Cocaine Cowboys: A History of Coke in the Old Wild West…

The history of cocaine in America, particularly during the era of the Old West, is a tale of initial enthusiasm followed by growing concern and eventual prohibition. This powerful stimulant, derived from the coca plant, played a significant role in shaping American society, medicine, and law enforcement in the late 19th to early 20th centuries.

From its early popularity as a wonder drug and common ingredient in patent medicines, to its association with crime and racial tensions, cocaine’s journey through American history reflects the complex social, medical, and legal landscapes of a nation in transition. It’s vital that we explore the rise and fall of cocaine use in the United States, with a focus on its impact on the frontier culture of the Old West, examining how it went from being a widely available consumer product to a controlled substance within a relatively short span of time.

This is the story of cocaine on the American frontier. The cocaine alkaloid is derived from the Arithroxylon coca plant, a bush native to the Andean region of South America, including Peru, Bolivia, and Colombia. This plant has played a significant role in the cultures of these areas for millennia, with indigenous populations utilizing its leaves for their nutritional content and pharmacological effects, including the presence of cocaine.

In many Native South American societies, the practice of masticating coca leaves remains commonplace to this day. The Incan civilization, for instance, employed this method to combat the physiological challenges posed by high-altitude living. Consuming coca leaves aided in elevating their cardiovascular and respiratory rates, counteracting the effects of the rarefied air found at great elevations.

Archaeological discoveries have unearthed coca leaves among the possessions of ancient Peruvian mummies. Additionally, period ceramics depict individuals with distended cheeks, suggesting the widespread nature of coca leaf chewing. Some historical evidence points to the use of coca leaves combined with saliva as a primitive anesthetic during cranial procedures like trepanation, an early surgical technique involving the creation of holes in the skull to alleviate intracranial pressure or treat head trauma. Upon their arrival in South America, Spanish conquistadors initially

prohibited coca use, associating it with demonic influences. However, they soon recognized its role in maintaining worker productivity amongst the indigenous population. Consequently, they reversed their stance, legalizing coca and implementing a taxation system on its cultivation, claiming a portion of each harvest’s value for themselves.

In 1569, Nicolás Monardes, a Spanish botanist, documented the indigenous practice of mixing coca leaves with tobacco to induce a state of elation. He observed that this combination led to a sensation akin to inebriation and impaired judgment.

Four decades later, in 1609, Padre Blas Velera elaborated on coca’s therapeutic applications, noting its use in wound treatment, bone mending, and prevention of cold-related ailments. Valera posited that if coca could effectively treat external injuries, its internal consumption must yield even greater benefits. As Spanish settlers observed the near-constant presence of coca leaves in the mouths of indigenous individuals, many adopted the habit themselves.

Word of coca’s fatigue and hunger-suppressing properties eventually reached Europe. In the early 1800s, European researchers successfully isolated pure cocaine from coca leaves. This refined, crystalline form of cocaine proved to be significantly more potent, potentially hundreds of times stronger, than the traditional method of leaf chewing practiced by indigenous populations for centuries.

The energizing and hunger-reducing qualities of coca leaves had been recognized for generations, but it wasn’t until 1855 that researchers successfully extracted the key component, cocaine. Prior to this, numerous European chemists had attempted and failed to isolate the cocaine alkaloid. These difficulties stemmed from both the limited chemical knowledge of the era and the degradation of plant samples during lengthy sea voyages from South America to Europe.

However, a significant advancement occurred in 1855, when German chemist Friedrich Goethe became the first to extract the cocaine alkaloid. He dubbed it erythroxylene and published his findings in a prominent scientific journal in Germany. The following year, Friedrich Wühler, another German chemist, arranged for Dr.

Karl Scherzer, a scientist aboard the Austrian vessel Navarra, to procure a substantial quantity of coca leaves from South America. Three years later, upon completion of the ship’s global expedition, Vuhler received a chest filled with coca leaves. He then passed these specimens to Albert Nyman, a doctoral candidate at the University of Guttagen.

Nyman refined the extraction process, enhancing the ease of isolating and purifying the cocaine alkaloid. This breakthrough sparked considerable interest in Western medicine regarding the potential applications of cocaine. By 1879, another chemist from the University of Würzburg conducted experiments to showcase the substance’s analgesic effects. In one such trial, he submerged a frog’s limbs in two separate containers, one containing a cocaine solution and the other filled with ordinary salt water.

Upon stimulating both legs, he observed a marked difference in the reaction of the cocaine-treated limb, confirming its anesthetic properties. The drug also captured the attention of Karl Kohler, an associate of Sigmund Freud, who later wrote extensively about cocaine. In 1884, Kohler performed a notable self-experiment to evaluate cocaine’s potential in ocular surgery.

He applied a cocaine solution to his own eye and proceeded to probe it with needles, discovering that the drug effectively desensitized the area. Concurrently, other medical professionals explored the substance’s potential. In 1859, Italian physician Paolo Mantegazza returned from Peru, where he had witnessed indigenous people chewing coca leaves.

Back in Milan, Montagasa experimented with the drug himself and authored a paper lauding its effects. He believed that coca could be employed medicinally to address various ailments, including halitosis, flatulence, and even as a teeth whitener. One of the most significant commercial endeavors involving cocaine was initiated by chemist Angelo Mariani. Inspired by Montegazza’s work, Mariani sought to explore the economic potential of coca.

In 1863, he began marketing a wine infused with coca leaves, which became known as vin mariani, or coca wine. The alcohol in the wine functioned as a solvent, extracting cocaine from the cocoa leaves and imparting the beverage with its stimulating effects. Each ounce of the wine contained 6 mg of cocaine, but Mariani increased the concentration for the export to the United States, where similar concoctions were gaining popularity.

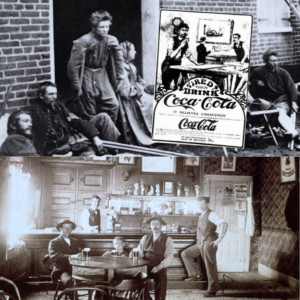

These cocaine-induced beverages were just beginning to appear in medicine cabinets and storefronts, right as United States populations expanded westward, across the American frontier, and right into the heyday of lawlessness of the Old West. In the late 19th century, cocaine found its initial foothold among laborers in the American frontier, where it was utilized as a stimulant.

Employers, operating under misguided notions, often supplied workers with cocaine, erroneously believing it would enhance their productivity. This practice was particularly prevalent among African-American workers, who were wrongly thought to derive greater benefits from the drug.

A racist misconception reported in medical news falsely claimed that cocaine rendered Black workers impervious to extreme temperatures. However, the substance’s reputation quickly soured. By 1897, Colorado pioneered legislation to regulate cocaine sales, largely due to concerns raised by the mining industry. The use of cocaine extended beyond African American laborers, gaining traction among workers of diverse backgrounds in northern urban centers.

Its popularity was partly due to its affordability compared to alcohol. In the Northeast, factory employees, textile mill workers, and railroad staff turned to cocaine to combat fatigue during extended shifts, sometimes using it as a caffeine substitute. Societal fears emerged about vulnerable groups, especially young women, being coerced into cocaine use with unfounded concerns that addiction would lead to prostitution.

While tales of youth corruption by cocaine circulated widely, concrete evidence supporting these claims was actually scarce. John Pemberton, a Civil War veteran, was among those who capitalized on cocaine’s rising popularity. Following a battle injury that led to morphine addiction, Pemberton sought an alternative treatment in cocaine.

Drawing inspiration from the success of Vin Mariani, the coca-infused wine, he developed his own concoction called Pemberton’s French Wine Coca. This product was marketed as a panacea for various ailments, and even touted as an aphrodisiac. However, the implementation of temperance laws in Georgia in 1885 forced Pemberton to reformulate his product. He substituted sugar for wine, creating a new beverage that would eventually evolve into Coca-Cola.

Following Pemberton’s death, Asa Griggs Candler assumed control of the company, marketing Coca-Cola as a patent medicine, a common practice at the time. The drink was promoted as a remedy for exhaustion and headaches. In 1898, faced with the proposed congressional attacks on medicines, Coca-Cola pivoted its marketing strategy, repositioning itself as a beverage rather than a medicinal product.

The name Coca-Cola reflected its primary ingredients,coca leaves and cola nuts. While the precise cocaine content in the original formula remains uncertain, it’s clear that early versions of the drink contained some amount of the drug. During this period, cocaine was still widely regarded as a popular stimulant, During this period, cocaine was still widely regarded as a popular stimulant, although concerns about its addictive properties began to surface by the late 1890s.

In the latter half of the 19th century, cocaine was readily accessible throughout the American frontier. It could be procured from a variety of sources, including pharmacies, taverns, general stores, and even mail-order catalogs.

Initially introduced in the 1860s as a potential solution for morphine dependency, cocaine quickly became a common, over-the-counter remedy for minor health issues. Soon after, it became a key ingredient in patent medicines, with cocaine-infused lozenges marketed as treatments for respiratory ailments and dental discomfort. Medical professionals prescribed it for a wide array of conditions, ranging from digestive issues and mood disorders to pain management and pregnancy-related nausea.

Cocaine was incorporated into various medicinal preparations such as cough mixtures, rectal suppositories, and topical applications. By 1885, cocaine was available in multiple forms, including cigarettes, powder, and injectable solutions. It gained popularity as a local anesthetic and medical procedures.

Promoted as a panacea for numerous ailments, from hemorrhoids to liver diseases, cocaine’s widespread use led to a nationwide health crisis. People consumed it in combination with chewing gum or tobacco, while soldiers utilized it to combat exhaustion. Itinerant merchants, often referred to as snake oil salesmen, traversed the frontier, peddling an array of cocaine-based products alongside other substances like opium, heroin, and morphine.

These traveling salesmen found a receptive market in frontier settlements, where their mobile pharmacies were stocked with questionable remedies. One of these snake oil salesmen’s favorite coked-up products was called Cocaine Candy. These sweet, hard candies were manufactured by Heater Halls, sold for five cents a tin, and included flavors such as kumquat, poppy, hemlock, mushroom, and spinach.

Their slogan? The sweet that stings. Get your kicks from lollipop licks. The candy that takes you on a trip. Not that cowboys on the frontier needed any more adventure. In 1885, the pharmaceutical giant Park Davis began mass-producing and distributing a variety of cocaine-based products, including coca leaf cigarettes, inhalants, cordials, crystalline cocaine, and injectable solutions.

The company’s bold marketing claimed its products could substitute for sustenance, instill courage in the timid, grant eloquence to the reticent, and render individuals impervious to pain. Cocaine’s influence became so pervasive that it even permeated popular literature by the late 1890s. In Arthur Conan Doyle’s detective stories, the iconic Sherlock Holmes was depicted as using cocaine injections to alleviate boredom between cases.

The drug’s popularity extended to early 20th century urban centers. In Memphis, Tennessee, cocaine was openly sold in Beale Street drugstores, with small quantities priced at just 5 or 10 cents. Laborers along the Mississippi River, particularly dock workers, used cocaine to maintain energy levels, and many Caucasian employers encouraged its use among African American workers as a productivity enhancer.

Cocaine even found its way into extreme exploration. During his 1909 Antarctic expedition, Ernest Shackleton included forced-march branded cocaine tablets in his supplies. The following year, Captain Robert Falcon Scott similarly equipped his ill-fated South Pole expedition with cocaine. By 1894, cocaine abuse epidemics were already making waves in the American West, with cities like Dallas, Texas among the first to experience significant issues.

Media coverage often portrayed cocaine use not just as a health concern, but as a societal menace, particularly when associated with African American and working class communities. The aforementioned depiction of cocaine use among Black populations was heavily influenced by racial biases, with Southern urban centers especially promoting fears of rampant drug use within African American communities.

This growing alarm prompted state legislatures more eastward—in Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee—to propose their first anti-cocaine laws by 1900. Exaggerated and sensationalized accounts of cocaine’s effects on African Americans also fueled widespread panic. In 1901, the Atlanta Constitution reported an alleged dramatic increase in cocaine use among Black individuals.

The New York Times followed with an article claiming cocaine enhanced sexual urges and transformed peaceful Black people into aggressive, violent individuals.Some medical professionals even asserted that cocaine drove African Americans to criminal behavior, including sexual assault, further intensifying public fears.

One Mississippi judge went as far as to claim that giving cocaine to a Black person was more perilous than infecting a canine with rabies. These extremely racist viewpoints shaped drug policies, law enforcement strategies, and incited violence against African Americans. In 1906, a major racial conflict erupted, instigated by white citizens responding to reports of black cocaine fiends engaging in criminal activities.

Such white-led racial violence, fueled by exaggerated fears of black cocaine users, was not uncommon during this era. Southern police forces began using higher-caliber firearms, believing that Black individuals under the influence of cocaine possessed superhuman strength.

A dangerous myth also circulated that cocaine granted African Americans exceptional marksmanship, leading some officers to adopt aggressive tactics in confrontations. leadership, leading some officers to adopt aggressive tactics in confrontations. Public sentiment soon turned decisively against cocaine users, with criminal behavior becoming closely linked to cocaine use, especially amongst Black individuals.

Sensationalized news reports of violent incidents involving cocaine further cemented the stereotype of the dangerous, violent, cocaine-crazed user, a stereotype deeply rooted in racial prejudice. Prior to federal government intervention with comprehensive cocaine regulations, individual states and cities implemented their own measures.

Early enforcement often relied on public nuisance laws, such as those addressing vagrancy or disorderly conduct. In the absence of nationwide legislation specifically targeting cocaine, law enforcement had to be inventive in controlling its use and distribution. Rather than focusing on production, authorities primarily targeted distributors, such as pharmacies.

on production, authorities primarily targeted distributors, such as pharmacies. In many instances, local health boards or pharmacy regulators assumed oversight rules for cocaine sales. Some states opted for complete prohibition of cocaine. Georgia led the way in 1902, becoming the first state to implement a total ban on cocaine sales.

Other states, like Louisiana, enacted ordinances restricting sales but maintained vague exceptions for medicinal uses. Most states, however, chose stricter controls over outright bans. For example, California passed a law in 1907 mandating that cocaine only be sold with a physician’s prescription, resulting in over 50 arrests of store owners and clerks within the first year. New York followed suit in 1913, limiting druggists’ cocaine stock to under 5 ounces.

Early labeling requirements also emerged, with some states mandating that products containing cocaine be clearly marked as poisonous. The declining reputation of cocaine became evident through its impact on notable figures such as William Halstead, a trailblazer in modern American surgical practices. Despite his considerable medical achievements, Halsted’s ongoing battle with addiction underscored the perilous nature of cocaine use.

Once lauded for its invigorating properties, cocaine was increasingly associated with severe dependency and cognitive decline. Similarly, Sigmund Freud’s experience with the drug served as another cautionary tale. with the drug served as another cautionary tale.

Initially an advocate for cocaine as a remedy for mental health issues, Freud’s enthusiasm waned as he encountered alarming side effects, including epistaxis and cardiac arrhythmias, ultimately leading him to retract his earlier endorsement. As instances of addiction proliferated, cocaine’s standing in society deteriorated. Public opinion shifted dramatically, and apprehension about the drug’s hazards intensified, prompting congressional action towards regulation.

This culminated in the enactment of the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act in 1914. Tax Act in 1914. This landmark legislation sought to regulate and impose taxes on the importation, production, and distribution of opiate and coca-derived products. The act served a dual purpose, addressing the escalating addiction crisis and mending international relations with China by clamping down on illicit opium trade.

relations with China by clamping down on illicit opium trade. While some states initially resisted the federal statute, viewing it as an encroachment on their autonomy, widespread fear of the cocaine fiend phenomenon facilitated its passage. Various societal influencers, including the press, political figures, and medical professionals, amplified the panic by emphasizing the drug’s purported dangers, often exploiting racial and socioeconomic anxieties.

The Harrison Act stands as one of the earliest instances of nationwide drug control in the United States.Following the Act’s implementation, cocaine swiftly receded from public discourse. Its legal status severely curtailed. The once popular stimulant faded into obscurity. The conclusion of cocaine’s brief era of widespread acceptance coincided with the end of the old frontier period in American history.

News

Why Sherman Begged Grant Not to Go to Washington

Why Sherman Begged Grant Not to Go to Washington March 1864. The Bernett House, Cincinnati, Ohio. Outside the city is…

What Patton’s CRAZY Daily Life Was Really Like on the Front Lines

What Patton’s CRAZY Daily Life Was Really Like on the Front Lines General George Patton believed war was chaos and…

Joe Frazier Was WINNING vs Ali in Manila — Then His Trainer Said “Sit Down, Son

Joe Frazier Was WINNING vs Ali in Manila — Then His Trainer Said “Sit Down, Son Manila, October 1st, 1975….

Frank Sinatra Ignored John Gotti at a Hollywood Diner—By Nightfall, Sinatra Wasn’t Smiling

Frank Sinatra Ignored John Gotti at a Hollywood Diner—By Nightfall, Sinatra Wasn’t Smiling Beverly Hills, California. February 14th, 1986. The…

Clint Eastwood’s Racist Insult to Muhammad Ali — What Happened Next Silenced Everyone

Clint Eastwood’s Racist Insult to Muhammad Ali — What Happened Next Silenced Everyone Los Angeles, California. The Beverly Hilton Hotel…

Brad Stevens Insulted John Wayne’s Acting—What Happened Next Changed His Life Forever

Brad Stevens Insulted John Wayne’s Acting—What Happened Next Changed His Life Forever Universal Studios Hollywood, August 15th, 1964. A tense…

End of content

No more pages to load