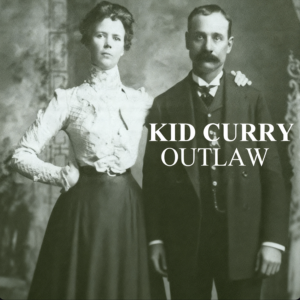

Did Kid Curry Really Die in 1904? The Wild Bunch’s Darkest Mystery

In June of 1904, a body lay on a table in Glenwood Springs, Colorado. The man had been shot during a posi chase, then put a bullet in his own head rather than face capture. Local authorities looked at the corpse and declared it was Harvey Logan, better known as Kid Curry, the Wild Bunch’s most dangerous gunman.

The newspapers ran with the story. Front pages across the West announced the death of one of America’s most wanted outlaws. But here’s where things get strange. Years after that body was buried, a Pinkerton detective named Charlie Seringo, who’d spent years hunting the Wild Bunch, walked away from the agency convinced of one thing.

They’d buried the wrong man. If the Pinkertons themselves didn’t believe the body in that Colorado grave was Kid Curry, should we? Before we dig into whether Kid Curry actually died that day, let’s talk about why this question still matters over a century later. Harvey Logan wasn’t some small-time bandit who knocked over a general store and called it a career.

The Pinkerton Detective Agency called him the most dangerous outlaw in America. That’s not newspaper hyperbole. That’s what the men who hunted him professionally believed. By the time that body showed up in Glennwood Springs, Curry had allegedly killed at least nine lawmen in five separate shootouts. He’d robbed banks and trains from Montana to New Mexico.

And unlike his more famous partners, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, who reportedly never killed anyone during their robberies, Kid Curry had a reputation for pulling the trigger when things went wrong. If anyone in the Wild Bunch had the skills, the nerve, and the sheer ruthlessness to fake his own death and disappear, it was Harvey Logan.

Today, we’re going to walk through the evidence, and there’s more of it than you might expect. We’ll look at the official story of that shootout near Parachute, Colorado. We’ll examine the identification that convinced most people the dead man was Curry. Then we’ll dig into why a veteran Pinkerton detective walked away from his career rather than accept that conclusion.

We’ll talk about the physical evidence that didn’t quite add up, the rumored sightings that came later, and the fact that even the Pinkerton agency itself seemed to change its mind about whether they’d really gotten their man. By the end, you’ll have all the pieces to decide for yourself whether Harvey Logan died in 1904 or whether the West’s deadliest outlaw pulled off one final con.

To understand what happened in Colorado in 1904, you need to know who Harvey Logan was and how he ended up there. He was born in 1867 in Iowa, but his childhood was rough from the start. His mother died when he was 9 years old. Harvey and his brothers ended up in Missouri with relatives. But by his teenage years, Harvey was already drifting.

He worked as a cowboy in Texas, breaking horses on ranches, and that’s where he met a man named George Curry, who went by the nickname Flatnse. Harvey took George’s last name as his own, becoming Harvey Curry. His brothers followed suit. It was common enough in the West for men to change their names, but in Harvey’s case, it marked the beginning of a transformation from cowboy to outlaw.

The trouble started in Montana in 1894. Harvey got into a confrontation with a local tough named Pike Landuski over a woman. Some accounts say it was Landusky’s stepdaughter. Others say it was Harvey’s brother who was involved with her. Either way, Landuski beat Harvey badly and filed assault charges. Harvey was arrested and roughed up by local law enforcement who were friendly with Landuski.

A few weeks later, Harvey caught Landuski in a saloon. The two men fought and when Landuski drew his gun, Harvey borrowed a pistol from a friend and shot Landuski dead. An inquest ruled it self-defense, but a trial was scheduled and Harvey didn’t trust the judge to give him a fair shake, so he ran. That decision changed everything. Harvey started riding with Outlaws.

First with Tom Blackjack Ketchum’s gang, then eventually with the Wild Bunch. In January 1896, Harvey learned that rancher James Winters, a friend of Landuskies, had been spying on him for the reward. Harvey and two of his brothers, Johnny and Lonnie, went to confront Winters. A shootout erupted and Johnny was killed.

Harvey and Lonnie escaped, but that death would haunt Harvey for 5 years. By 1899, he was part of the crew that pulled off the famous Willox train robbery in Wyoming, one of the biggest heists of the era. The Pinkerton Detective Agency, put their best men on the case. That’s when Charlie Seringo, one of their top operatives, started tracking Harvey Logan.

Between 1896 and 1904, Kid Curry’s reputation grew darker. His brother Lonnie was killed by law men in February 1900. In May of that same year, Harvey traveled to Utah and killed Grand County Sheriff Jesse Tyler and his deputy in a gunfight in Moab. Reportedly, both killings were in retaliation for their role in killinghis friend George Curry and his brother Lonnie.

Then, in July 1901, Harvey finally settled his score with James Winters. He waited outside Winter’s cabin and shot him in cold blood 5 years after Winters killed Johnny Logan. The pattern was clear. Harvey Logan didn’t forget and he didn’t forgive. By late 1901, Harvey’s luck was running out. His girlfriend, Dela Moore, who also went by Annie Rogers, was arrested in Nashville for passing stolen banknotes.

On December 13th, 1901, Harvey got into a fight in a Knoxville pool hall and shot two policemen, William Dwitt and Robert Sailor, when they tried to arrest him. He escaped but was captured two days later near Jefferson City and brought back to Knoxville, beaten and bloodied. Harvey spent a year and a half in the Knox County Jail where he became something of a celebrity.

Thousands of people, mostly women, visited him in jail. On November 21st, 1902, after hearing testimony from 34 witnesses, he was convicted on 10 counts of counterfeiting, forging, and passing stolen banknotes. He was sentenced to 20 years of hard labor, and a $5,000 fine. But on June 27th, 1903, Harvey Logan pulled off one of the most daring jail escapes of the era.

Using wire from a broom, he fashioned a lasso and looped it around a guard’s neck. He retrieved guns that had been hidden in the jail, forced the jailer to let him out, and rode away on Sheriff Fox’s horse. He was last seen galloping across the Gay Street Bridge. Rumors swirled that a deputy had been bribed $8,000 to let him escape, but nothing was ever proved.

After that escape, Harvey Logan vanished for nearly a year. When he resurfaced, it was for one last job near Parachute, Colorado. Here’s what we know happened. On June 7th, 1904, three men robbed a Denver and Rio Grand train west of Parachute. They used dynamite to blow open the express car safe, grabbed what money they could find, then escaped into the rainy night.

They rode across the Colorado River in a small boat, and picked up horses waiting on the other side. So far, it was a fairly standard train robbery for the era. But they made a mistake. On June 9, 2 days after the robbery, the three outlaws stopped at the Banter Ranch on Divide Creek.

They demanded breakfast and fresh horses. Mrs. Bant had something the outlaws didn’t expect, a telephone. As soon as they left, she started calling neighbors, and word spread fast. A posy of about 40 men assembled, pulling ranchers and lawmen from towns across the area. Later that same day, the posi caught up with the three bandits near Garfield Creek, south of Newcastle.

A shootout erupted. According to the reports, the outlaws shot the horses out from under two of the pursuers. A rancher named Rola Gardner and his neighbor. The neighbor started running for cover. One of the bandits took aim at him. That’s when Gardner, who’d found a good position, fired his rifle. The bullet hit one of the outlaws.

The man’s two companions urged him to escape through the gulch. But reportedly, the wounded outlaw said something like, “Don’t wait for me. I’m all in and might as well end it right here.” He raised his revolver to his temple and pulled the trigger. The other two bandits disappeared into the Colorado wilderness and were never identified or caught.

The dead man’s body was brought to Glenwood Springs. He was photographed, and that’s important because those post-mortem photos would become key evidence in the debate over his identity. The body was buried in the Pottersfield section of Lynwood Cemetery under the name JH Ross, which was reportedly an alias the dead man had been using to work on a railroad crew.

Now, here’s where the identification process began, and it’s worth paying attention to the details because they matter. The Pinkerton Detective Agency sent Lel Spence, one of their operatives who had been tracking Kid Curry, to examine the photographs. Spence looked at the death photos and declared that the dead man was Harvey Logan, alias Kid Curry.

To back up his identification, Spence requested that the body be exumed so a doctor could examine it for identifying marks. A physician named Dr. M. Alistister performed the examination. His report is interesting for what he focused on. He noted the man’s general appearance and even made a strange observation about the corpse’s moral character based on his facial features, which was a common pseudocientific practice of the era.

More importantly, he looked for scars and distinguishing marks. Spence took copies of the post-mortem photos to Knoxville, Tennessee, where Curry had spent over a year in jail. Several lawmen and attorneys who had known Curry during his time there looked at the photos and reportedly identified them as depicting Harvey Logan.

The newspapers got hold of the story. On July 12th, 1904, the St. Paul Daily Pioneer Press ran the news along with four of the post-mortem photos. For most people, that settled it. Kid Curry was dead. But not everyonewas convinced and the doubts started almost immediately. Here’s the first problem. Harvey Logan had been shot in the right wrist during an earlier robbery near Bell Forge, South Dakota in 1897. That wound left a scar. When Dr.

McAllister examined the body about a month after the robbery, he reported finding no scar on the wrist. That’s a significant discrepancy. You don’t lose a gunshot scar. The second issue involved more subtle details. David Bailey, who later became curator of history at the Museums of Western Colorado, studied photographs of both Harvey Logan and the dead man from Parachute.

He noted differences in the ears and other facial features. Photography in 1904 wasn’t great, especially post-mortem photography, but Bailey believed the differences were significant enough to question whether the two men were the same person. Then there’s the matter of general identification practices at the time. There were no fingerprints on file.

There was no DNA testing. The identification came down to visual recognition by people who knew Curry, examination of the body for scars, and comparing the dead man’s possessions to what Curry might have carried. One of the confirming details was reportedly a 3-in scar on the top of the dead man’s head, which matched an injury Curry had received from a nightstick wielding Knoxville policeman during his capture.

But even that wasn’t a certainty. Other men could have had similar scars. The truth is, identification in 1904 was part science, part guesswork, and a lot of hoping you got it right. If a dead man had the right gun, the right clothes, and a couple of physical features that seemed to match, authorities often called it good enough.

But good enough for a newspaper headline isn’t the same as beyond a reasonable doubt for a criminal conviction. And that’s where Charlie Seringo’s doubts come in. Charlie Seringo wasn’t some rookie detective making wild guesses. By 1904, he’d been with the Pinkerton Agency for nearly 20 years. He’d worked undercover, infiltrated outlaw gangs and tracked suspects across tens of thousands of miles.

When the Union Pacific train robbery happened at Willox, Wyoming in 1899, it was Seringo who spent four years chasing the Wild Bunch across the West. He interviewed witnesses, followed leads from Montana to New Mexico, and got close enough to the gang to understand how they operated. When it came to knowing the faces and methods of Butch Cassid’s crew, few lawmen had more experience than Charlie Seringo.

So when Seringo read the reports that Kid Curry had been killed in Colorado in 1904, he didn’t buy it. We know this because Seringo later wrote about his experiences, though the Pinkerton agency sued him repeatedly to keep him from publishing details. What’s documented is that Singingo refused to believe the body from Parachute was Harvey Logan.

Ultimately, his doubts contributed to his decision to resign from the Pinkertons in 1907. Think about that. A man doesn’t walk away from a successful 20-year career over nothing. Seringo was willing to put his conviction on the line, and his conviction was that they’ buried the wrong man. Why would Seringo doubt the identification? We can speculate based on what we know.

First, Seringo had physically tracked members of the Wild Bunch during his investigations. He’d studied their methods, tracked their movements, and interviewed people who knew them. If the physical description or behavior patterns of the dead man didn’t match what Seringo knew about Curry, that would raise flags.

Second, Seringo understood how outlaws operated. The Wild Bunch had a track record of using aliases, switching identities, and disappearing when the heat was on. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were already rumored to have fled to South America. Why couldn’t Harvey Logan have done something similar? What makes Sedrango’s doubts particularly interesting is that he wasn’t alone in his skepticism, at least not within the Pinkerton agency.

In December 1905, over a year after the supposed death of Kid Curry, a bank was robbed in Argentina. The Pinkerton agency sent wanted posters to police and newspapers in Argentina. Those posters identified the suspects as Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid, Ed Place, and Harvey Logan. That’s right. The same agency that had officially declared Curry dead in July 1904 was circulating his wanted poster in South America in December 1905.

You don’t send out wanted posters for dead men unless you think they might not be dead. And there were the rumors. Stories circulated for years about Kid Curry being spotted in various places. Some claimed he’d gone to South America and reunited with Butch and Sundance. Others said he’d taken a new identity somewhere in the American West.

In November 1904, just months after the parachute incident, a bank in Cody, Wyoming was robbed in the cashier killed. Local officials swore the leader of the gang was Kid Curry. Buffalo Bill Cody himself reportedly led a posi afterthe robbers, though they escaped. Were these sightings credible? That’s hard to say.

People see what they expect to see, and Kid Curry had become almost mythical by 1904. Every bandit with a temper and a decent aim probably got tagged as Kid Curry at some point. But the sheer number of reports combined with the Pinkerton AY’s own uncertainty kept the question alive. Was Harvey Logan really in that grave in Glennwood Springs. Let’s be clear about something.

Most historians who’ve studied this case believe the man killed near Parachute in 1904 was Harvey Logan. The evidence, while not perfect, points in that direction more strongly than any alternative. The physical description was close enough. The behavior shooting himself rather than being taken alive matched what people knew about Curry’s personality.

The Knoxville lawman who identified the photos had spent time with Curry and had no obvious reason to lie. And the 3-in scar on the head, if accurately documented, was a strong identifying mark. The absence of the wrist scar is harder to explain away, but there are possibilities. Maybe Dr. Mick Alistister didn’t look carefully enough.

Maybe the scar had faded more than expected. Maybe it was on the other wrist and records got it wrong. Medical examinations in 1904 weren’t conducted with the rigor we’d expect today. Mistakes happened. As for the Pinkerton agencies flip-flopping, that could have been internal politics, financial considerations about rewards, or genuine uncertainty based on conflicting reports, large organizations don’t always speak with one voice, especially when dealing with incomplete information.

But here’s what makes this story compelling. Even if you believe Curry died in 1904, we’ll never know for absolute certain. The body was buried without a proper autopsy by modern standards. The identification relied on methods that we’d consider unreliable today. The photographs, while helpful, weren’t conclusive.

And in a time without fingerprints, without DNA, without dental records, or any of the forensic tools we take for granted now, even a 95% certainty leaves room for doubt. That 5% of uncertainty is where legends live. It’s where men like Harvey Logan can become ghosts riding off into the frontier one more time, disappearing into myth rather than dying in a Colorado gulch with a posi closing in.

The West was changing in 1904. The frontier was closing. The railroads and telegraphs and telephones were making it harder for outlaws to vanish into empty spaces. Kid Curry’s death, whether real or staged, marked the end of an era. And maybe that’s why the question still matters.

Did Kid Curry die in 1904? Probably. The evidence leans that way. But in a world without modern forensics, where a man’s identity could be as fluid as the aliases he used, where the Pinkerton Detective Agency itself couldn’t agree on the answer, and where a veteran lawman like Charlie Seringo walked away from his career convinced they’ buried the wrong man.

The ghost of reasonable doubt still haunts that grave in Glenwood Springs. So, what’s your verdict? dead in Colorado, shot by a posi and buried under a marker that may or may not bear his real name, or a ghost of the frontier. One last outlaw who slipped through the net and rode south while everyone else was looking at a body on a table.

Let me know in the comments what you think. And while you’re down there, tell me which Wild West mystery you want me to tackle next. If you’re enjoying these deep dives into the stories that don’t have easy answers, hit that subscribe button. There are plenty more mysteries where this one came from.

News

What Patton’s CRAZY Daily Life Was Really Like on the Front Lines

What Patton’s CRAZY Daily Life Was Really Like on the Front Lines General George Patton believed war was chaos and…

Joe Frazier Was WINNING vs Ali in Manila — Then His Trainer Said “Sit Down, Son

Joe Frazier Was WINNING vs Ali in Manila — Then His Trainer Said “Sit Down, Son Manila, October 1st, 1975….

Frank Sinatra Ignored John Gotti at a Hollywood Diner—By Nightfall, Sinatra Wasn’t Smiling

Frank Sinatra Ignored John Gotti at a Hollywood Diner—By Nightfall, Sinatra Wasn’t Smiling Beverly Hills, California. February 14th, 1986. The…

Clint Eastwood’s Racist Insult to Muhammad Ali — What Happened Next Silenced Everyone

Clint Eastwood’s Racist Insult to Muhammad Ali — What Happened Next Silenced Everyone Los Angeles, California. The Beverly Hilton Hotel…

Brad Stevens Insulted John Wayne’s Acting—What Happened Next Changed His Life Forever

Brad Stevens Insulted John Wayne’s Acting—What Happened Next Changed His Life Forever Universal Studios Hollywood, August 15th, 1964. A tense…

Who Was Ernest J. King — And Why Did So Many Officers Fear Him?

Who Was Ernest J. King — And Why Did So Many Officers Fear Him? When President Franklin Roosevelt needed someone…

End of content

No more pages to load