Conductor Told Johnny Cash “This Hall Is for Real Musicians” — Then Cash Picked Up a Microphone

March 14th, 1992. Carnegie Hall, New York City. Stern Auditorium was glowing that evening, its cream and gold walls catching the light of 3,000 crystal bulbs as Manhattan’s classical music elite gathered for the American Arts Foundation’s annual charity gala. Ticket prices started at $2,000.

The guest list read like a registry of old money and inherited taste. conductors, soloists, patrons, and the kind of wealth that never needed to announce itself. But nobody in that auditorium knew that in exactly 23 minutes, a man from Kingsland, Arkansas, a man most of them had already written off, would deliver a performance that not a single one of them would ever forget.

When Johnny Cash walked through the oak panled doors, the first thing he noticed wasn’t the grandeur. It was the way people looked at him and then looked away. He was 60 years old, tall and gaunt in his signature all black suit, his hair dark but threaded with silver, his face carved deep with lines that told stories no symphony could carry.

June was beside him, her arm through his, wearing a simple black dress and the quiet kind of grace that didn’t need diamonds to prove anything. They were there because a friend of a friend had extended an invitation. Cash had almost said no. By 1992, Nashville had all but erased him. His record label had dropped him two years earlier.

Radio stations had quietly removed his songs from rotation. The man who once packed stadiums was playing state fairs and half empty auditoriums, and the industry’s verdict was clear. Johnny Cash was finished. But June had said yes for both of them. John, she told him that morning, pressing his black shirt with steady hands.

We’re not going because they invited us. We’re going because music doesn’t belong to people who think they own it. At the center of the reception hall, Maestro Victor Kesler held court with the practiced ease of a man who had spent 40 years being told he was extraordinary. Kesler was 63, Germanborn, silver-haired with a conductor’s posture that made him appear taller than his 5’9.

He had led the Berlin Filarmonic for a decade. Guest conducted at Vienna, at the Met, at every major hall in Europe. His voice was sharp, his opinions were sharper, and his contempt for anything outside the classical cannon was legendary. He’d once dismissed American popular music as organized sentimentality in a New York Times interview, and the quote had only deepened his admirer’s devotion.

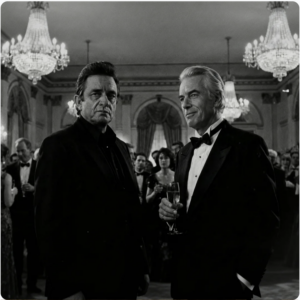

But nobody yet knew that this man’s arrogance was about to collide with something it had never encountered. The kind of truth that doesn’t need a conservatory education to cut straight through you. Kesler was midway through an anecdote when his gaze landed on cash. The conductor paused, champagne glass suspended between chest and lips.

Something shifted in his face, amusement and the particular satisfaction of a man who has just spotted easy prey. Cash and June had nearly reached the bar when Kesler’s voice cut across the room. “Well,” he said, projecting effortlessly, “it appears Carnegie Hall has expanded its definition of musician this evening.” Several people laughed.

Cash’s expression didn’t change. He’d been hearing this his whole life. Kesler separated from his circle and approached them. Champagne in one hand, the other tucked behind his back. “Mr. Cash, isn’t it?” he said, his accent lending sophistication to what was underneath plain cruelty. “What an unexpected pleasure! I wasn’t aware the foundation had branched into folk entertainment.

” Cash picked up a glass of water. He hadn’t touched alcohol in years. And took a slow sip. “Evening,” he said. That was all. His voice was low, unhurried. That deep Arkansas bass that sounded like a freight train heard from a long way off. “June stepped in with the warmth that had diffused a thousand such moments.

” “Maestro Kesler, we heard your Brahms recording last season. Truly beautiful.” Kesler accepted the compliment, but his eyes never left Cash. Brahms. Yes. Music that demands decades of training to perform, let alone appreciate. Layers, nuance, structure, things that perhaps don’t translate to three chords and a train rhythm.

The circle of onlookers had grown. Cash set his glass on the bar and looked at Kesler directly without flinching. I reckon three chords is plenty, he said. If you’ve got something real to say with them. Kesler’s smile remained, but something shifted behind it. He wasn’t used to being answered back with that kind of granite calm. Come now, Mr. Cash.

Surely you appreciate the difference between what we do here and what you do in your venues. Classical music is the language of civilization. Country music is perfectly adequate for what it is. He looked around, making sure everyone was listening. Simple music for simple feelings. The air grew heavy.

June took a half step forward, but Cash touched her arm, gently, barely visible. She knew that touch. After 30 years, she could read it the way a sailor reads weather. It meant he had this. It meant something was stirring behind those dark, quiet eyes. But what nobody expected was what Kesler did next. The conductor turned to the crowd, voice caring. In fact, I have a thought.

Tonight’s program features the finest classical musicians in New York. But perhaps in the spirit of cultural exchange, we might invite Mr. Cash to give us a performance. He turned back to Johnny with exaggerated warmth. One song just for fun. My orchestra can provide accompaniment if you can manage to stay in key.

The laughter was thin and nervous. The trap was obvious. Kesler expected Cash to refuse and look diminished or accept and humiliate himself in a hall built for Beethoven. Either way, the conductor would win. June leaned into her husband’s ear. John, let’s leave. We don’t need this. Her whisper carried the fierce protectiveness of a woman who had spent decades standing between this man and everything that tried to break him.

The pills, the industry, the silence. Cash didn’t answer right away. He looked at Kesler. He looked past him through the auditorium doors where rows of crimson velvet waited in the half light and a grand Steinway gleamed at center stage like a black lake. He thought about the state fairs and the empty seats and every voice that had spent three years telling him he was done.

Then he looked at June and she saw it. That expression she’d seen in prison cafeterias and recording studios and on stages from Folsam to San Quentin. The look that said Johnny Cash had made up his mind and nothing on earth was going to change it. All right, Cash said. His voice didn’t rise. It didn’t need to. Where’s the stage? Two words.

The smirk on Kesler’s face held, but something behind it stumbled. He had expected hesitation. not this granite certainty from a man the whole industry had written off. June closed her eyes for a moment, squeezed her husband’s hand, and let go. She didn’t try to stop him. She never could when he got this way, and deep down she didn’t want to because June Carter Cash knew something that Victor Kesler did not.

She knew what this man could do with nothing but a song and a broken heart. The event organizer appeared at Cash’s side, pale and panicking. This wasn’t in the program, but June whispered something in the woman’s ear, and after a long pause, she nodded. Cash straightened his black jacket and turned toward the stage. The crowd parted. Nobody knew what was about to happen, but in exactly 4 minutes, 2800 people were going to find out what Johnny Cash sounded like when he had something to prove.

Not to them, not to Victor Kesler, but to himself. Cash walked slowly toward the stage, and the crowd parted like water around a black stone. June stayed at the edge of the reception hall, hands clasped, knuckles white. She had watched this man walk into Fulsome prison and turn a thousand convicts into a congregation.

But she had never watched him walk into a room where every single person expected him to fail. Kesler had taken his position in the front row, legs crossed, arms folded, the posture of a man settling in to watch a verdict he had already delivered. Cash climbed the four steps to the stage. His knees achd, but his back was straight and his shoulders were set the way they’d been since he was a boy picking cotton in Dice, Arkansas.

He crossed to the Grand Steinway, where the accompanist sat waiting. Cash leaned down and spoke quietly. Her eyes widened, but after a moment she nodded. In the orchestra pit, two dozen musicians exchanged looks. There was no sheet music for whatever was about to happen. Cash stood at center stage and looked out at 2800 faces.

He didn’t take a microphone. Carnegie Hall was built for unamplified sound. and Cash understood acoustics the way he understood most things, not through theory, but through decades of standing in rooms and listening to how they breathed. Then he spoke. His voice filled the hall without effort, the way water fills a glass.

I didn’t go to conservatory, he said. Everyone here knows that. I grew up on a cotton farm in Arkansas. My family didn’t have a piano. We didn’t have much of anything. He paused, his eyes drifting to a point somewhere above the back rows. But we had hymns. My mother sang them in the fields.

My brother Jack sang them on the porch in the evenings. Jack wanted to be a preacher. He was the good one in the family. Another pause, longer this time. The auditorium had gone completely still. When I was 12 years old, Jack was pulled into a table saw at the mill where he worked. He was 14. They carried him home, and he lay dying for 3 days, and there was nothing anyone could do.

Cash’s voice didn’t break. It stayed low and steady, but there was a weight in it that pressed against the walls of that magnificent room, like something physical. On the last night, Jack started singing hymns, the same ones our mother sang in the fields. He sang until he couldn’t sing anymore, and then he was gone.

Not a single sound from the audience. Kesler had uncrossed his arms. Cash looked at the pianist and nodded. She placed her fingers on the keys and played the first four notes. Soft, simple, a melody that threearters of the room recognized before the second measure, not because they had studied it, but because it lived in a place deeper than study.

Amazing grace, the chist in the pit picked up his bow without being asked. Then the first violinist. Then the second. One by one, the orchestra began to join. No conductor, no score, just musicians following the oldest instinct of their craft, the instinct to listen and respond. Cash closed his eyes and began to sing.

That voice deep as a mineshaft, rough as unfinished wood, and so full of lived truth that it made the polished perfection of everything else performed that evening sound like beautiful lies. He didn’t sing it the way a trained vocalist would. There was no VB control, no careful placement. But there was a boy kneeling beside his brother’s bed in a clabbered house in Arkansas.

There was a man who had swallowed pills until they nearly swallowed him. There was a prisoner of his own fame who had walked into actual prisons and found the only audiences that ever made him feel free. Every year of it was in that voice. the loss, the shame, the faith that wouldn’t stay dead no matter how many times he tried to kill it.

When Cash reached the second verse, something extraordinary happened. A woman in the third row stood up. Then a man near the aisle, then an elderly couple in the mezzanine. One by one, the audience rose, not applauding, not cheering, and just standing. The way people stand in church when they feel something holy moving through the room.

Cash sang the final verse alone. The orchestra had gone silent, the pianist’s hands resting motionless on the keys. His unaccompanied voice filled Carnegie Hall the way candle light fills a cathedral, not by overpowering the darkness, but by making it irrelevant. The last note hung in the air. Then it faded, and the silence that replaced it was not empty.

It was the silence of 2,800 people who had just been reminded that music doesn’t come from training or technique. It comes from the part of a person that has been broken open enough to let the truth out. 3 seconds, 5 seconds, then the applause. Not polite classical applause, but the raw full-bodied sound of people clapping because their hands were moving before their minds caught up.

2,800 people on their feet, some wiping their eyes, some looking at strangers with the bewildered intimacy of people who have shared something they didn’t expect. June stood at the edge of the hall, both hands over her mouth, tears running down her face. She had heard Johnny sing that hymn a thousand times, but never in a room that had tried to make him small, and watched him become the largest thing in it.

Kesler rose from his seat. He stood still for a moment. Then he did something no one in his circle had ever seen him do. He walked to the stage, climbed the steps, and stood before Cash. Conservatory and Cotton Field, theory and truth. Kesler extended his hand. I owe you an apology, he said quietly.

But Carnegie Hall’s acoustics carried every syllable. I was arrogant and I was wrong. Cass shook the man’s hand. We all get it wrong sometimes. What matters is what you do after. As they walked off stage, Cash leaned close to June’s ear. Jack would have liked that. June squeezed his arm. Jack heard it, John. I promise you, he heard it.

3 weeks later, a short piece appeared in the New York Times arts section. The headline read, “Cash silences Carnegie.” The final paragraph abandoned the critic’s usual restraint. In a hall that has hosted the greatest voices in western music, it was a 60-year-old man from Arkansas singing an 18th century hymn who reminded us why any of it matters.

But the real story happened two years later. Victor Kesler, interviewed by a German magazine, was asked to name the greatest performance he had witnessed in 40 years of conducting. He was quiet for a long time. Carnegie Hall, 1992. He said, “A man I had insulted stood on a stage with no orchestra, no score, no training, and sang a hymn.

And I understood that everything I knew about music was only half the truth.” The interviewer pressed him. “What was the other half?” Kesler smiled, a real smile, not the practiced one. “Suffering,” he said. “You can’t learn that at a conservatory.” Years later, June spoke about that evening. I was scared when John walked up those steps.

But then I remembered this is a man who sang for prisoners and presidents who buried his brother at 12 and carried that grief into every song he ever sang. Was a room full of fancy people going to frighten him. She paused. Johnny didn’t have a degree. He had the truth. And that night the truth was enough. Johnny Cash was not a classical musician.

But that night, he reminded 2800 people of the oldest lesson in music. That a song sung from a broken heart will always reach further than perfection ever could. Amazing Grace was written in 1772 by a slave trader who found redemption. Cash sang it in 1992 as a man the world had given up on. And both proved the same thing, that grace doesn’t ask for your credentials.

It only asks whether you’ve been lost enough to know what it means to be found.

News

A Contractor Used Cheap Brick on Gambino’s House — His Construction Fleet Was Blown Up at Noon

A Contractor Used Cheap Brick on Gambino’s House — His Construction Fleet Was Blown Up at Noon Tommy Brush’s hands…

A Gambler Lost Big to Carlo Gambino and Refused to Pay — He Was Dragged Out in the Parking Lot

A Gambler Lost Big to Carlo Gambino and Refused to Pay — He Was Dragged Out in the Parking Lot …

What Grant Thought The Moment He Heard Lincoln Was Dead

What Grant Thought The Moment He Heard Lincoln Was Dead It is the middle of the night, April 14th, 1865….

The Moment Eisenhower Finally Had Enough of Montgomery’s Demands

The Moment Eisenhower Finally Had Enough of Montgomery’s Demands December 29th, 1944. The Supreme Commander of all Allied forces in…

Thieves Robbed Tony Accardo’s House — He Didn’t Call The Police, He Left Their Bodies Stu…

Thieves Robbed Tony Accardo’s House — He Didn’t Call The Police, He Left Their Bodies Stu… The date is January…

Champion Picked A Man From The Crowd — Realized It Was Bruce Lee — Then Challenged Him Anyway

Champion Picked A Man From The Crowd — Realized It Was Bruce Lee — Then Challenged Him Anyway Long Beach,…

End of content

No more pages to load