U-530: The Ghost Submarine That Surrendered at the End of the World

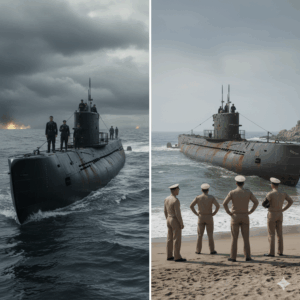

At dawn on July 10, 1945, the fishermen of Mar del Plata awoke to a sight that seemed torn from the last chapter of a spy novel. A massive gray silhouette broke the stillness of the South Atlantic horizon — a German U-boat, running on the surface, white flag raised, heading straight for Argentina’s main naval base.

It had been more than two months since Germany’s unconditional surrender ended World War II in Europe. Most surviving U-boats had long since surfaced, transmitting their positions and surrendering at Allied ports across the globe. Yet here was U-530, Type IXC/40, sliding silently into the harbor like a ghost from a war that should have been over.

Its appearance would spark international headlines, Allied investigations, conspiracy theories that refuse to die — and a mystery that has never been fully solved.

The Last Patrol

U-530 had a long and active combat history, but its final patrol would be its most controversial. The submarine had departed Horten, Norway, on March 3, 1945, with a young and ambitious commander at the periscope: Oberleutnant Otto Wermuth, just 24 years old. This was his first command, and he had inherited a boat still in fighting shape, carrying 22 torpedoes and a crew of over 50.

The orders were simple: disrupt Allied shipping in the western Atlantic. But by spring 1945, the war was all but lost. Allied air cover blanketed the North Atlantic, and convoys were heavily defended. Wermuth stalked the lanes near Halifax and later off New York, but success eluded him. Between May 4 and May 7, U-530 fired nine torpedoes — all missed. These would be the last offensive shots the boat ever fired.

On May 8, the radio brought the message that changed everything: Admiral Karl Dönitz had ordered all U-boats to cease hostilities and surrender.

For most crews, this was a bitter but clear directive. Dozens surfaced and surrendered within days. But Wermuth hesitated. He later testified that he feared the message might be a trick — or that surrendering in an Allied port could lead to brutal imprisonment, or even execution.

In that moment, he made a decision that would define his legacy. He ordered U-530 to turn south — toward Argentina.

The Rogue Voyage

The journey that followed was as grueling as it was secretive. U-530 ran submerged during the day, using its snorkel to recharge batteries, and surfaced at night to make better speed. Wermuth ordered strict radio silence, except for brief weather reports.

Bit by bit, the crew shed the tools of war. Torpedoes were jettisoned, except for one damaged round. Codebooks, cipher machines, and the ship’s log were dumped overboard. Even the deck gun had been removed earlier in the war.

“Everything that could be of value to the enemy — gone,” one surviving crewman reportedly told interrogators later.

The voyage lasted over two months, a feat of endurance for men packed in steel tubes with dwindling rations. They crossed the equator in mid-June, taking care to remain unseen. When land finally appeared on the horizon, the men were gaunt, exhausted, and unsure of the welcome that awaited them.

The Surrender at Mar del Plata

In the predawn darkness of July 10, 1945, U-530 surfaced one final time. The crew raised a white flag and turned on their navigation lights as they approached Mar del Plata.

Argentine naval sentries were stunned. One reportedly had his back to the sea and missed the boat’s approach entirely. By the time the alarm was raised, the submarine was already inside the harbor.

Captain Wermuth signaled his intention to surrender. Within hours, Argentine sailors boarded the U-boat, disarmed the crew, and took all 54 men ashore. They were fed, shaved, and placed under guard. The boat itself became a prized trophy, moored at the pier, surrounded by curious onlookers.

But the questions came quickly.

The Interrogations

Argentine officers noted that U-530 had no torpedoes, no logbook, no personal papers. When asked why the voyage had taken so long, Wermuth offered only vague answers. He first claimed the engines had failed, then admitted he had sabotaged them himself — pouring acid into the cylinders to ensure the boat could not be reused.

To Argentine investigators, this sounded suspiciously like a cover-up.

Within days, the news reached Allied command. Argentina, which had only declared war on Germany in March 1945, was pressured to turn over the boat and its crew. Soon Wermuth and his men found themselves interrogated by both Argentine and American officers.

Repeatedly, they denied carrying passengers, cargo, or fugitives. “We landed no one, we carried no one,” Wermuth insisted.

Yet doubts lingered. If U-530 had simply obeyed the surrender order late, why destroy the log? Why take such a long, roundabout route?

Rumors and Legends

The absence of hard facts left a vacuum — and conspiracy theories rushed to fill it.

Some newspapers claimed U-530 had landed Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun on the remote Patagonian coast before surrendering. Others accused the boat of sinking the Brazilian cruiser Bahia just days before arriving in Argentina.

Historians and investigators eventually debunked these claims. Bahia was determined to have exploded accidentally during gunnery practice. And no credible evidence has ever placed Hitler anywhere but dead in his Berlin bunker.

Still, the timing — and the mystery — kept the story alive. Five weeks later, another U-boat, U-977, arrived in Argentina after a similar rogue voyage, fueling suspicions of a larger plot.

The Aftermath

By late July, U-530’s crew was transferred to U.S. custody. The boat itself was towed north to the Panama Canal and eventually brought to the East Coast as a war prize. In the fall of 1945, curious Americans toured the captured submarine as part of a naval exhibition.

For Wermuth and his men, the war ended not in death or glory, but in captivity. They spent nearly two years as prisoners before being repatriated to Germany in 1947. None were charged with war crimes.

U-530’s final fate came that same year. The U.S. Navy selected the boat for use as a live-fire target. On November 20, 1947, off Cape Cod, the American submarine USS Toro fired a torpedo that split U-530 in two and sent it to the bottom.

It was an unceremonious end for a vessel that had traveled so far to survive.

The Legacy of U-530

Today, U-530 remains one of naval history’s strangest footnotes. Its story is often retold in documentaries, books, and online forums. For some, it is proof of a daring escape attempt, perhaps even the last flicker of a Nazi plan for a “Fourth Reich” abroad. For most historians, it is a tale of a young commander choosing flight over surrender — and prolonging the war for himself and his men long after it had ended.

In the words of one Allied intelligence report from 1946:

“No evidence has been found to suggest that U-530 carried passengers or contraband. Her late arrival in Argentina was due to deliberate evasion of the surrender order by her commanding officer.”

And yet, the very lack of a complete logbook means the truth can never be fully known.

Perhaps that is why the story endures. U-530 is not just a submarine — it is a symbol of the war’s chaotic final days, when loyalty, fear, and survival instincts collided on every front.

As for Captain Wermuth, he lived quietly after the war, seldom speaking of the voyage that made him infamous. For him, the ending was not a mystery, only a memory of a decision made under the weight of defeat.

For the rest of the world, U-530 will always be the submarine that refused to surrender — until it had crossed an entire ocean.

News

🚨 BREAKING: Pam Bondi reportedly faces ouster at the DOJ amid a fresh debacle highlighting alleged incompetence and mismanagement. As media and insiders dissect the fallout, questions swirl about accountability, political consequences, and who might replace her—while critics claim this marks a turning point in ongoing institutional controversies.

DOJ Missteps, Government Waste, and the Holiday Spirit Welcome to the big show, everyone. I’m Trish Regan, and first, let…

🚨 FIERY HEARING: Jasmine Crockett reportedly dominates a Louisiana racist opponent during a tense public hearing, delivering sharp rebuttals and sparking nationwide attention. Social media erupts as supporters cheer, critics react, and insiders debate the political and cultural impact, leaving many questioning how this showdown will shape her rising influence.

Protecting Individual Rights and Promoting Equality: A Congressional Debate In a recent session at Congress, members from both sides of…

🚨 ON-AIR DISASTER: “The View” hosts reportedly booed off the street after controversial prison comments backfired, sparking public outrage and media frenzy. Ratings reportedly plunge further as social media erupts, insiders scramble to contain the fallout, and critics question whether the show can recover from this unprecedented backlash.

ABC’s The View continues to struggle with declining ratings, and much of the blame is being placed on hosts Sunny…

🚨 LIVE COLLAPSE: Mrvan’s question, “Where did the data go?”, reportedly exposed Patel’s “100% confident” claim as false just 47 seconds later, sparking an intense on-air meltdown. Critics and insiders question credibility, accountability, and transparency, as the incident sends shockwaves through politics and media circles alike.

On March 18, 2025, during a House Judiciary Committee hearing, Congressman Frank Mirvan exposed a major FBI data security breach….

🚨 LIVE SHOCKER: Hillary Clinton reportedly reels as Megyn Kelly and Tulsi Gabbard call her out on live television, sparking a viral political confrontation. With tensions high, viewers are debating the fallout, insiders weigh in, and questions arise about Clinton’s response and the potential impact on her legacy.

This segment explores claims that the Russia investigation was allegedly linked to actions by the Hillary Clinton campaign during the…

🚨 MUST-SEE CLASH: Jasmine Crockett reportedly fires back at Nancy Mace following an alleged physical threat, igniting a heated public showdown. Social media explodes as supporters rally, critics debate, and insiders warn this confrontation could have major political and personal repercussions for both parties involved.

I’m joined today by Congresswoman Jasmine Crockett to discuss a recent clash with Republican Congresswoman Nancy Mace during the latest…

End of content

No more pages to load