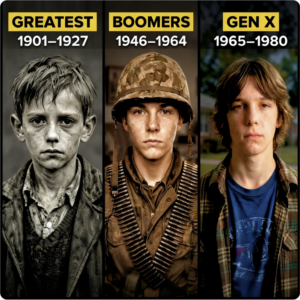

Psychology of Every Generation (1901 – 1980)

The Greatest Generation 1901-1927 Imagine being ten years old and watching your father lose everything. Not a job. Everything. The savings. The house. The certainty that tomorrow would be better than today. That was the Great Depression. And for the Greatest Generation, it wasn’t a chapter in a history book. It was childhood.

You learned early that the world didn’t owe you anything. You watched your parents stretch a single meal across three days. You wore your older brother’s shoes until your toes bent against the front. You didn’t ask for more, because you saw what more cost the people around you.

And then, just as you reached adulthood, the world asked for something else. It asked you to fight. World War II didn’t just define this generation. It forged them. 18-year-olds stormed beaches, 19-year-olds flew bombing missions over Europe, and the ones who stayed home rationed sugar, grew victory gardens and worked factory lines until their hands cracked.

Extreme, shared adversity does something to people. It hardens them. Not in a cold way, in a resilient way. But for the greatest generation, it wasn’t something they thought about. It was just life. This is why they don’t talk about their feelings. Not because they don’t have them, but because they came from a world where feelings were a luxury.

You didn’t process trauma. You buried it and kept moving, because there was a war to win, and a family to feed. This generation built something psychologists now call stoic pragmatism. The belief that hardship is inevitable, complaining is pointless, and the only thing that matters is what you do next.

And here’s what that gave them, an almost supernatural ability to endure. They could sit with uncertainty without spiralling, they could lose something meaningful and start over the next morning. They didn’t need the world to be fair, they just needed a clear task and the freedom to get it done. They carried it into the factories and boardrooms of post-war America.

They carried it into their marriages and their parenting. And whether they knew it or not, they passed it down, in smaller, diluted doses, to every generation that followed. The Silent Generation, 1928-1945 You were born into a world that was already on fire. The depression shaped your earliest memories. You remember your mother boiling the same bones twice to stretch a soup.

You remember your father leaving before sunrise and coming home with nothing. And if you were one of the millions in Oklahoma, Texas or Kansas, you remember the sky turning black in the middle of the day, dust storms so thick your mother put wet rags over your baby sister’s face just so she could breathe, families packing everything they owned into a truck and heading west on Route 66, only to be turned away at the California border.

You learned that silence was safer than asking questions, because the adults didn’t have answers either. And then the war came. You watched the men leave, brothers, cousins, neighbours. Some of them didn’t come back. You sat by the radio with your family, listening to reports from places you couldn’t find on a map, learning that the world was larger and more dangerous than anyone had told you.

By the time the war ended you’d already internalised the lesson. Keep your head down. Don’t make waves. The people who spoke up, who stood out, who questioned authority, you saw what happened to them. And then came McCarthy, and with him, the Red Scare. The Red Scare didn’t just target communists.

It targeted anyone who looked different, thought different, or asked the wrong questions. Teachers fired for what they read. Actors blacklisted for meetings they’d attended ten years earlier. Neighbours turning on neighbours. You learned that even in peacetime, the wrong word or the wrong friend could ruin your entire life. When keeping quiet keeps you safe, you learn to keep quiet.

It becomes instinct. For the silent generation, it wasn’t a strategy. It was survival. This is why they followed the rules. Not because they lacked imagination, but because they’d seen what happened to people who didn’t. They built their lives on stability, not self-expression. They took the secure job, married young, stayed put.

This created a generation with an unshakable reliability. Who clocked in early and never complained. Who fixed what was broken and didn’t wait for thanks. And while other generations raised their voices, they were the ones who kept the world turning. raised their voices, they were the ones who kept the world turning.

Baby Boomers You were born into victory. The war was over. The economy was booming. Your parents had survived the depression and fought the Nazis, and now they wanted one thing. A normal life. A house. A yard. Kids. Lots of kids. And so you arrived, 76 million of you, into a world that seemed to be expanding in every direction. New highways, new suburbs, new televisionsin every living room.

For the first time in decades the future looked like something to run toward, not something to survive. But underneath all that optimism there was a shadow. You grew up practising duck and cover drills beneath your school desk. You watched your parents track the Cuban Missile Crisis on the evening news, their faces tight with a fear they wouldn’t explain.

You learned that the world could end in a flash, literally, and that there was nothing you could do about it except keep living. And then the cracks started to show. You watched Walter Cronkite’s voice break when he announced JFK was dead. Four years later, Martin Luther King. Two months after that, Bobby Kennedy. Three assassinations in five years. Those as young as 18 got drafted into a war that didn’t make sense.

Vietnam wasn’t like World War II. There was no clear enemy, no front line, no moment of victory. Just jungles, guerrilla fighters and a government that kept saying we were winning while the body counts climbed every night on the evening news. It was the first war Americans watched from their living rooms.

And what they saw didn’t match what they were being told. Some of you went. Some of you marched against it. But all of you were shaped by it. By the realisation that the institutions your parents trusted might not deserve that trust. That kind of betrayal rewires how you see authority. For boomers, it wasn’t a headline – it was body bags on the evening news while the government promised victory was near.

But here’s the contradiction – the same generation that protested the system eventually ran it. The hippies became CEOs. The radicals became senators. The kids who marched for civil rights, women’s liberation and environmental protection grew up to build the most consumer-driven economy in history. They became experts at reinvention, at pivoting when the world shifted.

It’s why they’re still working, still leading, still refusing to step aside. They’ve been adapting their whole lives. Generation Jones, 1954-1965. If you were born in the late 50s or early 60s, you probably don’t recognise yourself in the boomer story. You didn’t march on Washington. You didn’t go to Woodstock.

You were 8, maybe 10 years old, watching it on TV in your living room. Too young to join, but old enough to believe it meant something. You came home from school to Brady Bunch optimism and dinner on the table. Your older siblings told you the world was changing, that anything was possible. You were a teenager when Nixon resigned.

You sat in front of the TV and watched a president lie about Watergate for two years, get caught on tape and resign before they could throw him out. Watergate wasn’t just a scandal, it was the moment you learned that sometimes the people in charge couldn’t be trusted. Your older siblings marched against the war, but by the time you were old enough to be drafted the war had already ended.

The cause that defined their generation wasn’t yours to fight. Then you turned 18. You were handed your driver’s licence just in time to sit in gas lines that stretched for blocks. The result of an oil embargo that brought America to its knees. You watched the news and heard words like stagflation, prices climbing while jobs vanished.

By the time you were ready to buy your first home, mortgage rates hit an all-time high at 18%. The older boomers had already bought houses, started careers and locked in their pensions. You got to watch from the outside, wondering what happened to the life you were promised. And that’s why they call you Generation Jones.

The generation that spent its whole life jonesing for something just out of reach. You had all the hope of the generation that spent its whole life jonesing for something just out of reach. You had all the hope of the generation before you but none of the timing. So you stopped waiting.

You took what was available, made it work and learned not to count on the world delivering what it promised. You became the bridge. You’re not boomers. You’re not Gen X. You’re the ones who fell through the cracks and built a life there anyway. Generation X You came home from school and the house was empty. No one texted to check on you. No one tracked your location.

You let yourself in with the key around your neck, made a snack and figured out the afternoon on your own. Maybe you watched TV. Maybe you rode your bike until the street lights came on. Maybe you watched TV. Maybe you rode your bike until the streetlights came on. Maybe you got into trouble and learned how to get yourself out of it. That was just childhood. Your parents were at work, which meant you were on your own.

And this wired something into you from an early age. You learned that you had to solve your own problemsbecause there was no one else around to solve them for you. This gave your generation something that kids today will never understand. True freedom. There was no GPS, no notifications, no one tracking where you were or when you’d be back.

You left the house on a Saturday morning and came home when the streetlights flickered on, and in between you were a ghost. You built forts in the woods. You biked to the next town just to see what was there. You played until your legs hurt and drank from the garden hose because going inside meant the day was over. If you made a mistake at 16, it stayed at 16.

No camera in every pocket, no screenshot, no permanent record of every dumb thing you said or did. You got to be young and stupid in private. And that gave you room to figure out who you were without the whole world watching. But it wasn’t all long summers and freedom. You saw things too. You watched your parents’ generation get hit, hard.

The early 80s recession. The stock market crash of 87. The layoffs and corporate downsizing that followed. You watched your parents sit at the kitchen table, voices low, bills spread out. You didn’t understand all of it, but you understood enough. By the time you entered the workforce in the early 90s, another recession was waiting for you.

You learned early that loyalty to a company didn’t mean the company would be loyal back. The job for life your parents believed in was already dying, and you knew it. This didn’t make Gen X lazy. It made them clear-eyed. You worked hard, but you didn’t confuse hard work with job security. You didn’t expect a gold watch or a pension.

You expected to earn your place every single day because you’d seen what happened to people who assumed they were safe. You kept your skills sharp and your resume ready. Not because you didn’t care, but because you’d learned the hard way that no one was going to look out for you, but you. Some people call it cynicism. For Gen X, it’s just reality.

You learned early that no one was coming to save you, so you saved yourself.

News

Why Sherman Begged Grant Not to Go to Washington

Why Sherman Begged Grant Not to Go to Washington March 1864. The Bernett House, Cincinnati, Ohio. Outside the city is…

What Patton’s CRAZY Daily Life Was Really Like on the Front Lines

What Patton’s CRAZY Daily Life Was Really Like on the Front Lines General George Patton believed war was chaos and…

Joe Frazier Was WINNING vs Ali in Manila — Then His Trainer Said “Sit Down, Son

Joe Frazier Was WINNING vs Ali in Manila — Then His Trainer Said “Sit Down, Son Manila, October 1st, 1975….

Frank Sinatra Ignored John Gotti at a Hollywood Diner—By Nightfall, Sinatra Wasn’t Smiling

Frank Sinatra Ignored John Gotti at a Hollywood Diner—By Nightfall, Sinatra Wasn’t Smiling Beverly Hills, California. February 14th, 1986. The…

Clint Eastwood’s Racist Insult to Muhammad Ali — What Happened Next Silenced Everyone

Clint Eastwood’s Racist Insult to Muhammad Ali — What Happened Next Silenced Everyone Los Angeles, California. The Beverly Hilton Hotel…

Brad Stevens Insulted John Wayne’s Acting—What Happened Next Changed His Life Forever

Brad Stevens Insulted John Wayne’s Acting—What Happened Next Changed His Life Forever Universal Studios Hollywood, August 15th, 1964. A tense…

End of content

No more pages to load