat of the Allied victory. The snow jeep was the physical embodiment of the American spirit. Ugly, improvised, unpolished, and absolutely unstoppable. Spring arrived in the Arden, not with a fanfare, but with a slow, weeping thaw. By March 1945, the white nightmare began to recede.

The ice that had choked the forests turned into mud. The roads, once buried under 4 ft of powder, revealed themselves again. The great paralysis of the United States Army was over, and the war machine began to roll forward on rubber tires once more. And in the motorpools, the mechanics fired up their cutting torches one last time.

It was a quiet, unceremonious end for the saviors of the winter. The heavy steel skis scavenged from airplanes and scrap heaps were sliced off the wheel hubs. The dual tire chains were unbolted. The crude welds were ground down. The Willys jeeps were returned to their factory specifications, looking small and ordinary again, as if the transformation had never happened.

The skis were thrown onto scrap piles by the side of the road, ugly, rusted, twisted pieces of metal. As the army advanced toward Germany, they left these piles behind. To the untrained eye, they looked like garbage. They looked like the debris of a broken army. But they were the opposite. Those rusting heaps were the physical remnants of a miracle.

There are no grand monuments to the snow jeep. You won’t find one on a pedestal in a town square. Most of them were melted down and turned into girders or soup cans before the war even ended. They were temporary tools for a temporary hell. But for the men who were there, the wounded boy who didn’t bleed to death because a skimmounted ambulance floated him to safety, the rifleman who got his ammunition when the trucks were stuck, those piles of scrap were sacred.

The legacy of the snow jeep isn’t found in a museum exhibit. It is found in theDNA of the American military. It taught a generation of soldiers that the manual is just a suggestion. It proved that when technology fails, human grit takes over. It showed the world that you cannot defeat an army that can build a solution out of thin air, in the dark, with freezing hands.

As the years passed, the stories of the Tiger tanks and the P-51 Mustangs took the spotlight. They were the glamorous heroes of the war. But in the quiet moments of reunion, when the old veterans gathered to talk about the time the world froze over, they spoke of the ugly little car that refused to stop. They remembered the sound of the skis hissing over the ice.

They remembered the silhouette of the centaur coming through the mist. It stands as the ultimate testament to the engineers’s creed. It was ugly. It was dangerous. It was unauthorized. And it was perfect. The war was won by iron and fire, yes, but in the winter of 1944, it was saved by a few guys who looked at a wheel and saw a ski.

They called it a field modification. They called it a desperate hack. But looking back through the lens of time at those faded black and white photographs of a Jeep floating over the white death, we know the truth. History calls it a legend.

News

Germans Captured Him — He Laughed, Then Killed 21 of Them in 45 Seconds

Germans Captured Him — He Laughed, Then Killed 21 of Them in 45 Seconds January 29th, 1945, 2:47 p.m. Holtzheim,…

The US Army Needs Mobility — So They Make A Jeep Assembled In 4 Minutes

The US Army Needs Mobility — So They Make A Jeep Assembled In 4 Minutes 4 minutes. That was…

The US Army Was Losing Tanks on Cobblestone — So a Mechanic Put Wheels on a M18 Hellcat.

The US Army Was Losing Tanks on Cobblestone — So a Mechanic Put Wheels on a M18 Hellcat. Imagine for…

The Surprising Reason This Aircraft Survived 20 Enemy Hits

The Surprising Reason This Aircraft Survived 20 Enemy Hits Tunis, North Africa, February 1, 1943. 26,000 ft. The sky over…

German U-Boat Commanders Were Terrified By The US Navy’s Hunter-Killer Tactics

German U-Boat Commanders Were Terrified By The US Navy’s Hunter-Killer Tactics In early 1943, the fate of the free world…

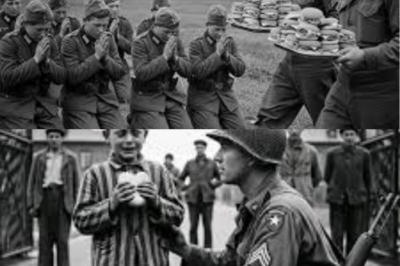

German Child Soldiers Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Hamburgers Instead

German Child Soldiers Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Hamburgers Instead April 22nd, 1945. Camp Carson, Colorado. The gravel…

End of content

No more pages to load