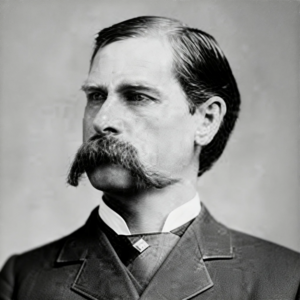

Are These Wyatt Earp Photos Even Real?

That famous photograph everyone thinks is Wyatt Herp, the one hanging in restaurants across Tombstone, the image Hollywood used for decades. Here’s the problem. Many of the photographs people believe show Wyatt Herp are misidentifications, and some are complete fakes. Despite living until 1929, well into the photographic age, historians can verify fewer than 10 photographs that definitely show the legendary law man.

How did this happen? The answer involves deliberate fraud, honest mistakes, Hollywood mythology, and the fact that nobody kept careful records. The Dodge City Peace Commission photograph from June 1883 gives us one of the few images historians accept. Wyatt sits in the front row, second from left, alongside Bat Masterson, Luke Short, and other lawmen.

The photo was taken in Dodge City during a tense standoff known as the Dodge City War. Multiple contemporary sources document who appears in this picture, making it one of the most reliable Wyatt Herp images we have. A photograph allegedly showing young Wyatt with his mother comes from collector John Gilker’s estate.

Gileries obtained materials from John Flood, who served as Wyatt’s personal secretary and inherited items directly from her before his death in 1929. When auctioneer Doug J’s inventoried Gilcree’s collection in 2003, Gil showed him this photo but refused to sell it, saying he wasn’t ready to let it go. After Gilcree’s death in 2004, his family released the photo for auction.

Historian Jeff my examined it and considered it legitimate, and PBS used it in their 2010 American Experience documentary about Wyatt Herp. Around the middle of the last century, Americans became increasingly fascinated with the Old West. Collectors and dealers hunted for photographs of famous figures. But authentic images were scarce.

Some dealers through honest error or deliberate deception started labeling unidentified photographs with famous names. Once a photograph got labeled as Wyatt Herp in a prominent collection or publication, that identification stuck even without real evidence. Photography studios in frontier towns took thousands of portraits, but rarely wrote down subjects names unless they were already famous.

Wyatt wasn’t particularly famous during his Dodge City days. He was just another law man in a rough cattle town. Years later, after the October 1881 gunfight near the Okay Corral made him notorious, people started hunting for earlier pictures. But by then, the photographers who might have remembered him were often dead or gone.

When movies and television shows about Wyatt Herp became popular in the 1950s and 1960s, actors like Hugh O’Brien and Bert Lancaster created iconic visual portrayals. Their faces became synonymous with Wyatt Herp in the public imagination. This created a feedback loop where people assumed real photographs of Wyatt should look like these actors.

If a vintage photograph showed a man with the right mustache and stern expression, it became easier to believe it showed Wyatt Herp, even without evidence. The 1994 film starring Kevin Cosner brought another layer of complexity. Filmmakers wanted authenticity, so they consulted historians and examined photographs. But if they used misidentified images as reference material, they created a portrayal partly based on the wrong face.

This is how myths perpetuate themselves. Some people use facial recognition analysis to authenticate old photographs. But this technique has serious problems when applied to 19th century images. In 2015, when a collector claimed to have found a new photograph of Billy the Kid playing croquet, one key piece of evidence was analysis by forensic expert Kent Gibson.

Gibson used computer software to overlay facial features, looking for matches. The problem? Photographic technology in the 1870s and 1880s was primitive. Long exposure times could distort facial features if subjects moved slightly. Different photographers use different techniques and equipment, affecting how faces appeared.

People also change as they age, gain, or lose weight, and alter their appearance in ways that make feature matching unreliable. When Gibson authenticated another disputed photograph in 2017, allegedly showing Billy the Kid with Pat Garrett, historians raised serious questions. The photograph had no provenence, no documented history explaining where it came from.

The authentication relied almost entirely on Gibson’s facial analysis. During the National Geographic documentary about the croquet photo, Gibson even admitted that if asked to testify in court about the match, he would deny there was one. Historians including John Bosenecker and Bob McCubbin rejected the croquet photo authentication, noting that facial recognition software simply doesn’t work reliably on two-dimensional historic images.

People who have the most to gain from authenticating disputed photographs often have financial interests. If a collector discovers that a $2 photographfrom a junk shop is actually Billy the Kid, that photograph suddenly becomes worth millions. Auction houses earn commissions based on final prices. Documentary producers need dramatic stories to attract viewers.

This doesn’t mean everyone involved is dishonest, but it means we should approach extraordinary claims with skepticism. The case of Catherine McCarti, allegedly Billy, the kid’s mother, illustrates how easily misidentifications persist. For years, a particular photograph was labeled as showing McCarti. Author Eugene Cunningham made the identification in the late 1930s, telling collector Noah Rose the photograph showed McCarti to obtain another photo he wanted.

Later, Cunningham admitted he lied and had no idea who was in the photograph. But by then, the false identification had been published and repeated. It continues to circulate today, decades after being debunked. Contemporary written descriptions say Wyatt was tall, around 6 feet, with blue eyes and light colored hair.

He wore a mustache for much of his adult life. Various people mentioned his calm demeanor and penetrating gaze. These descriptions are consistent across sources, giving us confidence they’re accurate, but they’re also fairly generic. Plenty of men in the Old West fit that description, which means photographs matching these characteristics don’t necessarily show Wyatt.

Photographs historians accept as authentic show Wyatt in his later years, probably taken in the early 1920s when he was living in Los Angeles. By this time he was a celebrity consulting on early western films. The photographs have solid provenence because they were taken when Wyatt was wellknown and photographers documented their work.

But these images don’t help much with identifying earlier photographs because Wyatt’s appearance had changed dramatically over 40 or 50 years. The question of authenticity matters for more than just historical accuracy. If the photographs we think show Wyatt Herp actually show different people, we might be drawing wrong conclusions about everything from clothing styles to social customs to the physical reality of frontier life.

Museums display these photographs as educational tools. Filmmakers use them as references. Authors reproduce them in history books. If the identifications are wrong, all that subsequent work becomes suspect. Similar problems affect photographs of other frontier figures. Doc Holiday, Johnny Ringo, the Clanton brothers, and many other Tombstone characters have disputed photographs.

The entire photographic record of the Old West needs examination with appropriate skepticism, understanding that identifications made decades later without contemporary documentation are unreliable. For historians and serious collectors, the solution involves demanding rigorous provenence before accepting any photographs identification.

Where did the photograph come from? who owned it previously? What documentation exists showing how it was identified? Are there contemporary sources confirming the identification? Without satisfactory answers, the photograph should be treated as unverified, regardless of how much it looks like what we think Wyatt Herp should look like.

For everyone else, the lesson is simpler but equally important. Approach historical photographs with critical thinking. Just because a photograph appears in a book or museum doesn’t mean it’s properly authenticated. Just because an expert verified an image doesn’t mean their methodology was sound. Just because a photograph looks right doesn’t mean it shows who we want it to show.

How many photographs of Wyatt Herp can we actually verify? Probably fewer than 10. The Dodge City Peace Commission photograph is solid. A photograph with his brothers in Tombstone around 1881 appears authentic based on contemporary documentation. A few images from his later years in Los Angeles have good provenence.

Beyond that, most photographs claim to show Wyatt Herp rely on weak evidence, questionable facial comparisons, or no documentation at all. This creates a paradox. Wyatt Herp is one of the most famous figures from the American frontier. Yet, we can verify fewer photographs of him than of many lesserknown individuals.

The reason is straightforward. During the time when Wyatt could have sat for many photographs, he wasn’t particularly famous. By the time he became famous, he was an old man and his frontier days were long behind him. The photographs people most want. Images of Wyatt in his prime as a law man in Dodge City and tombstones simply may not exist in any quantity.

The story of Wyatt Herp’s photographs is really about how we create and maintain historical myths. We want to connect with the past to see the faces of legendary figures to make history feel real and tangible. But we need to balance that desire with intellectual honesty. Acknowledging when evidence is weak or absent, even if that means accepting, we’ll never know exactly what Wyatt Herp looked likeduring his most famous years.

The next time you see a photograph labeled as Wyatt Herp, ask yourself a few questions. Where did this come from? What evidence supports this identification? Who verified it? And what were their qualifications? You don’t need to be a professional historian to ask these basic questions. Asking them doesn’t make you cynical.

It just means you’re thinking critically about evidence. If this investigation into Old West photo authentication got you thinking, drop a comment below. Which photograph surprised you most? Do you think we’ll ever definitively solve these photo mysteries? And if you want more investigations into Old West history and legend, hit that subscribe button.

There are plenty more mysteries waiting to be examined.

News

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word Dean Martin had…

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later Hong Kong,…

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory In 1943, the Chinese economy…

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office July 5th, 1945. Harry…

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene The coffee cup was…

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING June 18th, 1957,…

End of content

No more pages to load