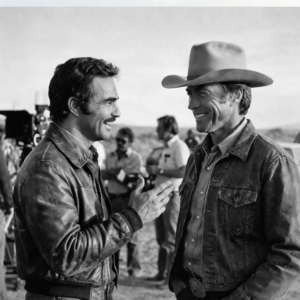

Clint Eastwood BET Burt Reynolds $10,000 He Couldn’t Do This Stunt—What Happened NEXT

Arizona, 1978. The desert heat shimmerred off the hood of a black Trans Am like liquid mercury. It was the kind of heat that made your teeth ache and your vision blur. The kind of heat that made men do stupid things. Bert Reynolds stood next to a wooden ramp that looked like it had been built by someone with a death wish.

The ramp stretched 30 ft into the air, angled toward a canyon that dropped 200 f feet straight down. On the other side, maybe maybe 50 feet away, was another ramp. Clint Eastwood stood 10 feet from Bert, arms crossed, that famous squint even more pronounced in the brutal sun. The film crew had stopped working. Cameras sat idle. Nobody moved.

Everyone knew something was about to happen, something they’d be talking about for the rest of their lives. “You’re serious,” Clint said. It wasn’t a question. Bert flashed that million-dollar grin as a heart attack. You’ll kill yourself or I’ll win 10 grand. Bert gestured toward the canyon. What’s it going to be, Clint? You backing out? The tension between them was thick enough to cut.

These weren’t just two actors on a film set. These were the two biggest action stars in Hollywood. Two men who’d built their entire careers on never showing fear, never backing down, never admitting they couldn’t do something. And now in front of 40 crew members, one of them was about to prove it. To understand what happened that day, you need to understand who these men were in 1978.

Bert Reynolds was the biggest box office star in the world. For three consecutive years, he’d been number one. Smokey and the Bandit had made him a household name. He was charming, funny, impossibly handsome, and he did his own stunts. All of them, it was his signature, his pride.

Clint Eastwood was the man Bert wanted to be. Cooler, more respected. Clint didn’t need to smile or crack jokes. He just stood there and the camera loved him. He’d gone from spaghetti westerns to American classics. Directors fought over him. Critics respected him. They’d never worked together before this film. The studio had pushed for it.

Reynolds and Eastwood, the ultimate action picture. But from day one, there was tension. Not hatred, not dislike. Something more complicated. Respect mixed with competition. They were too similar. Two alpha males. Two men who’d clawed their way to the top and refused to show weakness. On set, they were professional, polite, but everyone could feel it.

The unspoken question hanging in the air. Who’s really the toughest guy here? It started small. Bert would do a stun in one take. Clint would watch, then do his in one take. Bert would add a flourish. Clint would add something bigger. By week three, they weren’t making a movie anymore. They were in a contest. And then came the day with the canyon.

The stunt wasn’t even in the script. The scene called for Bert’s character to drive across a narrow bridge. Simple, safe. But when Bert saw the canyon location, saw that ridiculous ramp the stunt coordinator had built for a different shot, something sparked in his brain. “I could jump that,” Bert said casually during lunch.

The stunt coordinator, a weathered man named Eddie, laughed. “No, you couldn’t. Nobody could. That’s a 50ft gap over a 200 ft drop. The margin for error is zero.” Clint was sitting nearby. He heard everything. Eddie’s right, Clint said, not looking up from his sandwich. That’s a stunt driver job. Might even be too dangerous for a stunt driver. Bert’s jaw tightened.

You saying I can’t do it? I’m saying it’s stupid to try. But if someone could do it, Bert leaned forward. Hypothetically, would that someone be braver than someone who wouldn’t try? Clint finally looked up. Brave and stupid aren’t the same thing. Maybe, maybe not. Bird stood. Tell you what, Clint, I’ll bet you $10,000 I can make that jump. The film set went quiet.

$10,000 in 1978 was serious money. That was a down payment on a house. That was a new car. But more than that, this was about pride. Clint studied Bert for a long moment. Then he stood, “You’re really going to do this. If you take the bet, and if you die,” Bert’s grin widened. then you won’t have to pay me.

Clint should have walked away. Should have laughed it off. Should have been the mature one. But 40 people were watching. And Clint Eastwood had never backed down from anything in his life. He extended his hand. You’re on. They shook and Bert Reynolds sealed his fate. Clint Eastwood walked back to his trailer 30 minutes later and for the first time in years, his hands were shaking.

What the hell did I just do? He’d seen men die on film sets. He’d been there in 1973 when a stunt went wrong. He still remembered the sound, still saw it sometimes when he closed his eyes. And now he just bet $10,000 that Bert would jump a canyon professional stunt drivers called impossible. There was a knock on his trailer door.

The director poked his head in. Clint, Bert’s serious. He’s out there checking the Trans Am right now. Iknow the studio will shut us down if Tom. Clint’s voice was quiet. How do I stop him? Tom hesitated. You can’t. Not now. Not after the bet. Not with everyone watching. Bert would rather die than look weak in front of you.

Clint knew he was right. Bert Reynolds would literally rather die than back down. Then we make it as safe as possible. Clint said, “Get Eddie. Every safety measure we have.” But even as he said it, Clint knew the truth. You can’t make jumping a 50-foot canyon safe. The bet had been made. The crew was watching, and Bert Reynolds was about to risk his life because Clint Eastwood’s ego couldn’t let him walk away from a challenge.

Clint sat down heavily, put his head in his hands, and for the first time since he was a boy, Clint Eastwood prayed. Bert sat in the driver’s seat of the Trans Am, hands on the steering wheel, breathing slowly. The car smelled like oil and leather and fear, though Bert would never admit the last part. Through the windshield, he could see the ramp.

From this angle, it looked even more insane. A wooden structure that seemed too flimsy to hold a bicycle, let alone a 3,000lb car going 70 mph. Eddie was on his knees next to the driver’s window. Bert, listen to me. You hit that ramp at exactly 72 mph. Not 70, not 75, 72. You understand? I understand. And when you’re in the air, and you’re going to be in the air for about 3 seconds, don’t touch the wheel.

Don’t touch the gas. Don’t do anything. Just hold steady. Got it. Eddie’s voice dropped. Bird. I’ve been doing this for 20 years. I’ve seen stunts that looked impossible. But this, he trailed off. You don’t have to do this. Nobody will think less of you. Bert turned and looked Eddie in the eye. Yes, they will, especially me.

Eddie nodded sadly and stepped back. The crew had set up cameras at every angle. If Bert died, at least it would be well documented. Clint stood near the edge of the canyon, hat pulled low, face unreadable, but his jaw was tight. His hands were clenched. He was a man watching something he’d caused, but couldn’t stop.

Bert took one more breath, looked at the ramp, looked at the canyon, looked at Clint. Then he turned the key. The Trans Am roared to life. The engine screamed. Bert dropped it into gear. Punched the gas. The Trans Am shot forward like a bullet. Sand sprayed. The engine howled. The speedometer climbed. 40 50 60. Eddie was screaming something.

Bert couldn’t hear him over the engine. 70 71 The ramp was rushing toward him. It looked impossibly small, impossibly fragile. 72 Bert’s foot stayed flat on the gas. The tires hit the ramp. The world tilted and then silence. The Trans Am left the ground for 3 seconds. Bert Reynolds flew. The car hung suspended over a 200 ft drop.

Through the windshield, he could see the far ramp. It looked a thousand m away. Time stretched, slowed. Bert could hear his own heartbeat, could feel every molecule of air, could see the whole desert laid out below him like a painting. This is it, he thought. This is what living feels like. The car began to drop.

The far ramp was coming, but something was wrong. The angle, the trajectory. The Trans Am was coming in too low, too fast. Bert saw it a split second before impact. They weren’t going to make it cleanly. The front tires hit the edge of the ramp. The back tires hit nothing but air. The Trans Am’s front end slammed into the ramp with a sound like a bomb. Metal shrieked.

Wood exploded. The rear of the car whipped sideways. For a moment, everything was chaos. The car spun. The ramp collapsed. Bert’s head snapped forward, then back. His vision went white, then black, then white again. When his eyes focused, he was looking straight up at the sky. The car had come to rest on its side, half on the ramp, half hanging over the canyon edge. Bert couldn’t move.

His ribs screamed. His neck felt like it had been replaced with broken glass. He tried to lift his arm. It wouldn’t respond. Through the shattered window, he could see the drop. 200 ft of nothing, and the car was sliding slowly, inch by inch. The destroyed ramp was giving way beneath the weight. The Trans Am was tipping toward the canyon.

Bert tried to scream. Nothing came out. He could hear shouting, running feet. Someone was calling his name. The car slid another foot. Metal groaned. Bert’s chest wouldn’t expand. He couldn’t breathe, couldn’t move, couldn’t do anything but watch as the nose of the Trans Am tilted further and further over the edge.

This is how it ends, he thought. I bet $10,000 and lost everything. Then a hand grabbed his shoulder. Clint Eastwood didn’t remember running. One second he was standing by the canyon edge, frozen in horror. The next second he was at the car, his hands grabbing Bert’s jacket, pulling with strength he didn’t know he had. Don’t you die, Clint was saying.

He wasn’t aware he was speaking. Don’t you dare die on me. The car groaned, slipped another inch. Eddie and three crew members appeared. They grabbed the car’sframe, trying to anchor it, but it was too heavy. The ramp was too destroyed. “We need a rope,” someone screamed. “No time,” Clint yelled back. He wrapped both arms around Bert’s chest and pulled.

Every muscle in his body strained. He could feel something tearing in his shoulder. “Didn’t care. Bert’s body moved 6 in, then stopped. His leg was caught on something. The car slipped again, further. The front wheels were now completely over the edge. Clint looked into Bert’s eyes. Bert was conscious barely. His lips were moving. “I’m sorry,” Bert whispered, blood on his teeth. “Shut up,” Clint said.

“You’re not dying. You hear me? You don’t get to die. Not over a stupid bet. Not over my stupid ego.” Clint braced his feet, pulled again. Something in the car gave way. Bert’s body came free. Clint fell backward. Bert on top of him. They rolled once, twice, away from the car.

And just as they cleared the ramp, the Trans Am gave up its fight with gravity. It tipped. It fell. 200 ft down. It hit the canyon floor with a sound like the end of the world. Clint lay on his back, bird across his chest. Both men breathing in ragged gas. The film crew stood in a circle around them, silent, shocked. Clint felt wetness on his face. He thought it was blood.

It was tears. The hospital in Tucson smelled like disinfectant and bad coffee. Bert Reynolds lay in a bed wrapped in more bandages than a mummy. Three cracked ribs, a fractured collar bone, severe whiplash. The doctor said he was lucky to be alive. Clint sat in the chair next to the bed. He’d been there for 6 hours.

Hadn’t left except to use the bathroom. When Bert finally opened his eyes, the first thing he saw was Clint holding a check. “What’s that?” Bert’s voice was raw. Clint held up the check. “It was made out to Bert Reynolds for $10,000.” “You made the jump,” Clint said. “You won the bet.” Bert stared at the check. Then he started laughing.

“It hurt like hell, but he couldn’t stop.” “You’re insane,” Bert said. “I almost died.” “You made it to the other side. Doesn’t matter how you landed. A bet’s a bet. Bert took the check, looked at it for a long moment, then slowly he tore it in half. I don’t want your money, Clint. What do you want? Bert met his eyes.

I want you to promise me something. Promise me we’re done competing. Promise me the next time I do something stupid, you’ll tell me I’m an idiot instead of betting money on it. Clint smiled. It was small, genuine. Deal. They sat in silence for a moment. You saved my life, Bert said quietly. You wouldn’t have needed saving if I hadn’t been so stupid.

No, I wouldn’t have needed saving if I hadn’t been so stupid. Bert shook his head. We’re a couple of dumb asses. Yeah, Clint agreed. We really are. The movie never got made. The studio shut down production after Bert’s accident. Too much liability, too much risk. The footage of the jump was locked away in a vault somewhere, never to be seen.

But the story spread through Hollywood like wildfire. Reynolds and Eastwood, The Bet, The Jump, The Rescue. Within a month, every actor in town knew about it. And the story changed something fundamental about how Hollywood worked. Studios began enforcing stricter safety protocols. Insurance companies got involved.

The era of actors doing insanely dangerous stunts for bragging rights began to end. But more than that, Bert and Clint’s friendship became legendary. They worked together three more times over the next decade. Every time they were on set together, crew members would watch them, looking for signs of that old competition, but it was gone, replaced by something better.

In 1985, during an interview, a reporter asked Clint about the canyon jump. “Biggest mistake of my life,” Clint said. “I almost killed a friend for my ego. I learned something that day. Being tough isn’t about doing dangerous things. It’s about knowing when to stop someone you care about from doing dangerous things.

And if you can’t stop them, you better be ready to catch them when they fall. Bert was asked the same question a week later. He smiled that famous smile. Clint saved my life that day. But the funny thing is, I saved his, too. We were both trapped in this stupid game of who’s tougher. That canyon forced us to realize something. We didn’t need to compete.

We were already friends. We just hadn’t admitted it yet. In 1995, Bert sent Clint a birthday present. Inside the box was the torn check from 1978, taped back together and a note that read, “Thanks for never cashing this, and thanks for being the kind of friend who pulls you out of the fire instead of watching you burn.

Happy birthday, you stubborn bastard.” Bert. Clint had it framed. It hung in his office until the day he died. Two men, one canyon, one stupid bet, and a friendship that proves sometimes the bravest thing you can do is admit you were

News

A 17-Year-Old Was Selling Her Father’s Piano for $80 — SUDDENLY Dean Martin Walked In

A 17-Year-Old Was Selling Her Father’s Piano for $80 — SUDDENLY Dean Martin Walked In My father played this every…

Why Lincoln Grew His Beard – The 11-Year-Old Girl Who Changed His Image

Why Lincoln Grew His Beard – The 11-Year-Old Girl Who Changed His Image October 15th, 1860, Westfield, New York. An…

How Did Churchill React When Patton Achieved in a Day What Others Couldn’t in Weeks?

How Did Churchill React When Patton Achieved in a Day What Others Couldn’t in Weeks? In the depths of March…

A Manager Tried to Remove John Wayne From a Restaurant — He Ended the Night a Legend

A Manager Tried to Remove John Wayne From a Restaurant — He Ended the Night a Legend The year was…

The Letter Roosevelt Wrote to Truman – So Insulting He Never Showed Anyone

The Letter Roosevelt Wrote to Truman – So Insulting He Never Showed Anyone April 12th, 1945. The time was 5:47…

Why Did Patton Assist a German General Following His Surrender?

Why Did Patton Assist a German General Following His Surrender? September 1944, Western France near the Lir River. A German…

End of content

No more pages to load