They Laughed at Liberty Ships as ‘Ugly Ducklings’ — Until US Launched 2,700 in 4 Years

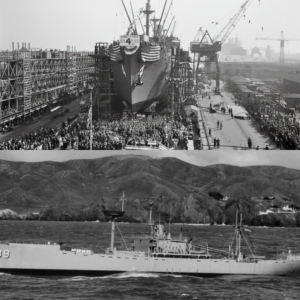

September 17th, 1941. The ways at the Bethlehem Fairfield shipyard in Baltimore, Maryland. The SS Patrick Henry slides into the Papsco River, the first of a new class of emergency cargo vessels that maritime experts are already calling obsolete before she touches water. She is not graceful. She’s not fast.

She’s not impressive by any traditional standard of naval architecture. Her hull is slabsided and utilitarian, resembling a floating shoe box more than a proper ship. Her superructure sits awkwardly amid ships. A boxy five-story island that looks bolted on as an afterthought. Her single steam engine can barely push her to 11 knots, slower than many vessels built in the 19th century.

Traditional shipwrights stand along the waterfront, arms crossed, shaking their heads. One calls her an ugly duckling. The name sticks. The established maritime community dismisses Patrick Henry and her sisters with the casual contempt reserved for emergency solutions that compromise everything that makes a ship worthy of the sea.

These Liberty ships, as President Roosevelt christened them, represent everything that experienced naval architects despise. Mass production over craftsmanship, speed over quality, adequacy over excellence. They are ships built to a price point, designed to be good enough rather than good. Every compromise shows in her lines.

But standing on the platform that September morning watching Patrick Henry settle into the water, Henry Kaiser sees something the experts cannot. He sees possibility. He sees mathematics. He sees the future of industrial warfare. And the future does not care about elegance. The future belongs to the side that can build faster than the enemy can destroy.

If you’re enjoying this deep dive into the story, hit the subscribe button and let us know in the comments from where in the world you are watching from today. The Liberty ship design was born from British desperation and American pragmatism. In 1940, Britain stood alone against Nazi Germany. Her survival dependent entirely on supplies carried across the Atlantic from North America.

Food, fuel, ammunition, aircraft, tanks, everything Britain needed to continue fighting. Had to cross 3,000 mi of ocean. The German submarines controlled with increasing effectiveness. The mathematics were brutal and unforgiving. Britain consumed more tonnage than her shipyards could possibly produce. German hubot were sinking merchant vessels at an accelerating rate.

By the spring of 1941, losses exceeded 600,000 tons per month. At that rate, Britain would starve before Christmas. The British approached American ship builders with an emergency request. Design a simple standardized cargo vessel that could be mass-produced in enormous quantities. Not a good ship, not a fast ship. Not a ship that would serve for decades after the war.

A ship that could be built quickly and cheaply in sufficient numbers to replace losses faster than German torpedoes could sink them. The design parameters were stark. 10,000 dead weight tons of cargo capacity. A single reciprocating steam engine, obsolete but simple to manufacture. Welded construction instead of traditional riveting.

Maximum use of pre-fabricated components. Speed was irrelevant beyond the minimum necessary to keep formation with convoys. Comfort was irrelevant. Longevity was irrelevant. The ships were expected to make perhaps a dozen Atlantic crossings before being sunk or scrapped. The design that emerged was based on a British steamer, a class of vessel so unglamorous that maritime historians barely acknowledged their existence.

steamers were the cargo trucks of the ocean. Slow and homely vessels that carried bulk commodities between minor ports. They had no scheduled routes, no passenger accommodations, no pretensions. They were working ships for working cargo. Functional in the way a hammer is functional. The British designated ocean class refined the steamer concept into something even more austere.

441 ft long, 57 ft wide, a single deck with five cargo holds. Accommodations for 40 crew and up to 70 passengers if necessary. Steam triple expansion engine producing 2500 horsepower. 11 knots maximum speed under ideal conditions. The Gibbs and Cox naval architecture firm in New York adapted the British design for American production methods and renamed it the EC2SC1 type.

The designation told experienced ship rights everything they needed to know and everything they disdained. E for emergency, C for cargo, two for a ship between 400 and 450 ft long, S for steam, C1 for the specific design iteration. Even the designation announced that these were temporary expedience, not real ships.

Traditional ship builders examined the Liberty ship plans with unconcealed contempt. The design violated virtually every principle of elegant naval architecture. The hull form was so simple it could have been drawn with a straight edge. The sheer line, that graceful curve from bow to stern that defined a beautiful ship, wasnearly flat.

The bow was blunt and squared, designed for ease of construction rather than hydrodnamic efficiency. The stern was equally ungraceful, chopped off abruptly to accommodate a massive single rudder. The superructure broke the cardinal rule of ship design by sitting amid ships where it disrupted the flow of cargo loading. Proper vessels placed the bridge and accommodations aft, leaving the working deck clear.

Liberty ships looked unfinished, as though the designer had sketched the basic concept and forgotten to refine the details. The performance specifications confirmed what the appearance suggested. 11 knots, maximum speed, made Liberty ships barely faster than sailing vessels from a century earlier. Modern freighters could sustain 16 to 18 knots.

Fast cargo liners exceeded 20 knots. 11 knots meant that Liberty ships would struggle to maintain convoy formation in heavy seas. They would be targets, slow and wallowing, unable to maneuver or escape. When Ubot attacked, their single propeller made them vulnerable. One torpedo to the stern would leave them dead in the water.

Their single engine eliminated redundancy. Any mechanical failure meant drifting helplessly until repairs could be completed or a tug arrived. The construction method was equally controversial. Traditional ships were riveted, steel plates overlapped at the seams and were joined by thousands of heated rivets hammered into place by skilled teams.

The process was labor intensive and time-conuming, but it had built every great navy in maritime history. Riveting created natural fracture barriers. If a plate cracked, the damage stopped at the seam between sections. Riveted ships could survive damage that would be catastrophic in other construction methods. Liberty ships were welded.

Electric arc welding fused the steel plates directly, creating continuous seams without overlapping metal. Welding was faster and required less material, but it created potential failure points that made experienced shipwrites. Nervous continuous welded seams meant that cracks could propagate unimpeded from one end of the vessel to the other.

The steel used in ship construction had been developed for riveted assembly. Nobody knew for certain how welded construction would perform under the stresses of North Atlantic storms and battle damage. The aesthetic objections ran deeper than mere appearance or construction technique.

Liberty ships represented the industrialization of what had been a craft for millennia. Traditional ship builders were artisans who learned their trade through years of apprenticeship. They could look at a hull taking shape and know instinctively whether the lines were fair, whether the vessel would ride well in heavy seas.

They took pride in building ships that would serve for decades, vessels that embodied the accumulated wisdom of generations. Each ship was slightly unique, incorporating the judgment and skill of the men who built it. Liberty ships eliminated craftsmanship from the equation. They were designed to be assembled by semi-skilled workers following standardized procedures.

The pre-fabrication approach meant that components arrived at the shipyard already complete, manufactured in factories across the country by workers who had never seen the ocean. Bow sections from Pennsylvania, engine mounts from Michigan, superructure assemblies from Washington. The shipyard workers were assemblers, not shipwrites.

They welded sections together according to numbered diagrams like building enormous steel models from instruction sheets. The maritime establishment watched the first Liberty ships take shape with the grim satisfaction of experts witnessing a predictable disaster. These ugly ducklings would vindicate traditional methods.

They would prove that you could not mass-produce ships like automobiles. The sea would expose every shortcut and compromise. Liberty ships would crack in heavy weather. Their welded seams would fail. Their obsolete engines would break down. They would wallow in rough seas, be impossible to handle in port, and prove unseaorthy in every condition that mattered.

Men would die because bureaucrats and industrialists had ignored the warnings of professionals who actually understood the sea. What the experts failed to recognize was that adequacy was exactly what America needed. Liberty ships did not need to be excellent. They needed to be sufficient in overwhelming numbers. They needed to carry cargo from American ports to British docks faster than German submarines could sink them.

Everything else was a relevant luxury that would cost time America did not have. The Patrick Henry completed her sea trials in October 1941 and departed on her first voyage in December carrying 10,000 tons of military supplies to Britain. She crossed the Atlantic without incident. Though her crew reported that she rolled heavily in moderate seas, and her slow speed made station keeping difficult, traditional shipwrites noddedknowingly, the problems would multiply.

Give the ugly duckling time, and her flaws would become catastrophic. Then the United States entered the war. December 7th, 1941. Pearl Harbor. Suddenly, America faced a two ocean conflict, requiring millions of tons of supplies shipped thousands of miles to theaters in Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific.

The Navy needed tankers to fuel the fleet. The Army needed transports to move troops. The Air Force needed cargo vessels to ship disassembled bombers. Britain needed food and ammunition. The Soviet Union, barely surviving the German invasion, desperately needed American supplies delivered via Arctic convoys to Mman. The mathematics were staggering.

Military planners estimated that America would need to transport 50 million tons of cargo annually just to sustain existing operations before accounting for the massive buildup necessary to eventually invade occupied Europe. Traditional shipyards, even working at maximum capacity, could not possibly meet that demand.

They were already overwhelmed with naval contracts for destroyers, cruisers, and aircraft carriers. Merchant ship construction using conventional methods would take years to scale up sufficiently. Henry Kaiser and his competitors in the emergency ship building program saw opportunity where traditional builders saw impossible demands.

If Liberty ships could be mass- prodduced using assembly line techniques, then quantity could overwhelm every objection about quality. The ships did not need to be fast or graceful. They needed to exist in such enormous numbers that losing individual vessels became acceptable attrition rather than strategic disaster. The production acceleration that followed was unprecedented in maritime history.

Kaiser’s Richmond shipyards in California, Bethlehem Fairfield in Baltimore, New England, Ship Building in Maine, Oregon Ship Building in Portland, Todd Houston Ship Building in Texas. By mid 1942, 18 shipyards across the United States were building Liberty ships using mass production techniques that would have been impossible to implement with traditional construction methods.

The pre-fabrication approach meant that dozens of ships could be under construction simultaneously. While one vessel was being assembled in the ways, hundreds of workers in separate facilities were welding the components for the next 10 vessels. Bow sections, stern assemblies, deck houses, bulkheads, all manufactured to identical specifications that guaranteed interchangeability.

The construction times plummeted. The first Liberty ships required 230 days from Keel laying to launch. By early 1942, average construction time had dropped to 140 days. 6 months later, the average fell to 70 days. By late 1942, Kaiser’s Richmond yards were averaging 42 days from ke to launch. Less than 6 weeks to build a complete oceangoing cargo vessel.

The ugly ducklings were rolling off assembly lines faster than automobile manufacturers produced cars. The record that captured global attention came in November 1942. The SS Robert E. Piri built in 4 days, 15 hours, and 29 minutes. The achievement seemed to violate physical laws. A 10,000 ton ship containing 250,000 individual components assembled in less than 5 days.

News reels showed the time-lapse footage. The keel laid prefabricated sections swung into place by massive cranes. Welders swarming over the hull in roundthe-clock shifts. The completed vessel sliding into San Francisco Bay while traditional shipyards were still ordering steel for vessels whose kees would not be laid for months. The Robert E.

Piri was a publicity stunt, a proof of concept that required extraordinary coordination and preparation, but she was also a fully functional ship that made six wartime voyages. More importantly, she demonstrated that the average construction time of 42 days was not an optimistic target. It was an achievable standard that could be maintained across multiple shipyards simultaneously.

By 1943, American shipyards were launching three Liberty ships daily. Three complete cargo vessels every single day, 90 ships per month, more than 1,000 ships per year. The ugly ducklings were multiplying faster than anyone had thought possible. If you find this story engaging, please take a moment to subscribe and enable notifications.

It helps us continue producing in-depth content like this. The German Naval Command watched the production figures with growing alarm that turned to horror as the implications became clear. Capitanzi Ernst Hoffman coordinating Yubot operations from headquarters in Lauron France received the intelligence reports and understood immediately that Germany had already lost the battle of the Atlantic.

The mathematics were irrefutable. A yubot on a successful patrol might sink four or five merchant vessels before returning to port for resupply. The return to port required weeks rearming, refueling, restocking provisions and allowing the crew to recover from the psychologicalstrain of combat operations meant that each submarine spent more time in port than at sea.

Germany had roughly 400 operational Yubot at peak deployment, even under impossibly optimistic assumptions the Yubot fleet could sink perhaps 2,000 Allied vessels per year. America was building 1,200 Liberty ships annually, plus hundreds of other cargo vessels, tankers, and transports. Britain continued building ships. Canada built ships.

The disparity was overwhelming. Germany would need to sink more merchant vessels than the Allies could construct just to maintain the strategic balance. Instead, Allied construction exceeded Yubot sinking rates by a factor of 3 to one. The gap widened monthly as American production accelerated while Yubot losses increased.

Hoffman drafted careful reports to Admiral Carl Donitz, commander of the Yubot fleet. Current strategy unsustainable. Enemy production capacity exceeds destruction capacity by factor of 3 to one. This disparity is increasing monthly. Recommend strategic reassessment of Atlantic operations. The reports were forwarded through channels to Berlin where they were read and filed and changed nothing.

Germany’s strategic situation offered no alternatives. The Yubot fleet was the only weapon that could strike at Allied logistics and to abandon the Atlantic campaign was to concede defeat to allow unlimited supply shipments that would enable the eventual invasion of occupied Europe. So the Yubot continued hunting convoys in the North Atlantic, sinking individual vessels in tactical victories that added up to strategic irrelevance for every Liberty ship sent to the bottom.

Three more launched from American shipyards. The ugly ducklings were winning through simple mathematics. They did not need to outfight German submarines. They only needed to exist in such overwhelming numbers that losses became acceptable attrition. The critics who had dismissed Liberty ships as death traps were forced to confront uncomfortable evidence.

The ugly ducklings were crossing the Atlantic successfully. They were delivering cargo to Britain, to the Soviet Union, to North Africa and the Mediterranean. They were surviving yubot attacks, surviving storms, surviving conditions that maritime experts had predicted would expose every compromised feature of their design.

They were not graceful. They were not fast. They were not impressive, but they were sufficient. And sufficiency in overwhelming quantities was winning the EO war. The proof arrived not in design studies or expert analysis, but in operational reality across the most hostile waters on Earth. Liberty ships were deployed to every theater of the war, subjected to conditions that would have destroyed vessels built with more care and less urgency.

The North Atlantic in winter, where waves towered 40 ft high and temperatures plunged below freezing. The Mansk run to the Soviet Union through Arctic waters patrolled by German aircraft, submarines, and surface raiders. The Mediterranean, where Luftvafa bombers turn supply convoys into shooting galleries. The Pacific, where distances exceeded anything in the Atlantic and tropical conditions, tested equipment in different ways.

The Ugly Ducklings survived. More than survived, they performed. The SS Steven Hopkins provided the most dramatic vindication of Liberty ship resilience. September 27th, 1942, South Atlantic Ocean. The Hopkins, carrying war supplies to the Middle East, encountered the German armed merchant raider Steer and her escort, the tanker Tannenfels.

The Germans opened fire first. Their heavier guns and trained crews, giving them overwhelming tactical advantage. A proper warship would have fled. The Hopkins had a single 4-in gun mounted aft, manned by a Navy armed guard detachment whose primary duty was shooting at aircraft against a purpose-built radar with 6-in guns.

The Hopkins should have been destroyed in minutes. The crew of the Hopkins fought back. The 4-in gun crew remained at their station despite direct hits that killed several men. They fired at the Sty with desperate accuracy, scoring hits on the Raiders’s bridge and water line. The battle lasted 20 minutes, both vessels exchanging fire at point blank range.

The Hopkins absorbed enormous punishment. Shells penetrated her hull. Fires broke out in the cargo holds. Her steering was damaged. The captain was mortally wounded. But the ugly duckling refused to sink quickly enough for the Germans to escape undamaged. The final shells from the Hopkins struck the sty below the water line.

The raider began taking on water faster than her pumps could manage. Both vessels were dying, but the Hopkins had done the impossible. She had mortally wounded a purpose-built warship with a single defensive gun. The Hopkins sank first, her crew abandoning ship into lifeboats. The sty followed her to the bottom 4 hours later.

The only German surface raider destroyed by a merchant vessel during the entire war. The Hopkins was an uglyduckling built in 8 weeks by semi-skilled workers using emergency construction methods. She should have been a helpless victim. Instead, she fought a battle that would have done credit to a destroyer, and she won. The Navy awarded her captain the Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medalostuously.

The armed guard crew received commendations. The ship herself received a kind of immortality in merchant marine history, proof that Liberty ships and their crews could do far more than the experts predicted. The statistical reality of Liberty ship performance contradicted every prediction made by traditional ship builders.

Of the 2,710 Liberty ships constructed during the war, 200 were lost to enemy action. Less than 8% combat losses. That survival rate exceeded most naval vessel classes. Destroyers, purpose-built warships designed for combat, suffered higher percentage losses. Liberty ships designed as disposable cargo carriers expected to last perhaps a year proved remarkably difficult to sink.

German torpedoes struck Liberty ships and failed to achieve catastrophic damage. The ship’s simple construction meant that there were fewer complex systems to fail. The multiple cargo holds were separated by watertight bulkheads that contained flooding. The obsolete triple expansion steam engines, dismissed as antiques by modern naval architects, proved incredibly reliable and easy to repair with basic tools.

The SS Richard Montgomery survived a torpedo hit that blew a 40ft hole in her side. Her crew managed to contain the flooding and limp into port for repairs. She was back in service 6 weeks later, carrying another load of supplies to Europe. The SS Nathaniel Green took a German bomb directly through her number three cargo hold.

The bomb exited through the bottom of the hull without exploding, leaving a neat hole that the crew patched with concrete and timber. The Green completed her voyage and delivered her cargo on schedule. These were not isolated incidents. They were typical examples of Liberty ship resilience that accumulated into undeniable evidence. The construction flaws that critics predicted would cause catastrophic failures did occasionally occur, but not in the apocalyptic numbers anticipated.

Some Liberty ships developed cracks in their welded holes, particularly during the brutal winter of 1943 and 44, when North Atlantic temperatures dropped below freezing. A handful broke apart completely, their holes fracturing in ways that riveted construction might have contained. The SS Skenctities split in half while docked in calm water, her hull cracking completely around the midsection.

The SSSO Manhattan broke in two during a storm. These failures prompted emergency investigations into welded ship construction and resulted in design modifications that strengthened critical stress points. But the overwhelming majority of Liberty ships never experienced structural failures. They crossed the Atlantic hundreds of times.

They weathered storms that would have tested any vessel. They absorbed battle damage and continued operating. The welded construction that traditionalists had warned would prove catastrophic actually performed remarkably well. The continuous welded seams distributed stress more evenly than riveted joints. The flexibility of welded holes allowed them to work in heavy seas without the rigid fracturing that could occur in riveted vessels.

Once steel chemistry was corrected and quality control improved, welded Liberty ships proved as durable as any traditionally constructed vessel. The ugly ducklings demonstrated their worth through sheer persistence. They were present at every major Allied operation from 1942 onward. Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa.

Liberty ships carried the assault troops and their supplies. the Sicily invasion. Liberty ships formed the bulk of the invasion fleet cargo capacity. The Normandy landings on June 6th, 1944. 130 Liberty ships participated in Operation Overlord, carrying tanks, ammunition, fuel, and supplies that sustained the Allied armies after they broke out from the beaches.

Some were deliberately scuttled as breakwaters to create artificial harbors. Others made repeated channel crossings, shuttling supplies from Britain to the expanding beach head. The ugly ducklings that critics said would never survive combat operations were instrumental in the largest amphibious invasion in military history.

In the Pacific theater, Liberty ships faced different challenges across vast distances that dwarfed Atlantic crossings. The voyage from San Francisco to Brisbane, Australia, covered 7,000 mi of open ocean. Supply lines stretched from the American West Coast to forward bases in the Philippines, Okinawa, and eventually Japan itself.

Liberty ships carried the fuel, ammunition, and supplies that enabled the island hopping campaign across the central Pacific. They delivered food to isolated garrisons. They transported aviation fuel to airfields carved from thejungle. They moved entire armies between islands separated by thousands of miles of hostile ocean.

The slow, ugly cargo vessels that were supposed to be inadequate for modern warfare proved indispensable to victory in the world’s largest ocean. The human stories aboard Liberty ships contradicted another set of expert predictions. Traditional merchant mariners had claimed that the ships would be impossible to operate safely with the inexperienced crews, that wartime necessity required.

Proper seammanship took years to learn. Navigating by celestial observation demanded mathematical skill and practice. Operating steam plants required engineering knowledge that could not be taught quickly. The experts predicted chaos, collisions, mechanical breakdowns, and unnecessary losses caused by incompetent crews.

The reality proved far different. Young men with minimal training learned to navigate across oceans. Engineers who had never seen a steam turbine before the war kept obsolete triple expansion engines running through mechanical ingenuity and determination. Armed guard crews, sailors who had been civilians months earlier, manned defensive guns with increasing effectiveness.

The SS Booker T. Washington was crewed almost entirely by African-American merchant mariners. A deliberate decision by the war shipping administration to demonstrate that black sailors could perform as capably as white crews. Washington’s performance over 18 months of combat operations vindicated that decision comprehensively.

She made repeated Atlantic crossings without incident. Her crew maintained the ship to exemplary standards. Her armed guard detachment shot down two German aircraft. The Washington survived the war and her crew earned commendations that helped break down racial barriers in the merchant marine.

The ugly duckling crewed by men whom traditional shipping companies had refused to hire proved that competence had nothing to do with race and everything to do with opportunity and training. Women served aboard Liberty ships in roles that would have been inconceivable before the war, not as crew at sea, but as the workers who built the ships with unprecedented speed.

Wendy the welder became a cultural icon, representing thousands of women who learned industrial trades in weeks and performed them with skill that matched any man. The Richmond shipyards employed over 30,000 women at peak production. They operated cranes, welded holes, installed machinery, performed quality inspections.

The ugly ducklings were built by people whom traditional shipyards had dismissed as unsuitable for skilled work. The ship’s success was inseparable from the success of workers who proved that expertise could be developed quickly when necessity demanded it, and training was provided systematically. By 1944, the strategic situation in the Atlantic had shifted decisively in favor of the Allies.

Not because of superior anti-ubmarine tactics alone, but because Liberty ship production had rendered the Yubot threat strategically irrelevant. German submarines were still dangerous. They still sank individual vessels, but they could not sink ships faster than American shipyards built them. Uh the production curve crossed the loss curve in mid 1943 and never reversed.

By the end of 1944, Allied merchant shipping tonnage exceeded pre-war levels despite four years of continuous losses. The mathematics that German naval planners had feared in 1942 had become undeniable reality. Admiral Carl Donitz, commander of the Yubot fleet, understood the implications with bitter clarity.

In his post-war memoir, he wrote with remarkable cander about the moment he realized the Battle of the Atlantic was lost. It was not any single tactical defeat. It was the intelligence reports showing American ship production figures. The numbers made continued yubot operations pointless. Germany was fighting industrial capacity with operational skill.

And that was a battle no amount of tactical brilliance could win. The ugly ducklings had defeated the most sophisticated submarine force in the world through the simple expedient of existing in overwhelming numbers. The final production statistics told the complete story. Between 1941 and 1945, American shipyards delivered 2,710 Liberty ships.

Total construction time for all vessels combined exceeded 17 million man-hour. The entire program cost 13 billion in 1940s currency, roughly 200 billion in modern terms as it was the largest emergency industrial program in American history. To that point, surpassed only by the Manhattan project in technological ambition and the overall war production effort in total scale.

The Liberty ship program represented emergency industrial mobilization functioning exactly as designed. Adequate ships built in overwhelming quantity by workers trained quickly and deployed rapidly to where they were needed most. The average Liberty ship cost just under $2 million to build and took 42 days from ke layingto launch.

A traditional cargo vessel of comparable size cost twice as much and required 6 months to construct. The ugly ducklings delivered twice the capacity at half the cost in one-third the time. That efficiency translated directly into strategic advantage. Every dollar saved on ship construction, funded bombers, tanks, ammunition.

Every day saved in construction meant supplies reached front lines sooner. The economic mathematics of Liberty ships were as decisive as their operational performance. The postwar fate of Liberty ships vindicated their design in ways that critics could never have anticipated. These disposable vessels built to last perhaps 5 years and expected to be scrapped after the war proved remarkably durable.

Many operated commercially for decades. The SS John W. Brown and SS Jeremiah O’Brien were maintained as operational museum ships into the 21st century, more than 75 years after their construction. Both vessels could still cross oceans under their own power. The Ugly Ducklings outlasted most of their critics, and many of the traditional ships that were supposed to be superior.

Several Liberty ships were converted for specialized postwar uses that demonstrated their fundamental soundness of design. The SS Grand Camp loaded with ammonium nitrate fertilizer exploded in Texas City, Texas in 1947, causing one of the worst industrial disasters in American history. But that catastrophe resulted from cargo mishandling, not ship design flaws.

Other Liberty ships became training vessels, floating power plants, storage hulks, even floating hotels. Their simple construction made them adaptable to purposes never imagined during their hasty wartime design process. The ships built as emergency expedience proved versatile enough for peaceime applications that required reliability and capacity more than speed or elegance.

The international legacy of Liberty ships transformed global ship building practices in ways that continued long after the last vessel was scrapped. The mass production techniques pioneered in American wartime shipyards became standard practice worldwide. Japanese ship builders studied Liberty ship construction methods and incorporated pre-fabrication and welded assembly into their post-war reconstruction.

By the 1960s, Japan had become the world’s largest ship building nation using techniques refined from American wartime innovations. South Korean shipyards followed similar development paths, learning from both American and Japanese examples. The ugly ducklings, built in desperate haste during wartime, became the foundation for post-war maritime industries that eventually surpassed American production capacity.

The welding techniques perfected under wartime pressure revolutionized not just ship building, but all large-scale steel construction. The lessons learned from Liberty ship structural failures led directly to the development of fracture mechanics as a formal engineering discipline. Modern understanding of how cracks propagate through metals, how stress concentrations develop at design discontinuities, how temperature affects material properties, all trace their origins to the intensive research prompted by Liberty ship failures during

the war. The Ugly Ducklings taught engineers lessons that influenced everything from bridge construction to aircraft design to pressure vessel manufacturing. Henry Kaiser emerged from the war as an industrial titan whose reputation transcended ship building. His methods had proved that unconventional thinking could revolutionize established industries.

That outsiders unencumbered by tradition could achieve what experts considered impossible. that adequate solutions produced in overwhelming quantities could defeat superior quality in limited numbers. Kaiser applied those principles to postwar ventures that included automobile manufacturing, steel production, and healthcare.

Kaiser Permanente, born from the medical services provided to shipyard workers, became one of America’s largest healthare organizations, serving millions of patients using the same systematic approach that had built ships faster than experts thought possible. The ugly duckling metaphor that began as an insult became a badge of honor in maritime history.

Liberty ships were never beautiful. They never achieved the grace or elegance that defined classic ocean liners or naval vessels, but they accomplished something far more important than aesthetic appeal. They won a war through sheer industrial persistence. They proved that in total warfare, production capacity matters as much as tactical brilliance.

That quantity can become quality when deployed systematically. that humble, unglamorous solutions can achieve strategic victories that more sophisticated approaches cannot match. The final irony of Liberty ship history emerged in the post-war period when maritime historians and naval architects reassessed the emergency ship building program with the clarity that peaceimeperspective enabled.

The ugly ducklings had not merely succeeded despite their compromises. They had succeeded in part because of those compromises. The simple construction made them easy to repair with basic tools in forward ports. The obsolete engines were reliable and familiar to engineers worldwide. The plane holes were adaptable to modifications that more refined designs could not accommodate.

The features that traditional ship builders had mocked as primitive actually contributed to operational effectiveness in ways that sophisticated designs could not match. The workers who built Liberty ships returned to civilian life carrying skills and confidence that transformed American industry. Women who had welded ships, built careers in manufacturing and construction.

African-Americans who had demonstrated their capabilities in shipyards demanded and sometimes received opportunities in other industries. Veterans who had kept obsolete engines running across oceans became peacetime engineers and mechanics. The social changes initiated in shipyards during wartime necessity continued into post-war decades, contributing to the gradual dismantling of discriminatory practices that had limited human potential.

The Ugly Ducklings helped build not just a military victory, but a more equitable society. The Liberty Ship program demonstrated that American industrial capacity, properly mobilized and intelligently directed, could overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges. That combination of resources, ingenuity, and determination changed the course of history.

The same principles that built ships faster than enemies could sink them would later put humans on the moon, create the interstate highway system, develop commercial jet aviation. The confidence born in wartime shipyards persisted through peaceime challenges. America had proved it could accomplish anything when necessity demanded it.

The ugly ducklings were floating proof that the impossible was merely difficult, and that difficult was just a matter of proper organization and sufficient will. Standing on the dock in Baltimore, Maryland today, you can watch the SS John W. Brown depart on her occasional demonstration cruises, the ship moves slowly, pushed by her obsolete triple expansion engine at a stately 11 knots.

She’s not impressive by modern standards. Container ships dwarf her. Modern cargo vessels can sustain speeds twice as fast. But the Brown is still afloat 75 years after her construction. She still crosses the Chesapeake Bay under her own power. The ugly duckling that experts said would never survive wartime service has outlasted most of the shipyards that built her.

And all of the critics who dismissed her design, the mathematics that won the war, remain as clear today as they were in 1943. 2,710 Liberty ships, 200 lost to enemy action. 2,510 that survived to deliver their cargo, support their crews, and accomplish their missions. The ugly ducklings built by semi-skilled workers in a weeks using emergency construction methods achieved a survival rate that rivaled purpose-built warships.

They proved that adequacy in overwhelming numbers defeats superiority in limited quantity. They demonstrated that industrial capacity properly directed becomes military power that no amount of tactical brilliance can overcome. The legacy of liberty ships extends far beyond maritime history into the fundamental understanding of how industrial democracies wage total war.

Victory belongs not just to the side with better weapons or braver soldiers, but to the side that can produce faster, adapt more quickly, mobilize more completely. The ugly ducklings won because America could build them faster than Germany could sink them. That simple mathematical reality decided the Battle of the Atlantic more decisively than any convoy battle or anti-ubmarine tactic.

The ships that were supposed to be inadequate proved adequate enough to win the war, and adequacy in overwhelming quantity was exactly what victory required. They laughed at Liberty ships as ugly ducklings. They mocked the simplified design, the obsolete engines, the untrained workers, the welded construction.

They [clears throat] predicted catastrophic failures, unnecessary casualties, strategic disaster. They were wrong about everything that mattered. The ugly ducklings crossed every ocean, supplied every theater, survived every test. They proved that sometimes the most important innovation is not building something better but building enough.

That emergency solutions can become permanent successes. That unconventional thinking defeats conventional wisdom when circumstances demand impossible performance. And that the ugliest duckling can achieve what beautiful swans never accomplish. winning a war through sheer relentless overwhelming persistence. Thank you for watching.

For more detailed historical breakdowns, check out the other videos on your screen now. And don’t forget to subscribe.

News

Donte DiVincenzo Delivers Perfect Message on Wolves’ Mindset After Hot Start

Donte DiVincenzo Delivers Perfect Message on Wolves’ Mindset After Hot Start January 9, 2026, 12:06pm EST • By Ayushi Bhardwaj Donte DiVincenzo…

The Army Tried to Kick Him Out 8 Times — This “Reject” Stopped 700 Germans

The Army Tried to Kick Him Out 8 Times — This “Reject” Stopped 700 Germans The US army tried to…

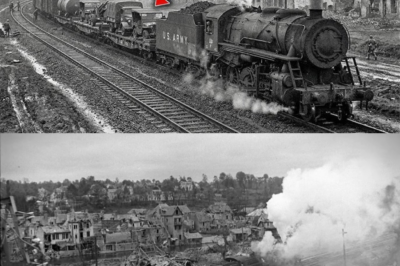

The Day America’s Crudest Locomotive Proved It Could Carry An Army Into Germany

The Day America’s Crudest Locomotive Proved It Could Carry An Army Into Germany September 3rd, 1944. Eboo Junction, South Wales….

John Wayne received the letter from his teacher and did something that no Hollywood star would do today

John Wayne Received This Teacher’s Letter And Did Something No Hollowood Star Would Do Today March 1961, a school teacher…

‘Please Stop—I’m Infected’ German Female POWs Didn’t Expect This From U.S. Soldiers

‘Please Stop—I’m Infected’ German Female POWs Didn’t Expect This From U.S. Soldiers 1944, Western Germany. As Allied forces pushed east…

Germans Were Shocked When One American Soldier Held Off 250 Germans For Over An Hour Alone

Germans Were Shocked When One American Soldier Held Off 250 Germans For Over An Hour Alone January 26th, 1945. 2:20…

End of content

No more pages to load