How Did Churchill React When Patton Achieved in a Day What Others Couldn’t in Weeks?

In the depths of March 1945, Winston Churchill found himself beneath London streets, standing in the reinforced war rooms with his gaze locked on a sprawling strategic map of Germany. The stark lighting overhead created dramatic shadows across the detailed markings as his attention remained fixed on the Ryan River.

That final massive natural obstacle separating the Allied forces from what remained of the Third Reich’s industrial core. He’d been waiting impatiently for what felt like an eternity, growing more frustrated with each passing week. His anticipation centered on Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery finally initiating Operation Plunder, what was being buil as the most extensively planned and precisely coordinated river crossing the military world had ever witnessed.

A staggering force of 1 million soldiers stood ready for deployment, supported by 4,000 artillery guns strategically placed along the western riverbank. The preparation had consumed countless months of exhaustive, detailed work. Then something unexpected happened. A telegram arrived from Supreme Headquarters.

An assistant hurried into the room with the message, and Churchill rapidly tore open the envelope with practiced efficient movements. The color immediately drained from his weathered face as he read the contents, leaving him visibly shaken. The message had come from General George S. patent sent just 24 hours earlier and it contained words that would reverberate through military chronicles for decades to come.

The message was devastatingly simple. Patton had already crossed the Rine. He’d accomplished this feat in complete silence under the cover of total darkness. While Montgomery continued methodically positioning his forces like chess pieces on a board, Patton had already executed his move and secured victory. Churchill’s reaction would expose the stark reality about two radically different philosophies of conducting warfare and winning battles.

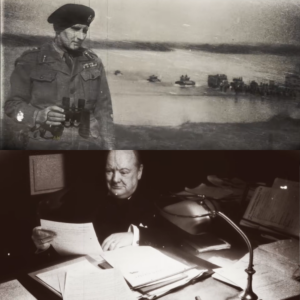

To properly grasp what transpired at the Rine, you need to understand the two commanders who shaped this historic moment. Bernard Law Montgomery and George Smith Patton Jr. Both men held the rank of general with substantial reputations and battlefield experience behind them. Both served in Allied uniforms fighting for the same ultimate goal.

But that’s where any resemblance between them ended entirely. Montgomery personified the quintessential British military establishment. Methodical in his approach, cautious in his planning, aristocratic in his demeanor and comportment. His core belief centered on the setpiece battle. The type of engagement where commanders control every variable, calculate every potential risk with precision, and verify every supply route before authorizing even a single shot.

His victory at Elamagne had been achieved through exactly this approach. Systematically grinding Raml into submission through superior numbers and relentless patient preparation. For Montgomery, warfare represented a precise science, a complex mathematical problem requiring careful solution. His philosophy rejected improvisation on the battlefield and unnecessary risk-taking.

Instead, he advocated for meticulous planning, thorough preparation, and striking with overwhelming force only when conditions reached absolute perfection. His troops affectionately knew him as Monty, though his detractors labeled him cautious to a fault and painfully slow. Patton represented the complete antithesis in every significant aspect.

A California native raised on romanticized stories of Confederate cavalry charges, he seemed like a 19th century warrior, somehow displaced into a 20th century conflict. He prominently wore ivory-handled revolvers on his belt and could recite ancient military campaigns from memory with passionate enthusiasm. His fundamental beliefs centered on speed, shock value, and the devastating impact of sheer audacity.

In Patton’s worldview, warfare wasn’t a scienced demanding calculation. It was an art form requiring practice with its canvas painted in blood and burning fuel. He’d driven his forces across France at unprecedented speed, his tank columns frequently outpacing their own supply trains and surviving on captured German fuel depots and supply stockpiles.

His operating philosophy could be stated simply but brutally. A good plan executed violently right now beats a perfect plan executed next week every single time. His troops practically worshiped him. His commanding officers feared his unpredictability, and Montgomery held him in complete contempt.

The animosity flowed equally strong in both directions. Patton openly mocked Montgomery, while Montgomery returned the favor with barely disguised disdain. But beneath their personal antagonism and professional competition lay something more substantial and far-reaching. A fundamental irreconcilable disagreement about proper military strategy and whether lives should be risked waiting for ideal conditions.

By March 1945, this philosophical conflict was about to face its ultimate test at Europe’s most dangerous and heavily fortified river. The Rine represented far more than just another barrier requiring passage. It served as the gateway to Germany’s industrial heartland in the Rur Valley, standing as the final natural defense before Allied armies could flood across and bring the war to its conclusion.

Hitler had personally commanded the destruction of every bridge without exception, the heavy fortification of every potential crossing point, and the transformation of every meter of the eastern bank into a lethal killing zone. Both Montgomery and Patton recognized that crossing the Rine would permanently define their military legacies and historical reputations.

One would accomplish it backed by an empire’s full resources and support, while the other would achieve it through nothing but bold audacity and nighttime cover. Operation Plunder, even its name, conveyed a sense of something ponderous and bureaucratic, sounding more like a committee creation than a warrior’s vision.

In many respects, that assessment was accurate. Montgomery had been developing his Rin crossing strategy since January, not for days or weeks, but for entire months of intensive preparation. He envisioned this operation as the pinnacle achievement of his distinguished military service. A river crossing so enormous and flawlessly executed that it would make the D-Day invasions appear modest by comparison.

The scale of forces involved was almost incomprehensible. 1 million soldiers from the British Second Army and American 9inth Army stood ready for deployment. 4,000 artillery pieces would transform the Rine’s Eastern Bank into a cratered moonlike landscape before a single infantryman stepped into an assault boat.

30,000 airborne troops would parachute and glide behind German defensive lines to establish and secure the bridge head. 3,000 bombers would systematically pulverize every German position within a 10-mi radius of the designated crossing sites. Montgomery demanded absolute supremacy and total control over every conceivable aspect of the operation.

Zero risk tolerance and zero possibility of failure. Achieving this perfect state of readiness demanded substantial time. Time to accumulate ammunition until literal mountains of shells formed in riverside storage dumps. time to rehearse each movement until his soldiers could execute the crossing unconsciously, and time to construct the massive bridges that would transport his armored divisions deep into Germany’s heartland.

Churchill observed this seemingly endless preparation with mounting impatience and increasing frustration. Each day of postponement represented another opportunity for Germans to strengthen their defensive positions, another chance for Hitler to redirect divisions eastward against the advancing Soviets.

And another day the war continued draining lives and precious resources. Eisenhower, serving as Supreme Allied Commander, shared this frustration with the glacial pace. He’d assigned Montgomery the Rine crossing operation as a gesture acknowledging British pride and international prestige, but he was beginning to seriously question whether Monty would ever actually initiate the assault.

By mid-March, the waiting had become almost intolerable for everyone involved in the planning. Montgomery had firmly established March 24th as his target date, assuring everyone that complete readiness would be achieved by then, every artillery piece in its designated position, every boat accounted for and tested, every conceivable risk identified and eliminated.

The massive buildup was impossible to conceal, visible from miles away in every direction. German reconnaissance planes flew overhead daily, systematically photographing the extensive supply dumps, the vast artillery concentrations, and the sprawling encampments housing thousands of waiting soldiers. The element of surprise had been completely sacrificed from the beginning.

German commanders knew precisely where Montgomery planned to cross, and they were reinforcing those specific positions with every available soldier they could spare from other threatened sectors. Montgomery remained unconcerned about the absence of surprise elements in his plan. He firmly believed tactical surprise was overrated and fundamentally unnecessary in modern warfare.

What truly mattered was deploying overwhelming crushing force. When he finally launched his attack, the German defenders would be annihilated beneath the sheer weight of concentrated British and American firepower, regardless of their preparation level. However, 200 miles to the south, George Patton wasn’t waiting for anything or anyone.

He’d been studying the rine with the patient, calculating focus of a predator stalking prey, and he’d identified a critical vulnerability in the German defensive network that Montgomery’s staff planners had completely missed or dismissed. Oppenheim, a small, seemingly insignificant German town situated on the Ryan’s east bank, positioned midway between mines and worms.

To Montgomery’s staff officers, it appeared strategically irrelevant, located too far south to impact Operation Plunder’s grand design. To Patton’s tactical mind, it represented everything he needed because Oppenheim was only lightly defended with minimal garrison forces. The Germans had redeployed most of their available troops northward to counter Montgomery’s obvious and impossible to conceal buildup.

They never imagined any American general would be sufficiently bold or reckless to attempt a major river crossing without massive preliminary preparation, without dedicated air support, and without the thunderous artillery bombardment that traditionally announced every significant military operation. Patton imagined precisely that scenario.

On the night of March 22nd, while Montgomery conducted yet another detailed briefing session with his commanders, meticulously reviewing plans for the hundth time, Patton struck with decisive action. No preliminary bombardment announced his intentions to alert defenders. No aerial bombing campaign softened enemy positions.

No smokec screen concealed troop movements, just profound silence and enveloping darkness, accompanied by six battalions of American infantry quietly boarding assault boats along the Rine’s western bank. At Oppenheim, the river stretched 300 yards across, fastm moving, bitterly cold, and defended by German machine gun positions and artillery imp placements commanding the high ground beyond.

Any rational military planner would have declared such an attempt suicidal without proper supporting fire preparation. Patton’s men went forward anyway without the slightest hesitation. They paddled across through the darkness in near complete silence. The only audible sounds being the gentle lapping of water against wooden boat hulls and the distant rumbling of Montgomery’s supply convoys 200 m northward.

German centuries detected nothing unusual until the initial boats scraped ground on the eastern shore. By that critical moment, effective German response had become impossible. Patton’s infantry assaulted the German defensive positions using bayonets and hand grenades, maintaining complete silence to preserve their precious surprise advantage.

Within two hours of the initial landing, they’d successfully secured a substantial bridge head. Within 6 hours, combat engineers were actively constructing a pontoon bridge across the river. Within 12 hours, Patton’s tank columns were rolling across the Rine straight into Germany’s heartland. Patton himself, standing on the Western Riverbank, observing his forces crossing, performed an act that would achieve legendary status in military folklore.

He walked out to the Pontoon Bridg’s center point, unzipped his trousers, and urinated directly into the Ry River. Then he turned toward his assembled staff officers and declared with evident satisfaction that he’d been anticipating this moment for a very long time. The following morning, he dispatched his now famous telegram to Eisenhower at Supreme Headquarters, announcing that without benefit of aerial bombardment, ground deployed smoke screens, artillery preparation, or airborne troop assistance, the Third Army had

successfully crossed the Rine. The message served as the military equivalent of a raised middle finger directed squarely at Montgomery. Patton’s crossing operation resulted in fewer than 40 total casualties. The German defenders were so thoroughly shocked and disoriented by the silent nocturnal assault that numerous positions surrendered without firing even a single defensive shot.

By the time Hitler’s Berlin headquarters comprehended what had occurred, Patton already had three complete divisions established across the river and was driving eastward at maximum possible speed. The sheer audacity of the accomplishment was absolutely breathtaking in its execution. While Montgomery continued carefully inventorying his artillery ammunition and reviewing operational plans, Patton had torn open the German front lines and was racing toward Frankfurt at full speed.

He’d accomplished everything Montgomery had repeatedly declared impossible, using only a fraction of the allocated resources, and in a fraction of the planned time. The telegram reached London during the early morning hours of March 23rd. Churchill remained awake, as he frequently was during these critical wartime periods, pacing restlessly through the underground war rooms.

An assistant rushed inside and presented him with the message from Eisenhower’s headquarters. Churchill read through it once rapidly, then again more deliberately and carefully. Then he began laughing, not with pleasant or joyful amusement, but with a bitter, incredulous bark that echoed off the concrete chamber walls.

He remarked to no one specifically that Patton had crossed the Rine without informing anyone beforehand. He studied the map spread before him, examining the colored pins marking Montgomery’s enormous buildup north of the rarer, the massive ammunition dumps and extensive artillery parks, and the airfields packed with bombers awaiting the attack order.

All of it remained waiting, still preparing for action, while Patton had already crossed and was actively advancing eastward. The implications were absolutely devastating for British military prestige. For months on end, Montgomery had insisted loudly and repeatedly that a Ryan crossing demanded massive, meticulous preparation, that anything less would prove suicidal, and that only a reckless fool would attempt it without overwhelming force superiority.

Patton had just proven him catastrophically and humiliatingly wrong in the most public manner imaginable. Using nothing more than a handful of assault boats and zero artillery preparation, Patton had achieved during one silent night what Montgomery hadn’t accomplished, despite a full month of highly visible buildup operations.

Churchill’s mood darkened considerably as the full implications settled in his mind. He dictated a message to Montgomery, his carefully chosen words dripping with unmistakable sarcasm. He wrote that the enemy had enjoyed catching them unprepared, pointedly referencing Montgomery’s continued delays.

Then, even more brutally, he suggested that events had moved faster than Montgomery’s careful preparations. The British High Command entered a state of complete shock and dismay. Montgomery’s entire strategic methodology had been constructed on the fundamental premise that the Rine represented an impregnable barrier without massive preliminary preparation.

Patton had just demolished that premise as false in the most public and embarrassing fashion imaginable. When Montgomery finally initiated Operation Plunder on March 24th, it delivered everything he’d promised and more. A thousand artillery guns firing in perfect synchronization, waves of bombers blackening the sky, masses of paratroopers descending behind enemy lines.

The spectacle was magnificent and overwhelming in its execution. And yet it was completely utterly unnecessary in achieving the strategic objective because Patton had already accomplished the mission using silence, speed, and pure tactical audacity. The British press attempted desperately to portray the events as a joint triumph, a combined Allied victory, but everyone involved understood the actual truth behind the propaganda.

Montgomery had been upstaged and overshadowed by the very general he’d spent years attempting to sideline and marginalize, and no amount of skillful propaganda could alter that fundamental reality. Churchill’s private comments to his closest adviserss proved even more scathing in their assessment. He informed his chiefs of staff that Montgomery had transformed the Rine Crossing into a ponderous bureaucratic setpiece operation when circumstances called for a daring, decisive stroke.

He openly questioned whether Britain’s methodical warfare approach remained suitable for modern mobile conflict dynamics. The humiliation Montgomery suffered was complete and total in every dimension. His crossing operation certainly succeeded in its objectives, but it would forever be remembered historically as the operation that came second, the operation that proved unnecessary.

Patton had stolen his thunder, his glory, and his rightful place in military history through one silent night of action on the Rine. History now remembers the Rine crossing as Patton’s finest operational hour and Montgomery’s greatest professional humiliation. However, the episode represented far more than merely a clash between oversized egos or a race for personal glory and recognition.

It delivered a fundamental lesson about how wars are actually won and how soldiers lives are ultimately saved or wasted. Montgomery’s approach appeared safer on paper and seemed more prudent from a planning perspective. Wait until you’ve assembled overwhelming force superiority. Eliminate every conceivable risk factor, then strike with such concentrated power that victory becomes mathematically inevitable.

But this apparent safety carried a hidden cost that isn’t always immediately apparent to planners. Every day Montgomery spent waiting represented another day for German forces to strengthen their defensive preparations, another opportunity to reinforce their positions, lay additional minefields, construct deeper bunkers, and position more artillery pieces.

When Operation Plunder finally launched its assault, Montgomery soldiers faced a fully prepared, deeply entrenched enemy force. The resulting casualties, while remaining acceptable by conventional military accounting standards, were substantially higher than strategically necessary. Patton’s approach represented the complete opposite tactical philosophy.

Strike fast and strike unexpectedly, never giving the enemy sufficient time to think, much less prepare proper defensive positions. His crossing at Oppenheim caught the German defenders completely offguard and totally unprepared for assault. The operation cost fewer than 40 casualties to secure a bridge head that would have demanded thousands of lives if the Germans had been ready and waiting with prepared defenses.

The strategic impact proved even more significant than the immediate tactical victory at the crossing point. Patton’s breakthrough completely collapsed the entire German defensive front south of the Ruer region. Within days of the crossing, his third army was racing across German territory, liberating towns and cities faster than military cgraphers could update their operational maps.

The German defenders, having concentrated their expectations on the main attack coming in the north with Montgomery’s forces, found themselves caught completely out of position strategically. Montgomery’s attack, when it finally materialized, encountered much stiffer resistance precisely because German commanders had anticipated and prepared for it.

The Germans had concentrated their best remaining combat units in the northern sector, fortified every defensive position with meticulous care, and prepared specifically for exactly the type of setpiece battle Montgomery preferred to fight. Churchill fully understood the lesson being delivered. In his post-war memoirs, he wrote about the Rine crossing operations with barely concealed frustration regarding Montgomery’s excessive delays and overpreparation.

He never explicitly criticized Monty in public forums as that would have been politically impossible given British morale considerations. However, his lavish praise for Patton’s boldness and tactical initiative spoke volumes about his true assessment. Eisenhower drew his own strategic conclusions from observing the Rin crossing operations.

Following these events, he increasingly assigned the decisive war-winning missions to American commanders who shared Patton’s fundamental philosophy of speed and aggressive action. Montgomery found himself progressively sidelined, receiving secondary objectives while American forces raced toward Berlin and ultimate victory.

The lesson wasn’t suggesting that planning holds no value or that caution always proves wrong in military operations. Elammagne had definitively proven that Montgomery’s methodical approach could win significant battles when properly applied. But the Rine crossing proved something more strategically important. That in warfare, timing matters equally as much as preparation quality.

That surprise can prove worth more than numerical superiority, and that calculated audacity can ultimately save more soldiers lives than excessive caution. Patton himself summarized the philosophy perfectly in a letter written to his wife shortly after completing the crossing. He wrote that his men had crossed the rine precisely because they never stopped to ask whether it was possible.

They simply went ahead and did it while others were still debating feasibility. Montgomery never publicly acknowledged that Patton had tactically outmaneuvered him on the rine, but explicit admission proved unnecessary. The silence of Patton’s crossing operation, the remarkable speed of his subsequent breakthrough, and the shock evident in Churchill’s voice when reading that telegram, all communicated louder than any formal admission ever could have.

In the final analysis, both commanders crossed the Rine successfully, and both contributed significantly to Germany’s ultimate defeat. However, only one of them accomplished it in a manner that fundamentally transformed how the world conceptualizes military leadership and strategic thinking. Only one commander proved conclusively that sometimes the optimal plan is the one executed before the enemy anticipates action.

That commander was George S. Patton. And the 24 hours he spent crossing the Rine in complete silence accomplished more strategically than Montgomery’s entire month of thunderous preparation ever could have achieved. If this story examining audacity versus caution and military leadership resonated with you, make sure to subscribe to WW2geear and activate that notification bell so you never miss our content.

We deliver untold stories of military leadership and decisive historical moments every single week. Drop a comment below and share your perspective. Was Patton’s calculated risk justified? Or should Montgomery’s careful, methodical approach have served as the preferred model? We appreciate you watching WW2 Gear and we’ll see you in the next video.

News

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene The coffee cup was…

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING June 18th, 1957,…

A Rival Spy Used a Wiretap on Gambino — He Found His Own Car Filled to the Roof With Expanding Foam

A Rival Spy Used a Wiretap on Gambino — He Found His Own Car Filled to the Roof With Expanding…

Dion O’Banion’s Men Pointed Guns at Al Capone in Church—Capone’s Response Made Him a LEGEND

Dion O’Banion’s Men Pointed Guns at Al Capone in Church—Capone’s Response Made Him a LEGEND They were burying Dion Oan,…

Fat Tony Salerno Ordered a $100K Hit on Bumpy Johnson — The Hitman Switched Sides

Fat Tony Salerno Ordered a $100K Hit on Bumpy Johnson — The Hitman Switched Sides Midnight March 15th, 1957, the…

John Wayne Noticed a Widow Sitting Alone at a Movie Premiere — What He Did Shocked Everyone Watching

John Wayne Noticed a Widow Sitting Alone at a Movie Premiere — What He Did Shocked Everyone Watching John Wayne…

End of content

No more pages to load