What Eisenhower Said When Montgomery Insisted Patton Be Removed After His 36-Hour Rhine Crossing

March 1945, Western Germany. Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery had spent months meticulously preparing Operation Plunder, envisioning it as the most spectacular river crossing operation since the D-Day landings themselves. This was to be a massive, elaborately orchestrated assault across the Ry River that would conclusively demonstrate British military excellence and finally erase the painful memory of Market Gardens’s catastrophic failure six months earlier at Arnum.

The sheer scope and ambition of Operation Plunder was absolutely staggering in its scale. Over 80,000 British and Canadian troops would participate in the coordinated assault. 5,000 artillery pieces had been carefully positioned along the western bank of the Rine, ready to deliver a crushing preparatory bombardment that would pulverize German defensive positions.

Pontoon bridges had been pre-fabricated in workshops far behind the lines and staged at forward positions for rapid deployment the moment conditions allowed. Airborne troops would drop behind German lines to secure key terrain features and prevent reinforcements from reaching the crossing sites where the assault would occur.

Montgomery had calculated every conceivable detail with obsessive precision. Supply depots had been established with exact inventories meticulously tracked. ammunition, fuel, food, medical supplies, every item cataloged and positioned. Engineers had mapped the river bottom at multiple potential crossing points using depth soundings, determining optimal locations for bridge placement based on current speed, riverbed composition, and approach routes.

Intelligence officers had analyzed German defensive positions through aerial reconnaissance and agent reports, creating detailed maps showing machine gun nests, artillery batteries, observation posts, and troop concentrations. The operation’s timeline was fixed with the precision of a Swiss watch, every moment planned. The artillery bombardment would commence at exactly 2100 hours on March 23rd.

Infantry assault boats would launch precisely at 2130 hours. The first wave would establish secure beach heads on the eastern bank. Engineers would begin bridge construction at 2200 hours. By dawn on March 24th, armor would be crossing into Germany and strength. It was military planning at its absolute finest.

The kind of methodical, comprehensive approach that Montgomery believed represented proper military professionalism and British military tradition. This was how wars should be fought. with careful preparation, overwhelming force applied at decisive points, and minimal acceptable risk. Montgomery had even invited Prime Minister Winston Churchill to attend personally and witnessed the operation firsthand.

Churchill had accepted the invitation enthusiastically, eager to see British forces deliver what Montgomery promised would be the decisive blow. Montgomery assured him the operation would be the crowning moment of the European War, the decisive blow that would shatter German defenses and open the path toward Berlin itself.

For Montgomery, Operation Plunder represented far more than just a river crossing operation. It was vindication, redemption, proof. After Market Garden’s failure in September 1944, when his ambitious plan to seize bridges across the Rine had ended in absolute disaster at Arnham, with the British First Airborne Division virtually destroyed, Montgomery desperately needed a clear, unambiguous success.

Operation Plunder would provide that success definitively. It would demonstrate beyond question that British forces, properly led and properly supplied with adequate resources, were the equal of any army in the world. Montgomery’s confidence was absolute and unshakable. He had the men, experienced, well-trained troops. He had the equipment, everything needed for a major operation.

He had the plan perfected through months of careful study. Nothing could possibly go wrong because he had systematically eliminated every conceivable variable through meticulous preparation. But approximately 200 kilometers to the south, another general was looking at the same river with very different ideas about how to cross it.

Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr. commanding the US Third Army with his characteristic aggressive flare, had received orders from General Omar Bradley regarding the Rine crossing. Third Army was to advance to the area around Mines, approximately 160 km south of Montgomery’s planned crossing site. When Patton reached the Rine at Mines, he was authorized to cross if a favorable opportunity presented itself.

The orders were clear, but notably not urgent. Eisenhower’s overall strategic plan prioritized Montgomery’s northern crossing as the main effort. Resources, fuel, ammunition, bridging equipment, air support were being concentrated to support Operation Plunder. Third Army’s crossing at mines was explicitly secondary, something to be executed after Montgomery’s operation succeededand drew German reserves northward.

Patton understood the strategic logic behind this allocation perfectly well. He also hated it with visceral intensity. For Patton, the Rine represented the last major geographic obstacle before driving into the very heart of Germany. Crossing it quickly meant ending the war faster, saving Allied lives.

Crossing it before Montgomery meant demonstrating that American audacity and speed were tactically superior to British caution and elaborate preparation. Patton had multiple powerful motivations driving him. He wanted glory for American arms to demonstrate conclusively that US forces were the dominant Allied power. He wanted recognition for Third Army, the formation he commanded and had led across France and deep into Germany.

And yes, he wanted personal glory, the satisfaction of achieving a spectacular success that would be remembered in military history long after he was gone. But above all else, Patton wanted to beat Montgomery to the rine. The rivalry between them was deep, personal, and rooted in years of friction. They had clashed repeatedly in Sicily, throughout France, across the entire European campaign.

Montgomery represented everything Patton genuinely despised about military leadership. Caution when aggression was called for, rigid planning when flexibility was needed, an obsession with elaborate setpiece battles rather than exploitation and relentless pursuit. And Montgomery’s attitude toward American forces absolutely infuriated Patton at every level.

Montgomery frequently implied, sometimes subtly, sometimes not, that British forces were more professional, better disciplined, more militarily sound, and competent than their American counterparts. That American successes were due primarily to overwhelming resources and industrial capacity rather than actual tactical skill. that generals like Patton were cowboys, brave perhaps, even courageous, but fundamentally lacking in military sophistication and professional judgment.

Patton intended to prove Montgomery wrong in the most public, dramatic way possible. He would cross the Rine first with minimal preparation at a fraction of the cost and casualties that Montgomery’s elaborate operation would require. Throughout mid-March, as Third Army advanced steadily toward the Rine, Patton prepared methodically for an opportunistic crossing.

He positioned assault boats near the river at multiple potential crossing points. He identified and reckoned several potential crossing sites where German defenses appeared weak. He coordinated with his engineer units about rapid bridge construction procedures, and he waited patiently for the moment when conditions would be favorable for a surprise crossing.

That moment arrived on March 22nd, 1945. Third Army reconnaissance patrols reported that German defenses near the town of Oppenheim, south of Mines, were surprisingly weak and thinly held. The area was lightly defended with minimal German forces. German commanders had concentrated their available reserves further north, expecting the main Allied crossing to occur in Montgomery’s sector, where preparations were obviously massive.

Patton made his decision immediately, without hesitation. Third Army would cross at Oppenheim, not in days or weeks when higher headquarters authorized it. Tonight, March 22nd, 1945. The operation Patton planned was the absolute antithesis of Montgomery’s elaborate approach. There would be no massive artillery bombardment lasting hours to alert the Germans that something was coming.

No airborne drops behind enemy lines. No elaborate coordination of air and ground forces. Just infantry soldiers and canvas assault boats crossing undercover of darkness, relying entirely on surprise and speed rather than overwhelming firepower. Patton staff officers raised serious concerns about the hasty plan. Such a rapid crossing violated standard military doctrine about proper preparation.

Adequate reconnaissance had not been conducted in sufficient detail. Artillery support had not been properly positioned for effective fire support. Medical facilities were not yet established to handle potential mass casualties. If the crossing encountered unexpectedly strong German resistance, casualties could be severe and evacuation difficult.

Patton dismissed every single concern with characteristic confidence. The Germans were weak, disorganized, demoralized. If third army moved fast enough with sufficient surprise, they could establish a solid bridge head before German commanders even realized a crossing was occurring. Speed was more important than meticulous preparation.

Surprise was more valuable than overwhelming firepower. At 2230 hours on March 22nd, elements of the fifth infantry division began crossing the Rine at Oppenheim under cover of darkness. Canvas assault boats, each carrying approximately 12 soldiers with their weapons and equipment, paddled quietly across the dark river.

Germanpositions on the eastern bank remained silent, unaware. No search lights probing the darkness, no machine gun fire, no artillery bombardment. The Germans were completely, utterly surprised. Many German soldiers were sleeping in their positions. Others were in rear areas, believing the front line was stable and secure. When American soldiers emerged suddenly from the darkness and stormed German positions with overwhelming aggression, resistance collapsed almost immediately.

By dawn on March 23rd, Third Army had established a solid, defensible bridge head on the eastern bank of the Rine. Engineers were already constructing pontoon bridges to bring vehicles and heavy equipment across. Armor was preparing to cross in strength and casualties had been remarkably almost unbelievably light. Fewer than 34 soldiers killed or wounded in the entire operation.

Patton had done it. He had crossed the Rine ahead of schedule with minimal preparation and at negligible cost in American lives. It was exactly the kind of audacious, aggressive operation he had built his entire reputation on. Now he just needed to make absolutely sure the world knew about it. Preferably before Montgomery’s elaborate operation even began. March 23rd, 1945.

Morning. Third Army headquarters, Germany. Patton was awake well before dawn, monitoring reports streaming in from the Ryan crossing at Oppenheim. The news was extraordinarily positive, exceeding even his optimistic expectations. The bridge head was expanding rapidly against minimal resistance. German counterattacks were minimal, disorganized, easily repulsed.

Engineers were making rapid progress on pontoon bridge construction. Within hours, armor would be crossing into Germany in significant strength. The operation had succeeded beyond even Patton’s usually optimistic expectations. A river that German propaganda had declared impregnable, that German military doctrine insisted could only be crossed with massive preparation and overwhelming force, had been crossed by a single division using nothing but canvas boats and surprise.

Patton’s first instinct was to share the news immediately, to contact Bradley, to inform Eisenhower, to ensure everyone at higher headquarters knew that Third Army had accomplished what planners had insisted would require weeks of careful preparation. But Patton also recognized shrewdly that timing mattered crucially.

If he announced the crossing too early, higher headquarters might order him to halt, to consolidate, to wait for coordination with other planned operations. Better to establish facts on the ground first, to get enough forces across the Rine that any order to withdraw would be completely impractical to create a situation where the crossing success made further debate pointless.

By midm morning on March 23rd, two complete regiments of the fifth infantry division were across the Rine. The bridge head was approximately 5 kilometers deep and expanding steadily. German forces in the sector were retreating or surrendering without offering serious resistance. Third army was not just across the Rine.

They were advancing into Germany with minimal opposition. Patton decided it was time to inform Bradley of what he’d accomplished. He placed a call to 12th Army Group headquarters. When Bradley came on the line, Patton’s tone was deliberately casual, almost nonchalant, as if reporting routine operations rather than a historic achievement.

Patton informed Bradley matter-of-actly that third army was across the Rine. The bridge head at Oppenheim was secure and expanding. Two divisions would be across by nightfall. Casualties had been negligible. Bradley’s reaction was stunned surprise. is mixed with disbelief. He had not authorized a crossing at Oppenheim.

Third army was supposed to cross at Mines, not Oppenheim, and certainly not without coordination with higher headquarters. Patton explained with characteristic directness that the opportunity had presented itself unexpectedly. German defenses were weak and vulnerable. Waiting for formal authorization would have allowed the Germans time to reinforce.

So he had acted on his own initiative as battlefield commanders must. Bradley was caught between irritation at Patton’s blatant insubordination and genuine admiration for the results achieved. Third Army had accomplished in one night what conventional planning suggested would take weeks of preparation. The Ryan Barrier, Germany’s last major defensive line, had been breached with fewer casualties than a typical day of routine operations.

Bradley made a pragmatic decision. The crossing was already accomplished, a fate accomply. Ordering Patton to withdraw would be pointless and would waste the significant opportunity created. Better to support the operation and exploit the success aggressively. But Patton was not satisfied with simply informing Bradley of the crossing.

By evening on March 23rd, when German forces had begun responding to the Oppenheim crossingwith artillery fire and Luftwaffa attacks on the pontoon bridges, Patton called Bradley again. This time, Patton’s tone was urgent and emphatic, demanding. He demanded that Bradley release news of the crossing to the press immediately without delay.

Patton wanted the entire world to know that Third Army had crossed the Rine before Montgomery’s Operation Plunder even began. Patton’s reasoning was completely transparent to everyone involved. Montgomery had been preparing his Rine crossing for months with enormous resources. The operation was scheduled to begin that very night in just hours.

Montgomery had invited Churchill to witness it personally. British and American newspapers were prepared to cover it extensively as the decisive breakthrough of the European campaign, and Patton wanted to steal Montgomery’s thunder completely and utterly. He wanted newspaper headlines announcing that an American army had already crossed the Rine before the British operation began.

He wanted Montgomery’s meticulously planned operation to be overshadowed by Third Army’s improvised success. Bradley understood exactly what Patton was doing. It was petty, competitive, politically motivated rather than militarily necessary. It would infuriate Montgomery and create serious tension in the Allied command structure.

Eisenhower would be annoyed that Patton was grandstanding rather than maintaining professional cooperation. But Bradley also understood that Patton was fundamentally right about the strategic significance. Third Army’s crossing demonstrated conclusively that the Rine could be breached quickly and cheaply. That elaborate preparation was not always necessary that American forces could achieve dramatic results through speed and audacity that British forces required months to plan.

Bradley authorized release of the news to the press. The announcement was timed deliberately, late enough that Montgomery could not possibly accelerate his operation, early enough that American newspapers would carry the story before British newspapers reported on Operation Plunder. The news reached Montgomery at 11:20 hours on March 23rd, just 13 hours before Operation Plunder was scheduled to begin.

Montgomery was at his forward headquarters conducting final reviews of operational plans when an aid delivered the report that Third Army had crossed the Rine at Oppenheim. Montgomery’s immediate reaction, recorded by multiple witnesses present, was cold and dismissive. He acknowledged that Patton had crossed the Rine somewhere.

He characterized it as very American, impulsive, hasty, lacking in proper planning and coordination. Then he stated flatly that Operation Plunder would proceed exactly as scheduled and would demonstrate the fundamental difference between crossing a river and conducting a proper military operation. The statement revealed Montgomery’s perspective perfectly.

Patton’s crossing at Oppenheim was, in Montgomery’s professional view, merely a raid or reconnaissance in force, not a genuine military operation of any significance. It lacked the scale, the preparation, the comprehensive planning that characterized serious military undertakings. Operation Plunder, by contrast, would be a textbook example of how modern combined arms operations should be executed, massive artillery support, airborne drops, coordinated engineer operations, overwhelming force applied at decisive points. It would be the

crossing that military historians studied and that future officers learned from. in staff colleges. But beneath Montgomery’s professional dismissiveness was genuine fury. Months of careful preparation. Thousands of tons of supplies meticulously accumulated. The promise made to Churchill that this would be the crowning moment of the war.

All of it overshadowed by an American general with canvas boats and sheer audacity. Montgomery’s anger was not just about personal glory or wounded pride. It was about validation of approach, about proving which method of warfare was superior. Montgomery believed wars were won through careful planning and methodical execution.

Patton believed wars were won through speed, aggression, and bold exploitation of fleeting opportunities. The Rine crossing would be cited for decades as evidence for one perspective or the other. and Patton had just scored a decisive point in that fundamental argument by crossing first, faster, and more cheaply than Montgomery’s elaborate operation would manage.

Over the next 48 hours, the contrast between the two crossings became even sharper and more pronounced. Operation Plunder proceeded exactly as planned with textbook precision. The artillery bombardment began on schedule. Infantry crossed in assault boats. Engineers constructed bridges. Airborne forces dropped behind German lines.

The operation was executed with precision and professionalism, but it was also expensive in resources and lives. The preparatory bombardment consumed thousands of tons ofammunition. The airborne drops resulted in significant casualties when some units landed in areas with stronger German resistance than anticipated. The river crossing itself, though successful, caused over 500 casualties.

Meanwhile, Third Army’s bridge head at Oppenheim continued expanding rapidly against minimal opposition. By March 25th, just 3 days after the initial crossing, two entire divisions were across the Rine. Third Army was advancing eastward with minimal resistance, and total casualties remained under 100.

The operational statistics told a stark story that couldn’t be ignored. Montgomery’s crossing had involved 80,000 troops, 5,000 artillery pieces, massive air support, and months of extensive preparation. Casualties exceeded 500. Patton’s crossing had involved one division initially, minimal artillery support, no air support whatsoever, and virtually no preparation.

Casualties were under 100. Newspaper coverage reflected this dramatic contrast. American newspapers carried headlines celebrating Third Army’s spectacular achievement. British newspapers covered Operation Plunder extensively, but could not ignore that Americans had crossed first. The narrative Montgomery had hoped to control, that British forces had delivered the decisive blow across the Rine, was irretrievably lost.

Churchill, who had traveled to Germany specifically to witness Montgomery’s operation, found himself discussing Patton’s crossing as much as plunder. The prime minister was gracious publicly, praising both operations, but privately he was reportedly amused by Patton’s audacity and Montgomery’s obvious discomfort. Montgomery’s fury intensified with each passing hour.

From his perspective, Patton had deliberately sabotaged Operation Plunder’s significance, had acted without proper authorization to steal glory that rightfully belonged to 21st Army Group, had violated the fundamental principle of coordinated operations that was essential to maintaining Allied cooperation. And Montgomery believed firmly that Patton’s insubordination required consequences.

If generals could simply ignore operational plans and launch unauthorized operations whenever they felt like it, military discipline would collapse entirely. Eisenhower needed to take action. By March 26th, Montgomery had made his decision. He would formally recommend to Eisenhower that Patton be relieved of command, not as punishment, though Montgomery certainly felt Patton deserved punishment, but as necessary enforcement of military discipline and coordination.

Montgomery’s argument would be straightforward and logical. Patton had launched a major operation without authorization from Sha. He had violated the agreed operational plan that allocated Rin crossing priority to 21st Army Group. He had done so for personal glory rather than military necessity. And he had damaged Allied cooperation by turning the Rin crossing into a competition rather than a coordinated effort.

Therefore, Montgomery would argue Patton should be removed from command of Third Army and reassigned to a position where his aggressive instincts could be channeled without disrupting theater-wide operations. It was a serious recommendation with potentially significant consequences. Montgomery was Eisenhower’s deputy for ground operations.

His opinion carried substantial weight, and he was prepared to push the issue forcefully. The confrontation between Montgomery and Eisenhower over Patton’s fate would test the limits of Allied cooperation and force Eisenhower to make a choice. Support his difficult but brilliant American general or maintain harmony with his British deputy by sacrificing Patton. March 26th, 1945.

21st Army Group headquarters, Germany. Montgomery composed his message to Eisenhower with the precision he brought to all military matters. The communication would be formal, professional, and unambiguous. It would lay out the case for relieving Patent of Command based on military discipline rather than personal animosity.

The core argument was simple and direct. Patton had launched a major river crossing operation without authorization from Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force. Third Army’s orders had been to advance to mines and prepare for a crossing at that location when formally authorized. Instead, Patton had crossed at Oppenheim, a different location entirely, and had done so days ahead of any approved timeline.

This was not a minor deviation from orders or a reasonable interpretation of intent. It was a fundamental violation of the principle that operations must be coordinated through proper command channels. If every army commander felt free to launch operations based on perceived opportunities rather than coordinated plans, the entire Allied command structure would become dysfunctional.

Montgomery’s message emphasized carefully that this was not about the success or failure of Patton’s operation. The Rine crossing at Oppenheim had succeeded militarily.Montgomery acknowledged that clearly and without reservation, but success did not retroactively justify insubordination. Military discipline required consequences for violations of orders regardless of outcomes.

The message also addressed the impact on allied cooperation. Montgomery pointed out that resources, bridging equipment, artillery, ammunition, air support had been allocated to support operation plunder based on the understanding that it would be the primary rine crossing operation in late March. Patton’s unauthorized crossing had disrupted that resource allocation and complicated coordination between British and American forces.

Furthermore, Montgomery argued Patton’s behavior was part of a disturbing pattern. Throughout the European campaign, Patton had repeatedly pushed boundaries, interpreted orders creatively, and prioritized personal glory over coordinated operations. In Sicily, in France, and now in Germany, Patton had demonstrated that he valued independence over cooperation.

Montgomery’s conclusion was direct and unambiguous. General Patton should be relieved of command of Third Army, not as punishment, per se, but as recognition that his command style was fundamentally incompatible with the requirements of coalition warfare. Patton’s undeniable talents could be utilized in a position where his aggressive instincts would be assets rather than liabilities.

Perhaps commanding occupation forces or planning future operations, but he should not command a field army where coordination with allied forces was essential. The message was sent through secure channels to SHA headquarters on March 26th. Montgomery marked it as requiring Eisenhower’s personal attention and response.

Montgomery was confident his argument was sound and compelling. He had framed the issue in terms of military discipline and operational coordination rather than personal rivalry. He had acknowledged Patton’s tactical success while maintaining that success did not excuse insubordination. And he had positioned the recommendation as necessary for maintaining allied cooperation, an argument that would resonate with Eisenhower, who had spent years managing coalition politics.

But Montgomery also knew he was taking a significant risk. Eisenhower might not support relieving Patton. American public opinion strongly favored Patton. He was seen as an aggressive, victorious general who got results. Relieving him would be politically controversial in the United States. Still, Montgomery believed the principle mattered more than politics.

If Eisenhower wanted to maintain effective command and control over allied forces, he needed to enforce discipline, and that meant consequences for generals who operated independently rather than cooperatively. While Montgomery’s message was in transit to SHA headquarters, the strategic situation continued evolving rapidly. Third Army’s bridge head at Oppenheim was now 15 km deep.

Two full divisions were across the Rine and advancing eastward. Patton had already begun planning the next phase, a rapid advance toward Frankfurt and then deeper into Germany. Operation Plunder was also proceeding successfully. By March 26th, British and Canadian forces had established solid bridge heads and were expanding eastward.

The operation was achieving all its objectives, though at higher cost than Patton’s crossing, but the narrative had been set irreversibly. Newspaper coverage focused on Patton’s dramatic crossing as the breakthrough moment. Operation Plunder was reported as a follow-on operation, important and successful, but not the decisive blow that Montgomery had intended it to be.

This narrative infuriated Montgomery, not just because of wounded pride, but because he believed it was strategically misleading. Patton’s crossing at Oppenheim was tactically brilliant, but strategically secondary. The decisive blow against German defenses was being delivered by 21st Army Group in the north, where German reserves were concentrated, and where the advance would lead directly to the rurer industrial region, Germany’s economic heartland.

But newspapers did not report nuanced strategic analysis. They reported dramatic stories. And Patton crossing the Rine with canvas boats made a better story than Montgomery’s methodical operation. Montgomery’s frustration was compounded by reports of Patton’s behavior after the crossing. Two days after establishing the bridge head, Patton had personally crossed the rine on one of the pontoon bridges Third Army engineers had constructed.

Multiple witnesses reported that halfway across the bridge, Patton had stopped, walked to the edge, and urinated into the rine. When asked about his action, Patton had reportedly stated he had been waiting a long time to do that, to literally relieve himself on Germany’s last defensive barrier. It was vintage patent, crude, theatrical, designed for maximum symbolic impact.

Montgomery found the gesture vulgar and unprofessional. It epitomized everythinghe disliked about Patton. The showmanship, the vulgarity, the prioritization of personal gesture over military professionalism. But American soldiers loved it. The story spread rapidly through third army and then throughout American forces in Europe. It became legend.

Patton literally urinating on Hitler’s Germany, showing contempt for enemy defenses and German military capability. The contrast between Montgomery and Patton could not have been sharper. Montgomery conducted war like a chess match. Carefully planned moves, calculated risks, emphasis on position and resources. Patton conducted war like a cavalry charge, speed, aggression, dramatic gestures, emphasis on morale and momentum.

Neither approach was inherently superior. Both had strengths and weaknesses, but they were fundamentally incompatible command philosophies, and the Rine crossing had become a referendum on which approach was more effective. From Montgomery’s perspective, the answer should have been obvious. His operation had involved proper planning, adequate preparation, and coordinated execution.

It had achieved all objectives with acceptable casualties. It was how modern military operations should be conducted. But from the public perspective and increasingly from the military perspective, Patton’s approach had won. He had crossed faster, cheaper, and more dramatically. He had demonstrated that speed and audacity could achieve results that elaborate planning could not match.

Montgomery’s message reached Eisenhower’s headquarters on the evening of March 26th. It was marked urgent and for the Supreme Commander’s eyes only. Staff officers recognized its sensitivity and ensured it was delivered to Eisenhower personally. Eisenhower read Montgomery’s recommendation that Patton be relieved of command.

He read the arguments about military discipline and coordination. He read the references to Patton’s pattern of independent action and disregard for proper channels. And Eisenhower faced exactly the dilemma Montgomery had anticipated. Should he support Montgomery’s legitimate concerns about military discipline? Or should he protect Patton, whose results were undeniable, even if his methods were problematic? The decision would define Eisenhower’s approach to managing his most difficult and most effective subordinate.

It would also send a message about what mattered more in the final months of the war, cooperation and coordination, or results and speed. Eisenhower did not respond to Montgomery’s message immediately. He needed to think carefully about his response to consider the military implications, the political ramifications, and the personal relationships involved.

But Eisenhower also knew that whatever he decided, someone would be furious. If he relieved Patton, American forces would see it as capitulation to British pressure and favoritism toward Montgomery. If he refused to relieve Patton, Montgomery would see it as tolerance of insubordination and favoritism toward Americans.

There was no decision that would satisfy everyone. Eisenhower would have to choose which principle mattered most and accept the consequences of that choice. And privately, Eisenhower had already begun forming his conclusion because he knew something about Patton that Montgomery perhaps did not fully appreciate. Patton was not just a talented tactical commander.

He was a force multiplier, a general whose presence and personality drove soldiers to achieve things they did not think possible. The Rine crossing at Oppenheim exemplified this perfectly. No other American general would have attempted such an operation with so little preparation. No other general would have succeeded with so few casualties.

Patton had done it because he believed it was possible and his soldiers believed in him. Could Eisenhower afford to lose that, especially now in the final months of the war when aggressive pursuit of retreating German forces could end the conflict quickly? Eisenhower’s answer was beginning to crystallize and it was an answer Montgomery would not like.

March 27th, 1945. SHAF headquarters, Reigns, France. Eisenhower sat at his desk with Montgomery’s message in front of him. He had read it multiple times, considering the arguments from every angle. The recommendation was serious and formally presented. It demanded a substantive response. Eisenhower’s position as supreme commander of Allied Expeditionary Forces required him to balance competing demands constantly.

Military effectiveness, political sensitivity, allied cooperation, national interests, personal relationships. Every decision involved trade-offs, and every trade-off created dissatisfaction somewhere. The patent question epitomized these competing demands. Montgomery’s arguments were legitimate.

Patton had operated outside authorized parameters. He had launched a major operation without coordination through proper channels. His actions had complicated resource allocation and disrupted planned operations. These werereal concerns. Military organizations require discipline and coordination to function effectively.

Commanders who operate independently based on their own judgment rather than coordinated plans create chaos. If Patton’s behavior was accepted without consequences, other commanders might conclude they too could ignore directives whenever convenient. But Eisenhower also had to consider results. Patton’s Rine crossing had achieved in one night what conventional planning suggested would require weeks.

Third Army had breached Germany’s last major defensive line with minimal casualties and was now advancing rapidly into German territory. The strategic impact was significant and favorable. Moreover, Eisenhower understood something about Patton that was difficult to articulate in formal military language.

Patton had an almost supernatural ability to assess battlefield situations and exploit fleeting opportunities that more cautious commanders would miss entirely. His instincts were extraordinarily accurate. His timing was impeccable. His willingness to take calculated risks produced results that methodical approaches could not match.

This ability came with costs. Patton was difficult to manage. He chafed under restrictions. He prioritized independence over coordination. He measured success in terms of ground gained and enemies destroyed rather than adherence to plans. Working with Patton required constant vigilance and frequent intervention.

But Eisenhower had been managing Patton for years in North Africa, in Sicily, across France, and now in Germany. He had learned how to channel Patton’s aggressive instincts productively while preventing those instincts from causing disasters. It was exhausting and frustrating, but it was also effective. The question now was whether the benefits of keeping Patton in command outweighed the costs of his insubordination, whether his tactical brilliance justified the disciplinary violations, whether results excused methods.

Eisenhower also had to consider the political dimension. Patton was enormously popular with American soldiers and the American public. He was seen as the epitome of aggressive American military spirit. Bold, confident, victorious. Relieving him would create a firestorm of criticism in the United States.

American newspapers would portray it as British jealousy, as Montgomery using his position to eliminate a rival, as prioritizing proper procedure over winning the war. The political fallout would be severe and would complicate Eisenhower’s relationship with the US War Department and Congress. Conversely, refusing Montgomery’s recommendation would strain Allied relations.

Montgomery would see it as favoritism toward American commanders, as tolerance of indiscipline because the offender was American rather than British, as undermining Montgomery’s authority as Eisenhower’s deputy for ground operations. There was no decision that would avoid negative consequences. Eisenhower had to choose which consequences he was willing to accept.

He drafted his response to Montgomery carefully. The message acknowledged Montgomery’s concerns about coordination and discipline. It recognized that Patton’s rin crossing had not followed approved procedures. It accepted that better communication and coordination would have been preferable. But the message also made clear that Eisenhower would not relieve patent of command.

The reasons were both military and practical. Militarily, Third Army’s performance had been exceptional throughout the campaign. Patton’s aggressive leadership had produced results that justified continued confidence in his command. Practically, the war was entering its final phase. German forces were collapsing. The priority now was rapid exploitation to prevent German forces from establishing new defensive lines or continuing prolonged resistance.

This was exactly the kind of situation where Patton’s strengths were most valuable. Eisenhower’s message emphasized that he would address coordination issues with Patton directly. Future operations would require better communication with SHA headquarters, but removing Patton from command was not warranted given his performance and the current strategic situation.

The response was diplomatic but firm. Eisenhower was supporting Patton despite the violations Montgomery had identified. The message would not satisfy Montgomery, but it reflected Eisenhower’s judgment about what best served Allied interests in the final months of the war. The message was transmitted to 21st Army Group headquarters on March 28th.

Montgomery’s reaction was predictably negative. He saw Eisenhower’s decision as prioritizing American interests over military discipline, as failing to enforce the standards of coordination and cooperation that coalition warfare required. But Montgomery also recognized he had lost the argument. Eisenhower had made his decision.

Further protest would only create additional friction without changing the outcome. Montgomeryaccepted the decision professionally, though his frustration with Patton and his skepticism about Eisenhower’s judgment both intensified. The tension between Montgomery and Patton would continue for the remainder of the war. They would never become cordial.

They would never genuinely respect each other’s approaches, but they would function professionally within the command structure Eisenhower maintained. Meanwhile, Patton was informed of Montgomery’s recommendation and Eisenhower’s response. His reaction mixed satisfaction and resentment. Satisfaction that Eisenhower had supported him.

Resentment that Montgomery had attempted to have him removed. Patton’s comment about the situation, relayed through multiple sources, captured his perspective on Eisenhower’s management of Allied politics. When Patton learned that Eisenhower had allocated more supplies to Montgomery’s operation than to Third Army, he had reportedly muttered that Eisenhower was the best general the British had.

It was a cruel joke, suggesting Eisenhower favored British interests over American, but it reflected Patton’s frustration with the constraints coalition warfare placed on his operations. Eisenhower had to balance American and British interests. Patton only cared about Third Army’s objectives. Eisenhower understood this about Patton.

He knew Patton’s comment was how Patton processed frustration rather than serious criticism. The two men had known each other for decades. They understood each other’s strengths and limitations. Their relationship was built on mutual respect despite frequent tension. The Rine crossing controversy gradually faded as both operations succeeded and the focus shifted to the next phase of operations.

Third Army continued its rapid advance eastward. British and Canadian forces advanced north of the ruer. American and British forces were now deep inside Germany and final victory was approaching. But the Rine crossing left a lasting legacy in military history and in popular memory. It became the definitive example of the contrast between Montgomery’s methodical approach and Patton’s audacious style.

Military historians would debate for decades which approach was more effective. The statistical comparison was stark. Montgomery’s operation plunder involved 80,000 troops, 5,000 artillery pieces, extensive air support, and months of preparation. It achieved all objectives but cost over 500 casualties. Patton’s crossing at Oppenheim involved one division initially, minimal fire support, no preparation, and cost fewer than 100 casualties.

The number suggested Patton’s approach was more efficient. But efficiency was not the only measure of military operations. Montgomery’s crossing had strategic objectives beyond simply getting across the river. It was designed to draw German reserves and enable a massive breakthrough. Patton’s crossing was opportunistic exploitation of weak enemy defenses.

Both approaches had value. Both achieved important objectives. But the public perception was clear. Patton had won the race to cross the Rine, and he had done so in spectacular fashion. The image of Patton urinating into the Rine became legendary. It was crude and theatrical. But it captured something essential about Patton’s personality and his approach to war.

He showed contempt for obstacles that others considered formidable. He reduced Germany’s last great defensive barrier to something he could literally relieve himself on. American soldiers loved the gesture because it expressed what they felt. That German defenses were no longer intimidating. That victory was inevitable.

That the enemy, who had seemed so powerful in 1944, was now beaten and demoralized. Montgomery found the gesture vulgar and unprofessional. But then Montgomery and Patton had fundamentally different concepts of what military professionalism meant. Montgomery valued planning, coordination, and adherence to established procedures.

Patton valued results, speed, and moralebuilding gestures. Neither was wrong. They were simply different commanders with different strengths operating in different contexts. Montgomery excelled at setpiece battles where preparation and resources could be concentrated. Patton excelled at exploitation and pursuit where speed and aggression were paramount.

Eisenhower’s genius was recognizing these differences and using both commanders effectively. He gave Montgomery responsibility for operations that required careful planning and coordination. He gave Patton responsibility for operations that required speed and audacity. And he managed the inevitable conflicts between them to prevent those conflicts from undermining the overall campaign.

The Rin crossing episode demonstrated Eisenhower’s approach perfectly. He did not punish Patton for insubordination because Patton’s insubordination had produced valuable results. But he also communicated clearly to Patton that better coordination was expected in futureoperations. He balanced discipline with pragmatism.

This was not textbook leadership. Military doctrine said commanders who violated orders should face consequences. But Eisenhower understood that doctrine was a guide, not an absolute rule. Sometimes exceptional commanders required exceptional management approaches. By early April 1945, Third Army was racing across central Germany.

British and Canadian forces were encircling the ruer. American forces were approaching the Elber River. German resistance was collapsing. The war was entering its final weeks. And when historians later analyzed how the war was won, the Rine crossings would feature prominently. Montgomery’s careful preparation at Wel Patton’s audacious dash at Oppenheim.

Both contributed to breaking German defenses and enabling the final Allied offensives. But in popular memory, it was Patton’s crossing that endured. The story of a general who crossed the Rine with canvas boats and sheer audacity. Who beat his rival to the punch, who urinated in the river as a gesture of contempt, who proved that sometimes speed and boldness matter more than preparation and caution.

Montgomery completed his elaborate crossing exactly as planned. It was executed with precision and achieved all objectives. But the headlines were old news. Patton had already crossed. And somewhere in Germany, advancing toward Frankfurt and beyond, Patton was almost certainly smiling. He had done exactly what he always wanted to do.

Prove that speed and daring still won wars. That American audacity was superior to British caution. That he, George Patton, was the finest tactical commander of his generation. Eisenhower allowed him that satisfaction because Eisenhower understood something fundamental about Patton. He needed to win, to compete, to prove himself constantly.

It was exhausting to manage. It created endless headaches. But it also produced results that more manageable commanders could not match. So Eisenhower kept Patton in command, managed his ego, channeled his aggression, tolerated his insubordination when it produced victories, and dealt with the political fallout of having a subordinate who was brilliant, difficult, and absolutely essential to winning the war.

The Rin crossing controversy ended not with clear resolution, but with practical acceptance. Montgomery believed Patton should have been relieved. Patton believed Montgomery was jealous and obsolete. Eisenhower believed both had value and managed them accordingly. And the war continued, racing toward its conclusion with two very different generals, proving that there was more than one way to win battles, even if they could never agree on which way was better.

If this story of rivalry, different command philosophies, and Eisenhower’s difficult decision has fascinated you, subscribe to WW2 Gear right now. Hit that notification bell so you never miss our deep dives into the critical moments and command decisions that shaped the war. Give this video a like if you appreciate how we bring these command confrontations to life.

Share it with anyone who loves military history or wants to understand how coalition leadership really works. Drop a comment and tell us, was Eisenhower right to keep Patton in command despite his insubordination, or should he have supported Montgomery’s recommendation? And where are you watching from? We love hearing from our global community of history enthusiasts.

Remember, sometimes the most difficult subordinates are also the most effective when their strengths are properly channeled. Eisenhower understood that and the Rine crossing proved

News

Washington Commanders Are Hiring Former Detroit Lions QB As Their New Offensive Coordinator

Washington Commanders Are Hiring Former Detroit Lions QB As Their New Offensive Coordinator January 9, 2026, 9:21pm EST 2K+ • By Alex Hoegler The…

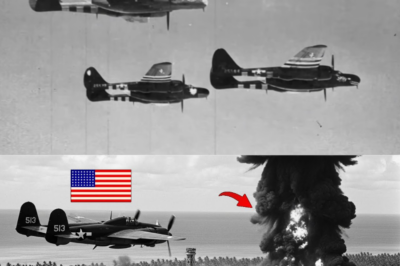

Japanese Couldn’t Believe One P-61 Was Hunting Them — Until 4 Bombers Disappeared in 80 Minutes

Japanese Couldn’t Believe One P-61 Was Hunting Them — Until 4 Bombers Disappeared in 80 Minutes At 2340 on December…

They Mocked His ‘Medieval’ Bow — Until He Killed 7 German Sergeants in 3 Days

They Mocked His ‘Medieval’ Bow — Until He Killed 7 German Sergeants in 3 Days At 0742 on May 27th,…

New Angle of Brutal Warriors Fan Brawl Goes Viral as One Spectator Appears to Enjoy the Chaos [VIDEO]

New Angle of Brutal Warriors Fan Brawl Goes Viral as One Spectator Appears to Enjoy the Chaos [VIDEO] January 9,…

They Sent 40 ‘Criminals’ to Fight 30,000 Japanese — What Happened Next Created Navy SEALs

They Sent 40 ‘Criminals’ to Fight 30,000 Japanese — What Happened Next Created Navy SEALs At 8:44 a.m. on June…

State Farm’s Sneaky Move: Yanks Patrick Mahomes’ Ad Off the Air—But We’ve Got the Deleted Commercial Right Here for You [VIDEO]

State Farm’s Sneaky Move: Yanks Patrick Mahomes’ Ad Off the Air—But We’ve Got the Deleted Commercial Right Here for You…

End of content

No more pages to load