A 7-Year-Old White Girl Wrote Ali “I WISH YOU WERE MY DAD” in 1973—His Response Changed Laws

The envelope was pink construction paper folded and sealed with what looked like an entire roll of tape. Muhammad Ali’s secretary sorting through hundreds of letters in September 1973 almost threw it away. But something stopped her. Maybe the crayon. Maybe the careful way it was sealed. Like the sender had used every piece of tape they could find.

Maybe the return address written so small she almost missed it. Sarah Miller, St. Joseph’s Home for Children, Rockford, Illinois. She placed it on top of Ali’s pile. This one’s from a kid. Might be sweet. Ali opened it that afternoon after training. Inside was a single piece of paper, also pink, with more crayon writing.

The message was short, just five sentences. But those five sentences would change Ali’s life, expose one of the darkest failures of the American child welfare system, and ultimately lead to legislative reform. in three states. Before we continue with the story, you can support us by subscribing to the channel and liking the video.

Don’t forget to write in the comments where you’re watching from and how old you are. Let’s continue. The letter said, “Dear Muhammad Ali, my name is Sarah. I am 7 years old. I live in a place for kids with no moms or dads. I wish you were my dad because you are brave and you stand up for people. Can you come get me?” Love, Sarah. Ali read it three times.

Then he called his secretary back. This letter. Do we know anything about this kid? Just what’s on the envelope? An orphanage in Rockford. Call them. Find out about Sarah Miller. Find out why she wrote to me. Muhammad, you get letters from kids all the time. Not like this. Ali interrupted. Something’s wrong.

I can feel it. A 7-year-old doesn’t write, “I wish you were my dad to a stranger unless something’s very wrong.” What Olly didn’t know was that Sarah Miller’s letter wasn’t supposed to reach him at all. It was supposed to be confiscated by staff at St. Joseph’s home for children.

Like all the other letters the children tried to send, the orphanage had strict rules, no unauthorized communication, no letters out without approval, no contact with anyone who might ask questions. But Sarah had been clever. She’d given her letter to a volunteer, a college student who came once a week to read to the children. The volunteer, not knowing the rules, had promised to mail it, and she had.

That single act of kindness would expose a child trafficking ring, bring down an orphanage, send seven people to prison, and force three state legislatures to completely overhaul their child welfare systems. But on September 14th, 1973, all Ali knew was that a 7-year-old girl needed help.

And Muhammad Ali wasn’t going to ignore her. Ali’s secretary called St. Joseph’s. The next morning, she asked to speak with Sarah Miller, saying Mr. Ali had received her letter and wanted to respond. The woman who answered was silent for a long moment. Then, I’m sorry, but we don’t have anyone here by that name. Are you sure? The letter came from your address.

We have strict privacy policies regarding our residence. I cannot confirm or deny. She’s 7 years old. Ali’s secretary interrupted. She wrote a letter to Muhammad Ali. He just wants to write back. As I said, we have policies. I cannot discuss individual children. The woman hung up. When his secretary reported back, Ali’s reaction was immediate. They’re lying.

They have that girl and they don’t want me to know about her. Why? Maybe privacy laws. No, Ali said firmly. The 7-year-old writes me a letter saying, “Come get me, and they claim she doesn’t exist. Something’s wrong. Give me an address. I’m going there. St. Joseph’s Home for Children was a three-story brick building on the outskirts of Rockford, Illinois, about 90 mi northwest of Chicago.

On paper, it was a respectable institution housing approximately 40 children at any given time. The stated mission was to provide temporary care until permanent homes could be found. But St. Joseph’s had a secret. A secret that Sarah Miller had accidentally threatened to expose with her pink crayon letter. Muhammad Ali arrived at St.

Joseph’s on September 20th, 1973, unannounced. He brought two people, his photographer Howard Bingham, and family lawyer Patricia Wells. Ali had learned that bringing a lawyer to places that didn’t want questions was usually smart. The woman at the front desk nearly fell out of her chair when Muhammad Ali walked through the door.

I’m here to see Sarah Miller, Ali said pleasantly. She wrote me a letter. I want to meet her. The woman stammered. I You can’t just We have procedures. Then let’s follow them, Patricia Wells said, stepping forward. We’d like to speak with your director now. Within minutes, a man emerged. 50s expensive suit that seemed out of place in a state-f funed orphanage.

His name was Douglas Fletcher, director of St. Joseph’s. Mr. Tr Fletcher said, extending his hand with a smile that didn’t reach his eyes. One unexpected honor. I’m afraid there’s been somemisunderstanding. No misunderstanding, Ali interrupted. I got a letter from Sarah Miller. She’s 7 years old. She lives here.

I want to see her. Fletcher’s smile faltered. Mr. Ali, we have very strict confidentiality policies regarding our residence. I’m not at liberty to Is she here or not? Ali asked. I cannot confirm or deny the presence of any specific child. That’s a yes, Ali said. If she wasn’t here, you just say we don’t have anyone by that name.

But you’re hiding behind policy, which means she’s here and you don’t want me to see her. Why? Fletcher’s face reened. Mr. Ali, I understand you’re a celebrity and you’re used to getting your way, but this is a private facility. You can’t just walk in and demand to see residents. If you don’t leave immediately, I’ll call the police. Patricia Wells pulled out a business card. Please do.

And when they arrive, we’ll explain that we have evidence a child in your care sent a distress letter to a public figure and you’re refusing to confirm her welfare. I’m sure the police and the press will find that very interesting. Fletcher stared at the lawyer for a long moment. Then he said quietly, “Follow me.” They walked through the building.

It was clean but sterile. institutional. The walls were gray. The floors were lenolium. There were no pictures, no decorations, nothing that suggested children lived here. Just long hallways with number doors. Where are the children? Olly asked. In their scheduled activities, Fletcher replied, tursly. The answer was rehearsed. Practiced.

It sounded like something from a brochure. Fletcher led them to a small office on the second floor. Wait here. I’ll see if Sarah is available. He left, closing the door behind him. Something’s wrong, Howard Bingham whispered. Did you see this place? It’s like a prison. Worse than a prison, Patricia Wells said. This place feels like nobody’s paying attention.

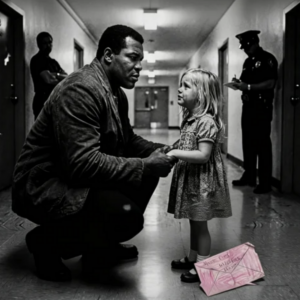

They waited 20 minutes. Then the door opened and a small girl walked in, followed by Fletcher. She had blonde hair and uneven pigtails, a faded dress that was too big for her, and eyes that were simultaneously hopeful and terrified. “Sarah,” Ali said gently, the girl nodded. “I’m Muhammad Ali. You wrote me a letter.

” Sarah’s eyes widened. “You came?” “Of course I came. You asked me to.” Fletcher cleared his throat. “You have 5 minutes. I’ll be right outside.” Actually, Patricia Wells said, “You’ll stay here in the room where we can see you.” Fletcher looked like he wanted to argue, but sat in the corner, arms crossed, watching. Ali knelt down, so he was at Sarah’s eye level. “Tell me about your letter.

Why did you write to me?” Sarah looked at Fletcher nervously. The director’s presence clearly scared her. “It’s okay,” Ali said softly. “You can tell me anything. I promise. I saw you on TV,” Sarah said. her voice barely audible. You said you stand up for people who can’t fight for themselves. And I thought, maybe you could stand up for me.

Stand up for you how? What’s happening? Sarah’s eyes filled with tears. They take us away. Who takes you away? Where? The people who come. They take kids and we never see them again. And I’m scared I’m next. Fletcher stood up abruptly. That’s enough. This child is confused. She doesn’t understand. Sit down, Ali said.

And his voice was no longer gentle. It was the voice he used before fights. The voice that said, I will destroy you if you push me. Fletcher sat. Olly turned back to Sarah. Tell me what happens. Tell me everything. And Sarah did haltingly at first, then faster, like a damn breaking. She told him about the people who came at night.

well-dressed couples who would tour the facility, look at the children like they were shopping, and then choose one. That child would be taken away immediately, no chance to say goodbye. Staff would say they’d been adopted, but it happened too fast. No paperwork that the children ever saw, just gone.

She told them about the kids who disappeared and were never mentioned again. About how staff threatened anyone who asked questions. about how she tried to run away twice and been locked in a room without food for 2 days as punishment. She told him that two days ago a couple had looked at her for a long time. And when couples did that, kids disappeared within a week.

By the time Sarah finished, Ali’s hands were shaking. Not from Parkinson’s. The symptoms weren’t pronounced yet in 1973, but from rage. He looked at Fletcher. What is she talking about? the confused fantasies of a traumatized child. Don’t, Ali said quietly. Don’t lie to me. Not right now.

Not when I’m trying very hard not to do something I’ll regret. Fletcher’s face had gone white. Mr. Ali, I think it’s time for you to leave. I’m not going anywhere without her. You have no legal right. Then I’ll get a legal right. Ali said. He turned to Patricia Wells. What do we need to do? The lawyer was already making notes.

Emergency protective custody. We need to prove immediate danger. We need evidence. Theevidence is right here, Ali said, gesturing to Sarah. A child’s testimony isn’t enough. We need documentation. Proof of wrongdoing. Ollie looked at Sarah. Do you have any proof? Any evidence of what you told me? Sarah thought for a moment.

Then she said, Jenny kept a list. Who’s Jenny? She was my friend. She was 11. She disappeared two months ago, but before she left, she wrote down the names of all the kids who disappeared. She had the paper in the bathroom under the sink behind the pipe. Olly stood. Show me. Fletcher blocked the door. Absolutely not.

This meeting is over. You’re leaving now. Or Patricia Wells pulled out her phone. Or what? You’ll call the police? Please do. I’d love to explain to them why you’re preventing a concerned citizen from investigating potential child endangerment. Fletcher’s jaw worked, but he stepped aside. Sarah led them down the hallway to a communal bathroom.

She pointed to a sink. Ali got down on the floor, Muhammad Ali, heavyweight champion, lying on the floor of an orphanage bathroom, and reached behind the pipe. His fingers found paper folded, taped to the pipe to keep it hidden. He pulled out carefully. It was notebook paper covered in neat handwriting.

At the top it said kids who disappeared by Jenny Martinez. Below that was a list of names, 32 names. Next to each name was a date. The dates range from 1968 to 2 months ago. At the bottom of the list, Jenny had written, “They say these kids got adopted, but something is wrong. It happens too fast. And the people who take them are weird.

They smile, but their eyes are wrong. I think something bad is happening. If I disappear too, someone needs to know. Please find us. Ali stood up holding the paper. He looked at Fletcher. 32 children. Where are they? Those children were placed in loving homes through our adoption program. Show me the records.

That’s confidential. Show me the records. Fletcher’s face was a mask of barely controlled panic. I’m calling the police. You’re trespassing. Good. Ollie said, “Call them because I’m not leaving until someone with a badge sees this list.” The police arrived 15 minutes later. Two officers responding to a disturbance call.

They walked in expecting to remove a troublemaker. They found Muhammad Ali holding a piece of paper and refusing to leave. The senior officer, Sergeant William Torres, was a boxing fan. He recognized Ali immediately. “Mr. Ali, what’s going on here?” Ali handed him the paper. Read this. Then asked this man where these 32 children are. Torres read the list.

His expression changed. He looked at Fletcher. Sir, I’m going to need to see your adoption records. You have no authority. Actually, I do. This is a potential child welfare issue. I can request an immediate inspection. You can comply or I can get a warrant and come back with more officers. Your choice. Fletcher’s hands were shaking now.

I need to call my lawyer. You do that, Torres said. Meanwhile, I’m going to make sure every child in this building is accounted for and safe. What happened over the next 6 hours would later be described by investigators as one of the most disturbing child welfare cases in Illinois history. Police found 41 children in various states of neglect.

They found files in Fletcher’s office. Files never submitted to the state. Files documenting cash payments from couples who wanted children but didn’t qualify through legal channels. They found a ledger, an actual ledger, like something from a business. Names, ages, physical descriptions, and prices. Blonde children commanded higher prices.

Younger children commanded higher prices. The amounts range from $5,000 to $25,000 per child. St. Joseph’s Home for Children wasn’t an orphanage. It was a storefront for child trafficking. The scheme was horrifyingly simple. Fletcher identified children in the state system who had no living relatives, no one looking for them. He brought them to St.

Joseph’s through legitimate channels. Then he falsified records to make it appear they’d been legally adopted. In reality, they were being sold to couples who either couldn’t qualify for adoption or didn’t want to go through the legal process. 32 children over 5 years. Sold. And nobody had noticed until a 7-year-old girl wrote a letter in pink crayon to Muhammad Ali.

The arrest started that night. Douglas Fletcher was taken into custody along with three staff members who’ participated. Over the next week, investigators tracked down couples who’d purchased children. Seven were arrested. The children, now aged 8 to 17, were removed from those homes. But many of the 32 were never found.

They’ve been taken by people using false names and addresses. The money trails went cold. Those children vanished into a system that didn’t even know they existed. Muhammad Ali refused to leave Rockford until every child at St. Joseph’s had been placed somewhere safe. He rented out an entire floor of a local hotel and hired Patricia Wells to coordinate emergency foster placements.

He called in favors from everyone he knew, finding temporary homes for 41 traumatized children. And Sarah Miller Ali personally fostered her while the legal process played out. She lived with Olly and his wife for three months. While the state figured out what to do with a girl who’d exposed a trafficking ring, but had nowhere to go. During those three months, Sarah began to heal.

The scared, quiet girl who’d written that letter started to laugh. To play, to act like a child instead of a survivor. Olly enrolled her in school, took her to his training sessions. Let her eat ice cream for breakfast once because rules are meant to be broken sometimes. And every night before bed, Olly would ask, “What did you learn today?” Sarah would tell him about math, about reading, about her new friend, about how she wasn’t scared anymore.

And Olly would say, “Good. Don’t ever be scared of speaking up. You saved 32 kids by writing that letter. You’re braver than any fighter I ever met.” But the legal system didn’t know what to do with Sarah. She was in legal limbo. St. Joseph’s was shut down. Her biological parents were deceased. She had no relatives. She needed a permanent home.

Ollie wanted to adopt her, but his lawyer explained the problem. Illinois law in 1973 made transracial adoption extremely difficult. The state’s preference was to place children with families of the same race. Sarah was white. Olly was black. The courts would likely reject the adoption. That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard.

Ali said. She asked me to be your dad. I want to be your dad. What does race have to do with it? I agree it’s stupid. Patricia Wells said, “But it’s the law. Then we change the law.” And Muhammad Ali did exactly that. Over the next 6 months, while Sarah remained in his care under temporary custody orders, Ali launched what he later called the hardest fight of my life.

Not in the ring, in courtrooms, in state legislatures, in the press. He held press conferences highlighting the absurdity of a system that would rather keep a child in institutional care than let her be adopted by someone of a different race. He testified before the Illinois State Senate. He told Sarah’s story with her permission over and over again. He called in every favor he had.

He got celebrities to speak out. He got civil rights leaders involved. He made transracial adoption a national conversation. And slowly, impossibly, the system began to change. In March 1974, Illinois passed emergency legislation allowing transracial adoption in cases where no same race placement could be found within 6 months. Sarah had been waiting 8 months.

The law passed on a Tuesday. By Friday, Ali’s adoption petition was approved. On March 23rd, 1974, Sarah Miller legally became Sarah Miller Ali. She was 8 years old. But Ali wasn’t done fighting. The trafficking scheme had exposed massive holes in state oversight. Ali used his platform to push for systematic reform.

In 1974 to 1975, three states, Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin passed comprehensive child welfare reform bills known as Sarah’s laws. The legislation required mandatory reporting of all children entering state care, regular inspections of private facilities, tracking systems for adoptions, background check for facility staff, children’s right to confidential reporting of abuse, and state oversight of all private adoption agencies.

Douglas Fletcher was convicted in 1975 of child trafficking, fraud, and racketeering. He was sentenced to 25 years in federal prison. He served 17 before dying of a heart attack in 1992. Sarah Miller Ali grew up as Muhammad Ali’s daughter. She went to college. She became a lawyer specializing in family law and child advocacy.

She dedicated her career to fixing the system that had failed her. And for 45 years, she kept a relatively low profile. She did her work quietly. She helped kids. She reformed systems. But she didn’t tell her full story publicly until 2018. On September 14th, 2018, exactly 45 years after she’d written that pink crayon letter, Sarah Miller Ali published a memoir called The Girl Who Wrote to Ali.

In it, she told the complete story and revealed she’d spent 45 years tracking down 18 of the other 32 children. Some had survived and thrived, others hadn’t. She told all their stories with permission. The book became a bestseller and sparked renewed conversation about child welfare reform. In an interview, Sarah was asked why she’d waited 45 years to tell her story.

“Because my dad taught me that you don’t do good things for attention.” She said, “You do them because they’re right. He saved my life without asking for credit. He changed laws without asking for recognition. He taught me that real change happens quietly, one case at a time, one child at a time.” The interviewer asked what she remembered most about Muhammad Ali. Sarah smiled.

The pink crayon letter. He kept it in his office his whole life framed on the wall. And whenever someone asked aboutit, he’d say, “That’s the letter that taught me what courage really looks like.” A 7-year-old girl asking for help from a stranger because she trusted that someone would care.

He always said, “I was brave for writing it, but he was brave for reading it, for caring, for showing up.” Muhammad Ali died in 2016, two years before Sarah’s book was published. At his funeral, Sarah, now 50 years old, a successful attorney, mother of three, delivered a eulogy. My dad taught me three things. First, speak up even when your voice shakes.

Second, stand up for people who can’t stand up for themselves. Third, never let anyone tell you that love has a color, that family has a race, that courage has a size. A seven-year-old girl in pink crayon taught him that, and he taught the world. In 2019, the Illinois state legislature designated September 14th as Sarah’s day in honor of the letter that changed child welfare in America.

The resolution noted that reforms sparked by her case had resulted in over 2,000 children being removed from dangerous facilities, 47 child trafficking operations being shut down, and comprehensive oversight in 47 states. All because a 7-year-old girl wrote five sentences in pink crayon. And Muhammad Ali decided that a child asking for help was more important than anything else.

Today, Sarah runs the Pink Letter Foundation, working with children in foster care and adoption systems, providing legal advocacy for kids who feel voiceless. On the wall of her office is that pink crayon letter, now 51 years old, faded but preserved. Below it is a quote from Muhammad Ali. Service to others is the rent you pay for your room here on Earth.

If this story moves you, remember sometimes the most important letters aren’t eloquent or sophisticated. Sometimes their five sentences in pink crayon from a scared child. And sometimes the most important thing a powerful person can do is read that letter, believe it, and show up. Muhammad Ali could have thrown Sarah’s letter away.

Could have sent an autograph photo and moved on. Could have decided that one child in one orphanage wasn’t his problem. Instead, he drove 90 miles to meet her. He fought the system for 6 months to adopt her. He spent three years pushing for legislative reform. And he changed the trajectory of child welfare in America.

Because he believed that if a child asks for help, you help. No matter who you are, no matter who they are, no matter what the system says. Sarah Miller wrote, “I wish you were my dad.” To a stranger because she had nowhere else to turn. And Muhammad Ali made that wish come true, not just for her, but for thousands of children who came after her, who benefited from the laws that never would have existed without that pink crayon letter. That’s not just a boxing legacy.

That’s a human legacy. The kind that matters long after the championships are forgotten.

News

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word Dean Martin had…

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later Hong Kong,…

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory In 1943, the Chinese economy…

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office July 5th, 1945. Harry…

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene The coffee cup was…

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING June 18th, 1957,…

End of content

No more pages to load