What Japanese Commanders Really Thought About US Marines

At 0615 hours, on August 21st, 1942, Colonel Kiyonau Ichiki stood at the edge of a coconut grove on Guadalcanal, staring across a shallow creek at the American defensive line he was about to attack. He had 917 of Japan’s finest soldiers behind him, men who had trained for years, men who had conquered territories across Asia without defeat.

Men who believed, as Ichiki himself believed, that no Western force could stand against them. The Americans on the other side of that creek were United States Marines. Ichiki had studied them before departure. He knew what Japanese intelligence said about these men. They were soft. They were undisciplined. They lacked the warrior spirit that defined Japanese soldiers. They were soft. They were undisciplined.

They lacked the warrior spirit that defined Japanese soldiers. They would break at the first sign of a determined assault. In approximately six hours, 800 of Ichiki’s soldiers would be dead, and everything Japan thought it knew about American fighting men would begin to unravel. This is the story of how Guadalcanal shattered one of the most dangerous beliefs in military history, the conviction held by Japanese commanders that American Marines were incapable of real combat. To understand what happened on Guadalcanal, you have to understand

what Japanese military leaders believed about Americans before the war began. For decades, Japanese military doctrine had been built on a concept called Yamato Damashii, the spirit of Japan. This was more than simple nationalism. It was a foundational belief that Japanese soldiers possessed a spiritual superiority that could overcome any material disadvantage.

Where Western nations relied on machines and firepower, Japan relied on the indomitable will of its warriors. The roots of this belief stretched back to the ancient mythology recorded in the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, texts that described the Japanese people as descendants of the sun goddess Amaterasu.

The emperor himself was considered divine, a living connection to the heavens. Japanese soldiers did not merely fight for their country. They fought for a sacred bloodline stretching back thousands of years. This philosophy became central to Japanese military thinking in the early 20th century. The stunning victory over Russia in 1905 seemed to confirm everything that Japanese leaders believed about themselves.

A smaller Asian nation had defeated a European power through superior fighting spirit. Russian armies with modern weapons and industrial backing had been humiliated by Japanese soldiers who demonstrated an apparent willingness to die that their opponents could not match. The lesson was clear. Material strength meant nothing against men willing to sacrifice everything for their emperor.

The Russo-Japanese War became the template for how Japan would approach future conflicts. Spirit would triumph over steel. Will would defeat weapons. By the 1930s, this belief had hardened into doctrine. Japanese officers were taught that Western soldiers, particularly Americans, were spiritually weak.

They were products of a soft, materialistic culture that prioritized individual comfort over collective sacrifice. They would not stand and fight when the situation became desperate. They would surrender. They would run. The early months of the Pacific War appeared to validate this assessment completely. When Japanese forces attacked the Philippines in December 1941, American and Filipino defenders collapsed within weeks.

The fortified positions that were supposed to hold for months fell in days. Bataan and Corregidor became symbols not of American resistance, but of American failure. Tens of thousands of prisoners were taken in one of the worst military disasters in American history.

At Singapore, which Winston Churchill called the worst disaster in British military history, over 80,000 Allied troops surrendered to a Japanese force half their size. British commanders had believed Singapore was impregnable. The Japanese proved them wrong in a matter of weeks. General Tomoyuki Yamashita’s forces attacked down the Malay Peninsula with a speed and ferocity that overwhelmed defenders at every turn.

In the Dutch East Indies, in Hong Kong, in Burma, the pattern repeated. Western forces consistently failed to match Japanese determination. Colonial armies that had maintained order for generations crumbled when faced with Japanese soldiers who seemed to welcome death. At Wake Island, a tiny American garrison had held out for over two weeks against overwhelming odds before finally surrendering.

Japanese commanders noted this resistance with interest but did not draw broader conclusions from it. Wake was an anomaly. The Marines there had simply been trapped with nowhere to run. Japanese commanders drew what seemed like obvious conclusions from the pattern of victories. The Americans were exactly what they had always believed them to be. They had better equipment, more supplies, bigger ships.

But they lacked the one thing that actually mattered in war. They lacked the will to fight. This belief extended specifically to the United States Marine Corps. Japanese intelligence had studied the Marines and found nothing impressive. They were a small force, poorly equipped compared to the Army, with no recent combat experience.

They had not faced a serious enemy since the First World War. They were, in the assessment of Imperial General Headquarters, garrison troops playing at being soldiers. The Marine Corps in 1942 was indeed a small service, numbering fewer than 70,000 men at the start of the war.

It had spent the interwar years in relative obscurity, fighting small wars in Central America and the Caribbean. The battles of Nicaragua and Haiti were not the stuff of military legend. Japanese planners saw nothing in that record to suggest the Marines would be formidable opponents. What they missed was the transformation the Corps had undergone in the 1930s. Marine officers had developed new doctrines for amphibious warfare, recognizing that the Pacific War they expected would require the ability to assault fortified beaches. They had created specialized equipment and training programs. They had built a force

specifically designed to fight the kind of war that was coming. More importantly, they had developed a culture that emphasized individual initiative, small unit leadership, and the ability of junior Marines to continue fighting even when communications broke down and plans fell apart. This culture would prove decisive on Guadalcanal.

Colonel Ichiki personally held the views common to Japanese officers about American capabilities. Japanese military assessments had characterized American Marines as effeminate and cowardly, lacking the warrior spirit of Japanese soldiers. When he received orders to retake Guadalcanal from the Americans who had landed there in early August 1942, he saw it as an opportunity for glory, not a genuine military challenge.

The Americans had seized an airfield the Japanese were building on the island. They needed to be pushed back into the sea. Ichiki was told to wait for the rest of his regiment before attacking, but he saw no need. His first echelon of 900 men would be sufficient. Against marines, what more could possibly be required? Major General Alexander Vandergrift had no idea what the Japanese thought of his marines. He was too busy trying to keep them alive.

Vandegrift was 54 years old, a veteran of campaigns in Nicaragua, Haiti, and China. He had spent his entire adult life in the Marine Corps. He knew what his men were capable of, but he also knew they had never faced anything like what awaited them in the Solomon Islands.

He had been promised six months to train his division before seeing combat. He got three weeks. When Operation Watchtower, the invasion of Guadalcanal, was announced, his men were scattered across the Pacific with equipment still being unloaded in New Zealand. There was no time for proper planning, no adequate intelligence on Japanese defences, and a rehearsal landing in the Fiji Islands that Vandegrift later called a complete disaster.

The rehearsal was so poorly executed that one officer remarked experienced logistical planners would later have pronounced the entire Guadalcanal operation as impossible. The 1st Marine Division itself was a mixture of veterans and raw recruits. Many of the men had enlisted after Pearl Harbor, motivated by rage at the Japanese attack. They had minimal training and no combat experience.

They did not know what jungle warfare looked like. They did not understand the diseases that awaited them. They had never faced an enemy who would rather die than surrender. On August 7, 1942, 11,000 Marines landed on Guadalcanal and the nearby islands of Tulagi and Florida. They achieved complete surprise.

The Japanese construction workers and small garrison, mostly Korean labourers with a small guard detachment, fled into the jungle when American warships opened fire on their positions. By nightfall on August 8th, the Marines had secured their primary objective, the unfinished airfield that would soon be named Henderson Field after Major Lofton Henderson, a Marine aviator killed at the Battle of Midway. The landings had been easier than anyone expected.

But the marines were about to learn that taking Guadalcanal was far simpler than holding it. Then everything went wrong. On the night of August 8th and 9th, a Japanese naval force surprised and devastated the Allied cruiser screen at the Battle of Savo Island. Four Allied cruisers were sunk in one of the worst naval defeats in American history. Over 1,000 sailors died.

The naval commander, Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, fearing further losses to his aircraft carriers, withdrew the fleet, taking with it most of the Marines’ supplies and equipment that had not yet been unloaded. The Marines were bitter about being abandoned. Decades later, veterans would still speak of the withdrawal with anger. One commemorative medal privately minted after the battle showed a hand in an admiral’s sleeve, dropping a hot potato into the arms of a Marine, with the inscription, Fasciat Georgius, meaning, Let George Do It. Vandegrift’s Marines were stranded.

Georgius, meaning, let George do it. Vandegrift’s marines were stranded. They had captured their objective, but now they had to hold it with limited ammunition, limited food, and no naval support. Half of their supplies were still aboard the ships that had withdrawn. They had no heavy equipment. They had no reinforcements coming.

They were alone on an island that Japanese forces were already moving to retake. The Marines established a defensive perimeter around Henderson Field and began the gruelling work of finishing the airfield with captured Japanese equipment. They salvaged what supplies they could find. They captured Japanese rice stores and made that their primary food source.

They dug foxholes in the volcanic soil and waited for the counterattack they knew was coming. The jungle around them was hostile in ways they had never imagined. The heat was oppressive, the humidity suffocating. Mosquitoes carrying malaria swarmed everywhere. Within weeks, disease would disable more Marines than Japanese bullets.

But they held their perimeter and they kept working on the airfield. On August 20, the first American aircraft landed at Henderson Field. These planes, part of what would become known as the Cactus Air Force after the Allied codename for Guadalcanal, would prove essential to holding the island. But they were not yet ready when the first Japanese counterattack arrived.

They did not have to wait long. Colonel Ichiki landed at Taivu Point on the night of August 19th with 917 men. Japanese aerial reconnaissance had reported few American troops visible and no large ships nearby. A senior staff officer from Rabaul had personally flown over the marine positions on August 12th and seen almost nothing, concluding that the Americans had withdrawn most of their forces.

Imperial headquarters believed the Marines had abandoned Guadalcanal, leaving only a token garrison. Ichiki was told he might face as few as 2,000 defenders. In reality, there were 11,000 Marines on Guadalcanal. But Ichiki did not know this, and even if he had known, it might not have changed his plans. He had absolute faith in the superiority of his soldiers. His regiment was no ordinary unit.

The 28th Infantry Regiment had originally been designated to assault Midway Island. When the naval battle of Midway ended that possibility, the regiment was redirected to Guadalcanal. These were men who had been trained for the most difficult kind of operation, a contested amphibious landing against fortified positions. They were among the best Japan had.

Ichiki left 125 men as a rear guard and immediately began marching toward Henderson Field with the rest of his force. His orders had been to wait on the beachhead for the remainder of his regiment, which would arrive on slower transport ships in a few days. He ignored them. The marines would collapse at the first assault.

There was no need to wait for reinforcements that would only share in the glory that rightfully belonged to his men. What Ichiki did not know was that the mar were aware he was coming. A Coast Watcher scout named Jacob Voza, a former sergeant major in the British Solomon Islands Police Force, had been captured by Japanese soldiers while gathering intelligence.

The Japanese found an American flag hidden in his loincloth and demanded information about Marine positions. Voza refused to talk. The Japanese tied him to a tree and used him for bayonet practice. They stabbed him seven times, in his arms, throat, shoulder, face, chest and stomach. He was not dead.

After the Japanese moved on, Voza chewed through his ropes and crawled through the jungle for miles, bleeding from his wounds. He reached the Marine lines and warned them of the approaching attack minutes before Ichiki’s assault began. Voza would survive his wounds and continue to serve alongside the Marines throughout the campaign.

He would later receive the Silver Star and be made an Honorary Sergeant Major in the Marine Corps. At approximately 0130 hours on August 21, Ichiki launched his assault across the sandbar, at the mouth of Alligator Creek, which American maps incorrectly labeled as the Teneru River. The Marines were waiting. The first wave of Japanese soldiers charged across the sandbar screaming banzai, their bayonets fixed, expecting the Americans to flee in terror.

banzai, their bayonets fixed, expecting the Americans to flee in terror. This was how it had always worked. This was how it was supposed to work. What happened next shocked the Japanese soldiers who survived it. The Marines did not run. They did not surrender. They did not panic in the face of a determined night assault.

Instead, they held their positions and poured devastating fire into the attacking Japanese. Machine gun positions along the creek opened up with withering accuracy. The water-cooled.30-caliber guns, manned by Marines who had trained extensively with the weapons, cut through the assault waves. Japanese soldiers fell by the dozens, then by the hundreds. The sandbar became a killing ground.

Ichiki had expected the Americans to break when they saw Japanese soldiers charging with fixed bayonets, screaming battle cries. This was what always happened. Western troops could not withstand the psychological pressure of a Banzai charge. Their nerve would fail. They would flee. The Marines did not flee.

Artillery batteries that had registered their targets before nightfall dropped shells directly on the assault formations. The accuracy of the American fire astounded the Japanese officers who survived the battle. Every approach route seemed to be covered. Every advance was met with coordinated fire.

When Japanese soldiers managed to reach the Marine lines, they were met with close combat that matched their own ferocity. Marines fought with rifles, pistols, bayonets, and bare hands. They gave ground grudgingly, then counterattacked to retake lost positions. They showed no fear and asked for no quarter.

One Marine machine gunner, Private Al Schmid, was wounded early in the battle when a grenade exploded near his position. Shrapnel struck him in the face, destroying both his eyes. Blinded, he continued to operate his weapon by touch alone. Guided by his assistant gunner who directed his fire toward the sound of approaching Japanese, he remained at his post until dawn. By sunrise, the attack had failed completely.

Ichiki’s men had achieved nothing except their own destruction, but the battle was not over. As the sun rose, Vandergrift ordered a counter-attack. Marines from the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines crossed the creek upstream and swung around to encircle the surviving Japanese. Light tanks joined the assault, M3 Stuart tanks that the Marines called their Iron Cavalry.

The encirclement was methodical and brutal. Japanese soldiers who had survived the night found themselves trapped in a coconut grove, with Marines closing in from all sides. Some tried to swim to safety and were shot in the water. Some fought to the last bullet and then charged with bayonets. Some committed suicide rather than face capture. The tanks rolled through the coconut grove, their machine guns chattering, crushing wounded Japanese soldiers beneath their treads.

The Marines who followed them showed no more mercy than the Japanese had shown in their conquests across Asia. The American press would later sanitise this, but the reality was brutal. The Marines had absorbed the shock of Japanese tactics and responded with overwhelming violence. One Marine who participated in the battle later described the aftermath.

The bodies lay in clusters or heaps before the gun pits commanding the sand spit, as though they had not died singly but in groups. Moving among them were the souvenir hunters, picking their way delicately as though fearful of booby traps. By five in the afternoon on August 21st, the Battle of the Teneru was over.

Of Ichiki’s original 917 men, approximately 800 were dead. The survivors, perhaps 128, escaped into the jungle and eventually made their way back to Taivu Point. Marine casualties were 35 killed and 75 wounded. The exchange rate was staggering.

For every American who fell, the Japanese had lost more than seven men. This was not supposed to happen. This was not what Japanese doctrine predicted. Colonel Ichiki burned his regimental colours to prevent their capture, a profound disgrace in Japanese military culture. He then either died fighting in the final stages of the battle or committed ritual suicide shortly thereafter. Accounts differ, and the exact circumstances of his death remain uncertain.

What is certain is that he did not survive to explain why his assault had failed so catastrophically. When news of the Ichiki detachment’s destruction reached Rabaul, Japanese commanders reacted with disbelief. The reports had to be wrong.

A Japanese infantry regiment could not have been annihilated by American marines. This was simply not possible. Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo had the same reaction. The defeat was so unexpected that many officers refused to accept it. Something must have gone wrong with Ichiki’s plan. Perhaps he had attacked the wrong position. Perhaps his men had encountered unexpected terrain.

Perhaps the reports were exaggerating the casualties. The Marines themselves could not have been the problem. Some Japanese officers later expressed frustration at this denial. Imperial General Headquarters continued to belittle the enemy on Guadalcanal, and assumed that once Japanese forces landed successfully, the Marines would surrender.

that once Japanese forces landed successfully, the Marines would surrender. This underestimation would prove catastrophic. This denial had fatal consequences. Instead of reassessing their assumptions about American fighting capability, Japanese commanders concluded that Ichiki had simply sent too few men. The solution was obvious. Send more.

Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi was given command of the next attempt to retake Henderson Field. He would lead approximately 6,000 men from the 35th Infantry Brigade, a veteran unit that had fought successfully in Borneo and the Philippines. Kawaguchi himself had a reputation as an unconventional thinker, a commander willing to question orders and adapt to circumstances. His soldiers respected him.

He was known to be unusually solicitous of his men’s welfare. Surely this force would succeed where Ichiki had failed. Surely Kawaguchi’s experience and tactical flexibility would overcome whatever advantages the marines possessed. Kawaguchi was more thoughtful than Ichiki. He had studied the reports from the Tenaru carefully.

He understood that the marines were better prepared than expected. He understood that a frontal assault across open ground would be suicide, but he still believed that a properly planned night assault from an unexpected direction would overwhelm them. His plan was actually quite sophisticated.

Instead of attacking across the obvious approaches that the Marines had fortified, Kawaguchi would march his men through the jungle to attack from the south, where the Marine perimeter was more lightly defended. A ridge running down toward Henderson Field provided a natural avenue of approach. If his men could seize that ridge in a surprise night attack, they could pour through the breach and overrun the airfield before the Marines could react.

The ridge had no name in September 1942. After the battle, it would be called Edson’s Ridge, or Bloody Ridge. It would become one of the most famous pieces of ground in Marine Corps history. Kawaguchi landed his forces on Guadalcanal in late August and early September, delivered by destroyers and barges that ran the gauntlet of American air attacks. The approach march through the jungle was far more difficult than he had anticipated.

His men struggled through terrain that seemed designed to destroy military formations. Trails disappeared. Streams blocked routes. The dense vegetation made coordination between units nearly impossible. Units became separated. Supplies ran out. Soldiers arrived at their assault positions exhausted, hungry, and disorganized.

Some battalions were so lost in the jungle that they never reached the attack positions at all. Barge convoys carrying heavy equipment were spotted by American aircraft and destroyed, leaving Kawaguchi without artillery support. Despite these problems, Kawaguchi remained confident.

He still believed that Japanese fighting spirit would overcome any obstacle. He told his officers that the Marines would surrender once the attack achieved breakthrough. They would not be able to sustain resistance against determined Japanese soldiers fighting at close quarters. The spiritual superiority of his men would prove decisive.

On the night of September 12, 1942, Kawaguchi launched his assault. Defending the ridge was a mixed force of about 800 Marines, primarily from the 1st Raider Battalion and the 1st Parachute Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Merritt Edson. These were among the best-trained men in the Marine Corps, specialists in close combat and irregular warfare, who had already seen action at Tulagi and on patrol operations around Guadalcanal. Edson was a remarkable officer.

He had fought in Nicaragua against Sandino’s guerrillas, and earned a reputation as one of the most aggressive commanders in the Marine Corps. His red hair had given him the nickname Red Mike. His men both feared and respected him. They knew he would ask nothing of them, that he would not do himself.

Edson had positioned his men carefully along the ridge, with pre-registered artillery targets covering the likely approach routes. He suspected an attack was coming. Japanese air raids had been hitting the ridge specifically, which suggested it was an objective. He had his men dig deep and prepare for a fight.

The Japanese attacked in waves, screaming their battle cries, throwing themselves against the marine positions with fanatical determination. The jungle erupted in gunfire, flares illuminated the attacking formations, turning the night into a hellscape of shadows and muzzle flashes. And again, the marines did not break. The fighting on Bloody Ridge was among the most intense of the entire war.

Japanese soldiers breached the marine lines multiple times. At one point, they came within a few hundred yards of Henderson Field itself. The outcome hung in the balance for hours. The marines were pushed back to their final defensive positions. If those positions fell, the airfield would be lost. But the marines held.

Edson personally rallied his men during the crisis, moving along the line under fire, directing counter-attacks, refusing to give ground. When Marines began to fall back under the weight of Japanese attacks, Edson stood in the open and shouted orders. The ridge, he told them. This is the ridge. Hold it.

Artillery fire called in by forward observers devastated the Japanese assault waves. The shells fell with deadly accuracy, breaking up Japanese formations before they could mass for decisive attacks. The coordination between the infantry on the ridge and the artillery batteries behind them was critical to survival.

When ammunition ran low, marines fought with bayonets and rifle butts. Hand-to-hand combat raged across the ridge as Japanese soldiers who had penetrated the lines were hunted down and killed. The night was filled with the sounds of grenades, the crack of rifle fire, and the screams of wounded men. At one point during the second night of fighting, Japanese soldiers got so close to Henderson Field that they could see the parked aircraft.

American personnel began preparing to destroy the planes rather than let them fall into enemy hands. It seemed that everything the Marines had fought for was about to be lost. Then the Japanese attack faltered. The combination of Marine resistance, artillery fire, and sheer exhaustion had broken Kawaguchi’s offensive. His men had given everything they had. It was not enough.

By dawn on September 14th, Kawaguchi’s attack had failed. More than six hundred of his men lay dead on the ridge, and in the jungle approaches. Hundreds more were wounded. The survivors retreated into the jungle, many of them starving, to begin a nightmare march westward that would kill hundreds more from disease, hunger, and exhaustion.

Vandegrift later said that Kawaguchi’s assault on the ridge was the only time during the entire campaign he had doubts about the outcome. If the Japanese had broken through, he admitted, we would have been in a pretty bad condition. Historian, Richard B. Frank would later write that the Japanese never came closer to victory on the island itself than in September 1942, on a ridge thrusting up from the jungle just south of the critical airfield, best known ever after as Bloody Ridge. The Marines had held. Again.

And this time, they had held against a force specifically designed to overwhelm them. The defeats of Ichiki and Kawaguchi should have forced a fundamental reassessment of Japanese assumptions. They did not. Japanese commanders escalated their commitment to Guadalcanal while refusing to acknowledge what the battles had revealed about American fighting capability.

The problem was systemic. Japanese military culture did not encourage honest reporting of failures. Officers who admitted that their plans had failed risked disgrace. It was easier to blame subordinates, bad luck, or unusual circumstances than to confront the possibility that fundamental assumptions were wrong.

So, instead of recognizing that the Marines were more capable than expected, Japanese commanders concluded that they simply needed more men, more ships, more resources. The basic approach was sound. The execution had been flawed. This time would be different. Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake, commander of the 17th Army, arrived on Guadalcanal on October 9th to personally oversee the next offensive. He brought with him the 2nd Sendai Division, one of the most illustrious units in the Imperial Japanese Army.

The Sendai had fought in Manchuria and China. They were veterans of campaigns that had proven Japanese superiority over Asian armies. Surely they would prove it again against Americans. This time there would be no half-measures.

Over 20,000 Japanese troops would participate in a coordinated assault that would finally overwhelm the American defenders. The attack would come from multiple directions simultaneously. Artillery support would be provided by naval vessels that would bombard Henderson Field before the assault. Air attacks would suppress American aviation.

Hyakutake was so confident of success that his staff prepared plans for accepting the American surrender. They discussed the ceremony in detail. They wanted it to be the envy of every unit in the Japanese army. There was no doubt in anyone’s mind that the Marines would be destroyed. The date selected for the final assault was October 23, 1942.

Hyakutake sent a message to his superiors that captured his confidence. The time of the decisive battle between Japan and the United States has come, he declared. He was right about that. But the battle would not go as he expected. The battle for Henderson Field, also called the October Offensive, began on the night of October 23, 1942.

Hyakutake launched attacks from multiple directions, attempting to overwhelm the marine perimeter through sheer weight of numbers. The first attacks came along the Matanikau River on the western side of the perimeter. Japanese tanks, nine or ten of them, clanked forward in the darkness, their engines audible before they came into view.

Marines with 37mm anti-tank guns waited until the tanks were close, then opened fire. One by one, the tanks were destroyed. Japanese infantry following the tanks were cut down by machine gun fire. But the main attack came from the south, where the Sendai division was supposed to achieve the decisive breakthrough. And at one section of that line, Sergeant John Basilone of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines commanded two sections of heavy machine guns.

Basilone was known as Manila John because he had served in the Army in the Philippines before joining the Marine Corps. He was 25 years old, born in Buffalo, New York, and raised in Raritan, New Jersey, the sixth of ten children in an Italian-American family. He had learned his craft during his army years and had become acknowledged as one of the outstanding experts on the.30 caliber machine gun in the Marine Corps.

Throughout the night of October 24th and 25th, his position was attacked by approximately 3,000 soldiers from the Sendai Division. The results were catastrophic for Japan. Bazalone fought through the night and into the next day without sleep, without food, without rest. When his ammunition ran low, he fought through enemy territory to bring back more, carrying ninety pounds of weapons and ammunition across two hundred yards of ground swept by Japanese fire.

When his gun crews were killed or wounded, he manned the weapons himself. When the machine guns jammed from the heat of continuous firing, he repaired them under fire, burning his hands on the superheated barrels. At one point, enemy bodies piled up so high in front of his position that they blocked his field of fire.

Marines had to leave their fighting positions to push the corpses aside so they could continue shooting. Private First Class Nash Phillips, who lost a hand during the battle, later described Bazalone visiting him at the medical tent. He was barefooted, and his eyes were red as fire. His face was dirty black from gunfire and lack of sleep.

His shirt sleeves were rolled up to his shoulders. He had a.45 pistol tucked into the waistband of his trousers. He had just dropped by to see how I was making out, me and the others in the section. I will never forget him. He will never be dead in my mind.

By the time reinforcements arrived, only Bazalone and two other marines from his section were still standing. The ground in front of their position was carpeted with Japanese dead. Bazalone would receive the Medal of Honor for his actions, becoming the first enlisted Marine to earn the award during World War II. Similar scenes played out across the Marine perimeter that night.

At another position, Lieutenant Colonel Lewis Chesty Puller commanded the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines. Puller would become the most decorated Marine in history, but on this night he was simply another officer trying to keep his men alive against overwhelming odds. His battalion held. So did the others.

The coordinated Japanese assault, the one that was supposed to finally overwhelm the American defenders, broke against the same determination that had defeated Ichiki and Kawaguchi. After the battle, Pula interrogated a Japanese prisoner. He asked a simple question. Why did you not change tactics when you saw you were not breaking our line? Why did you not shift to a weaker spot? The prisoner’s response revealed everything about why Japan kept failing on Guadalcanal. That is not the Japanese way, he said. The plan had been made.

No one would have dared to change it. It must go as it is written. This rigidity, this absolute commitment to predetermined plans regardless of circumstances, combined with the continuing underestimation of American fighting capability, proved fatal. The Japanese military system did not encourage initiative at lower levels.

Officers who modified plans risked disgrace. Soldiers who suggested alternatives to their superiors violated the chain of command. The Americans were different. Marine officers were trained to adapt. When situations changed, they changed with them. When one approach failed, they tried another.

This flexibility, combined with the stubborn refusal of individual Marines to give up their positions, created a defensive system that the Japanese could not break regardless of how many men they threw against it. The October offensive failed completely. Japanese casualties numbered between 2,200 and 3,000 dead. American casualties were fewer than 300 killed and wounded. The exchange rate was devastating.

The Sendai Division, one of the oldest and most distinguished units in the Japanese army, had been shattered. For the first time, Japanese commanders began to seriously consider the possibility that Guadalcanal could not be retaken. The forces they had committed, the resources they had expended, the lives they had sacrificed, had achieved nothing.

The Marines still held Henderson Field, the aircraft still flew, the perimeter still stood. As 1942 drew to a close, the situation on Guadalcanal had transformed completely. The island that Japanese commanders had expected to retake in days had become what their soldiers bitterly called Starvation Island.

It was a place where Japanese soldiers went to die, not from American bullets, but from disease, hunger, and despair. The Tokyo Express, the nightly destroyer runs that brought reinforcements and supplies, could not deliver enough to sustain the Japanese forces on the island. American control of Henderson Field meant that slow transport ships could not approach during daylight without being destroyed by aircraft.

Everything had to be brought in on fast warships that could make the run down the slot and escape before dawn. It was never enough. The drums and bags of supplies that destroyers threw overboard often floated away before starving soldiers could retrieve them. American air attacks sank supply ships. PT boats harassed the Tokyo Express.

Each night fewer supplies reached the troops ashore. Japanese soldiers resorted to eating roots, grass, and the bark of trees. They suffered malaria, dysentery, beriberi, and a host of tropical diseases that their medical system was unprepared to treat.

Men who had been strong warriors weeks before became walking skeletons, too weak to fight, too weak to retreat. They developed their own grim method of determining how long a man might survive on the island. He who can rise to his feet has thirty days left to live. He who can sit up has twenty days left. He who must urinate lying down has three days. He who cannot speak has two days.

He who cannot blink his eyes will be dead at dawn. They watched helplessly as American planes flew overhead from the airfield they had been unable to capture. They saw American ships delivering supplies to the Marines while their own forces starved.

They heard the sound of American artillery, American bombers, American machine guns, and they knew that everything their commanders had promised them was a lie. The psychological impact on Japan extended far beyond the soldiers dying in the jungle. For the first time in the Pacific War, Japanese forces had been fought to a standstill by Americans. For the first time, the myth of Japanese invincibility had cracked.

By December, the myth of Japanese invincibility, had cracked. By December, General Hyakutake was desperate. On December 23rd, he sent a message to Tokyo that captured the reality on the ground. No food available and we can no longer send out scouts. We can do nothing to withstand the enemy’s offensive.

17th Army now requests permission to break into the enemy’s positions and die an honourable death rather than die of hunger in our own dugouts. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the combined fleet, wrote to Vice-Admiral Gunichi Mikawa that the situation on Guadalcanal Island is very serious. Much more serious than that the Japanese confronted in the Russo-Japanese War when they had to occupy Port Arthur before the approach of the Baltic Fleet to far eastern waters. This was an extraordinary comparison.

The siege of Port Arthur in 1904 and 1905 had been one of the most difficult and costly campaigns in Japanese military history. For Yamamoto to compare Guadalcanal to that desperate struggle revealed how completely the campaign had exceeded all expectations. The Japanese eventually withdrew from Guadalcanal in early February 1943.

Operation K.E., as it was called, was one of the most successful evacuation operations of the war. Over three nights, Japanese destroyers spirited approximately 10,600 surviving troops off the island under the noses of American forces. They left behind over 14,000 dead from combat and another 9,000 who had perished from disease and starvation.

For every American killed on Guadalcanal, the Japanese lost nearly 10 men, and those who escaped were broken, many of them suffering from conditions that would never fully heal. Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi, the commander who had failed at Edson’s Ridge, had seen firsthand how the campaign had consumed Japan’s finest units.

He understood better than most what the losses meant for Japan’s future in the Pacific. He was not exaggerating. Guadalcanal had consumed some of Japan’s best units. The Sendai Division, the Ichiki Regiment, the Kawaguchi Brigade, all had been shattered against the marine defences. The pilots and aircrew lost in the air battles over the island were irreplaceable.

The ships sunk in the waters around Guadalcanal. In battles with names like Savo Island, the Eastern Solomons, Cape Esperance, and the naval battle of Guadalcanal, represented a hemorrhage of naval power that Japan could not sustain. But the most important loss was invisible. It was the destruction of a belief.

The Marines who fought on Guadalcanal had proven something that Japanese commanders had believed impossible. had proven something that Japanese commanders had believed impossible. Americans could fight. Americans could hold their ground. Americans could match Japanese ferocity and determination in close combat.

The spiritual superiority that was supposed to guarantee Japanese victory simply did not exist. This realization spread through the Japanese military establishment with devastating effect. In the Solomons, in New Guinea, in every subsequent campaign of the Pacific War, Japanese commanders would face opponents who would not break, would not surrender, and would not run. The tactical implications were profound.

Japanese commanders could no longer assume that aggressive night attacks would cause American lines to collapse. They could no longer count on spiritual superiority to overcome material disadvantages. They had to fight Americans as equals, and in that kind of fight, American industrial production and logistical superiority would prove decisive. The Marines themselves had not set out to disprove Japanese ideology.

They were simply doing what they had been trained to do. But in holding Henderson Field against repeated Japanese assaults, they had shattered one of the most dangerous assumptions in modern military history. The consequences would echo through every battle that followed. Major General Alexander Vandegrift received the Medal of Honor for his leadership on Guadalcanal.

The citation praised his tenacity, courage, and resourcefulness against a strong, determined, and experienced enemy. President Franklin Roosevelt presented the medal to him in a ceremony at the White House in February 1943. Vandegrift would later become the 18th Commandant of the Marine Corps and the first Marine to hold the rank of four-star general while on active duty.

Lieutenant Colonel Merritt Edson, who commanded the defence of Bloody Ridge, also received the Medal of Honour. His citation described how he repeatedly exposed himself to enemy fire to direct and encourage his men. The ridge itself bears his name to this day, a permanent memorial to the 800 Marines who held it against waves of Japanese attackers from Kawaguchi’s brigade.

Sergeant John Basiloni, the machine gunner who held his position against 3,000 Japanese soldiers, became a national hero. When he received the Medal of Honor, he said something that captured the spirit of the Marines on Guadalcanal. Only part of this medal belongs to me. Pieces of it belong to the boys who are still on Guadalcanal.

He was offered a commission and a stateside posting. Opportunities to sit out the rest of the war in safety while selling war bonds. He turned them down. He requested to return to combat. On February 19, 1945, he was killed on the first day of the invasion of Iwo Jima, while single-handedly destroying a Japanese blockhouse and then guiding a tank through a minefield under heavy fire.

He was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross, becoming the only enlisted Marine in World War II to receive both the Medal of Honor and the Navy Cross. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. The 1st Marine Division, the unit that had borne the brunt of the Guadalcanal campaign, was so ravaged by combat and disease that it had to be withdrawn from the Pacific for months of recovery. When the division was declared combat ready again, it went on to fight at Cape Gloucester, Peleliu, and Okinawa.

The word Guadalcanal appears on its shoulder patch to this day. The division’s nickname, the Old Breed, comes from the men who fought there. Today, that shoulder patch is a red numeral one on a blue diamond with the Southern Cross constellation, and the word Guadalcanal beneath it.

Every Marine who has served in the 1st Division since 1943 has worn that patch, a permanent reminder of what their predecessors accomplished on that jungle-covered island, but perhaps the most important legacy of Guadalcanal was invisible. It was the destruction of an idea, the belief that Japanese spiritual superiority could overcome any enemy. That belief had sustained Japanese military confidence for decades.

It had convinced Japanese planners that they could fight and win a war against the United States, despite vast disadvantages in industrial capacity and resources. Guadalcanal proved it false. The Marines did not win because they had better equipment. In many respects, their weapons were inferior to those of the Japanese.

The Zero Fighter was more maneuverable than American planes in the early months of the war. Japanese torpedoes were more reliable. Japanese night-fighting tactics were superior to anything the Americans possessed. They did not win because of numerical superiority. They were often outnumbered.

Ichiki attacked with 900 men against 11,000 marines, but Kawaguchi’s force was comparable to what the marines had available to defend the ridge. During the October offensive, the Japanese committed 20,000 men against a marine force that was not significantly larger. They did not win because of overwhelming firepower. Their supplies were limited throughout the campaign.

Artillery ammunition had to be rationed. Food was so scarce that marines lost weight throughout the battle. Medical supplies ran out. Everything had to be brought in by ship or plane through waters and skies contested by Japanese forces. They won because they fought.

They held their ground when doctrine said they should not be able to. They matched Japanese determination with their own. They demonstrated that the spiritual qualities Japanese commanders believed unique to themselves were present in equal measure on the other side of the battle line. Japanese military leaders had spent years convincing themselves that Americans were soft.

They believed that American democracy produced citizens who valued personal comfort over collective sacrifice. They believed that American materialism had corrupted the fighting spirit that all true warriors needed. They believed that when Americans faced the choice between death and surrender, they would choose surrender every time.

Guadalcanal proved them catastrophically wrong. The Marines who landed on Guadalcanal in August 1942 were mostly young men in their late teens and early twenties. Many had never been away from home before joining the Corps. They were sick, hungry, undersupplied, and operating without naval support for weeks at a time. They held an airfield against the most elite troops the Japanese Empire could send against them.

They did this not through some mysterious warrior spirit, but through discipline, training, and sheer stubborn refusal to give up. They did it because they were Marines. They did it because they were marines. They did it because their officers told them the ridge had to hold, and they believed it. They did it because the men next to them were counting on them not to run.

They did it because that was what they had signed up to do when they walked into those recruiting stations after Pearl Harbor. When Japanese commanders learned what their soldiers faced on Guadalcanal, they began to understand that the war they had started would not end the way they had planned. The Americans would not negotiate, they would not sue for peace.

They would fight, island by island, until Japan itself was threatened. Admiral Yamamoto had warned of this before the war began. In the first six to twelve months of a war with the United States and Great Britain, he had said, I will run wild and win victory upon victory, but then, if the war continues after that, I have no expectation of success.

Guadalcanal was where that prediction came true. The six months were over. The run of victories had ended. What remained was a grinding, brutal war of attrition that Japan could not win. The marines on Guadalcanal did not know they were changing history. They were simply trying to survive. They were fighting malaria and dysentery alongside the Japanese. They were living on captured rice and contaminated water.

They were losing friends every day to enemy fire and tropical disease. But in holding that airfield, in refusing to break, they demonstrated something that would shape the rest of the Pacific War. American Marines could fight. American Marines would not quit. And Japanese commanders who had built their entire strategy on the assumption that Americans lacked fighting spirit had been proven utterly wrong.

Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi understood this better than most. He had led the assault on Bloody Ridge. He had seen his men cut down by Marines who would not retreat. He had watched his carefully planned offensive collapse against defenders who matched Japanese determination with their own. After the war, when historians asked him to assess the campaign, he offered his verdict. Guadalcanal, he said, is the graveyard of the Japanese army.

He was right. Everything that came after, the island-hopping campaign across the Pacific, the fall of Saipan that brought American bombers within range of the Japanese homeland, the terrible battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, the atomic bombs that finally ended the war, all of it grew from seeds planted on a jungle covered island in the Solomons, where American marines proved that Japanese commanders had been wrong about everything. The Japanese military had spent decades preparing for war with the United

States. They had studied American culture. They had assessed American military capability. They had concluded that Americans lacked the will to fight. It took six months on Guadalcanal to destroy that assumption forever. Today, the battlefields of Guadalcanal are quiet. The jungle has reclaimed most of the fighting positions.

Rusted equipment and scattered bones occasionally surface when farmers plough their fields. The ridge where Edson’s men held against Kawaguchi’s brigade is peaceful now, covered in grass and tropical flowers. But the memory remains. In the Marine Corps, Guadalcanal is sacred ground. The men who fought there are honoured as the foundation of everything that came after.

The battles they won, often against impossible odds, established a reputation that would carry the Corps through the rest of the war and into the conflicts that followed. And in Japan, though the battle is less well remembered than in America, its significance is understood by those who study the war. Guadalcanal was where the tide turned.

Guadalcanal was where the myth of Japanese invincibility died. Guadalcanal was where everything changed. If you found this story compelling, please take a moment to like this video. It helps us share more forgotten stories from the Second World War. Subscribe to stay connected with these untold histories. Each one matters.

Each one deserves to be remembered. And we would love to hear from you. Leave a comment below telling us where you are watching from. Our community spans the globe, from veterans to history enthusiasts. You are part of something special here. Thank you for watching, and thank you for keeping these stories alive.

News

Tom Brady Is Reportedly Preparing Major “Heist” To Secure Highly-Coveted NFL Head Coach For His Las Vegas Raiders

Tom Brady Is Reportedly Preparing Major “Heist” To Secure Highly-Coveted NFL Head Coach For His Las Vegas Raiders January 7,…

New Details Emerge On Tense Meeting Between John Harbaugh & Ravens Owner Steve Bisciotti Before Shocking Firing

New Details Emerge On Tense Meeting Between John Harbaugh & Ravens Owner Steve Bisciotti Before Shocking Firing January 6, 2026,…

Japanese Pilots Laughed At The F6F Hellcat, Until It Swept Their Zeros From The Sky

Japanese Pilots Laughed At The F6F Hellcat, Until It Swept Their Zeros From The Sky Tanggal 1 September 1943, lapangan…

How Canadian Snipers Were So Precise the Germans Thought They Used Witchcraft

How Canadian Snipers Were So Precise the Germans Thought They Used Witchcraft November, 1943, Moro River, Valley, Italy. Captain Ernst…

Nazi POWs in Arizona Were Taken to the Grand Canyon – They Couldn’t Believe it Was Real

Nazi POWs in Arizona Were Taken to the Grand Canyon – They Couldn’t Believe it Was Real At 2.47 in…

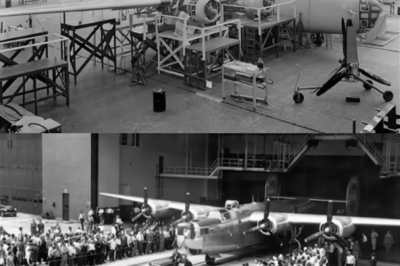

German Spies Were Shocked Ford Built A 1.5 Million Part Bomber Every 63 Minutes

German Spies Were Shocked Ford Built A 1.5 Million Part Bomber Every 63 Minutes March 17th, 1943. Terpitzufer, 76-78, Berlin….

End of content

No more pages to load