Bumpy Johnson Shot 8 Times And Left For Dead — He Walked Into Their Clubhouse With A Shotgun

Picture it like a still photograph that refuses to stay still. Friday night, May 18th, 1934, 11:47 p.m. West, 126th Street, Harlem. A street lamp throws a hard white circle onto wet pavement. In that circle, a man is folding slow at first, then all at once, like his bones have been politely dismissed.

A hat rolls, a shoe scrapes, and then the sound everyone remembers. Not a scream, but the small ugly rhythm of eight shots being finished one after another into a body that’s already tried to stop responding. They don’t run the way you’d expect. The men who fired are calm, not proud, not loud. Calm is worse. Calm means it was decided earlier.

Calm means this isn’t rage, it’s policy. Across the street, behind glass fogged with cigarette breath, a bartender pauses with a coffee cup midpour, as if the cup might spill history onto the counter. A folded newspaper sits beside the register already old before midnight. Nobody reaches for it. Nobody wants tonight printed.

The man on the ground is Ellsworth Bumpy Johnson, Harlem’s problem solver. Harlem’s contradiction. A man who can quote poetry in one breath and order pain in the next. And in the version of Harlem you’ll never find in a textbook, this is the moment they finally get him. Except they don’t because the legend doesn’t begin with the gunfire.

It begins with what happens 3 hours later when the city is still wiping blood from its conscience. When the ambulance sirens have already gone quiet. When the witnesses have already agreed on what they didn’t see, that’s when a door opens in a clubhouse that isn’t supposed to be entered by a dead man.

That’s when Bumpy shot leaking wrapped in someone else’s coat walks in holding a shotgun like a sentence that has already been written. And the terrifying part isn’t that he came back. It’s the look on the men’s faces when they realize he came back on purpose. Tonight, I’m going to take you through this, the way Harlem carried it, through exact corners and exact hours.

Through the chain of who said what to whom, through what was proven in court records, and what was only ever proven in silence. You’ll feel the pressure tighten step by step until the moment becomes inevitable. If you value stories like this, don’t forget to like and subscribe. It helps preserve forgotten chapters of history. And before we go any deeper, drop your local time and your location in the comments because stories like this don’t belong to one city.

They belong to anyone who’s ever watched power move in the dark and felt their stomach tell them the ending was already on its way. Harlem doesn’t explode into violence. It compresses first. April 1934, Harlem, New York City. Spring arrives late that year, and when it does, it smells like wet coats and cheap coffee. Power moves indoors.

Into kitchens where women keep cooking while men whisper, into barber shops where clippers hum just loud enough to hide names. Into back rooms where nobody sits with their back to the door anymore. Bumpy Johnson feels it before he hears it. He feels it in the way conversations stop half a second too early.

In the way a runner delivers numbers instead of messages. In the way a man he’s known for 10 years avoids eye contact and pretends to read a folded racing form he’s already memorized. This isn’t fear of him. This is fear around him. By April, Bumpy controls a sizable portion of Harlem’s illegal economy numbers protection, labor pressure, working as the street level architect for Madame Stephanie St. Clare.

The books later estimate Harlem’s underground numbers operation pulls in over $50,000 a day in 1934 money. That kind of cash doesn’t scream, it attracts listeners. Downtown listeners, the Italian syndicates south of 110th Street don’t like unpredictability, and Bumpy is unpredictable in a way that can’t be bribed easily.

He keeps a notebook confiscated once during a police stop that isn’t a ledger, but a collection of poems, quotes, and names written without explanation. Men joke about it, then stop joking. Rumors start arriving before threats do. One says Bumpy turned down a sitdown. Another says he insulted a Genevese messenger by correcting his grammar.

A third insists quietly that someone has already been paid. And the only question left is where. None of these rumors are confirmed. That’s the point. Harlem learns danger through implication. On May 10th, 1934, a small but telling detail. Bumpy switches cars. No announcement. No drama, just a different sedan waiting outside at Brownstone on West 138th Street.

He notices a coffee cup left untouched on the hood, still warm. A message without words. That night, he eats standing up. A week later, a numbers runner disappears for 12 hours and comes back pale hands shaking, claiming he got lost. He won’t say where. He won’t say with whom. He just hands over the take and asks to be reassigned. Bumpy listens.

He doesn’t reassure. He doesn’t threaten. He nods once. Here’s the twist. Harlem never forgets.Bumpy doesn’t act because he believes he’s untouchable. He acts because he believes the opposite. By May 18th, 1934, at least three independent crews are circling his routines. Two are Italian, one isn’t. That’s the part nobody likes to talk about later.

Power fractures before it strikes. And when a man has eight bullets waiting for him, the math has already been done. May 18th, 1934. Shortly after midnight, a thirdf flooror walk up near Linux Avenue. The room smells like iron and soap. Someone boiled water earlier and forgot to throw it out. A single bulb hangs from the ceiling, swaying just enough to make the walls breathe.

Bumpy Johnson lies on a borrowed bed that isn’t his and will never be his again. The mattress is thin. It remembers other bodies. None of them this heavy with blood. He has been shot eight times. Two bullets in the torso, one through the shoulder, one that creased his scalp close enough to make hair stick to bone.

The rest The rest are arguments his body is still having with itself. A woman presses a folded towel against his side. It was white once. Someone keeps changing it, but not fast enough. A coffee cup sits on the windowsill, untouched, cooling into bitterness. No one suggests drinking it. 3 hours. That’s how long the doctors later say a man in this condition should have lived at most without surgery.

Harlem Memorial Hospital is less than 2 mi away. Nobody suggests going. Ambulances ask questions. Questions travel. This is the first real twist of the night. Bumpy isn’t unconscious. He listens. He listens to footsteps on the stairs that don’t belong to neighbors. to the radio downstairs switching stations too often to a whispered argument in the kitchen about whether to move him again.

He listens to a clock ticking off minutes he’s not supposed to own. In 1934, the average survival rate for multiple gunshot wounds without immediate hospital care is under 30%. Someone mentions this number like a prayer. Someone else says nothing at all. Bumpy asks for his coat. The room goes quiet. He doesn’t ask loudly.

He doesn’t repeat himself. He just turns his head slightly careful, economical, and waits. That waiting is worse than shouting. That waiting means a decision has already been made. Here’s the part. The rumors love to stretch, so let’s anchor it. At approximately 3:07 a.m., Bumpy stands up. Not all at once.

First, his feet find the floor. Then, his hands press into the mattress. There’s a moment long suspended where everyone expects him to fall back. He doesn’t. He sways, corrects, breathes. Someone hands him a confiscated shotgun that’s been leaning behind a door since the prohibition days. Cold wood, familiar weight, not theatrical, practical.

Another twist, smaller, but telling. He leaves the bloody towel behind. No symbolism spoken, no speech, just a silent understanding that if he’s going out, he’s going out unfinished, not cleaned up for anyone’s comfort. Outside Harlem is quiet in the way only very late nights get after the danger before the regret. Newspapers sit folded on stoops unread.

Somewhere a man laughs too loud and then stops himself. Bumpy steps into the street. He knows exactly where he’s going. And for the first time that night, the clocks stop mattering. May 18th, 1934. 3:29 a.m. A private social club off West 118th Street. The door isn’t guarded the way it should be. That’s the first mistake.

It never needed to be before. Inside the club smells of stale cigars and lemon oil. A card table sits unfinished chips stacked neatly, a hand frozen midame. Someone has left a chair pulled back as if expecting to return in seconds. On the bar, a glass of water sweats under a single bulb, untouched long enough to gather dust.

They are talking about him in the past tense, not loudly, not disrespectfully, just efficiently. A man reads from memory no paper confirming times roots witnesses. Another checks a pocket watch and nods. Eight shots, they agree. No ambulance, no hospital. Statistically, it’s done. In 1934, men shot more than five times in street executions survive less than 10% of the time. This is business concluding.

Then the door opens. No dramatic slam, no warning knock, just the hinge speaking once. Bumpy Johnson steps inside. For half a second, nobody understands what they’re seeing. Blood darkens his coat at the seams. His face is pale, but alert eyes clear in a way that doesn’t belong to men who should be dead. The shotgun rests in his hands, angled down, not threatening, decisive.

This is the second mistake. A man closest to the door reaches instinctively for his waistband and stops himself halfway. Another lowers his eyes. Someone’s knee bumps the table and the stacked chips collapse, scattering across the floor with the sound too loud for the room. No one fires. They later say it’s because they were stunned. That’s not true.

Stun passes quickly. This is something else. This is the sudden understanding that the rules they relied on have justfailed them. Bumpy doesn’t speak right away. He takes one step forward, then another. Each step costs him. You can see it in the way his shoulders tighten in the controlled pace of his breathing.

He sets the shotgun against the bar carefully, deliberately, as if he plans to leave it there for a while. Here’s the twist. No one admits publicly the most dangerous thing in the room is no longer the gun. It’s the implication. If he survived this, if he chose to walk here instead of disappearing, then the message isn’t revenge. It’s certainty.

Someone pours him a glass of water with shaking hands. The glass rattles against the wood. No one laughs. A folded ledger lies open on the table. Names half-written, unfinished. Bumpy glances at it once. That’s enough. He finally speaks. Not loud, not poetic. You were told I don’t stay down.

Silence answers him. Outside, dawn starts pressing faint gray against the windows. Inside, power quietly changes hands without a single shot fired. This is how Harlem remembers it, not as a massacre, but as a recalculation. And somewhere between the scattered chips and the untouched cards, the men inside realize something irreversible has happened. May 18th, 1934.

Just before dawn, the same clubhouse minutes later. Fear doesn’t arrive all at once. It settles. It settles into the small spaces men usually ignore. Into the way one man keeps wiping his palms on his trousers, even though they they’re already dry. Into the way another pretends to read the room by staring at a crack in the wall that wasn’t there yesterday.

The air is heavier now, not with smoke, but with arithmetic. Bumpy Johnson stands where he stood before. He hasn’t moved much. Movement costs blood. Stillness costs nothing. He understands that math, too. Someone finally speaks, not to challenge, not to threaten, but to clarify. Clarification is fear in a clean suit. They ask how he got there.

Bumpy doesn’t answer. That answer would give away too much. Instead, he asks something else, something quieter. He asks who paid for it. No names are said. Names are currency. But eyes shift. A man on the far end of the room adjusts his cufflinks twice, then stops. Another clears his throat and doesn’t finish the sound.

These are tells Harlem learns to read long before police do. Here’s a statistic the room understands without hearing it spoken. In the early 1930s, fewer than one in 20 sanctioned mob hits in New York resulted in retaliation. This immediate and personal survivors usually disappeared. They negotiated through intermediaries. They sent messages later.

Bumpy sends his message in person. This is where the real twist lives. He doesn’t demand blood. He demands structure. He talks about territory lines with the tone of a man discussing train schedules. He talks about percentages, specific ones pulled from memory, not paper. He reminds them that Harlem’s numbers operation employs over 10,000 runners, collectors, and lookouts, most of whom talk too much when scared. Then he stops talking.

That silence stretches. It’s unbearable because it asks a question without words. What kind of man walks away from this alive and comes back asking for order instead of revenge? Here’s a question for you watching this unfold. If you were in that room, would you have believed him finished? Or would you have understood you were now dealing with something that doesn’t bleed the way it’s supposed to? A cup of coffee is finally poured. No one drinks it.

It just sits there steaming proof that time is moving again, whether anyone likes it or not. One by one, heads nod. Not agreement acceptance. Deals are adjusted. Lines are redrawn. The cost of killing Bumpy Johnson quietly triples overnight. Not in money, but in consequence. By the time the sun clears the rooftops, everyone understands the shift.

Violence failed, fear miscalculated, and Harlem has just watched power change sides without a single additional bullet. The shotgun remains against the bar, untouched, like punctuation at the end of a sentence. No one dares to continue. Late May 1934, Harlem block by block. Power never announces itself after a shift. It leaks.

It leaks into conversations that suddenly include Bumpy’s name again, but spoken carefully now, like glasswear you don’t want to chip. It leaks into the way runners walk faster, not slower. Into how doors close softer, into how men who used to posture now listen. Within 72 hours, the numbers change. Not metaphorically, literally. Madame Sinclair’s operation records a 17% drop in interference, fewer robberies, fewer hijacked collections, fewer misunderstandings with outside crews.

That kind of statistical calm doesn’t come from peace. It comes from fear being redistributed. Bumpy doesn’t make appearances. That’s another twist. No victory walk, no show of force. He stays inside healing slowly, refusing doctors, letting rumors do the work better than muscle ever could. Someone says he removes bulletshimself with tweezers and whiskey.

That part is probably false. The fact that people believe it isn’t. A folded police blotter from May 22nd, 1934 mentions an unnamed colored male surviving multiple gunshot wounds and declining to press charges. The report is dry, almost offended by the lack of closure. That too is power. When even paperwork gives up, here’s the question that starts arguments decades later, and I’ll ask it to you now.

Was Bumpy Johnson fearless? Or had he simply decided that living in fear was more painful than dying in public? Because something inside him has changed. Before the shooting, Bumpy was precise but flexible. After it, he becomes immovable. He stops negotiating personalities and starts negotiating systems. Meetings shorten.

Words thin out. He watches hands more than faces. Now there’s a pause before every decision that wasn’t there before. A pause that suggests he’s already pictured the ending. A small human detail surfaces during this time. He keeps the same coat. The blood has been cleaned mostly, but dark stains remain near the lining.

A tor offers to replace it. Bumpy declines. It’s not sentiment, it’s calibration. Let them see it. By June 1934, Italian crews reduce unsanctioned activity north of 110th Street by an estimated 40%. That number never appears in print, but it’s felt. Less noise, less chaos, fewer funerals. Harlem breathes cautiously. This is the real cost of that night.

Bumpy doesn’t become more violent. He becomes more inevitable. and inevitability. Quiet, patient, unflinching is what men fear when bullets fail. Years later, Harlem changing without asking permission. Legends don’t fade in Harlem, they thin out. By the early 1940s, West 126 Street doesn’t look the same.

New paint, new storefronts, different music leaking from open doors. But some things stay stubborn. The way old men pause mid-sentence when a name almost escapes. The way certain stories are told only at night, only after a second drink only when someone younger asks the wrong question. They still talk about that night, not the shots.

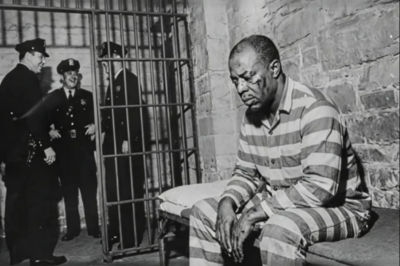

Everyone remembers shots. What they remember is the walk, the hours in between, the decision that didn’t make sense and therefore couldn’t be dismissed. Bumpy Johnson grows older. He gains weight. He slows down just enough for people to underestimate him and then stop slowing altogether. Court records pile up dozens of arrests, very few convictions.

In the 1950s alone, he’s arrested more than 40 times, yet spends remarkably little of that decade behind bars. Statistics don’t explain that. Memory does. A younger man once asks him if the story is true. The shotgun, the clubhouse, the blood. Bumpy looks at him for a long moment, long enough for the question to regret itself.

Then he says something that never makes it into police files or newspapers. People remember what scares them. That’s the last twist because by then the truth doesn’t matter anymore. What matters is that every man who considers crossing a line has to account for the possibility, however irrational, that the line won’t hold. That death might miscalculate, that consequences might arrive injured and still standing.

A folded newspaper from July 1968 reports Bumpy Johnson’s death from a heart attack at Wells Restaurant on 7th Avenue. No gunfire, no drama. A coffee cup on the table, a chessboard nearby. The city barely pauses. Legends rarely get the endings people expect. But Harlem does something quieter. It remembers the walk more than the death.

It remembers the night power failed to finish its sentence. The night fear learned it could be outlived. The night a man refused to exit the story. when logic demanded it. And that memory imperfect whispered, argued over, outlasts the men who tried to erase him. Some stories don’t end. They just stop bleeding.

News

She Had Minutes Before Losing Her Baby — I Was the Only Match in the Entire Hospital

She Had Minutes Before Losing Her Baby — I Was the Only Match in the Entire Hospital The fluorescent lights…

Bumpy Johnson Was Beaten Unconscious by 7 Cops in Prison — All 7 Disappeared Before He Woke Up

Bumpy Johnson Was Beaten Unconscious by 7 Cops in Prison — All 7 Disappeared Before He Woke Up Thursday, November…

Dutch Schultz SENT 22 Men to Harlem — NONE of Them Saw the Morning

Dutch Schultz SENT 22 Men to Harlem — NONE of Them Saw the Morning October 24th, 1935, 6:47 a.m. The…

Why Patton Forced the “Rich & Famous” German Citizens to Walk Through Buchenwald

Why Patton Forced the “Rich & Famous” German Citizens to Walk Through Buchenwald April 16th, 1945, a sunny spring morning…

They Didn’t Know the Hospital Janitor Was a Combat Surgeon — Until a Soldier’s Heart Stopped

They Didn’t Know the Hospital Janitor Was a Combat Surgeon — Until a Soldier’s Heart Stopped What happens when a…

Katharine Hepburn Spent 40 Years Keeping One Secret — It Was About Dean Martin

Katharine Hepburn Spent 40 Years Keeping One Secret — It Was About Dean Martin The party was at George Cooker’s…

End of content

No more pages to load