Brad Stevens Insulted John Wayne’s Acting—What Happened Next Changed His Life Forever

Universal Studios Hollywood, August 15th, 1964. A tense western is filming. A young hotshot actor is causing problems. Brad Stevens, 24 years old, fresh from New York theater. Method actor, big ego. He’s been questioning every direction, challenging every decision. The crew is exhausted. The director is losing control.

Then Stevens makes his biggest mistake. He challenges John Wayne to a fist fight in front of 60 cast and crew members. One moment of arrogance that should end his career forever. But Wayne’s response won’t just surprise everyone on set. It will turn a cocky punk into a professional actor and create a friendship that lasts 15 years.

Here is the story. The film is The Sons of Katie Elder, Wayne’s first picture back after cancer surgery. He’s 57 years old, one lung removed, still recovering, but determined to work. The production has been smooth until Stevens arrived for his supporting role as the youngest elder brother.

Stevens studied at the actor’s studio in New York. Brando’s method. Dean’s intensity. He believes Hollywood westerns are beneath his talent. That John Wayne represents everything wrong with American cinema. Simple characters, patriotic messages, uncomplicated heroism. From day one, Stevens makes his contempt obvious. He questions Wayne’s line readings, suggests more realistic character motivations, proposes script changes to add psychological depth.

The crew watches in horrified fascination as this kid lectures the biggest star in Hollywood about acting. Wayne tolerates it for two weeks. Professional courtesy. The boy has talent, even if he lacks wisdom, but tolerance has limits. and Brad Stevens is about to find them. Stevens arrived two hours late on his first day, claiming he’d been preparing by visiting a real ranch.

“I needed to understand authentic frontier life,” he explained to director Henry Hathaway. The crew had been waiting in desert heat while Stevens communed with cattle. Wayne said nothing, just watched, but his jaw muscle was twitching. Never a good sign. By day five, Stevens was openly criticizing Wayne’s performances. Duke, don’t you think Matt should show more vulnerability here? More inner conflict? He’d call out between takes.

Wayne would stare at Stevens, then turn back to Hathaway without responding. The crew could feel the temperature dropping with each unsolicited suggestion. Day eight brought Stevens’s first direct attack on Wayne’s philosophy. During lunch, with half the crew listening, Stevens held court. The problem with traditional Hollywood acting is it’s too superficial.

These cowboys never doubt themselves, never show weakness, never explore psychological ramifications of violence. It’s emotionally dishonest. He looked directly at Wayne’s table. Audiences are too sophisticated for simple storytelling. Wayne continued eating, but crew members saw his knuckles whiten around his coffee cup.

Day 12 was when Wayne’s patients first cracked. Stevens was lecturing makeup artist Webb Overlander about authentic frontier grooming when Wayne walked by. These movie cowboys are too clean. Stevens said, “Real frontier men would have been grimy, psychologically damaged.” Wayne stopped. “Brad, you ever worked on a real ranch? Lived on one, depended on one for your living?” Steven<unk>’s confidence wavered. “Well, no, but research.

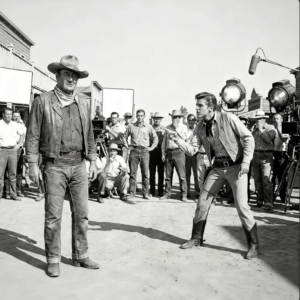

Then maybe listen to people who have instead of lecturing them about authenticity. August 15th afternoon heat baking the outdoor set. They’re filming a confrontation scene between the elder brothers. Wayne delivers his lines with trademark authority. Stevens follows with overro emotion, sighing dramatically, adding pauses and gestures not in the script.

He’s trying to show psychological complexity, but it comes across as self-indulgent performance art. Cut. Haway calls out, frustration obvious. Brad, that’s not the character. Tom Elder is direct, not tortured. Keep it simple. Stevens throws his hat down. Simple. Everything here is simple. Simple dialogue, simple emotions, simple characters. This isn’t acting.

It’s sleepwalking. He gestures toward Wayne. How can anyone grow as an artist surrounded by this museum piece approach to filmm? The set falls silent. 60 people stop what they’re doing. Stevens has just insulted Wayne. The western genre, the studio, and everyone who works in it. Wayne stands slowly, all 6’4, unfolding like a mountain coming to life.

When he speaks, his voice is quiet, but carries across the desert. Son, you got something specific you want to say to me? Stevens’s theater training kicks in. He’s performed Shakespeare in Central Park, Tennessee Williams off Broadway. serious drama at prestigious venues. He’s not intimidated by a movie cowboy, even John Wayne. Yeah, I do.

I think your whole approach to acting is outdated. I think you’re holding back everyone on this set with your one-dimensional performance. I think it’s time someone told you the truth about how limited your range really is. The words hang like gunshot smoke. Crew members exchange glances, waiting for the explosion.

Wayne’s legendary temper is about to destroy this young actor’s career before it begins. But Wayne surprises everyone. Instead of anger, he smiles, not friendly, but calculating like a chess master seeing his opponent’s fatal mistake. Brad, you think I’m not a real actor? Stevens’s chin juts forward. I think you’re a movie star. There’s a difference.

Movie stars play themselves. Actors disappear into characters. Wayne nods thoughtfully. You think what I do is easy? Stevens shrugs. I think what you do is limited, safe, unchallenging. You play the same character every movie. Strong, silent, morally certain. [clears throat] Where’s the growth? The artistic risk limited. Wayne tastes the word.

Tell you what, son. You seem confident about your abilities. How about we settle this like men? Stevens’s chest puffs out. Here it comes. The old cowboy wants to fight. Stevens was a boxer at NYU. Stays in shape. Trained in stage combat. He’s 24 and at his physical peak. Wayne is 57, recovering from surgery, missing a lung.

Stevens can take him easily. You want to fight me? Stevens asks, already imagining the story he’ll tell about knocking out John Wayne. Wayne’s smile widens. Almost predatory. Something like that. But not with fists, Brad. With acting. Stevens blinks. This isn’t what he expected. Wayne continues, voice gaining authority.

You think I’m limited? You think what I do is easy? Prove it right here, right now. Show everyone how much better your method is than my limitations. Wayne gestures to Hatheraway. Henry, give us that scene from yesterday where Tom tells his brothers about their father’s death. Brad’s going to show us how it should really be done.

Haway’s eyes light up. He’s seen Wayne turn attacks into teaching moments before. You want the whole speech, Duke? The whole thing? But Brad’s doing it my way first. Simple, direct. No psychology, no method, no New York tricks, just honest emotion. If it’s so easy and limited, this should be cake for a trained actor.

Stevens realizes he’s trapped, refuse, and look weak. Accept and risk humiliation. But his ego won’t let him back down. Fine, I’ll show everyone how it should be done. My way first, then yours, so we can compare approaches. Wayne steps back, gives Stevens the stage. The crew gathers, sensing something special.

Stevens takes position, prepares mentally like he’s trained. He thinks about his father, about loss, grief, psychological impact of sudden violence. He builds emotion from inside, layers it with complexity, draws on Stannislovski’s method, Strawber’s emotional memory techniques, everything the actor studio taught him. He begins the scene.

Voice waivers with constructed pain. face shows internal conflict, psychological trauma. Body language suggests a man barely holding together, fighting demons threatening his sanity. He pauses for psychological beats, uses silence to convey turmoil. Every technique about showing rather than telling. It’s technically proficient, emotionally rich, dramatically compelling, and completely wrong for the character.

When Stevens finishes, there’s polite applause. Good acting, they think, but it doesn’t feel like Tom Elder. It feels like Brad Stevens performing grief, showing off training, demonstrating technique. Impressive, but not believable. Wayne steps forward. Nice work, Brad. Very complex, very psychological, very New York. Now watch.

Wayne takes the same position. He doesn’t prepare mentally, doesn’t build emotion, doesn’t think about method or technique. He just becomes Tom Elder, a man who’s lost his father to murder and needs his brothers to understand why justice matters more than safety. When Wayne speaks the same lines, something magical happens. The words carry weight of a man who’s lost everything but won’t break.

The emotion is simple but devastating. Real but not showy. Strong but not invulnerable. There’s grief in his voice but controlled grief. Purposeful grief. Grief transformed into determination. The crew is transfixed. This is why John Wayne is John Wayne. Not because he’s limited, but because he makes complex looks simple, finds universal truth inside specific circumstances.

Serves the story instead of his ego. Wayne finishes. The silence that follows is different. Not awkward waiting, but recognition. Everyone just witnessed the difference between acting and being, between technique and truth, between showing off and showing up. Finally, Grip supervisor Mickey Moore starts clapping slowly, then with growing enthusiasm.

The crew joins in, applauding with genuine appreciation for what they’ve seen. Wayne turns to Stevens, voice gentle now, but carrying absolute authority. Brad, let me explain something. What you did was very good acting. technically excellent, emotionally complex, but it was Brad Stevens showing us how Tom Elder might feel.

What I did was Tom Elder actually feeling it. Stevens stares, arrogance deflating like a punctured balloon, certainties crumbling like cards in wind. Wayne continues, “You think what I do is simple because you see the result, not the process. You think it’s easy because I make it look effortless. But son, making something look effortless when it’s actually difficult, that’s not limitation. That’s mastery.

The lesson isn’t over. Wayne has more to teach. And now he has Stevens’s complete attention. You want to know the hardest thing about acting, Brad? It’s not showing the audience how much you can do. It’s only doing exactly what the character needs. Nothing more, nothing less. Your performance was about showing us your skills.

Mine was about Tom Elder living his truth. Wayne steps closer. You showed us technique, training ability. Very impressive. But you forgot to show us Tom Elder. The audience doesn’t care how well you can act. They care if they believe you are the character. Stevens looks around at the crew, seeing respect in their eyes for Wayne.

Disappointment for him. He’s been schooled publicly, but not with cruelty. With wisdom, with patience, with teaching that builds up instead of tears down. Mr. Wayne, I think I understand, do you? Then let’s try again. But this time, don’t show me Brad Stevens acting. Show me Tom Elder living. Stevens takes position again.

Confidence shaken, but willingness to learn growing. This time, he doesn’t prepare, doesn’t build, doesn’t think about technique or method. He just tries to be Tom Elder. Simple and honest and direct. It’s not perfect, but better. Much better. The psychological showboating is gone, replaced by something honest, direct, real.

The crew murmurs approval. Wayne nods with satisfaction. That’s it, son. That’s the difference between acting and pretending, between showing off and showing truth. You just learned more about acting in 5 minutes than most people learn in 5 years. Haway calls a break, but Stevens approaches Wayne privately. Mr.

Wayne, I owe you an apology and an explanation. Wayne sits on a nearby rock, gestures for Stevens to join him. I’m listening, son. Stevens takes a deep breath. I came here thinking I was better than this. Better than westerns, better than Hollywood, better than you. I was wrong about everything. Wayne’s expression softens.

Stern teacher becoming patient mentor. Brad, let me tell you something. I’ve been doing this for 35 years. I’ve worked with some of the greatest actors who ever lived. Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, Morino O’Hara, Montgomery Clif. Everyone brought something different to their work. He pauses, choosing words carefully.

But the best ones, the ones who lasted, they all understood one thing. The camera sees everything. It sees through tricks, through technique, through pretense. It only respects truth. Stevens nods, beginning to understand. Your training is valuable, son. Don’t throw it away. But use it to find truth, not to show off. Use it to serve the character, not to serve your ego.

Wayne stands, brushing dust off his chaps. And Brad, there’s nothing wrong with being proud of your craft. But there’s a difference between confidence and arrogance. Confidence serves the work. Arrogance serves itself. From that day forward, Stevens becomes Wayne’s unofficial apprentice. He watches how Wayne works with other actors, approaches each scene, finds emotional core without drowning in psychology.

He sees Wayne help struggling performers, guide new actors, share knowledge freely with anyone willing to learn. Stevens realizes Wayne’s strength isn’t just screen presence. Its generosity as a craftsman and understanding that great acting lifts everyone around it. Stevens’s performance in The Sons of Katie Elder becomes his breakthrough role.

Critics praise his surprisingly grounded work, his natural charisma, his authentic presence. None know about the masterclass Wayne gave him in front of 60 Witnesses, or the weeks of quiet mentoring that followed. The film wrapped successfully in October 1964. Stevens, humbled and educated, thanks Wayne personally.

Duke, I learned more from you in 3 months than 3 years at the actor’s studio. Wayne smiles. Warmer now, more fatherly. Brad, the actor studio taught you how to act. I just reminded you how to be. Stevens goes on to have a solid career in westerns and action films, appearing in over 40 movies over 25 years. Never a superstar, but a respected character actor who works steadily and earns respect of peers.

He credits Wayne in every interview, though rarely tells the full story. Too personal. too revealing of his former arrogance. But when young actors ask about stage versus screen acting, he tells them about the day John Wayne taught him that the camera sees everything, especially the truth. In 1979, when Wayne dies of cancer, Stevens is one of the mourers.

He tells Wayne’s son Patrick about that day on set, about the challenge that became a lesson, the fight that became friendship. Your father could have destroyed me with one word to any studio head in town, Steven says. Instead, he made me better. He turned my biggest mistake into my greatest lesson. Patrick asks what his father said that made the difference.

Stevens thinks carefully. He showed me that true strength doesn’t prove itself by crushing opposition. It proves itself by lifting others up. I challenged him to a fight and he gave me an education instead. Today, when film students study Hollywood’s golden age, they sometimes hear about the confrontation between John Wayne and Brad Stevens.

It’s told as an example of how real professionals handle disrespect, how true masters create other masters instead of just defending territory. Stevens, now in his 70s, teaching acting at a small Oregon college, still tells the story to students. Duke Wayne wasn’t just a great actor. He always concludes he was a great teacher and the best teachers are the ones who turn your arrogance into wisdom without destroying your spirit in the process.

Meanwhile, recently you were liking my videos and subscribing. It helped me to grow the channel. I want to thank you for your support. It motivates me to make more incredible stories about Hollywood’s greatest legends. And before we finish the video, what do we say again? They don’t make men like John Wayne anymore.

News

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word Dean Martin had…

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later Hong Kong,…

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory In 1943, the Chinese economy…

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office July 5th, 1945. Harry…

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene The coffee cup was…

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING June 18th, 1957,…

End of content

No more pages to load