He Spent 42 Years on Death Row Waiting to Die — But When Death Finally Came, It Wasn’t by Execution. The Unbelievable End to South Carolina’s Longest-Serving Inmate’s Life Leaves Everyone Asking Why.

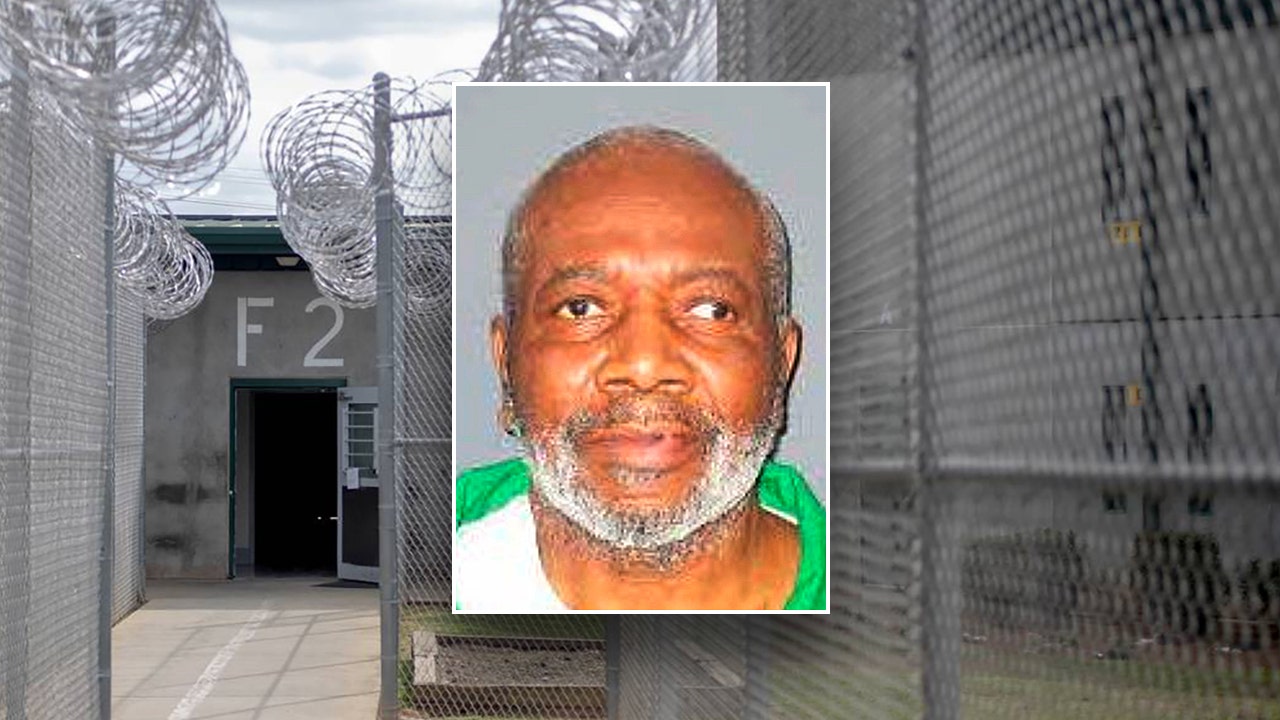

After spending more than four decades on South Carolina’s death row, Willie Lee Darden Jr., one of the nation’s longest-serving condemned inmates, has died — not by lethal injection, firing squad, or electric chair, but of natural causes at the age of 73.

For a man sentenced to die in 1983, the end came quietly inside a state prison infirmary, decades after the public had forgotten his name but long after his story had come to symbolize the endless, costly, and morally fraught machinery of America’s death penalty system.

A Death Delayed — and Then Denied

Prison officials at the South Carolina Department of Corrections confirmed that Darden died of complications related to heart disease on Friday morning at the Broad River Correctional Institution, the same maximum-security facility where he had spent nearly half his life.

“He was alert the night before, but by morning, he was gone,” said a corrections spokesperson. “There was no foul play. Just time catching up.”

For many, the news reignited a haunting question: How can a man sentenced to die spend 42 years waiting for a punishment that never comes?

Convicted, Condemned, and Forgotten

Darden was 23 years old when he was convicted of murder and armed robbery in a 1982 convenience store killing that shocked rural Florence County. Prosecutors argued the crime was brutal and unprovoked; the jury needed less than two hours to recommend the death penalty.

But in the years that followed, Darden’s case became entangled in a maze of appeals, retrials, and procedural stays — reflecting the broader collapse of confidence in capital punishment nationwide.

Over time, his lawyers argued that key evidence had been withheld and that racial bias tainted the original trial. New attorneys took up his case in the 1990s and 2000s, but each time execution neared, last-minute motions, appeals, or questions about the state’s lethal injection drugs postponed the inevitable.

The Long Shadow of Death Row

South Carolina has not carried out an execution since 2011, due in part to the state’s inability to obtain lethal injection drugs after pharmaceutical companies began restricting their use in executions.

The state legislature authorized firing squads and electric chairs as alternative methods, but those changes became mired in lawsuits and constitutional challenges.

As a result, men like Darden remained in a strange legal limbo — sentenced to death but not executed, effectively serving life terms under the shadow of a punishment the state could not legally or logistically carry out.

“It’s a paradox,” said Dr. Angela Foster, a criminal justice scholar at the University of South Carolina. “Death row becomes not a place of punishment but of suspension — a purgatory that raises profound ethical questions about justice, mercy, and human endurance.”

A Life Reduced to Waiting

Prison records show that Darden maintained a quiet routine for decades: reading, writing letters to his sister, and occasionally painting landscapes from memory.

He became something of a fixture among the newer inmates — an elder statesman of a decaying system. “He’d seen guards come and go, wardens retire, even other inmates die,” said one former prison chaplain. “He used to say the hardest part wasn’t dying — it was waking up every day not knowing if it would finally happen.”

Despite being largely forgotten by the outside world, Darden’s story drew renewed attention in 2023, when advocacy groups began highlighting “America’s aging death row” problem — an emerging crisis in which inmates are outliving both their sentences and their execution protocols.

The Cost of Waiting for Death

Over his 42 years in custody, taxpayers spent an estimated $2.3 million to house, guard, and provide medical care for Darden — nearly six times the average cost of imprisoning a non-death row inmate for the same period.

Critics of the death penalty say his case exposes the system’s moral and fiscal contradictions.

“If the state cannot or will not carry out executions, then continuing to sentence people to death is an illusion of justice,” said Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative. “It creates suffering without closure, punishment without purpose.”

An Unanswered Question

In the end, Darden’s death came not from the state’s hand but from nature’s. No family members claimed his body as of Monday, and prison officials said he would be buried in a state cemetery near Columbia.

But even in death, his case remains a mirror — reflecting a justice system still struggling with its conscience.

“He went into that cell expecting to die in months,” said a former defense attorney who worked on one of his appeals. “Forty-two years later, the state still hadn’t figured out how to kill him. Maybe that says everything.”

A Legacy of Silence

As South Carolina continues to debate the future of capital punishment, Willie Darden’s story stands as both tragedy and testimony — a life consumed by waiting, a death that raises more questions than answers.

For a man sentenced to die, his passing came not with violence, but with quiet inevitability — leaving behind one final, unspoken truth:

Sometimes the system runs so long, it forgets what it was built to do.

News

🚨 BREAKING: Pam Bondi reportedly faces ouster at the DOJ amid a fresh debacle highlighting alleged incompetence and mismanagement. As media and insiders dissect the fallout, questions swirl about accountability, political consequences, and who might replace her—while critics claim this marks a turning point in ongoing institutional controversies.

DOJ Missteps, Government Waste, and the Holiday Spirit Welcome to the big show, everyone. I’m Trish Regan, and first, let…

🚨 FIERY HEARING: Jasmine Crockett reportedly dominates a Louisiana racist opponent during a tense public hearing, delivering sharp rebuttals and sparking nationwide attention. Social media erupts as supporters cheer, critics react, and insiders debate the political and cultural impact, leaving many questioning how this showdown will shape her rising influence.

Protecting Individual Rights and Promoting Equality: A Congressional Debate In a recent session at Congress, members from both sides of…

🚨 ON-AIR DISASTER: “The View” hosts reportedly booed off the street after controversial prison comments backfired, sparking public outrage and media frenzy. Ratings reportedly plunge further as social media erupts, insiders scramble to contain the fallout, and critics question whether the show can recover from this unprecedented backlash.

ABC’s The View continues to struggle with declining ratings, and much of the blame is being placed on hosts Sunny…

🚨 LIVE COLLAPSE: Mrvan’s question, “Where did the data go?”, reportedly exposed Patel’s “100% confident” claim as false just 47 seconds later, sparking an intense on-air meltdown. Critics and insiders question credibility, accountability, and transparency, as the incident sends shockwaves through politics and media circles alike.

On March 18, 2025, during a House Judiciary Committee hearing, Congressman Frank Mirvan exposed a major FBI data security breach….

🚨 LIVE SHOCKER: Hillary Clinton reportedly reels as Megyn Kelly and Tulsi Gabbard call her out on live television, sparking a viral political confrontation. With tensions high, viewers are debating the fallout, insiders weigh in, and questions arise about Clinton’s response and the potential impact on her legacy.

This segment explores claims that the Russia investigation was allegedly linked to actions by the Hillary Clinton campaign during the…

🚨 MUST-SEE CLASH: Jasmine Crockett reportedly fires back at Nancy Mace following an alleged physical threat, igniting a heated public showdown. Social media explodes as supporters rally, critics debate, and insiders warn this confrontation could have major political and personal repercussions for both parties involved.

I’m joined today by Congresswoman Jasmine Crockett to discuss a recent clash with Republican Congresswoman Nancy Mace during the latest…

End of content

No more pages to load