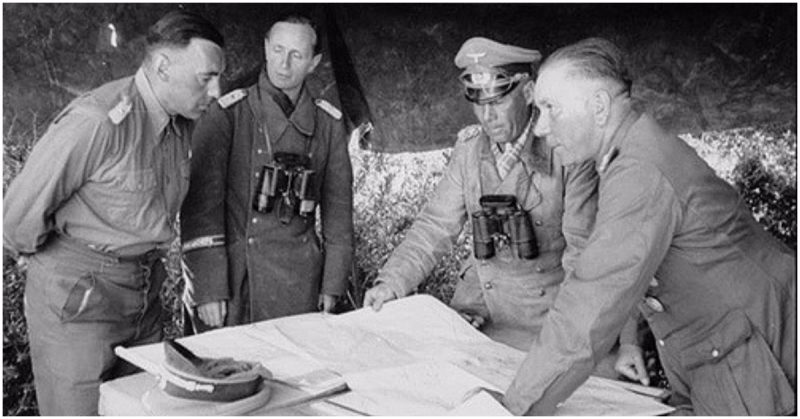

The Collapse of Panzer Lehr: General Bayerlein and the Normandy Catastrophe

On the morning of July 25, 1944, General Fritz Bayerlein found himself crouched amid the ruins of his forward command post. For forty relentless minutes, Allied bombers had shaken the ground beneath him, detonating explosions that set fields ablaze and sent his Panthers up in flames. The Panzer Lehr Division, Germany’s elite demonstration unit, which had trained countless other formations, was vanishing—not due to enemy tanks or brilliant battlefield maneuvers, but because of an invisible force from the skies. There was nothing Bayerlein could do to stop it; he could only watch as his men and machines were systematically destroyed.

The day had begun with a sense of cautious optimism. At 06:50, Bayerlein stood outside his command post, a reinforced farmhouse near Marigny, surveying the breaking clouds. For weeks, weather conditions had shielded his division from the relentless Allied air assaults. Now, that protection was lifting, revealing the danger he had long feared: complete vulnerability to enemy air power. Bayerlein, a man of meticulous strategy, had survived campaigns in Poland, France, Russia, and North Africa by anticipating enemy moves and neutralizing them through superior positioning and tactical ingenuity. But by July 1944, even his expertise was powerless.

Panzer Lehr had been committed to Normandy as a reserve armored force, but over the past month, it had been eroded in place. Every German attack faltered, every maneuver was interrupted, and every position was eventually overrun by an enemy with seemingly endless resources. When the division left Chartres on June 7 with 316 tanks, it represented a formidable force. By late July, only 93 tanks remained operational, fuel stocks were dwindling, ammunition was scarce, and repair facilities had collapsed. The professional soldiers who had made Panzer Lehr a showcase division were being ground down by the unrelenting Allied pressure.

Hopes rose briefly with the launch of Operation Cobra. The plan called for Panzer Lehr and other reserves to strike the American right flank, sealing off the breakout. If executed perfectly, it might have driven a wedge into the advancing American forces. Bayerlein clung to the possibility, despite the deterioration of his division. But at 08:30, the first wave of P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers arrived. They came in massive formations, dropping rockets and bombs with terrifying precision. Concussion waves rattled the earth, trees were uprooted, and centuries-old hedgerows vanished. The bombardment was relentless, mechanical, and devastating.

Radio operators relayed catastrophic reports: entire battalions wiped out, Panthers overturned by near misses, fuel depots ablaze, and forward command posts obliterated. By 11:00, Bayerlein could assess the scale of the disaster. Forward battalions that had begun with hundreds of men and dozens of tanks were reduced to shock-stricken fragments, scattered across the battlefield. Ammunition and supply lines were destroyed, and repair facilities were nothing more than rubble.

No German air support arrived to counter the bombing. The Luftwaffe had abandoned Normandy weeks earlier, leaving Bayerlein’s division completely exposed. The systematic annihilation continued with B-17 Flying Fortresses targeting rear positions, dropping thousands of kilograms of bombs over the devastated landscape. By 14:00, after ninety minutes of relentless bombardment, the sky fell silent. When Bayerlein attempted to reestablish contact with his units, the reports were harrowing: 2,500 men lost and only seven operational Panthers scattered across an 8-kilometer front. The division that had started the day with 93 tanks now had seven.

Even tactical brilliance could not counter the industrial might of the Allies. The remaining Panthers, superior in armor and firepower to the Sherman tanks, were impotent against the logistical avalanche behind them. American infantry advanced through the cratered terrain with disciplined coordination, supported by endless waves of tanks and supplies. Each Sherman destroyed was quickly replaced, while every Panther lost was irreplaceable. The mathematics were devastating: Germany had produced approximately 6,000 Panthers in total during the war, while American factories were producing 4,500 Shermans per month. Allied industrial capacity, combined with strategic bombing that destroyed German production lines, ensured that German losses were permanent while American replacements arrived in abundance.

By August 1, Panzer Lehr was officially withdrawn from the front. Its remaining vehicles were cannibalized for parts, its soldiers scattered to other units, and the division’s elite status was irreparably lost. Though technically reconstituted later, the new units lacked the experience, training, and equipment that had made Panzer Lehr formidable.

In that shattered farmhouse on July 25, Bayerlein confronted a stark truth: modern warfare was no longer merely about courage, skill, or tactical brilliance. It was about systems—industrial capacity, logistical networks, and relentless production. The war in Normandy was not lost on the battlefield alone; it had been lost long before, in factories, refineries, and assembly lines. By the end of that day, with seven tanks remaining and 2,500 men dead or wounded, Bayerlein realized that the industrial supremacy of the Allies had rendered even the most elite German formations powerless.

News

The Truth About Jessica Tarlov Is Finally Coming to Light — and It’s Raising Serious Questions

This transcript appears to be from a biographical video or article profiling Jessica Tarlov, a political commentator and co-host of…

Inside the 300,000 Newly Released Epstein Files: The Celebrity Photos Raising Alarming Questions | Elizabeth Vargas Reports

The provided text appears to be a partial transcript from a News Nation broadcast discussing the recent release of Jeffrey…

Erika Kirk Allegedly Caught in Yet Another Lie — Conflicting Claims About Charlie Kirk’s Texts That “Predicted” His Murder Raise Alarming Questions

This transcript is another monologue by Jimmy Dore, focusing on the ongoing controversy surrounding Charlie Kirk’s 2022 murder, Candace Owens’…

Shapiro & Bari Weiss Take Shots at Megyn Kelly — Her Explosive Clapback Steals the Show!

This is the same transcript from Jimmy Dore’s monologue as in the previous query. Since no new content or reasoning…

Shapiro & Bari Weiss Take Shots at Megyn Kelly — Her Explosive Clapback Steals the Show!

This is the same transcript from Jimmy Dore’s monologue as in the previous query. Since no new content or reasoning…

CH2. LEGAL EARTHQUAKE: MICHELLE OBAMA’S $100M CASE AGAINST SEN. KENNEDY CRASHES DOWN WHEN ONE WITNESS UNLEASHES A 9-SECOND TRUTH NUKE

LEGAL EARTHQUAKE: MICHELLE OBAMA’S $100M CASE AGAINST SEN. KENNEDY CRASHES DOWN WHEN ONE WITNESS UNLEASHES A 9-SECOND TRUTH NUKE Michelle…

End of content

No more pages to load