Sean Connery Got Ultimatum at 3 AM — Studio’s Power Move BACKFIRED Spectacularly

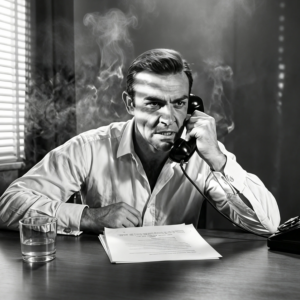

The phone rang at 3:00 a.m. in Shan Connory’s London flat, and the voice on the other end would destroy everything he thought he knew about his own career. It was October 1970. Shan Connory, global icon, the man who defined James Bond for an entire generation, sat in darkness holding a receiver that carried news no actor ever wants to hear.

The studio executives weren’t calling to negotiate. They weren’t calling to compromise. They were calling to deliver an ultimatum that would force Shawn to choose between his dignity and his livelihood. “We own you,” the voice said quietly. “And we own Bond. You can cooperate or you can disappear.” Shaun’s hand tightened on the receiver.

Outside his window, London slept peacefully, unaware that their most famous export was about to wage a war that would define not just his career, but the entire relationship between actors and the studios that created them. The caller was Cubby Broccoli, producer of the Bond franchise, and the words he spoke that night would echo through Hollywood for decades.

But what Broccoli didn’t know was that Shawn had been preparing for this conversation for 3 years. What he didn’t know was that the man on the other end of that phone line had already decided to risk everything. But nobody understood the price Shan Connory was willing to pay to own himself. Shan Connory was never supposed to be James Bond.

In 1961, he was a struggling Scottish actor with a thick accent, a background in manual labor, and exactly zero connections to the British establishment that Ian Fleming had envisioned for his sophisticated secret agent. The producers were looking for someone refined, educated, aristocratic. What they found was a 6.

2 2 former bodybuilder from Edinburgh’s workingclass fountainbridge district who had quit school at 13 to work in a coffin factory. The casting session that would change cinema history almost never happened. Shawn was in London, broke, sleeping on friends couches, taking whatever work he could find. He’d done some television, a few minor films, but nothing that suggested star potential.

His bank account held less than £50. His landlord was threatening eviction. His mother back in Edinburgh was writing letters asking when he’d give up this acting nonsense and find real work. When his agent mentioned the Bond audition, Shawn almost didn’t go. He was tired of rejection, tired of being told his accent was too thick, his background too rough, his look too unconventional for leading roles.

But something about the character intrigued him. James Bond was a killer, not a gentleman. Under all the sophistication and gadgets, Fleming had created someone who survived by violence and cunning. Shawn understood that. Growing up in Edinburgh’s tenementss, you learned to fight or you didn’t survive.

The audition took place at a nondescript office in Soho. Shawn walked in wearing his only decent suit borrowed from a friend and faced a panel of producers who looked like they’d rather be anywhere else. Cubby Broccoli, Harry Saltzman, and director Terrence Young sat behind a desk, skeptical and already running late.

“Can you handle action sequences?” Broccoli asked without looking up from Sha’s headsh shot. I can handle whatever needs handling, Shawn replied in an accent so thick the producers exchanged glances. What happened next lasted less than 2 minutes, but it would determine the next decade of Sha’s life. Terrence Young asked him to demonstrate how he’d approach a fight scene.

Shawn didn’t hesitate. He moved with a fluid violence that seemed to transform the room. His hands became weapons. His body became coiled steel. For those two minutes, he wasn’t an unemployed actor in a borrowed suit. He was something dangerous. The producers fell silent. They’d expected theatrical poses, stage combat, the kind of refined violence they’d seen in other auditions.

Instead, they witnessed something raw and authentic, something that suggested real menace beneath polished surface. “Where did you learn to move like that?” Young asked. the streets,” Shawn said simply. But nobody in that room understood what they’d just unleashed. The contract they offered him seemed like salvation.

£50,000 for three films with options for more. To a man who’d been earning less than £10 a week, it was unimaginable wealth. Shawn signed without reading the fine print, without understanding that he was selling more than his acting services. he was selling himself. The first Bond film, Dr. No, was shot on a shoestring budget with a cast of unknowns and a director fighting for every creative decision.

Shawn threw himself into the role with an intensity that surprised everyone, including himself. This wasn’t just another job. This was his chance to prove that a workingclass Scottish actor could embody sophistication without losing his edge. The transformation was remarkable. Shawn studied every aspect of the character, working with dialect coaches to refine his accent while maintainingits masculine authority, learning to wear expensive clothes like he’d been born to them, mastering the casual violence that made Bond lethal. He spent

hours perfecting the way Bond lit a cigarette, the way he ordered a martini, the way he killed without emotion. But beneath the surface, something else was happening. Shawn was discovering that playing James Bond required him to become someone else entirely. Not just on camera, but in life. The studio had expectations about how Bond should behave in public, how he should dress, who he should date, what he should say in interviews.

The film’s release in 1962 changed everything overnight. Suddenly Shan Connory was an international sensation. Women wanted him. Men wanted to be him. The studio executives who had been skeptical during casting were now calling him the most valuable property in entertainment. Magazine covers featured his face. Teenage girls screamed his name at premiieres.

He couldn’t walk down a street without being mobbed. But success came with a price nobody had explained. The studio owned his image. They controlled his public appearances. They decided which projects he could pursue and which he had to reject. Most importantly, they owned James Bond. And increasingly, they acted as though they owned Sha Connory, too.

The first sign of trouble came during negotiations for the second film, From Russia with Love. Shaun’s agent asked for a salary increase commensurate with the success of Dr. No. The film had made millions worldwide. Shaun’s performance was being praised by critics and audiences alike. Surely, he deserved more than the contracted amount.

The studio’s response was swift and brutal. Take what we’re offering or we’ll find another actor to play Bond. You’re replaceable, Broccoli told him during a tense meeting at Pinewood Studios. James Bond is not. Shawn stared at the man who had given him his biggest break and realized he’d made a deal with the devil.

The character that had made him famous was becoming his prison. Every public appearance was choreographed. Every interview was scripted. Every aspect of his life was subject to studio approval. When Shawn tried to take on other projects between Bond films, he was blocked. The studio claimed he might dilute the Bond brand.

When he expressed interest in dramatic roles, he was told that audiences wouldn’t accept James Bond in Shakespeare. When he criticized aspects of the scripts, he was reminded that actors act, they don’t write. But this was only the beginning of a war that would consume the next 8 years of his life. The studios control extended beyond just the Bond films.

They had approval over his other projects, his public statements, even his personal relationships. When photographers caught him with women who weren’t deemed suitable for Bon’s image, he was lectured about maintaining the character’s mystique. When he spoke about his workingclass background in interviews, he was told to emphasize Bond’s sophistication instead.

The pressure intensified with each film. Goldfinger in 1964 made him the highest paid actor in the world, but it also made him the most controlled. The studio monitored his interviews, scripted his public appearances, and threatened legal action when he deviated from their approved image.

Sha Connory, the person was disappearing behind James Bond, the brand. Between Goldfinger and Thunderball, Shawn experienced his first serious breakdown. The constant scrutiny, the inability to live his own life, the growing resentment toward the character that had made him rich but cost him his freedom, all combined into a crisis that few people knew about.

He spent 3 weeks in a private clinic officially for exhaustion, actually for what would now be recognized as severe anxiety and depression. But the studio machine didn’t stop. While Shawn recovered, they were already planning merchandise tie-ins, promotional campaigns, and product placements for the next film.

James Bond was becoming bigger than the man who played him, and that man was suffocating under the weight of his own creation. The breaking point came in 1967 during production of You Only Live Twice. Shawn was exhausted, creatively frustrated, and increasingly resentful of the studio’s control. The Japanese locations were grueling, the script was formulaic, and the producers seemed more interested in merchandise tie-ins than making a good film.

The working conditions were brutal. 16-hour days in sweltering heat. Dangerous stunts performed without proper safety measures. A director more concerned with spectacle than story. Shawn watched fellow actors get injured, saw crew members collapse from exhaustion, and realized the studio cared more about meeting their release date than protecting the people making the film.

But the final straw wasn’t professional. It was personal. Shawn had been quietly dating French actress Breijit Ober, a relationship he’d kept private to avoid media scrutiny. She was intelligent,independent, completely uninterested in his fame. For the first time since becoming Bond, Shawn felt like he could be himself with someone.

They talked about art, philosophy, life beyond the entertainment industry. She reminded him of who he’d been before the world knew his name. When paparazzi photos surfaced of them together in Tokyo, the studio’s reaction was immediate and vicious. They demanded he end the relationship, claiming it damaged Bon’s image as an available bachelor.

When Shawn refused, they threatened to destroy his career. “You belong to us,” Saltzman told him during a screaming match in his trailer. “Your private life belongs to us. Everything about you belongs to us until this contract expires.” Shawn looked at the man who was trying to control his heart and made a decision that would shock the entertainment world. I quit, he said quietly.

The silence that followed was deafening. Saltzman’s face went white. The assistant director who’d been listening outside the trailer door froze. In the distance, the sounds of filming continued. But inside that small space, everything had changed. “You can’t quit,” Saltzman said finally. “You have a contract.

” Sue me,” Shawn replied, and walked out of the trailer, off the set, and away from the character that had defined his life for 6 years. The announcement sent shock waves through Hollywood. Shan Connory, at the height of his fame, with millions of dollars in future earnings guaranteed, was walking away from James Bond. The studio executives were furious, the media was baffled, and fans were heartbroken.

Stock prices for the production companies dropped. Insurance companies scrambled to assess the financial damage. An entire industry built around one man’s portrayal of a fictional character suddenly faced extinction. But Shawn was free, or so he thought. The studio’s revenge was swift and systematic. They blocked him from major studio projects, spread rumors about his professionalism, and made it clear to other producers that hiring Sha Connory meant making an enemy of the most powerful franchise in entertainment. Phone calls were made,

favors were called in. Doors that had been open suddenly slammed shut. Shawn found himself effectively blacklisted from Hollywood’s biggest productions. Scripts he was interested in mysteriously went to other actors. Meetings were cancelled at the last minute. Agent stopped returning his calls. The message was clear.

Challenge the studio system and the studio system will destroy you. For 2 years, Shawn struggled to find work worthy of his talent. He took smaller films, independent projects, anything that would keep him acting and pay his bills. Some were good, most weren’t. all reminded him that he was no longer the most powerful actor in the world.

He was just another performer looking for his next job. The isolation was devastating. Friends in the industry were afraid to be seen with him. Social invitations dried up. The same people who had courted his attention when he was bonded now crossed the street to avoid him. Shawn learned that Hollywood friendships were often just business relationships in disguise.

During this period, he made some of the worst films of his career. Not because he wanted to, but because he had no choice. He needed money. He needed work. He needed to prove he could still draw audiences without the Bond name. Some of these films lost money. Others were barely released. All of them reinforced the studios narrative that Shan Connory without James Bond was worthless.

But something else was happening during these wilderness years. Shawn was rediscovering who he was beneath the character. He started reading again, something he’d had little time for during the Bond years. He traveled to places not connected to film promotions. He had conversations that weren’t interviews. Slowly, painfully, he began to remember the person he’d been before fame consumed his identity.

The phone calls started in 1969. Polite at first, then increasingly desperate. The Bond franchise was struggling without him. George Lasenby’s single film as Bond had disappointed at the box office and the studio was facing the possibility that they’d killed their golden goose. Box office receipts were down 40%.

Merchandise sales had plummeted. The franchise that had seemed invincible was suddenly vulnerable. We need you back, Broccoli said during one of many conversations. Name your price. But Shawn had learned something during his exile. He’d discovered that his power wasn’t just in his acting ability. It was in his willingness to walk away.

The studio needed him more than he needed them. They’d built an empire on his performance. And without him, that empire was crumbling. The negotiations for Diamonds Are Forever were unlike anything Hollywood had seen. Shawn didn’t just ask for more money. Though the salary he demanded was astronomical. He demanded creative control, script approval, and most importantly, a guarantee that this wouldbe his final Bond film.

He wanted control over his promotional appearances. He wanted approval over his leading lady. He wanted the right to walk off the set if working conditions became unacceptable. The studio, desperate to save the franchise, agreed to terms that would have been unthinkable 3 years earlier. Shawn would receive the highest salary ever paid to an actor, plus a percentage of the profits, plus complete creative control over his character.

It was a total capitulation by the studio system to an individual performer. Shawn returned to Bond in 1971, but he was a different man. Harder, more cynical, less willing to play the game. His performance in Diamonds Are Forever reflected this change. Bond was still sophisticated, still lethal. But there was something colder about him now, something that suggested the man behind the character had paid a price for his fame.

The film was a massive success, restoring the franchise’s profitability and proving that audiences still craved Shaun’s version of Bond. But Shawn honored his commitment. He walked away from Bond again, this time permanently, or so everyone believed. But the studio wasn’t finished with him yet. The legal battles continued for years.

The studio claimed Shawn had damaged their property by speaking critically about the films. They sued him for breach of contract, defamation, and interference with business relationships. Shawn counter sued for restraint of trade, invasion of privacy, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. The litigation consumed thousands of hours and millions of dollars, enriching only the lawyers involved.

Meanwhile, Shawn was rebuilding his career on his own terms. He chose projects based on artistic merit rather than commercial potential. He worked with directors who respected his intelligence and experience. Slowly, methodically, he was proving that he could be more than just Bond. In 1983, 12 years after Diamonds are Forever, Shawn received an offer that seemed impossible.

a rival studio backed by massive financial resources wanted him to play Bond again in a film that would compete directly with the official franchise. The money was astronomical. The creative freedom was absolute and the chance to thumb his nose at his former tormentors was irresistible. Never Say Never Again became more than just a film.

It became Shaun’s final statement about his relationship with the character that had defined his career. At 53, he was older than any previous Bond, but he brought a gravitas and worldweiness to the role that the younger actors couldn’t match. He was playing Bond as he’d always wanted to. Intelligent, experienced, human. The production was everything the previous Bond films hadn’t been.

The director consulted him on every major decision. The script incorporated his suggestions. He had control over his wardrobe, his dialogue, his action sequences. For the first time in over 20 years, Shawn was truly collaborating rather than just performing. The film was Shaun’s victory lap and his goodbye.

He’d proven that he could return to Bond on his own terms, make it successful, and walk away with his dignity intact. The studio that had once claimed to own him could only watch as he redefined their most valuable property one final time. But the real victory wasn’t financial. It was personal. Shawn had spent 20 years fighting for the right to control his own career, his own image, and his own life.

He’d walked away from guaranteed millions, endured professional exile, and risked everything he’d built. In the end, he’d won something more valuable than money, his freedom. The war had cost him relationships, opportunities, and years of his life. But it had also taught him something that no acting school could provide.

The importance of owning yourself in an industry designed to own you. The lessons of Sha Connory’s war with the studio system echoed through Hollywood for decades. Actors who had once accepted whatever terms they were offered began demanding more control over their careers. The absolute power of the studio system began to crumble as performers realized they had more leverage than they’d understood.

Today’s actors owe Sha Connory a debt they might not even realize. His willingness to sacrifice everything for autonomy created precedents that protect performers rights, creative input, and personal freedom. Every actor who has script approval, every performer who controls their image, every celebrity who can choose their projects owes something to the Scottish actor who refused to be owned.

Shawn never spoke publicly about the personal cost of his battles, the years of stress, the relationships strained by professional pressures, the constant fear that his career could be destroyed by men in boardrooms. He simply moved forward, choosing projects that interested him rather than those that would maximize his income.

In his later years, Shawn became something the studio executives had neverexpected. A respected dramatic actor whose bond years were just one chapter in a larger story. He won an Oscar for the untouchables, earned critical acclaim for complex roles in films like The Name of the Rose and Finding Forester, and became an elder statesman of cinema.

But those who knew him best understood that the man who emerged from the Bond Wars was fundamentally different from the eager young actor who had auditioned in that Soho office decades earlier. He’d learned that fame was a trap, that success could become a prison, and that the only way to maintain your integrity in Hollywood was to be willing to walk away from everything. The 3:00 a.m.

phone call that started this story was just one moment in a war that lasted decades. Shan Connory’s refusal to be owned, controlled, or diminished by the system that created him became a template for every actor who came after. His willingness to sacrifice short-term gain for long-term autonomy changed not just his own career, but the entire relationship between performers and the industry that needed them.

When Shan Connory died in 2020, the obituaries focused on his performances, his charm, and his contributions to cinema. But those who understood his true legacy, knew that his greatest achievement wasn’t playing James Bond. It was proving that no studio, no matter how powerful, could own a man who refused to be bought. The war was over.

Shawn had won.

News

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later Hong Kong,…

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory In 1943, the Chinese economy…

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office July 5th, 1945. Harry…

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene The coffee cup was…

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING June 18th, 1957,…

A Rival Spy Used a Wiretap on Gambino — He Found His Own Car Filled to the Roof With Expanding Foam

A Rival Spy Used a Wiretap on Gambino — He Found His Own Car Filled to the Roof With Expanding…

End of content

No more pages to load