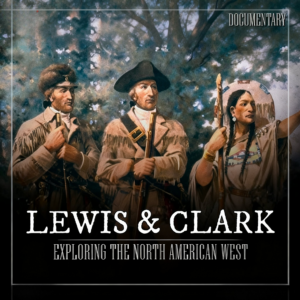

Lewis & Clark: The True Story of America’s Greatest Expedition

Before Manifest Destiny, before wagon trains and gold rushes and iron rails carved paths across the West, there was a river, and two men, carrying the hopes of a young republic on their shoulders, set out to follow it into the heart of a continent no white American had fully mapped. American had fully mapped.

Their names were Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, soldiers, scientists, diplomats, and explorers. But they were also something more rare, observers with open eyes, willing to learn from the people and the land as they went. Tasked by President Thomas Jefferson to chart the vast unknown after the Louisiana Purchase, their mission was part science experiment, part empire building, and part survival tale.

What unfolded was one of the most daring expeditions in American history, an 8,000-mile odyssey through uncharted terrain, where every bend in the river might bring revelations, danger, or a thrilling concoction of both. This is not the story of just a journey. It is the story of how a nation began to understand the true scale of the world it had just inherited, and the adventures that awaited them along the trail.

For Footprints of the Frontier, this is the tale of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, and their epic feats of discovery. In early 1803, President Thomas Jefferson quietly approached Congress with a proposal to change the course of American history. He requested $2,500, not a grand sum even at the time, to fund an exploratory mission to the Pacific Ocean.

On the surface, the stated goal was simple, open up new trade opportunities. But Jefferson’s true intentions stretched far beyond commerce. His vision was expansive and bold. He wanted the United States to one day span from coast to coast. This low-key request was the seed of what would become the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Jefferson handpicked Meriwether Lewis and tasked him with leading the mission, later joined by William Clark. Their job was multifaceted. They weren’t just supposed to blaze a trail westward. They were instructed to document the land’s geography, climate, wildlife, and plant life. They were to engage with native tribes, gather information on natural resources, and look for routes that might one day support trade and settlement.

Jefferson also hoped the expedition might pave the way for a lasting American presence in a region not yet under U.S. control. Jefferson’s confidential message to Congress on January 18, 1803, laid out not only the justification for the journey, but his broader thinking about America’s future relationship with native nations.

He observed that many tribes were growing increasingly resistant to selling their lands, even though the U.S. had been acquiring territory through what was technically voluntary agreements. As the population of settlers expanded, Jefferson argued that peaceful expansion would depend on two things, encouraging Native people to shift from hunting to farming and increasing access to American trade goods through a network of trading posts.

His strategy was clear. If Native communities adopted agriculture and settled lifestyles, they would need less land. And if trading posts supplied them with useful goods, tools, household items, comforts, they might be more inclined to trade away land that was otherwise unused for hunting. This shift, Jefferson believed, would nudge them closer to American-style society and make them more open to assimilation.

In his view, this wasn’t just a benefit for the U.S. It was a path to what he called their, quote, greatest good. Jefferson also saw an opportunity in the Missouri River, a route less traveled but ripe with commercial potential. He described the lands along the Missouri as home to many indigenous nations with established fur trading networks, mostly tied to European interests.

Jefferson believed that American traders could compete if they had better access. He envisioned a future where goods traveled by water from the Pacific coast to the Atlantic, using a combination of rivers and overland routes. This mission, Jefferson suggested, could be carried out by a small team of soldiers, who would chart the route, meet with tribes, and open up dialogue about trade.

meet with tribes, and open up dialogue about trade. He was careful with his wording. Jefferson knew this plan, though exploratory in nature, might stir up trouble if viewed as an aggressive land grab. By framing it as a scientific and commercial endeavor, he hoped to avoid suspicion from foreign governments, especially France and Spain, who at this time still had territorial claims in the West.

In short, the $2,500 Jefferson asked for was a cover. Behind it was a far-reaching plan to stretch the reach of the young American republic, to map a continent, and to subtly assert U.S. influence deep into lands not yet its own. With this move, Jefferson was laying the groundwork for an empire.

In the decades before the Lewis and Clark expedition ever even took shape, Thomas Jefferson had already been dreaming about what lay beyond the Mississippi River. As early as the 1780s, while serving as minister to France, Jefferson met with the explorer John Leonard to discuss plans for reaching the Pacific Northwest. That conversation planted a seed in Jefferson’s mind, a seed that would later grow into the core of discovery.

Long before he sent anyone west, though, Jefferson had been quietly collecting stories from explorers, reading their journals and piecing together what little was known about the uncharted frontier. Jefferson was especially inspired by the writings of Captain James Cook and Lepage Duprat.

Captain Cook’s detailed accounts of his third voyage to the Northwest Passage and Duprat’s descriptions of Louisiana left Jefferson eager to chart a land route across the continent. But Jefferson wasn’t alone in this race. British explorer Alexander McKenzie had already made history in 1793 by becoming the first non-Indigenous person to cross mainland North America north of Mexico.

His book, Voyages from Montreal, warned Jefferson that Britain had its sights set on the Pacific Northwest and its fur trade, especially along the Columbia River. That realization lit a fire under Jefferson to act quickly.

So in 1803, when Congress ultimately approved that aforementioned funding for an expedition westward, Jefferson wasted no time. He selected Meriwether Lewis, his personal secretary and trusted confidant, to lead the journey. Lewis, sharing Jefferson’s urgency, gathered supplies on the double, all with the help of Israel Whelan, a government supplier. Their shopping list for this quest was no small thing.

small thing. They packed hundreds of pounds of portable soup, dozens of gallons of high-proof alcohol, gifts for native tribes, mosquito netting, surgical kits, and even waterproof bags. Tobacco and medicine made the list too, essentials for both bartering and survival. But the trip was never just about survival or trade.

Jefferson never hesitated to reiterate that he saw the mission as a way to expand scientific understanding. He even told a French scientist that the expedition might find long extinct creatures, like mammoths or saber-toothed tigers or giant sloths still roaming the North American wilderness. You see, it was during that same time period many scientists weren’t convinced that extinction was real.

If they could dig up fossils, Jefferson reasoned, maybe they could also find living specimens. He truly believed animals like the megalonyx, a now extinct ground sloth with enormous claws, might still exist in remote corners of the continent. These ideas may sound far-fetched today, but at the time, they were grounded in the best scientific thought available. Jefferson didn’t stop at outfitting Lewis with gear and maps.

He also placed him on the newly created American Board of Agriculture. This move connected Lewis with the nation’s top minds in farming, manufacturing, and practical science. Jefferson believed these connections would enrich the expedition and help Lewis develop the kind of broad, useful knowledge the journey demanded.

Only two days after the funding was approved, Jefferson shared word of the planned voyage of discovery. His letter revealed the wide scope of his vision, not just a trek to the Pacific, but a full investigation of the land’s climate, geography, people, and natural resources. The journey would, Jefferson hoped, confirm America’s destiny to stretch from the Atlantic to the Pacific, while also offering glimpses into Earth’s ancient past.

This highlighted the fact that Jefferson’s choice to lead the journey wasn’t a traditional scientist or explorer. Rather, Captain Meriwether Lewis was a man who embodied the perfect blend of frontier grit and scientific curiosity.

Though Lewis lacked formal training in botany, zoology, or astronomy, Jefferson noted that his keen eye for detail and first-hand knowledge of wilderness would more than make up for it. As Jefferson explained in a letter written to Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton, Lewis had a remarkable store of accurate observation, and with the right guidance, he would know what to look for, and more importantly, how to record it.

To make sure Lewis was ready, Jefferson asked Barton, the respected naturalist, to mentor him in the weeks ahead. Barton was encouraged to provide Lewis with a checklist of the plants, animals, and native tribal customs most worth documenting. The president didn’t apologize for the request.

Instead, he leaned on their shared commitment to scientific discovery, believing that the pursuit of knowledge alone justified the effort. Even as Lewis was preparing for the journey, Jefferson was juggling otherpieces of his vision. He sent word to Illinois territory officials, urging them to negotiate with local tribes for land that would support U.S. expansion.

At the same time, Jefferson was working behind the scenes to orchestrate the legendary Louisiana Purchase, which would soon double the size of the nation and give Lewis and his party a much larger map to explore. As spring of 1803 approached, Lewis got moving.

On March 8th, Jefferson returned to his Virginia home of Monticello, while Lewis made his way to Harper’s Ferry. There, he supervised the crafting of specialized gear, everything from gunpowder and bullets to an experimental iron-framed boat that he hoped would withstand the rigors of river travel. Around this time, Lewis likely commissioned a custom branding iron used to mark boxes and barrels of supplies.

It may have also left its imprint on trees or camp supplies along their long path west. Very few artifacts from that part of the expedition remain today, but the branding iron was one of many tools designed to bring order and accountability to the unknown. With funding secured from Congress, supplies being purchased by aides, and instructions in hand from President Thomas Jefferson, Lewis’s next task was training, and for that, he turned to some of the brightest minds of the era.

Leaving Harper’s Ferry in late April, Lewis headed north to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he would study celestial navigation under the respected surveyor Andrew Ellicott. There, Ellicott gave Lewis not only hands-on instruction, but also a letter of introduction to Robert Patterson in Philadelphia, another scientific mentor.

Ellicott shared advice on using an artificial horizon, specifically a model that used a pan of water to reflect celestial bodies. Though it was simple and reliable, Lewis later noted it was only practical when observing bright objects like the sun. Dimmer light from stars or the moon made accurate readings far more difficult. By mid-May, Lewis had arrived in Philadelphia, a city brimming with intellectual life.

He sought additional guidance from experts like Patterson and Isaac Briggs, gathering advice on what tools and instruments were essential for the journey. Both men cautioned against using a theodolite, a delicate and difficult-to-transport surveying tool, and instead recommended a set of simpler, more durable gear. These essentials included two sextants, one specifically designed for back readings, a chronometer, an artificial horizon, a compass, a surveyor’s chain, and a full set of plotting instruments. Given the importance of timekeeping for determining location, the expedition’s chronometer had to be in perfect working order, a task Ellicott personally offered to handle.

President Jefferson, meanwhile, remained engaged in the details from Washington. he clarified some confusion about the instrument list, assuring Lewis that he was responsible for gathering what was needed and should trust the judgment of both Patterson and Ellicott. During his three-week stay in Philadelphia, Lewis continued to refine his plans and stockpile equipment.

He bought a wide range of supplies, from additional scientific gear to trade goods for native tribes, and even picked up a pair of flintlock pocket pistols from merchant Robert Barnhill. These pocket pistols, featuring hidden triggers, were designed for quick access and less chance of snagging when drawn. They were compact, powerful, and discreet, ideal for a journey filled with unknown dangers.

At the same time, Lewis continued gathering knowledge from leading thinkers in medicine, botany, and anthropology. He dined with old friends like Malin Dickerson, worked closely with Patterson, and accepted additional guidance from Dr. Barton. Patterson and accepted additional guidance from Dr. Barton. Notably, one Dr.

Benjamin Rush had provided him with questions aimed at better understanding Native American life, including their customs, spiritual beliefs, and health practices. This would prove integral down the road. Dr. Rush also provided a set of practical health guidelines for the explorers themselves. These weren’t just casual suggestions, either. They were a carefully crafted list of medical advice, tailored to help Lewis and his men endure the hardships of a long and dangerous journey across rugged terrain and into unknown territory.

With disease and death lurking in the shadows, abiding by a strict medical protocol was of utmost importance. Dr. Rush’s handwritten instructions, preserved in his personal notebook, laid out 11 key rules that Lewis was advised to follow. The heart of Rush’s message was prevention.

He urged Lewis not to power through any early signs of illness, but instead to stop, rest, and treat the symptoms with gentle remedies. Chief among them were his own purging pills, commonly used at the time to cleanse the system.Fasting, staying hydrated, and inducing a mild sweat with warm drinks were also recommended to stave off fevers. Several points focused on recognizing early warning signs of illness.

If Lewis or one of his men began to feel constipated or noticed a sudden loss of appetite, Rush considered those red flags. His advice was simple. Don’t ignore these changes, and treat them quickly with those same purging pills. When it came to managing exertion and diet during long marches, Rush stressed the importance of moderation.

Eating lightly, he believed, helped the body endure hard labor more effectively and reduced the risk of falling ill from overexertion. He also insisted that Lewis and his men wear flannel against the skin, especially in damp weather, to guard against cold and illness. This advice was taken to heart. Lewis purchased countless flannel shirts before setting out, and later made sure the entire crew was outfitted with flannel shirts during the journey. Rush was especially cautious about alcohol.

Rather than forbidding it outright, he recommended using spirits sparingly and only in specific situations, like after being drenched, worn out, or exposed to the cold and biting night air. In such cases, a small undiluted amount, no more than three tablespoons, could offer medicinal benefit, far more so than drinking larger amounts watered down.

To stay hydrated and healthy, Rush also suggested mixing sugar or molasses with water and a few drops of vitriol, a form of acid common in early medicine, creating a drink that was both refreshing and beneficial to digestion. He also advised washing chilled feet with spirits and starting each day by rinsing them in cold water. Both measures intended to toughen the feet and prevent illness from cold exposure.

Perhaps one of his most useful tips for the long road ahead was on recovery. Rush earnestly believed that after an exhausting march, lying completely flat for two hours would provide far more rest than sitting or lounging in any other position. It was a way to fully relax the body and prepare it for the next leg of the journey. Lastly, he gave specific advice about footwear.

Shoes without raised heels, he said, would offer better balance and support for the muscles in the legs, helping the explorers travel longer distances with less strain. All of these guidelines were not theoretical. They were based on Rush’s experience, common medical beliefs of the time, and a practical understanding of the grueling conditions Lewis would face.

Though modern medicine has moved beyond many of these practices, such as purging or the use of vitriol, the core of Rush’s advice remains familiar. Listen to your body, treat symptoms early, rest when needed, dress for the weather, and stay moderate in all things. Lewis also sent Jefferson a selection of rough maps, copied from George Vancouver’s coastal surveys, tools that would help fill in the geographic blanks of North America.

These charts, though hastily sketched, would serve as useful references for the journey ahead. Despite Lewis’s enthusiasm, recruiting suitable men for the expedition proved difficult. He wrote to Jefferson expressing frustration that only a few volunteers at the high physical and mental standards required for such an arduous journey. Nevertheless, he was optimistic, and by late May, he reported that nearly all supplies had been secured and hoped to return to Washington in early June.

Realizing he couldn’t keep waiting for the volunteers to come to him, Lewis remembered one man who above all could not only match his standards but supersede them. Thus, he took pen to paper in Washington City to write one of the most important letters not only of his life, but in American history. Addressed to William Clark, an old friend and fellow soldier, Lewis extended an invitation not only to join him on the government-backed expedition into the western frontier, but to help him lead it. In this letter, Lewis laid out his immediate travel plans.

He would soon depart for Pittsburgh, the city where their long voyage was set to begin. From there, he would descend the Ohio River in a 10-ton vessel, pushing southwest until reaching the Mississippi River, and then venture up the Missouri River as far as its waters would allow. It was an ambitious route, with miles of riverways and unknown wilderness ahead.

Lewis also described his personnel needs, outlining the types of men they would need to recruit for the mission. Ideal candidates were unmarried, physically strong, and seasoned in wilderness survival, preferably with experience as hunters.

He planned to stop at outposts like Fort Massac and Kaskaskia, hoping to find soldiers tough enough to face months of rugged travel, uncertain conditions, and high risk. But he also asked Clark to keep an eye out as well. If any suitable young men in Clark’s neighborhood met the criteria, Lewis wanted their names.

As a recruitment incentive, Lewis noted that all recruits would be promised a set of generous benefits. This included six months of advance pay, the option to leave the service after the journey’s completion, and a land grant equal to what had been given to veterans of the Revolutionary War. These perks were meant to attract quality men and reward their service in what was expected to be one of the most challenging undertakings in American history.

However, buried within Lewis’s letter was a far more secretive mission, one that he asked Clark to keep strictly confidential. The United States government, Lewis revealed, believed it was on the verge of acquiring the vast territory drained by the Mississippi River and its tributaries, including the Missouri. Though not yet finalized, the potential land deal, the future Louisiana purchase, would give the United States control over a massive swath of the continent.

In light of this, the exploration of the region had taken on a new urgency. Finally, Lewis extended a personal plea. He asked Clark to consider not just the rewards or the adventure, but the opportunity to face the hardships and honors of the journey together. If, therefore, there is anything under those circumstances in this enterprise which would induce you to participate with me in its fatigues, its dangers, and its honors, believe me, there is no man on earth with whom I should feel equal pleasure in sharing them as with yourself. Clark received the letter nearly a

month later, on July 17, 1803, and didn’t hesitate long. The very next day, he wrote back and accepted. It was the beginning of a partnership that would go down in American history. Two men leading a hand-picked crew into the uncharted West, driven by science, exploration, and a vision of what their young country would one day become.

William Clark had no other choice but to accept. On June 20, 1803, President Thomas Jefferson finalized a document that would shape one of the most important expeditions in American history. Addressed to Meriwether Lewis, this detailed set of instructions laid out the exact expectations, goals, and safety considerations. Lewis was expected to chart his course with care.

He was told to record latitude and longitude at every notable point along the river, especially where other rivers met, or at islands, rapids, and natural landmarks that would last for generations. Jefferson wanted a map that could be trusted and used again, so Lewis was instructed to use everything from his compasses and log lines to celestial observations to get it exactly right. But remember, the journey wasn’t just about land and water.

It was about the people too. Jefferson urged Lewis to learn as much as he could about the Native American tribes who he would encounter. What were their names? How many people lived in each group? What did they wear, eat, and believe? What languages did they speak? And what diseases affected them? Jefferson also wanted insight into their laws, customs, and potential for trade.

Understanding the tribes would not only help future diplomacy, it would also serve Jefferson’s broader vision of expanding American influence through peaceful engagement. In that spirit, Jefferson advised Lewis to treat all Native peoples with respect and friendliness. He was to reassure them that the expedition posed no threat and explained that the United States wanted to trade and maintain peaceful relations.

If any tribal leaders wanted to visit Washington, Lewis was encouraged to arrange for them to do so, with the government covering the cost. Lewis was also asked to observe plants, animals, and geological features, especially anything new to American science. He was to note the soil, the weather, and even the dates when certain flowers bloomed or birds appeared. Jefferson wanted the full picture of what made the land unique, from rare minerals to extinct species.

A lesser discussed point of the journey was that Lewis also carried with him samples of the smallpox vaccine, known then as the kindpox. Jefferson hoped that Lewis could teach the native tribes how to use it and explain its power to protect against deadly disease. This too was part of the broader goal, sharing knowledge in the hopes of building trust.

When it came to safety, Jefferson left the final judgment to Meriwether Lewis himself. If the expedition ran into serious resistance, whether from a foreign military or an overwhelming threat, he was instructed to turn back rather than risk lives. Remember, the priority was survival, not heroics, and Jefferson made that clear.

Bringing back the information was more valuable than pressing forward recklessly. And finally, Jefferson included a practical fallback plan. If returning the way they came proved too dangerous, Lewis had the authority to find passage by sea, around Cape Horn or the Cape of Good Hope.

He would haveaccess to open letters of credit to buy supplies, food, or transportation, trusting in the financial backing of the United States government to cover any needs. All of this was put down in writing and signed by Jefferson himself. With this letter, the stage was set for the Corps of Discovery to begin its historic journey. The plan was ambitious, the expectations ran high, and the risks reeled. But Lewis now had his roadmap, not just for the rivers ahead, but for how to navigate every single challenge that might come with them.

By the summer of 1803, months of planning, training, and political maneuvering had finally given way to action. The final preparations for Meriwether Lewis’s expedition were now moving at full speed. Time seemed to blur as July rolled in, bringing with it news that would forever change the shape of the nation.

On July 4th, 1803, word of the Louisiana Purchase Treaty was made public in Washington, D.C. Overnight, the scale and stakes of Lewis’s mission grew exponentially. Just 11 days later, Lewis reached Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. There, he personally oversaw the building of a large keelboat, roughly 55 feet long with a 32-foot mast and benches to seat 22 oarsmen.

He also picked up a long, narrow piro, another river vessel measuring over 40 feet. These specific boats would serve as the main lifelines of the journey, carrying supplies, weapons, scientific gear, and the crew that would help shape American history. But, of course, nothing ever goes exactly according to plan.

Delays pushed the departure back more than a month as the boat builders worked to complete the keelboat. Finally, on August 31st, with construction finished and the vessel fully loaded, Lewis and his small team, 11 men in total, pushed off into the slow current of the Ohio River. This long-awaited expedition had officially begun. As the boat slipped away from the banks of Pittsburgh, Lewis probably couldn’t help but recall a letter he had sent to his mother not long before.

In it, he had tried to ease her worries, writing with confidence about his plans. Quote, I shall set out for the western country. My absence will probably be equal to 15 or 18 months. I go with the most perfect pre-conviction in my own mind for turning safe and hope therefore that you will not suffer yourself to indulge any anxiety for my safety. Adieu, and believe me, your affectionate son, Meriwether Lewis.

” With those words echoing in his thoughts and the waters stretching out before him, Meriwether Lewis sailed into the unknown, armed with optimism, prepared by training, and driven by a mission that would redefine a nation. The best was yet to come. By September 1st, 1803, Meriwether Lewis began writing what would eventually become one of the most significant first-hand records of American exploration, the Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

As he recorded the initial miles of their journey down the Ohio River, he set the tone for a voyage that would chronicle not just geography and weather, but daily life on the frontier, challenges faced, and discoveries made.

On October 15th, after weeks of solo preparation and river travel, Lewis finally reunited with William Clark of Clarksville, Indiana Territory. Clark wasn’t alone. He brought along York, his enslaved assistant that would play a key role in their journey ahead. Over the following two weeks, the two leaders carefully selected nine skilled civilians from a pool of eager volunteers.

Strength, wilderness experience, and the ability to handle hardship were critical qualities for any man hoping to join this dangerous venture. Meanwhile, the political landscape back in Washington also shifted dramatically. On October 20th, the U.S. Senate officially ratified the Louisiana Purchase Treaty, solidifying the nation’s acquisition of a vast expanse of land west of the Mississippi River.

That landmark moment gave new urgency and importance to Lewis and Clark’s mission. They were now exploring recently acquired American territory. By mid-November, the Corps of Discovery reached the point where the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers met. Corps of Discovery reached the point where the Ohio and Mississippi rivers met.

While encamped there, Lewis and Clark used the opportunity to sharpen their navigational skills, practicing how to calculate their position using surveying tools to determine latitude and longitude, essential for accurate mapping of the terrain ahead. On November 28th, the expedition pulled into the frontier town of Kaskaskia, Illinois, home to the U.S. Army Post. There, they recruited more soldiers to round up their team.

This included John Ordway, a soldier whose immensely detailed diary would provide the missing information from the journaling of Lewis and Clark themselves. A little over a week later, on December 6th, Lewis rode on horseback to St.

Louis, locatedjust across the Mississippi River, to gather additional equipment and provisions in preparation for winter. The star charts were specifically in need of updating. Back on the Illinois side, Clark arrived at their planned winter headquarters on December 12th. The very next day, construction began on Camp Dubois, a fortified outpost that would serve as their base until spring. It was strategically positioned just north of St.

Louis, placing them near both the American and French-controlled regions during the final days of a major political transition. That transition came to a head on December 20th, when France officially transferred ownership of the Louisiana Territory to the United States. Ten days later, America took full possession. And with that, the stage was fully set.

Lewis and Clark weren’t just heading into uncharted wilderness. They were leading the first major American expedition to brand new territory, a journey that would soon define the Corps of Discovery, neared completion. The cold Midwestern winter still held the land in its grip, but inside the camp, the focus was on discipline, morale, and keeping everyone occupied. Lewis and Clark walked a fine line as leaders.

The men needed to remain upbeat and cooperative, but too much idleness risked stirring resentment. So, the captains filled these early days with purpose. Men were assigned tasks as hunters, cooks, fishermen, and caretakers of the camp. Others worked alongside the captains to prepare the scientific gear for the journey ahead.

Regular shooting contests and near-daily hunting excursions kept the men sharp in the camp well-stocked with venison and waterfowl. sharp than the camp well stocked with venison and waterfowl. As February arrived, the snow began to melt, but a new challenge surfaced. William Clark fell ill.

His condition was unclear, and he grew worse even as spring hinted its return. Lewis stepped in with a dose of homemade walnut bark pills, and slowly but steadily, Clark began to recover. By the time the frozen Missouri River began to shift and break apart, the captains knew it was time to move quickly.

Their next phase would involve deep engagement with indigenous nations, tribes that dotted the landscape they were about to explore, and careful planning would be essential. On March 9th, Lewis traveled to St. Louis to witness a historic event, the formal handoff of the Louisiana Territory from France to the United States. Just weeks later, on March 26th, he received news that left him both frustrated and disappointed.

Clark’s commission had finally come through, but only as a lieutenant, not a captain. While Jefferson had promised equal authority, the paperwork failed to reflect it. Still, Lewis kept this difference in rank hidden from the men. On the trail, both captains would lead together. the men. On the trail, both captains would lead together. At the end of March, tensions flared within the Corps.

Privates John Shields and John Coulter, two capable men who would later prove essential to the expedition, got into a heated fight with Sergeant Ordway and even threatened his life. The incident nearly led to charges of mutiny, but after expressing deep remorse, both men were forgiven. Just days later, on March 31st, Lewis and Clark held a formal ceremony inducting 25 handpicked men into the Corps of Discovery.

Five others were designated to return with the keelboat the next spring, after the expedition had crossed into unknown terrain beyond the Rocky Mountains. April brought forth both celebration and urgency. Lewis and Clark took a canoe to St. Louis, where they attended a dinner and a ball in their honor. It was a brief moment of civility before they headed back into the wild.

Then, on May 14, 1804, the Corps of Discovery finally set off again. Under Clark’s command, over 40 men pushed off from Camp DuBois and began rowing up the Missouri River. In mid-May, the Corps of Discovery reached the river town of St. Charles, Missouri, where they paused to wait for Captain Meriwether Lewis to rejoin them from St. Louis.

While they waited, discipline issues emerged. On May 17th, Private Collins, Hall, and Warner were court-martialed for going absent without leave. Collins faced additional charges and was sentenced to 50 lashes. Hall and Werner were also found guilty, but had their punishment suspended. Lewis finally departed St.

Louis on May 20th, traveling with Army Officer Amos Stoddard, key traders, and other prominent citizens. A fierce thunderstorm forced the group to take shelter in a small cabin before pressing onward. The next afternoon, May 21st, the Corps of Discovery officially launched its westward journey from St. Charles.

With a ceremonial blast from the swivel gun and three hearty cheers, the expedition pushed off through heavy winds, limiting their progress to just over threemiles. That night, storms continued to batter their camp along the North Shore. You see, the Corps was traveling in one 55-foot keelboat and two pirogues, carrying supplies and scientific instruments essential for their mission.

Despite occasionally helpful winds, the Missouri River’s current was strong and unrelenting. The men made headway mostly by rowing or hauling the boats with ropes along the bank. A few days later, on May 25th, they passed Le Charette, the final outpost of Euro-American settlement on the river.

By June 26th, the Corps reached Kaw Point, where the Kansas River meets the Missouri in what is now Kansas City. Fearing potential conflict with the nearby Kansa people, they fortified their position but faced no attacks. The crew took this opportunity to rest, patch up the boats, and prepare for the long miles ahead. However, not all went smoothly.

Just a few days later on June 29th, Private Collins was caught stealing whiskey while on duty and was sentenced to receive a brutal 100 lashes. Private Hall, who decided to drink with him, was also punished with 50 lashes of his own. Nevertheless, July 4th was honored with a special naming.

Lewis and Clark christened a creek near modern-day Atchison, Kansas as, quote, Independence Creek. Just a week later, on July 11th, they crossed into present-day Nebraska. That same night, Private Willard was discovered asleep during his watch, a serious offense that could have jeopardized the entire camp. He was also sentenced to 100 lashes and ministered in four rounds of 25.

By July 21st, the expedition reached the mouth of Nebraska’s Platte River, some 640 miles from their starting point in St. Louis. On July 30th, the Corps made camp on a bluff they called Council Bluff, near what is now Fort Calhoun. There, on August 3rd, they held their first formal meeting with native leaders, sitting down with chiefs from the Otto and Missouri tribes.

Though the tribes hoped for firearms, Lewis and Clark came bearing medals and flags and words of peace. The initial diplomatic effort, while imperfect, marked the beginning of many such encounters. Not long after this, on August 4th, one private Moses Reed deserted the expedition. The captains issued orders to bring him back, dead or alive.

He was caught by August 18th and severely punished. Reed was forced to endure running the gauntlet, a brutal flogging ritual, and was formally expelled from the Corps. However, with survival outside the group unlikely, he was allowed to stay with them through the winter.

The Corps also suffered its first and only fatality on August 20th, when Sergeant Charles Floyd died from what was likely a burst appendix. He was buried with full honors on a hill along the Missouri that now bears his name. Soon after, the men held an informal vote to fill Floyd’s position. Private Patrick Gass was chosen as the new sergeant. That same week, the Corps’ youngest member, George Shannon, went missing while searching for stolen horses.

Luckily, he was found alive not long after. On August 27th, the expedition set up camp near the mouth of the James River, within Yankton Sioux Territory. A few days later, on August 30th, Lewis and Clark met with Yankton leaders. As with earlier tribes, the Sioux hoped to receive rifles and alcohol, items the captains did not provide.

Instead, they invited the Yankton chiefs to visit President Jefferson in Washington, hoping to establish trust and set the tone for future negotiations. In early September of 1804, the Corps of Discovery faced a moment of relief when Private George Shannon, who had been missing for over two weeks now, was finally found along the banks of the Missouri River.

Starving and out of ammunition, Shannon had survived an exhausting 16-day ordeal. His safe return was a much-needed morale boost, as the expedition continued deeper into unfamiliar territory and the disappearances ratcheting up. By September 20th, the Corps had pushed nearly 1,300 miles upstream from their original departure point, reaching the area known as Big Bend in what’s now central South Dakota.

Just days later, on September 25th, the group encountered its first serious diplomatic crisis. A tense standoff with a band of Lakota Sioux near present-day Pierre nearly erupted into violence. But thanks to the measured words of Black Buffalo, the elder chief among the Lakota, tensions cooled and bloodshed was narrowly avoided. In October, internal challenges surfaced yet again.

On the 13th, Private Newman was found guilty of speaking out against the leadership. This was a serious offense that resulted in his expulsion from the Corps. Like Private Reed before him, Newman was allowed to stay with the group until spring for safety’s sake, but his standing within the team was formally strict. The expedition eventually arrived in the lands of the Mandanpeople in modern-day North Dakota.

Over the next several days, Lewis and Clark met with the tribal leaders of both the Mandan and Hidatsa nations. Realizing the need to settle in before the brutal northern winter, the captains selected a site across the river from the main Mandan village and began construction of their winter base. They named it Fort Mandan in honor of their hosts.

A few days later, on November 4th, the Corps made a key decision that shaped the remainder of their journey. They hired Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian fur trader living among the Mandan, as an interpreter. More significantly, one of his wives, a young and pregnant La Mise-A-Chan woman named none other than Sacajawea, was also brought on.

Her language, skills, cultural knowledge, and later contributions would prove invaluable. From that point through December, life at Fort Mandan was a mix of hard work and survival. The men spent their days building the fort, hunting buffalo for food and hides, battling winter illnesses, and maintaining trade relations with local and visiting native tribes.

Occasional tensions flared among the crew, but discipline was maintained and scientific documentation quietly continued in the background, Lewis observing, recording, and collecting as often as time allowed. On December 24th, after weeks of labor and bitter cold, Fort Mandan was officially completed. The following day, Christmas brought a much-needed break. The Corps celebrated with what little luxuries they had, some special food, a ration of rum, and a night of music and dancing inside the newly finished fort.

It was a moment of warmth and camaraderie in was marked by a mix of routine survival, unexpected drama, and a renewed sense of purpose as the Corps of Discovery waited for winter to pass. The new year opened with a team focused on hunting game and drawing detailed maps of the terrain they had already covered.

But as temperatures plunged to life-threatening lows, dropping to 40 degrees below zero at times, routine tasks could turn deadly. On January 9th, a group of villagers from Knife River staggered into the fort, quote, nearly frozen. That same night, one of the course hunters and a young native boy failed to return, prompting a desperate but unsuccessful search. With the odds of surviving a night in that cold seeming slim, hope dwindled.

Against all expectations, the boy was eventually found alive by a Mandan search party, and the missing hunter managed to find his way back on his own, somehow. Episodes like these added real danger and tension to the otherwise quiet and bitterly cold days of winter. Not all the surprises of the season came from the wilderness.

On January 14th, Clarke recorded an incident that would rarely make the history books, but it speaks volumes about human behavior on the frontier. Several of the men had contracted venereal disease, likely from relationships with man and woman. These interactions, romantic, transactional, or otherwise, added an often overlooked layer of emotional complexity and cultural friction to the expedition’s story. Discipline within the ranks also kept flaring up in surprising ways.

On February 9th, Private Howard returned after dark and, instead of asking the guard to open the gate, climbed over the fort’s wall. A curious native onlooker followed his lead and scaled the wall too. Howard’s breach of security was taken seriously. He was sentenced to 50 lashes, though Lewis ultimately chose to suspend the punishment.

This was the last formal disciplinary trial of the journey. Because two days later, on February 11th, the expedition experienced a very different kind of milestone. Sacagawea gave birth to her first child, a baby boy named John Baptiste Charbonneau. William Clark affectionately nicknamed the child Pompey, and he quickly became a cherished member of the traveling party. By early April, winter was finally on the retreat.

On April 7th, the Corps packed up camp and pushed forward. The keelboat, filled with specimens, maps, and reports for President Jefferson, were sent downriver with a dozen men. The remaining permanent party, the true Corps of the Corps, headed west using two P-Rogues and six hand-carved dugout canoes.

As the journey continued into late April, the landscape shifted dramatically. On April 25th, the group reached the confluence of the Yellowstone River, a major northern branch of the Missouri. Two days later, they crossed into present-day Montana, where they began to witness the scale of the uncharted west firsthand.

Herds of buffalo, numbering in the tens of thousands, blanketed the plains. Then on April 29th, the men came face to face with one of the most feared creatures of the frontier, the grizzly bear. That day, two large bears were spotted. Both were shot and wounded, and one actually charged Meriwether Lewis, chasing him for nearly 100yards. Fortunately, it had been badly injured and couldn’t keep up.

Lewis and his men managed to reload and bring it down. Though this particular bear was relatively young, weighing in at just about 300 pounds, the experience underscored the animal’s reputation and the Corps of Discovery maybe learned their lesson. Don’t mess with the bear. Lewis remarked with some awe that it was, quote, astonishing to see the wounds they will bear before they can be put to death while native hunters armed with bows and outdated firearms had every reason to fear the grizzly lewis believed skilled riflemen could handle the threat though he now knew firsthand

there was no small challenge in may the core Discovery’s encounters with the grizzly bear actually became a regular and nerve-wracking part of life along the Missouri River. These massive creatures, which Lewis had foolishly once thought might be exaggerated in reputation, quickly proved themselves to be among the most dangerous animals in all of North America.

On May 5th, near what’s now Wolf Point, Montana, Clark and expert hunter George Druyard brought down the largest grizzly yet seen by the expedition. Despite being hit by 10 bullets, including five through the lungs, the animal still managed to swim halfway across the river before finally collapsing 20 minutes later. It never charged, but its pained roars and sheer willpower left a lasting impression.

Lewis called it a most tremendous-looking animal, and that night, everyone slept a little more cautiously. The very next day on May 6th, Lewis had a shift in perspective. Near the Milk River, he wrote about the bears in terms of ownership and dominance, referring to them, half seriously, half sarcastically, as quote, gentlemen.

For Lewis, that word carried weight. In his mind, gentlemen were landowners, and in this case, grizzlies ruled the cottonwood bottoms and brushy riverbanks with the authority of kings. On May 11th, that royalty nearly took the life of one of their own. Private William Bratton, recovering from an infected hand, had been allowed to walk along the river to get some fresh air.

What he didn’t expect was a grizzly charging him. Though Bratton managed to shoot it once, the wounded animal chased him for hundreds of yards. Bratton made it back in one piece, but barely. Lewis led a search party and found the bear’s trail.

They tracked it through thick brush until they found the animal still alive and dug into a self-made den, despite that bullet going through its lungs. It took another two shots to the skull to finish it off. Constant experiences like this began to wear on the men. Quote, These bears being so hard to die rather intimidates us all, Lewis wrote in his journal.

I must confess that I do not like the gentleman and had rather fight two Indians than one bear. While Bravado laced these words, Lewis’s statement carried real fear. These grizzlies simply would not go down easy. And a few days later on May 14th, the grizzlies struck again. Six experienced hunters fired multiple rounds into a charging bear, only to have it chase each man individually as they scattered. One had to dive into the river to escape.

Another jumped off a 20-foot bank. It was only when someone got a clear shot to the bear’s head did the rampage finally end. When they opened up the carcass, they found eight bullets from different directions lodged into the bear’s body. That same day, nature added insult to injury. A sudden windstorm tipped one of their P-roads, dumping crucial gear, including their journals, into the river.

While panic set in, it was Sacagawea who calmly collected floating supplies and saved the day. Clark praised her quick thinking, noting it in his journal as one of her many, many contributions to the team. Later that month, on May 26th, Lewis saw the Rocky Mountains for the first time. At first, he was thrilled. This was the destination they’d worked so hard to reach.

But reality set in fast. Snow-capped peaks loomed ahead, signaling that even greater challenges lay before them. On June 1st, they hit an unexpected fork in the Missouri River. One branch flowed north, the other branch flowed south, and the men voted on which one to take. Only Lewis and Clark believed the southern route was correct, but the rest of the Corps was unsure.

Yet when another vote days later brought the same result, the team just agreed to trust their leader’s judgment, and it proved to be the right call. On June 13th, a scouting group led by Lewis reached the Great Falls of the Missouri, proof that they were still on the right path. From there, however, the going got tougher.

The falls couldn’t be navigated by water, so the team had to carry all their gear 18 miles across rugged terrain. The portage took nearly six weeks, testing the endurance and morale of every man involved. In early August, Sacagawea serendipitously recognized a rock formation from her childhood,Beaver Head Rock. It signaled that they were nearing Shoshone territory. On August 12th, Lewis and three men crossed the Continental Divide at Lemmy Pass, marking a major milestone.

At the same time, the shipment that they had sent earlier reached President Jefferson in Washington. The next day, on August 13th, Lewis encountered a new band of 60 Shoshone warriors. Tensions were high, but Lewis managed to establish peaceful intentions. But trust didn’t come easy. When suspicions flared on August 16th, Lewis handed his own rifle to the Shoshone chief to demonstrate his sincerity.

The other men followed his lead, surrendering their weapons temporarily, a very bold move that helped secure the alliance. This gamble paid off in a way that no one expected. The next day on August 17th, Sakajewi was reunited with her long-lost brother, Kamowe, who now just so happened to be a Shoshone chief.

Through her translation and personal connection, the Corps successfully negotiated for the horses they needed to cross the daunting Rocky Mountains ahead. In just a few months, the Corps had gone from dodging death by grizzly to building fragile but critical alliances with native nations. It was a constant balance of force and diplomacy, danger and survival.

But through it all, they kept pressing forward, wounded, wiser, and determined. By early September 1805, the Corps of Discovery found themselves approaching the eastern face of the Bitterroot Mountains, near what is now Sula, Montana. After weeks of travel through rugged terrain, they were greeted by the Sitterroot Salish people, also known as the Flathead Indians, who offered the weary travelers a much-needed break.

much-needed break. The Salish, living in a camp of 33 lodges with roughly 80 men and about 400 people in total, welcomed the expedition warmly. Over the next two days, Lewis and Clark’s team rested, traded for horses, and gathered strength for what lay ahead. That brief respite proved essential too, because soon they began what would become the most grueling stretch of their entire journey, crossing the Bitter Roots.

Setting out from Traveler’s Rest, near present-day Lolo, Montana, the Corps plunged into an unforgiving mountain range. For eleven brutal days, the men slogged through deep snow, barely able to see the trail. With supplies running low and wild game scarce, they were eventually forced to slaughter and eat some of their young horses just to survive.

When they finally emerged on September 22nd onto the Weeite Prairie in western Idaho, salvation came in the form of the Nez Perce. western Idaho, salvation came in the form of the Nez Perce. This native nation generously took in the exhausted explorers, offering them dried fish and boiled roots.

But days of starvation had weakened the core’s stomach. Nearly everyone fell sick from overeating. But by September 26th, the team had followed the Clearwater River westward and found a suitable spot near present-day Orofino to set up camp and begin building canoes. Recovery was slow and progress lagged while the men regained strength.

When the boats were finally ready, the expedition pushed forward again in early October. A few days later, the group crossed into present-day Washington, where the Clearwater met the Snake River near the towns now known as Lewiston and Clarkston. They followed the Snake down to the mighty Columbia River, reaching it near what’s now the Tri-Cities area. From there, the Columbia bent westward, marking the modern border between Oregon and Washington.

Then, on October 18th, through thick fog, Clark caught a distant glimpse of Mount Hood, proof they were nearing the ocean. By October 22nd, they had arrived at Celilo Falls, a dangerous 55-mile stretch of rapids and canyons that would test both their navigation skills and their nerves. Still, they pushed forward with determination.

In early November, Clark penned an optimistic line in his journal. Great joy in camp we are in view of the ocean. But that joy was premature. What they had seen was the wide estuary of the Columbia River, not the open sea, and they still had 20 miles to go.

Just one day later, heavy waves forced them to make camp before they could push further. Another attempt on November 10th was cut short again by fierce conditions. Then, on November 12th, a violent storm rolled in. Hail, rain, and powerful winds hammered their exposed camp, sending logs crashing along the shoreline.

To protect their canoes from the tumbling timber, the men buried all but one under heavy stones, and eventually, they retreated inland to wait out the storm. Finally, on November 15th, the weather cleared enough for safe passage. That day, they reached the Pacific and landed on a sandy beach that they would call Station Camp. They stayed there for 10 days, hunting, bartering with the Chinook and Klatsop tribes, and exploring the surrounding coastline.On November 24th, the Corps held a vote to decide where they should spend the winter.

Notably, both Sacagawea and York were given equal say in this matter, an uncommon gesture of inclusion in an era that often excluded both indigenous women and black Americans from decision-making. Following the advice of the local tribes, they selected a site across the river in present-day Oregon, where game was more abundant.

Construction of Fort Clatsop began on December 8th near today’s Astoria, and by the end of the month, the wooden fort was completed. near today’s Astoria, and by the end of the month, the wooden fort was completed. But any sense of comfort was actually quickly washed away by the relentless Pacific Northwest rain.

It poured nearly every day of their three-month stay, soaking their clothes, supplies, and morale alike. Despite the hardships, the Corps had reached their goal. They had made it to the edge of the continent. Now, all that remained was to turn around and make the long journey home. The new year of 1806 began with a burst of excitement on the Oregon coast. The new year of 1806 began with a burst of excitement on the Oregon coast.

Just days before January rolled in, local indigenous people brought news to Fort Klatsop that a whale had washed ashore somewhere to the south. This unexpected event added a new layer of interest to the Corps of Discovery’s otherwise routine winter, which they had been spending finishing the fort, celebrating the turn of the year, and continuing trade with nearby tribes.

By January 10th, Captain Clark and most of his team had returned to Fort Clatsop from their visit to the whale site. While Lewis’s journal gave a broad overview of the trip, it was in the accounts of Ordway and Whitehouse that some vivid extra details appeared. They mentioned that the group had brought back large jawbones, and of Ordway and Whitehouse that some vivid extra details appeared.

They mentioned that the group had brought back large jaw bones, and what Ordway described as black bones that he thought were rather handsome. These were almost certainly sections of baleen, long comb-like strips from the mouths of whales used to filter food from sea water.

Each whale could carry hundreds of these yard-long plates, and they would have been an unusual sight for the men of the expedition. The whale’s fat was even more valuable. Blubber was high in calories and offered a much-needed break from their typical lean winter diet of elk and roots. It’s very likely that the whale oil rendered from this blubber was put to practical use in the oil lamps the Corps had brought along, especially during those long, dark, rainy days on the Pacific coast.

Just like the rest of their journey, the Corps didn’t waste an opportunity to use every resource they could get their hands on, particularly when it came to food and fuel. By March 23, 1806, the long winter at Fort Clatsop came to an end. The Corps was ready to head home, eager to retrace their steps and report their findings.

Traveling back along the Columbia River, they reached the Great Falls by April 18. Here they hoped to purchase horses for the difficult trip back over the Rocky Mountains. The local Native Americans, however, knew just how desperate the men were and asked for higher prices. In the end, the Corps was only able to afford four horses.

On April 28th, the expedition eventually left the Oregon Territory behind and moved east, following the Columbia until it met the Snake River in present-day southeastern Washington. Just a few days later, on May 3rd, they were hit by a late-season snowstorm, but were fortunate to reconnect with the familiar Nez Perce chief and his entourage.

By May 5th, the expedition had made it to what is now Idaho and picked up the Clearwater River. However, it quickly became clear that they had begun the return journey too soon. The snowpack in the Bitterroot Mountains was still too deep to cross safely.

So, on May 14th, they set up camp in what is now the Nez Perce Reservation, and waited nearly a month for the snow to melt. Once conditions improved, the Corps packed up on June 10th. By June 14th, they had arrived at the edge of the Bitterroots, and with the help of three skilled Nez Perce guides, they managed to trim hundreds of miles off their route. On June 29th, the expedition crossed into western Montana through Lolo Pass.

On July 3rd, the Corps decided to split into two teams to explore more land on their way back. Lewis led one group down the Missouri River, while Clark took the other down the Yellowstone. Both parties would break off into smaller detachments to survey various areas. Later that month, on July 25th, Clark reached a striking rock formation along the Yellowstone River and named it Pompeii’s Pillar in honor of Sakajuiya’s young son. Clark carved his name and the date into the rock, a rare and lasting physical trace of theentire journey. Just a day later, on July 26th, Lewis’s group ran into serious trouble. While

traveling on horseback, they crossed paths with a small group of Blackfeet warriors. That evening passed without incident, but by morning, tensions escalated. Two Blackfeet attempted to steal guns and horses, and in the ensuing skirmish, both were killed. Fearing retaliation, Lewis and his men rode hard for nearly 24 hours to get clear.

Clark’s group, meanwhile, had a much smoother time. On August 2nd, they reconnected with the Missouri River and entered what is now North Dakota. But on August 11th, Lewis’s luck ran short. He was accidentally shot in the buttocks by one of his own men. Finally, on August 12th, the two parties were reunited near the mouth of the Knife River in western North Dakota.

parties were reunited near the mouth of the Knife River in western North Dakota. Two days later, they were welcomed back by the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes. On August 17th, the Corps said goodbye to Charbonneau, Sacagawea, and little Jean-Baptiste, who stayed behind with the Mandans. Clark even offered to raise the boy as his own, a sign of the deep bonds formed during the journey.

raise the boy as his own, a sign of the deep bonds formed during the journey. Now traveling with the river current, the Corps made impressive time, covering over 70 miles a day. Their road home ended on September 23, 1806, when the Corps of Discovery finally arrived back in St. Louis. Their 8,000-mile trek had taken two years, four months, and ten days.

They had mapped vast stretches of the continent, made first contact with dozens of native nations, and returned with detailed records of plant life, animal species, and geography never before documented by Americans. Meriwether Lewis returned to Washington, D.C. on December 28, and by the end of February, President Jefferson nominated him to serve as governor of the Upper Louisiana Territory, a new chapter not just for a man who had finished one of the most extraordinary adventures in American history, but a new chapter for the country at large.

The full scope of what Lewis and Clark achieved on their expedition is difficult to fully catalog. The records they kept, the plants and animals they documented, and the maps they created helped transform the known boundaries of the young United States. Yet beyond the big-picture milestones and scientific breakthroughs, the journey was also packed with quieter victories, moments of resilience, of cultural exchange, of discovery both grand and subtle. These side stories, many of them overshadowed by the sheer

magnitude of the expedition, are still very much worth appreciating for the ways they shaped the decades that followed. One of President Thomas Jefferson’s main objectives for the Corps of Discovery was the aforementioned gathering first-hand knowledge of the Native Nations living across the newly acquired Louisiana Territory and beyond. This wasn’t just a scientific mission, it was a political one.

Jefferson wanted Lewis and Clark to make it known that the U.S. government now claimed this vast interior land, and that all Native Nations within it should recognize the authority of the quote Great Father in Washington. That message was expected to be delivered with both diplomacy and a show of strength.

To help with this, the Corps carried leather-bound journals to document tribal interactions, and they brought bundles of those trade goods, beads, mirrors, sewing needles, medals, and ribbons to offer as gestures of goodwill. The expedition met dozens of Native groups along the way, most of whom were welcoming and generous with their knowledge.

They helped guide the Corps, traded food and supplies, and shared details about the landscape. Still, not every encounter was peaceful. A particularly tense episode unfolded on September 25, 1804, when the expedition reached the lands controlled by the Teton Sioux, near what is now central South Dakota.

The Lakota, led by Black Buffalo and the Partisan, stopped the corps and demanded gifts in exchange for passage. Captain Lewis, misreading the dynamics, insulted Partisan by giving gifts first to Black Buffalo. That mistake nearly caused a violent clash. At one point, the Lakota warriors grabbed one of the Corps’ boats and refused to let go. Swords were drawn, muskets were raised.

Only the quick thinking of Black Buffalo de-escalated the situation. The Corps eventually moved on after sweetening their offering with more trade goods and a bottle of whiskey. A similar standoff occurred again when the Corps tried to leave, but a few puffs of tobacco kept things from boiling over. Over time, the expedition developed a deeper understanding of many native cultures they encountered.

They learned about traditions, languages, family structures, spiritual beliefs, and social norms. Some customs were shocking tothe men, like arranged marriages involving young girls, or the practice in certain tribes of marrying multiple wives, sometimes their own sisters. They also witnessed fierce inter-tribal rivalries and saw evidence of long-standing wars.

The Sioux, for instance, bragged openly about having wiped out several nearby tribes such as the Cahokia and the Missouris. But the expedition wasn’t just about those politics and diplomacy. It was also about the aforementioned scientific enterprise. They carefully recorded the terrain, charted river systems, and drew over 140 maps, many of which were used for years after their return.

Their observations laid the groundwork for America’s eventual expansion all the way to the Pacific. The Corps documented more than 200 previously unknown plants and animals, at least unknown to the European Americans. Among the creatures they described for the first time were the grizzly bear, pronghorn, swift fox, and mule deer.

They also wrote about birds like the greater sage grouse and Lewis woodpecker, amphibians like the western toad, and reptiles including the horned lizard and western rattlesnake. In the rivers they traveled, they identified species such as the blue catfish and white sturgeon. Plant life was just as important to the expedition.

Lewis gathered hundreds of botanical samples, although many were lost to flooding or other mishaps. Still, about 237 of his specimens survive and are now preserved in collections at the Philadelphia Herbarium. These include now familiar species like purple coneflower, buffalo berry, wild rose, ponderosa pine, and blue flax.

The American Philosophical Society sponsored the scientific side of the expedition. Before departing, both captains received instruction in a wide range of fields, astronomy, mineralogy, ethnology, and more. By the time they returned, they had made contact with over 70 Native American tribes, taken notes on dozens of unknown regional dialects, and gathered enough data to keep scientists and scholars busy for generations. The journey’s influence continued long after the Corps returned home, too.

Patrick Gass, a soldier on the expedition, was the first to publish an account of the trip in 1807. In 1814, a more complete edition was edited by Nicholas Biddle and published in Philadelphia. But even then, it wasn’t the full story. Only in more recent years has the complete documentation been compiled and made accessible to the public.

By the time Lewis and Clark stepped off the trail in September 1806, they had traveled over 8,000 miles and changed the course of American history. What they brought back was more than just specimens and map. It was a fuller, more intricate picture of a continent alive with complexity, beauty, and contradiction.

Their journey marked a moment when the boundaries of the known world stretched wide open, and their footprints left a trail not only across the soil of the American West, but deep into the collective memory of a burgeoning nation. The land, the people, the wildlife, and the unknown. All of it was now, for the first time, drawn into a single, sweeping narrative of exploration.

And as the wide Missouri carried them home on that final stretch, their work was far from over. Our work was far from over. But for a brief moment, they had done what very few had done before them. They had stepped into the vast unknown and returned to tell the tale. What they set in motion, what Lewis and Clark set in motion, What they set in motion, what Lewis and Clark set in motion, would ripple across the continent of the United States of America for generations to come.

News

Why Sherman Begged Grant Not to Go to Washington

Why Sherman Begged Grant Not to Go to Washington March 1864. The Bernett House, Cincinnati, Ohio. Outside the city is…

What Patton’s CRAZY Daily Life Was Really Like on the Front Lines

What Patton’s CRAZY Daily Life Was Really Like on the Front Lines General George Patton believed war was chaos and…

Joe Frazier Was WINNING vs Ali in Manila — Then His Trainer Said “Sit Down, Son

Joe Frazier Was WINNING vs Ali in Manila — Then His Trainer Said “Sit Down, Son Manila, October 1st, 1975….

Frank Sinatra Ignored John Gotti at a Hollywood Diner—By Nightfall, Sinatra Wasn’t Smiling

Frank Sinatra Ignored John Gotti at a Hollywood Diner—By Nightfall, Sinatra Wasn’t Smiling Beverly Hills, California. February 14th, 1986. The…

Clint Eastwood’s Racist Insult to Muhammad Ali — What Happened Next Silenced Everyone

Clint Eastwood’s Racist Insult to Muhammad Ali — What Happened Next Silenced Everyone Los Angeles, California. The Beverly Hilton Hotel…

Brad Stevens Insulted John Wayne’s Acting—What Happened Next Changed His Life Forever

Brad Stevens Insulted John Wayne’s Acting—What Happened Next Changed His Life Forever Universal Studios Hollywood, August 15th, 1964. A tense…

End of content

No more pages to load