Why Delta Force HATES Training with the SAS

America’s most elite soldiers learned everything from the British SAS. Yet every year they secretly dread joint training that pushes them to quit, break, or fail in ways they never face at home. The story begins not with rivalry, but with admiration. In 1962, a young American officer embedded with the SAS and returned obsessed, spending 15 years fighting to create Delta Force in their image.

When tragedy struck at Operation Eagle Claw, the price of imperfection became death. If Delta Force owes its existence to the SAS, why is their training the one thing American operators still fear? And what does that reveal about the true cost of special operations excellence? In 1962, a young American special forces officer named Charles Beckwith arrived in Malaya to serve with the British Special Air Service, known as SAS.

For a year, he carried a heavy rucks sack across jungle and hillside, watching SAS candidates pushed to exhaustion and then left alone to find their way. No encouragement, no second chances, just quiet removal if they faltered. The experience rewired his view of what a truly elite unit could be. In his memoir, Beckwith described the SAS as a place where selection was silent, suffering was routine, and small teams made their own decisions deep behind enemy lines.

He returned to the United States, convinced that the army was missing something vital. A permanent national level force built on ruthless selection, relentless autonomy, and the expectation that operators could survive and succeed with little more than a map and their own judgment. For 15 years, Beckwith lobbyed generals and Pentagon officials facing repeated rejection.

The fear was always the same that such a unit would be too independent, too hard to control, or simply unnecessary. But Beckwith persisted, citing the rising threat of international terrorism and the proven record of the SAS. In 1977, after years of resistance, the Army finally approved his plan. Delta Force was born at Fort Bragg.

Its selection and structure lifted directly from the SAS blueprint. [music] The goal was clear. Create an American unit that could match the British in skill, resilience, and the ability to disappear into chaos and return with the mission complete. Yet, from the very beginning, that imitation carried a hidden tension. One that would surface every time the two units trained together.

April 1980, Operation Eagle Claw launched under the cover of darkness, aiming to rescue 52 Americans held hostage in Thran. Delta Force, still in its infancy, led the ground element. Eight helicopters set out across the Iranian desert, but mechanical failures in a sandstorm forced three to [music] turn back. At the remote staging site called Desert 1, confusion and exhaustion set in when a helicopter collided with a C130 refueling aircraft, a fireball erupted, killing eight American service members instantly. The mission was aborted,

leaving burned wreckage and stunned survivors behind. Images of charred machinery and lost lives were broadcast around the world. Pentagon investigators found the failure ran deeper than bad luck. There was no unified command, no dedicated special operations aviation, and no system for joint planning. The shock was immediate and public.

Congress demanded answers. Within months, the Department of Defense created the Joint Special Operations Command, JSOC, tasked with integrating elite units like Delta and the SAS into a single coordinated force. The 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment known as the Nightstalkers was established to provide the specialized air support Eagle Claw lacked. For Delta, the lesson was clear.

Even the most skilled operators are vulnerable without the right structure and allied expertise. Every painful training exchange with the SAS that followed carried the memory of that night in the desert and the price of getting it wrong. Breen beacons in winter SAS [music] candidates set out alone, each with a 60B Bergen and a paper map facing miles of ridge lines and bog.

The route is unmarked, the checkpoints sparse, and the only guidance is a compass. The standard is simple. Complete the march, sometimes 40 m in under 24 hours, or disappear from the course without acknowledgement. The pass rate rarely breaks 10%. [music] Instructors offer no encouragement, no time checks, and no hint of progress.

Those who fall behind are quietly returned to their units, often without a word. The silence is intentional. Success is met with the same restraint as failure. In contrast, Delta Force selection in the Appalachian Hills [music] demands similar endurance and navigation under load, but within a framework that includes structured feedback and periodic assessment.

Candidates receive some indication of standards and are observed not just for physical grit but for how they integrate with a team under stress. Where Delta assesses SAS breaks. The difference is felt from the first mile. One system isdesigned to build the other to strip away. Day three in the Scottish Highlands.

Rain seeps through every layer turning the ground to freezing mud. Delta Force operators huddle over their individual rations. Steam rising from chemical heaters while nearby SAS troopers crouch around a patch of wet grass. No tents, no stoves, no warm food. One British trooper pulls a rabbit from a snare, kills it with a practiced grip, and skins it with a dull blade.

They eat quickly, barely cooking the meat, hands raw and chapped. When the Americans offer spare rations and hot drinks, [music] the SAS wave them off. One mutters, “Comfort makes you soft.” For the Delta men trained to see logistics as a source of strength, it is a jarring lesson. The SAS do not just tolerate deprivation. They engineer it.

Assuming that in the field gear will be lost, resupply will fail, and technology will break. Every calorie denied, every hour spent cold and hungry is a rehearsal for the moment when nothing works. And survival depends on what you can find and what you can endure. The lesson is not about food.

It is about refusing to depend on anything you cannot carry or catch. For Delta, it is a philosophy that feels both alien and unsettling, [music] raising doubts about how much their own comfort has become a silent liability. A joint navigation challenge drops the American operators into the Welsh hills with nothing but a paper map, a compass, [music] and a strict order.

48 hours, no GPS, no radios, no checkpoints, absolute silence. For men used to satellite imagery and constant communications, the isolation is immediate. One Delta team, after hours of wandering through fog and bog, admits defeat and calls for emergency extraction. The SAS cadre barely blink. For them, getting lost is not a failure of skill.

It is a test of whether you can keep moving when everything familiar vanishes. The price for breaking the silence is not a lecture. It is a beasting. The entire group, Americans and British alike, are ordered into icy water and forced to churn out burpees and flutter kicks until muscles spasm and breath comes ragged.

In the SAS tradition, suffering is shared and anonymous. No one is singled out and there is no room for ego. Under US Army rules, this kind of collective punishment would trigger questions about hazing and legality. Here it is a right of passage. The pain is more than physical. It is a lesson. When the map runs out and the technology dies, only grit and humility get you home.

Delta operators cluster around a whiteboard, tracing every angle of entry, rehearsing the assault route for hours. Plans are dissected, contingencies mapped, every operator drilled on their exact movement. Night vision, flashbangs, live feeds, every tool is in play. When the signal comes, the American team clears the building with textbook precision.

Each room methodically dominated every threat accounted for across the compound. The SAS team gets 30 minutes. Their briefing is blunt, their prep minimal. On the signal, they surge forward, doors kicked in, rooms swept in a blur of speed and controlled violence. The entire clearance is over in seconds. In the postex exercise debrief, voices sharpen.

British instructors question the need for elaborate planning, arguing that realworld targets rarely wait for a perfect timeline. Delta counters, warning that unchecked aggression risks friendly fire and missed threats. The debate is immediate and unfiltered. Precision against aggression, process against instinct.

Both sides certain their way is the one that brings everyone home. British understatement and American morale culture meet in the field, not just the classroom. For the SAS, hardship is a source of quiet pride. Suffering is endured and not discussed, and camaraderie is built after the mission, never during. Americans, by contrast, are raised to see morale as a force multiplier with structured afteraction reviews and encouragement woven into daily life.

In Baghdad 2006, when a group of SAS operators found themselves pinned down by insurgent fire, it was Delta Force that delivered the supporting fire that allowed the British team to break contact and survive. Veterans from both sides recall that night as proof of a bond that runs deeper than rivalry. Over decades, each unit has borrowed from the other.

SAS adopting American night vision and precision gear. Delta integrating hard-learned lessons in survival and improvisation. The rivalry endures because it sharpens both. But when the bullets start flying, only trust and shared experience matter. When the world’s most elite units push each other past comfort, the lessons cut deeper than any rivalry.

In an age of technology, true resilience still means surviving when everything fails. That’s why this partnership endures and why its hardships matter more than ever. What would you endure?

News

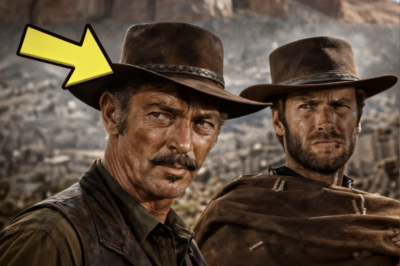

Lee Van Cleef Finally Tells the Truth About Clint Eastwood

Lee Van Cleef Finally Tells the Truth About Clint Eastwood Lee Vancliffe finally tells the truth about Clint Eastwood. Lee…

Arab Billionaire Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Don’t Belong Here’ — Instantly Regrets It!

Arab Billionaire Told Ozzy Osbourne ‘You Don’t Belong Here’ — Instantly Regrets It! When the doors of Leardam, one of…

John Ford Never Forgot the Way Lee Marvin Looked at John Wayne on The Hawaiian Beach After the Punch

John Ford Never Forgot the Way Lee Marvin Looked at John Wayne on The Hawaiian Beach After the Punch John…

Bikers Thought He Was Just Another Old Man — Then Realized It Was Ozzy Osbourne…

Bikers Thought He Was Just Another Old Man — Then Realized It Was Ozzy Osbourne… Picture this. A lonely gas…

WHAT JAPAN’S LEADERS ADMITTED When They Realized America Couldn’t Be Invaded

WHAT JAPAN’S LEADERS ADMITTED When They Realized America Couldn’t Be Invaded In the stunned aftermath of Pearl Harbor as Japanese…

Street Kid Playing “Mama, I’m Coming Home” When Suddenly Ozzy Osbourne Showed Up

Street Kid Playing “Mama, I’m Coming Home” When Suddenly Ozzy Osbourne Showed Up When the first notes of, “Mama, I’m…

End of content

No more pages to load