1964: R*cist Cops Called Bumpy Johnson N word, what happens next is.. – YouTube

It was 3:47 p.m. on Tuesday, September 15th, 1964, when officers Patrick Sullivan and James Kowalsski, both assigned to the 28th precinct covering Harlem, walked into the Palm Cafe on 125th Street, where Bumpy Johnson was sitting at his usual corner table, conducting afternoon business over coffee and cigars with several associates.

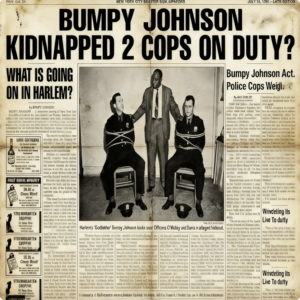

The two white officers moved directly to Johnson’s table, badges visible, hands resting on their service weapons in the universal police posture of authority backed by potential violence. Bumpy Johnson. Sullivan announced loudly enough that everyone in the cafe could hear clearly. You’re under arrest for operating an illegal gambling operation, for conspiracy to distribute narcotics, and for assaulting a police officer during questioning last week.

Stand up, put your hands behind your back, and come with us to the precinct. Now, according to seven witnesses who were present in the Palm Cafe that afternoon and who spoke with the Harlem Gazette between September 16th and September 18th, 1964, Johnson looked up at the two officers with an expression somewhere between amusement and contempt, made no move to stand up, and asked a single question that made clear he knew exactly what was happening.

Which paycheck came in this week, Sullivan? Did Vincent Jagante pay you, or was it someone from city hall? Sullivan’s face flushed red with anger, insulting Bumpy Johnson with racial slur and calling him all sort of names, while, according to witnesses, Sullivan grabbed Johnson’s arm and tried to pull him out of his chair forcibly.

But Johnson remained seated, his considerable weight and strength making it impossible for Sullivan to move him without assistance from Kowalsski. Resisting arrest, Sullivan said, “That’s another charge.” Kowalsski helped me get this criminal out of his chair and into the squad car. What happened next, according to all seven witnesses, was one of those moments that changes the trajectory of events completely.

That transforms what should have been a routine, if corrupt, arrest into a confrontation that would shake the NYPD to its foundations within 72 hours. Detective Marcus Thompson, 38, one of the few black detectives working out of the 28th precinct, walked into the Palm Cafe at precisely 3:49 p.m. 2 minutes after Sullivan and Kowalsski had attempted to arrest Johnson, apparently having been tipped off by someone in the precinct that Sullivan and Kowalsski were planning an arrest and that their arrest might not be legitimate.

Officers, what’s the basis for this arrest? Thompson asked in a voice loud enough that everyone in the cafe heard him clearly. Sullivan turned toward Thompson, his hand still gripping Johnson’s arm. This doesn’t concern you, detective. We’re executing an arrest warrant on charges of gambling, narcotics, and assault.

Thompson walked closer, positioning himself between Sullivan and the door. Show me the warrant and show me the incident report about the alleged assault on a police officer last week that you just cited as one of the charges. According to witnesses, Sullivan and Kowalsski exchanged glances that suggested they hadn’t expected to be questioned by another officer about the legitimacy of their arrest.

“The warrant is back at the precinct,” Kowalsski said. We can show it to you after we bring Johnson in. That’s not how arrests work, Officer Kowalsski, Thompson responded. You need to have the warrant with you when you execute it, or you need to have probable cause for an arrest without a warrant. What’s your probable cause? What evidence do you have that Mr.

Johnson committed the crimes you just alleged he committed? The cafe had gone completely silent. Everyone present understood they were witnessing something extraordinary. A black detective openly challenging two white officers about an arrest in Harlem, demanding they justify their actions, refusing to simply defer to their authority because of their race and their seniority.

Sullivan released Johnson’s arm and turned his full attention to Thompson. Listen, detective. I don’t know what you think you’re doing here, but you’re interfering with a legitimate arrest. You need to leave this cafe and let us do our jobs. I’m doing my job, Thompson said calmly. My job is to ensure that arrests are legal and properly documented. You’ve alleged Mr.

Johnson assaulted a police officer last week. Which officer? When did this assault occur? Where’s the incident report? Where’s the officer who was allegedly assaulted? Why wasn’t Mr. Johnson arrested immediately after the assault occurred rather than a week later? According to witnesses, Sullivan’s face had gone from red to purple with rage.

You’re going to regret this, Thompson. You’re protecting a known criminal. I’m protecting the law, Thompson interrupted. The law requires that you have either a warrant or probable cause. You’ve shown me neither. You’ve made allegations without evidence. You’ve attempted to physically remove Mr.

Johnson from this establishment without legal justification. That’s not a legitimate arrest. That’s kidnapping under color of authority. So, here’s what’s going to happen. You’re going to release Mr. Johnson. You’re going to leave this cafe. And if you believe you have legitimate charges against Mr. Johnson, you’re going to go back to the precinct.

You’re going to get a properly signed warrant from a judge, and you’re going to return with that warrant and with proper documentation. Until then, Mr. Johnson is free to go about his business. Sullivan stared at Thompson for approximately 10 seconds. long enough that witnesses thought Sullivan might try to arrest Thompson along with Johnson.

But finally, Sullivan stepped back from Johnson’s table. “This isn’t over,” Sullivan said, pointing at Johnson. “We’ll be back with a warrant with everything properly documented, and then you’re going downtown, and your pet detective won’t be able to protect you.” Sullivan and Kowalsski walked toward the door, but Johnson’s voice stopped them before they could exit.

Sullivan, Kowalsski, you tell Vincent Jagante and whoever else is paying you that this will not be finished until I decide it’s finished. You understand? This isn’t over. Not by a long shot. The two officers left without responding, and the cafe remained silent for several seconds after they’d gone. Then Johnson stood up, walked over to Detective Thompson, and shook his hand.

“Thank you, Marcus,” Johnson said quietly. “You didn’t have to do that. Could cost you your career.” Thompson shrugged. “Could, but I didn’t become a cop to watch other cops break the law. Those two are dirty. Everyone in the precinct knows they’re dirty. Someone needed to stop them.” Johnson nodded. I won’t forget this.

If you ever need anything, anything at all, you call me. Understood? Understood, Thompson said. Then he lowered his voice so only Johnson could hear according to what Thompson later told the Gazette. Bumpy, be careful. Sullivan and Kowalsski work for Vincent Gigante. Everyone in the precinct knows it, but nobody says it out loud.

They’re going to come back with fabricated evidence and a friendly judge who’ll sign whatever warrant they want. You stop them today, but they’re not going to stop coming after you.” Johnson smiled slightly. “Let them come. I’ve got plans for Sullivan and Kowalsski. By the time I’m done with them, they’re going to wish they’d never heard my name.

” James Kowalsski left the 28th precinct at 11:15 p.m. on Wednesday, September 16th, 1964, 24 hours after the failed arrest attempt at the Palm Cafe, and walked to his car parked two blocks away on 126th Street. According to the official missing person’s report filed by Kowalsski’s wife on Thursday morning, Kowalsski never made it home that night.

His car was found the next morning, still parked on 126th Street, undamaged, no signs of struggle. What the official report didn’t mention, but what three witnesses who worked for Bumpy Johnson later described to the Gazette was that Kowalsski was approached by four men as he reached his car. men who identified themselves as working for Johnson and who politely but firmly suggested that Kowalsski accompany them to a meeting with Mr.

Johnson to discuss Tuesday’s arrest attempt. “The men made clear that Kowalsski had a choice,” says William Bub Hewlet, Johnson’s chief of security, speaking with the Gazette on September 17th, 1964. He could come voluntarily for a conversation or he could be forced to come. Either way, Mr. Johnson wanted to talk to him about who’ paid him to arrest Mr.

Johnson and about what other corrupt activities Officer Kowalsski had been involved in during his years working in Harlem. Kowalsski chose to come voluntarily, which was smart on his part. Kowalsski was taken to an empty warehouse in the Bronx outside NYPD’s immediate jurisdiction and far enough from Harlem that any screaming wouldn’t attract attention from people who might recognize Kowalsski or care about what was happening to him.

According to Hulet, Johnson was waiting in the warehouse when Kowalsski arrived. Mr. Johnson explained the situation to officer Kowalsski very clearly. Hulet recounts. Mr. Johnson said, “You tried to arrest me on Tuesday on fabricated charges. I want to know who paid you to do it. I want to know how much they paid you.

I want to know what other corrupt activities you’ve engaged in. And I want you to write down the names of every other cop in the 28th precinct who’s taking bribes. You’re going to write all of that down in your own handwriting, and you’re going to sign it. and then we’re going to have a discussion about what happens next.

According to Hulet, Kowalsski initially refused, claiming he’d done nothing wrong and demanding to be released, but Johnson’s associates made clear that refusal wasn’t an option. Kowalsski could write the information voluntarily, or he could be encouraged to write it through methods that would be unpleasant but notpermanently damaging.

After about 30 minutes of discussion and some physical persuasion, Officer Kowalsski decided cooperation was his best option, Hulet says delicately. He wrote for approximately 2 hours, producing a detailed confession about his own corrupt activities and a list of 23 other officers in the 28th precinct who he knew were taking money from Vincent Jaganti’s organization.

The list included names, approximate amounts of bribes received, and what services the cops were providing in exchange for the money, primarily protection for Gigante’s gambling operations and harassment of Gigante’s competitors, which included Mr. Johnson. Kowalsski signed his confession and his list, was kept in the warehouse under guard, and was told he’d be released once Johnson had verified the information.

and had collected similar information from his partner, Officer Patrick Sullivan. Patrick Sullivan left his home in Queens at 6:05 a.m. on Thursday morning, September 17th, 1964, driving toward the 28th precinct for his shift that was scheduled to begin at 7 coo. According to his wife’s later testimony to investigators, Sullivan had been nervous all day Wednesday after Kowalsski failed to come home Tuesday night, had talked about taking sick leave until the situation with Kowalsski was resolved, but had ultimately decided that failing to show up for work would

make him look guilty of something. Sullivan never reached the 28th precinct. His car was found abandoned on the Triber Bridge at approximately 8:30 a.m. Doors unlocked, keys still in the ignition, no signs of struggle. What investigators didn’t learn until much later was that Sullivan had been stopped at a police checkpoint on the Triber Bridge.

a checkpoint that consisted of four men dressed in police uniforms operating what appeared to be a legitimate roadblock to check for outstanding warrants and vehicle violations. Sullivan had shown his police identification, expecting to be waved through as fellow officers always waved each other through such checkpoints. Instead, he’d been asked to step out of his vehicle for irregularities in his vehicle registration, had been surrounded by the four officers, and had been informed that he was being detained on orders from Bumpy Johnson. Officer

Sullivan was taken to the same warehouse where Officer Kowalsski was being held, Hulet explains. Mr. Johnson greeted Sullivan personally and explained the same thing he’d explained to Kowalsski. You’re going to tell me who paid you to arrest me. You’re going to tell me about your corrupt activities.

You’re going to write down the names of every corrupt cop you know. And then we’re going to decide what happens to you and your partner based on how cooperative you are. Sullivan reportedly was less cooperative than Kowalsski initially, claiming he was a decorated officer with 15 years of service. that kidnapping a police officer was a crime that would send Johnson to prison for life, that the entire NYPD would be searching for him and would show no mercy when they found who’d taken him.

Johnson’s response, according to Hulet, who was present during the conversation, was calm and direct. Officer Sullivan, the NYPD doesn’t care about you as much as you think they do. You’re a corrupt cop who takes bribes from Vincent Chagante. Your superiors know you’re corrupt. Your fellow officers know you’re corrupt.

The only reason you haven’t been arrested yourself is because corruption is so widespread in the NYPD that investigating you would require investigating dozens of other cops who are doing exactly what you’re doing. So don’t threaten me with the NYPD coming to rescue you. The NYPD is going to be more interested in covering up your corruption than in rescuing you from the consequences of that corruption.

Now, you can write down what I’ve asked you to write down, or my associates can encourage you to write it down through methods that will be unpleasant for you. Your choice. After what Hulet describes as several hours of discussion and physical persuasion, similar to what Kowalsski had experienced, Sullivan began writing.

His confession was even more detailed than Kowalsski’s. Sullivan had been on Vincent Gigante’s payroll for nearly eight years, had received approximately $60,000 of dollars in total bribes during that time, had provided services including advanced warning about raids, protection for Gigante’s gambling operations, harassment of competitors to Gigante’s operations, and fabrication of evidence to arrest people Gigante wanted arrested.

Sullivan also wrote about receiving smaller payments from a city councilman named Robert Hayes, who’d paid Sullivan and other officers to provide security for illegal card games that Hayes ran in his district and to ignore building code violations at properties Hayes owned. Sullivan’s list of other corrupt officers over overlapped substantially with Kowalsski’s list, but included additional names that Kowalsskiapparently hadn’t known about.

Combined, the two lists identified 47 officers in the 28th precinct out of approximately 120 total officers assigned to that precinct who were taking regular bribes, primarily from Vincent Jagante’s operations, but also from other sources, including local politicians and smaller criminal operators.

The lists were devastating, says Theodore Green, Johnson’s attorney, who reviewed the confessions after they were completed. 47 corrupt cops in a single precinct, names, dates, amounts of money, specific corrupt acts, all written in the officer’s own handwriting and signed by them. The confessions specifically named Vincent Jagante as the primary source of corruption money not vague references to organized crime but specific identification of Gigante by name.

They also named Councilman Hayes and a few other politicians. If those lists became public, it would be the biggest police corruption scandal in New York history. It would destroy the reputation of the NYPD. It would force investigations that would bring down not just the 47 named officers, but also their supervisors who’d allowed the corruption to flourish.

And it would create massive problems for Vincent Gigante and the politicians named in the confessions. At 2:15 p.m. On Friday, September 18th, 1964, approximately 40 hours after Officer Kowalsski disappeared, and 32 hours after Officer Sullivan disappeared, Bumpy Johnson walked into the 28th precinct headquarters carrying a leather briefcase accompanied by his attorney, Theodore Green, and by two bodyguards who positioned themselves near the entrance while Johnson approached the front desk.

I’m here to see Captain Morrison, Johnson told the desk sergeant. Tell him Bumpy Johnson would like to discuss the current whereabouts of officers Patrick Sullivan and James Kowolski and would like to discuss certain irregularities in police conduct that have come to Mr. Johnson’s attention recently. According to the desk sergeant’s later testimony, the precinct headquarters went absolutely silent when Johnson made this announcement.

Every officer present understood immediately that Johnson was connected to the disappearances of Sullivan and Kowalsski and that Johnson was bold enough or crazy enough to walk directly into the precinct to discuss those disappearances with the precinct captain. Captain Robert Morrison, 52, emerged from his office within two minutes, accompanied by Detective Lieutenant Frank Chen, 45, who supervised detective operations in the precinct.

Both men looked at Johnson with expressions that combined anger, fear, and grudging respect for Johnson’s audacity in appearing at the precinct while two of Morrison’s officers were missing and presumably in Johnson’s custody. Mr. Johnson, Morrison said coldly, “You’re either the bravest man in Harlem or the stupidest.

Come into my office now. Your attorney can accompany you. Your bodyguards stay in the lobby.” Johnson, Green, Morrison, and Chen went into Morrison’s office and closed the door. According to Green, who recounted the conversation to the Gazette on September 18th, the meeting began with Morrison making threats and demands. Where are my officers, Johnson? What have you done with Sullivan and Kowalsski? If they’ve been harmed, I swear to God, I’ll have you arrested for kidnapping and assault on police officers and every other charge I can

think of. You’ll spend the rest of your life in prison. Now tell me where they are and tell me now. Johnson opened his briefcase, removed two handwritten documents, the confessions and lists that Sullivan and Kowalsski had written, and place them on Morrison’s desk. “Your officers are safe,” Johnson said calmly, according to Green’s account.

They’re being held in a secure location where they’re being treated well, where they’re being fed regularly, where they’re not being tortured or abused beyond what was necessary to encourage them to write these confessions. I’ll release both officers unharmed within 24 hours after you and I reach an understanding about certain matters.

Morrison picked up the documents, began reading them, and his face went white as he realized what he was looking at. “These are handwritten confessions,” Johnson continued. “Written by Sullivan and Kowalsski in their own handwriting and signed by them.” The confessions describe in detail their corrupt activities over the past 8 years, how much money they’ve received from Vincent Jagante, what illegal services they’ve provided in exchange for that money, and the names of 47 other officers in this precinct who are also taking bribes.

Sullivan also confessed to taking money from city councilman Robert Hayes for providing protection and ignoring code violations. I have the original signed confessions in a safe location. What you’re reading are copies. If anything happens to me, if I’m arrested, if I’m harmed, if I have any problems with police harassment going forward, those original confessions get delivered tothe New York Times, to the Daily News, to the Amsterdam News, and to the FBI.

Within 24 hours of publication, this precinct will be destroyed. 47 officers will be arrested. Vincent Giganti will face federal racketeering charges based on documented evidence of corrupting police officers. Councilman Hayes will be forced to resign and possibly face prosecution. Captain Morrison and Lieutenant Chen will be investigated for either participating in the corruption or for gross negligence in failing to stop corruption that involved nearly 40% of the officers under your command.

The NYPD’s reputation will be devastated. Public trust in police will collapse. And I will make sure that everyone knows the corruption scandal started because two of your officers, Sullivan and uh Kowalsski, tried to arrest me on fabricated charges on Tuesday, September 15th, because Vincent Gigante paid them to harass me.

Morrison stared at Johnson, the confessions still in his hands, clearly struggling to process what he was being told. Lieutenant Chen leaned over to read the documents over Morrison’s shoulder, his own face showing shock as he recognized the names of officers he’d worked with for years and saw Vincent Gagante’s name mentioned repeatedly throughout the confessions.

“This is extortion,” Morrison said finally. “You’re trying to blackmail the NYPD.” “No,” Johnson corrected. I’m offering the NYPD an opportunity to avoid a scandal that would destroy this department. I don’t want money. I don’t want favors. I want one very simple thing. I want to be left alone. I want corrupt cops who are on Vincent Gigante’s payroll to stop harassing me on behalf of their employer.

I want to conduct my business without police interference that isn’t legitimate law enforcement, but is actually competitive harassment paid for by Gigante, who can’t compete with me fairly, so he’s using corrupt cops as weapons against me. Johnson paused. Let that sink in, then continued. According to Green’s account, here’s the deal I’m offering.

I release Sullivan and Kowalsski unharmed. they return to duty. You conduct no investigation into their disappearances. You accept their story that they took unauthorized leave for personal reasons. And you discipline them with suspensions, but not with termination. In exchange, you ensure that I am not harassed by police going forward.

Legitimate investigations based on actual probable cause are fine. I understand that’s part of doing business in my line of work, but fabricated arrests, planted evidence, harassment paid for by Vincent Jagante or by politicians who don’t like that I won’t work with them, that stops immediately. If it doesn’t stop, if I continue to experience police harassment from corrupt officers working for Gigante, then these confessions get published and everyone named in them gets destroyed.

Vincent Jagante’s name appears 43 times in these confessions. 43 times officers describe receiving money from him, taking orders from him, harassing his competitors on his behalf. That documentation goes to federal prosecutors and Gigante faces charges that could send him to prison for 20 years.

Do you think Jagante wants that? Do you think the 47 officers named in these confessions want that? Do you think Captain Morrison wants to explain to the police commissioner why nearly 40% of officers under his command were corrupt and he never noticed? That’s the deal. Take it or spend the next year dealing with the biggest corruption scandal in NYPD history.

According to Green, Morrison and Chen sat in silence for approximately 2 minutes, reading and rereading the confessions, occasionally looking at Johnson with expressions that combined hatred and helpless recognition that Johnson held all the leverage in this negotiation. Finally, Morrison spoke.

If we agree to this, and I’m not saying we’re agreeing to anything, how do we know you won’t publish these confessions anyway? How do we know you won’t use them to blackmail us for future favors? Because I don’t want ongoing conflict with the NYPD, Johnson responded. Conflict is expensive and distracting and bad for business.

I want stability. I want to operate my businesses without police harassment. If you give me that stability, I have no reason to publish confessions that would create chaos that would hurt everyone, including me. But if you don’t give me that stability, if corrupt cops continue harassing me on behalf of Vincent Gagante, then I have every reason to publish the confessions because the chaos they create can’t be worse than the harassment I’m already experiencing.

Your choice, Captain Morrison. Peace or war. Stability or scandal? What’s it going to be? Morrison looked at Chen. Chen looked at the confessions, saw Vincent Jagante’s name mentioned repeatedly, saw the names of officers they’d worked with for years, saw documentation that could destroy careers and send people to federal prison.

Both men understood they had no good options,only a choice between bad options and catastrophic options. “Where are Sullivan and Kowalsski?” Morrison asked quietly. They’ll be released tomorrow morning at 81 a.m. at the corner of 125th and Lennox, Johnson said, unharmed. They’ll tell you they were held by unknown parties who questioned them about police corruption and who released them after completing their questioning.

You’ll accept that story without investigating further. Do we have an understanding? Morrison stood up, walked to his window, looked out at Harlem for a long moment, then turned back to Johnson. “We have an understanding,” Morrison said, his voice barely above a whisper. Sullivan and Kowalsski get released unharmed.

We don’t investigate their disappearances. And you don’t experience harassment from corrupt officers going forward. But Johnson, if you ever try something like this again, if you ever kidnap another officer, if you ever threaten this department again, I will personally destroy you, regardless of what lists you publish or what scandals you create.

Do you understand me? Johnson stood up, extended his hand to Morrison. Morrison stared at the hand for several seconds before reluctantly shaking it. I understand perfectly, Captain Johnson said. And I hope you understand that I meant every word I said. One more fabricated arrest. One more incident of harassment from cops on Jagante’s payroll.

One more time that officers under your command try to arrest me on behalf of Vincent Jagante or some politician who doesn’t like me. Those confessions get published within hours and this whole precinct comes down. Vincent Jagante’s name gets sent to federal prosecutors with documentation that he’s been corrupting police officers for years.

Peace or war, Captain Morrison, I’m offering peace. I suggest you take it. Johnson Green and the two bodyguards left the 28th precinct at 2:47 p.m. According to witnesses in the precinct lobby, every officer watched Johnson leave in complete silence, understanding that they just witnessed something unprecedented.

a criminal walking into police headquarters, admitting he’d kidnapped two officers and walking out free because the criminal held leverage that the police couldn’t counter. Officers Patrick Sullivan and James Kowalsski were released at the corner of 125th Street and Lennox Avenue at 8:03 a.m. on Saturday, September 19th, 1964. exactly where and when Bumpy Johnson had promised they’d be released.

Both men were unharmed beyond bruises consistent with the physical persuasion that had encouraged them to write their confessions. Both men immediately reported to the 28th precinct where they were debriefed by Captain Morrison and Lieutenant Chen. According to the official report filed by Morrison, Sullivan, and Kowalsski claimed they’d been kidnapped by unknown parties who’d questioned them about police corruption, who’d forced them to write confessions and lists of corrupt officers, and who’d released them after obtaining the information they wanted.

The official report made no mention of Bumpy Johnson, made no connection between the kidnappings and the failed arrest attempt on Tuesday, September 15th, and concluded that the kidnappers identities remained unknown and that investigation was ongoing. The unofficial reality known to everyone in the 28th precinct, but never spoken aloud, was that Bumpy Johnson had kidnapped two officers who’ tried to arrest him on fabricated charges paid for by Vincent Jagante, had extracted confessions that could destroy the

precinct and create federal problems for Jagante if made public, and had forced the NYPD to negotiate rather than retaliate because the alternative was a scandal that would devastate the entire department and expose Jagante to federal prosecution. Sullivan and Kowalsski were suspended for 30 days without pay for unauthorized absence from duty, but faced no criminal charges and returned to active duty in late October 1964.

According to multiple sources within the precinct, both officers were warned by Captain Morrison that any future corrupt activities would result in immediate termination and possible prosecution, and that the informal protection they’d enjoyed from supervisors who’d overlooked their corruption was permanently withdrawn.

After September 1964, Sullivan and Kowalsski were the most honest cops in the 28th precinct, says Detective Marcus Thompson. They’d learned that corruption had consequences, that Bumpy Johnson was more dangerous than Vincent Gigante when Johnson decided to fight back, that their supervisors wouldn’t protect them if they got caught again.

Both officers served out their remaining years on the force doing legitimate police work and both retired in the early 1970s without further incident. Fear is a powerful motivator for reform when fear is applied properly. The confessions that Bumpy Johnson extracted from Sullivan and Kowalsski and the threat to publish those confessions if police harassmentcontinued fundamentally changed how the NYPD operated in Harlem for the remainder of the 1960s.

officers who’d been taking regular bribes from Vincent Gigante to harass Johnson’s operations either stopped taking the bribes or stopped providing the harassment. Understanding that Johnson now had documentation that could destroy them and could create federal problems for Gigante if they continued their corrupt activities.

After September 1964, Bumpy experienced significantly less police harassment, says Green. There were still legitimate investigations when Johnson’s activities warranted them, still arrests when police had actual probable cause. But the pattern of fabricated arrests, planted evidence, and harassment for hire by corrupt cops working for Vincent Gagante that stopped almost completely after September 1964.

The 47 officers named in the confessions understood that Bumpy had their names, had documentation of their corruption, and would use that documentation if they gave him reason to. More importantly, they understood that the confessions specifically named Vincent Gigante 43 times, that publishing those confessions would expose Gigante to federal prosecution, and that Gigante wouldn’t protect officers who’d created that exposure by continuing to harass Johnson after being warned to stop.

Vincent Jagante, who in September 1964 was one of the most powerful figures in the Genevese crime family, reportedly learned about the confessions within days of Johnson’s meeting with Captain Morrison. According to underworld sources, Gigante was furious that Sullivan and Kowalsski had written confessions naming him specifically rather than using vague references that couldn’t be traced directly to him.

Gigante understood immediately that Johnson had outmaneuvered him, says a source who worked in Gigante’s organization and who spoke to the Gazette on condition of anonymity. Jagante had been using corrupt cops to harass Johnson’s operations for years, trying to damage Johnson’s business through police pressure without having to engage in direct gang warfare.

But Johnson turned that strategy against Gagante by documenting it and threatening to expose it publicly in ways that would create federal problems. Gaganti couldn’t retaliate against Johnson without confirming everything in the confessions. He couldn’t continue using corrupt cops to harass Johnson because that would trigger publication of the confessions.

Gigante was trapped by his own strategy, and Johnson was the one who trapped him. Captain Morrison reportedly conducted quiet internal investigations of several officers named in the confessions, forcing some into early retirement and transferring others to precincts outside Harlem where they’d have less opportunity for corruption.

But Morrison never conducted the sweeping public investigation that the confessions warranted because such an investigation would have confirmed everything Johnson had alleged and would have created the very scandal that Morrison was trying to avoid by negotiating with Johnson. Morrison was trapped too, explains Detective Thompson.

He knew 47 officers in his precinct were corrupt, had written confessions proving it, but couldn’t investigate publicly without destroying his own career and the department’s reputation. So he managed the problem quietly, forcing the worst offenders into retirement, warning others that future corruption would result in termination, tightening supervision to make corruption more difficult.

It wasn’t the comprehensive reform that Harlem deserved, but it was better than the complete corruption that had existed before September 1964. The confessions themselves, which remained in Johnson’s possession until his death in 1968, provided remarkable documentation of how Vincent Jagante had systematically corrupted police operations in Harlem during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

According to people who saw the confessions, they detailed a network of 47 corrupt officers taking regular payments from Gigante, ranging from $50 per month for beat cops to $500 per month for senior officers. Systematic protection of Gigante’s gambling operations with corrupt officers providing advanced warning about raids and arresting competitors on fabricated charges.

specific instances where officers had planted evidence, fabricated witness statements, and perjured themselves in court to secure convictions of people gigante wanted imprisoned names and amounts for smaller bribes paid by politicians, including Councilman Robert Hayes, who’d paid officers to ignore code violations and provide security for illegal card games.

The whole the confessions were extraordinary historical documents, says Green. They showed exactly how corruption worked, who was corrupt, how much corruption cost, what corrupt officers did to earn their bribes. If those confessions had been published in 1964, they would have completely changed public understanding of policecorruption in New York.

But Johnson kept them secret because they were more valuable as leverage than as published evidence. The threat of publication kept 47 officers honest and kept Vincent Jagante from using police harassment against Johnson. That was worth more than any scandal the confessions could have created. The confessions were destroyed after Johnson’s death from a heart attack in July 1968.

An explicitly natural death that required no investigation and that therefore triggered no publication of the confessions according to Johnson’s instructions. Family members reportedly burned the original documents to ensure they couldn’t be used against anyone. After Johnson was gone, Bumpy took the confessions to his grave.

Sega got says Hulet. He’d used them to protect himself for four years from September 1964 until July 1968. During those four years, police harassment of Johnson’s operations dropped dramatically because corrupt officers understood Johnson had documentation that could destroy them. When Johnson died of natural causes, there was no need to publish the confessions anymore, so they were destroyed. But their legend lived on.

The list that named Vincent Jagante 43 times. The list that named 47 corrupt cops. the list that brought the NYPD to its knees and forced them to negotiate with a criminal because the criminal had better documentation of police corruption than internal affairs had ever collected. In Harlem today, elderly residents who remember September 1964 still tell the story of the week Bumpy Johnson kidnapped two corrupt cops, extracted confessions that named Vincent Jagante and 47 other corrupt officers walked into police headquarters to

negotiate while still holding the kidnapped officers and walked out free because the police understood Johnson’s leverage was stronger than their authority. The story has been told and retold for decades, becoming legend, becoming the definitive example of Bumpy Johnson’s intelligence. His ability to gather information that became weapons to understand that documentation properly deployed could defeat institutions and criminals that seemed far more powerful than any individual.

September 1964 showed what Bumpy understood better than Vincent Jaganti understood, better than the NYPD understood, says Green. Power isn’t about violence or intimidation or having more soldiers than your enemies. Power is about leverage. Bumpy didn’t beat Vincent Gagante and the NYPD by shooting people or threatening families.

He beat them by documenting Gigante’s corruption of police officers and threatening to expose it publicly in ways that would destroy everyone involved. Those confessions, naming Gigante 43 times, were more powerful than any army could be because they threatened Gigante with federal prosecution. And they threatened the NYPD with the biggest scandal in its history.

That double threat, destroying both Gigante and the police simultaneously, gave Johnson leverage that neither Gigante nor the NYPD could counter. They had to negotiate. They had to give Johnson what he wanted because the alternative was destruction for everyone. Two corrupt cops tried to arrest Bumpy Johnson on September 15th, 1964. paid by Vincent Jaganti to harass Johnson on fabricated charges.

By September 19th, 1964, those two cops had been kidnapped, had written confessions naming Jagante 43 times, and naming 47 other corrupt officers, had been released unharmed, and had watched their boss negotiate with the man they’ tried to arrest because that man now held documentation that made him untouchable.

Vincent Gigante, one of the most powerful criminals in New York, learned that corrupting police officers left paper trails when the officers got caught and decided confessing was better than whatever Bumpy Johnson’s associates were threatening to do to them. The NYPD learned that tolerating corruption created vulnerabilities that smart criminals could exploit by documenting the corruption and threatening to expose it.

And Bumpy Johnson proved once again that intelligence beats authority when you understand what leverage is and how to use it properly. That was the meaning of September 1964. That was the list that named names. That was the weak documentation became more powerful than guns.

News

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word Dean Martin had…

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later Hong Kong,…

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory In 1943, the Chinese economy…

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office July 5th, 1945. Harry…

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene The coffee cup was…

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING June 18th, 1957,…

End of content

No more pages to load