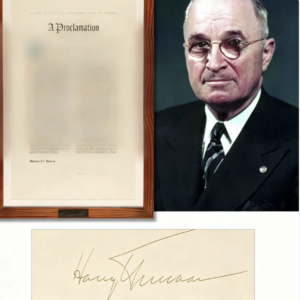

The Letter Roosevelt Wrote to Truman – So Insulting He Never Showed Anyone

April 12th, 1945. The time was 5:47 in the evening. Harry Truman had been president for exactly 2 hours and 12 minutes. He was sitting in what was now his office in the White House. He was still in shock from the speed of events. Roosevelt was dead. Truman was president. The world had changed in an instant.

Matthew Connelly entered the office. He would become Truman’s appointment secretary. He was carrying a sealed envelope. Mr. President, Connelly said. He was still getting used to addressing Truman that way. This was in the Resolute desk. It’s marked to be opened by my successor upon my death. It’s addressed to you. Truman took the envelope.

It was heavy cream colored stationery. This was the kind Roosevelt used for personal correspondence. Across the front, in Roosevelt’s own distinctive handwriting, it read to Harry S. Truman, Vice President of the United States, to be opened only upon assuming the presidency. Truman’s hands shook slightly as he broke the seal.

He expected some words of encouragement. Maybe some advice on how to handle the tremendous burden he was inheriting. What he found instead would haunt him for the rest of his life. The letter was dated March 28th, 1945. That was just 15 days before Roosevelt’s death. It was written in Roosevelt’s own hand.

His writing had become shaky and difficult to read, but the content was clear enough. Truman began reading. Dear Mr. Truman, if you are reading this, I am dead and you are now president of the United States. I write this not to welcome you to the office. I write this to record my honest assessment of the situation you have inherited.

And I write to record my assessment of your capacity to handle it. I owe you at least the truth. however unpleasant. Truman felt his stomach tighten. The tone was already wrong. This wasn’t a supportive letter from a dying president to his successor. This was something else. He continued reading. Let me be frank.

I never wanted you as my vice president. You were forced upon me by party bosses. They cared more about winning Missouri than about governing the country. I accepted you because I had no choice, not because I believed you were qualified for the role you might be called upon to fill. The last 82 days have done nothing to change my assessment.” Truman had to stop reading.

He put the letter down. He walked to the window trying to control his breathing. Roosevelt’s first words to him as president were to say he was never wanted. He was told he wasn’t qualified. Truman stood there for several minutes. Then he forced himself to return to the desk. He had to continue reading.

He had to know what else Roosevelt had written. You lack the intellectual capacity for this job. You lack the worldly experience. You lack the personal sophistication required to be an effective president. This is especially true during this critical period in history. You have spent your entire political career as a creature of the Pendergast machine in Missouri.

You were a county judge who stumbled into the Senate. You got there through luck and political connections, not through merit. Your tenure in the Senate had some modest accomplishments, but it demonstrated the limits of your capabilities. You are a small town politician. You have been suddenly thrust into global responsibilities you cannot comprehend.

Truman’s face was burning. Roosevelt was systematically dismantling him. He was attacking his background, his intelligence, his entire career. But the letter continued and it got worse. I have deliberately kept you uninformed about critical matters of state. This was not an oversight. It was a conscious decision.

It was based on my judgment. I decided you lacked the sophistication to understand these matters. I decided you lacked the discretion to handle them properly. the Manhattan Project, our agreements with Churchill and Stalin, the complex diplomatic arrangements that will shape the postwar world. I did not brief you on these matters.

I did not trust your judgment regarding them. So, it was true Roosevelt had deliberately excluded him. It wasn’t because of security concerns. It wasn’t because of time constraints. It was because Roosevelt believed Truman was too stupid to be trusted with the information. Truman felt a wave of humiliation.

Then a wave of rage washed over him. He wanted to stop reading. He wanted to burn the letter and never think of it again. But he forced himself to continue. He needed to know everything Roosevelt had thought about him. You will find yourself lost. You will be lost in the complexity of the challenges facing this nation. You lack the education to understand the nuances of international relations.

You lack the strategic thinking to navigate the peace that must follow this war. You lack the political skill to manage the domestic transitions that will be necessary. I would spare you this burden if I could. But death has made that impossible. So you must stumble forward.

Hopefully youwill have enough sense to listen to your advisers. Do not trust your own inadequate judgment. Roosevelt thought he was a bumbling fool. He thought Truman needed to be controlled by his advisers. The contempt was overwhelming. But there was more. Eleanor and I have discussed at length what will happen when you become president. She shares my concerns about your capacity for the office. We have made arrangements.

We have made arrangements to ensure that people of actual competence will guide you. Listen to them. Do not imagine that your provincial common sense is adequate for the challenges you will face. You are not equipped to make major decisions independently. Truman’s hands were shaking so badly he could barely hold the paper.

Roosevelt and Eleanor had discussed his inadequacy together. They had made arrangements to control him as president. The letter was becoming more than an insult. It was evidence of a conspiracy. It was a plan to manage and manipulate him as president. Truman read on. I write this knowing it will wound you, but better a wounded ego than a failed presidency.

You need to understand your limitations, Mr. Truman. You need to recognize that you are not capable of filling my shoes. You are not capable of leading this nation through the challenges ahead. Your role is to maintain stability. Your role is to stay in place while better men make the actual decisions.

Better men. Roosevelt believed there were better men who should make decisions. Truman should just serve as a figurehead. This wasn’t just contempt. This was an explicit instruction. Truman should not actually govern as president. Roosevelt was trying to control his successor from beyond the grave. He wanted to ensure that even in death, Roosevelt’s vision would prevail over Truman’s judgment.

The letter continued with specific instructions. This part was about the Soviet Union. You must maintain the alliance with Stalin at all costs. I have worked for years to build a relationship of trust with him. Your instincts will be to take a harder line. Ignore those instincts. You lack the understanding of Stalin’s psychology.

You lack my understanding of Soviet interests. Listen to those who were close to me. Follow the path I have established. Roosevelt was commanding Truman to follow his policies on the Soviet Union. He was dismissing in advance any concerns Truman might have. But Roosevelt’s assessment of Stalin was already proving catastrophically wrong.

The Soviets were breaking promises made at Yalta. They were consolidating control over Eastern Europe. Truman would have to deal with this reality, but Roosevelt was telling him to ignore it. He was telling him to blindly follow Roosevelt’s failed approach. Then the letter turned to the atomic bomb. If this weapon is completed before the war ends, you will face a decision.

You will have to decide whether to use it. I have deliberately not prepared you for this decision. It requires wisdom and moral clarity. You do not possess these qualities. Consult extensively with your scientific and military advisers. Do not trust your own judgment on a matter of this magnitude.

you are not equipped to make such a decision independently. Roosevelt had kept Truman ignorant about the atomic bomb. He did this precisely so that Truman would feel unprepared. He wanted Truman to have to rely on others. It was a deliberate strategy. The goal was to ensure Truman wouldn’t trust himself.

He wouldn’t trust himself to make the most important decision any president had ever faced. The cruelty was breathtaking. The manipulation was stunning. The letter turned to domestic policy. Do not attempt to dismantle what I have built. The New Deal represents the achievements of my 12 years in office. You lack the vision to improve upon it.

You lack the political skill to build anything comparable. Your role is to preserve my legacy. Your role is not to establish your own. You are a caretaker president. You are maintaining what greater men have created. Roosevelt was explicitly telling him he was incapable. He was saying Truman couldn’t be anything more than a caretaker. He was saying Truman shouldn’t try to accomplish anything.

He lacked the ability to succeed. It was a devastating psychological attack. It was designed to undermine Truman’s confidence. It was meant to crush his ambition from the very first moment of his presidency. The letter’s conclusion was the most insulting part. I do not write this out of personal animosity, Mr. Truman. I write it out of love for this country.

You are simply not the man this moment requires. History will judge you harshly, as it should. My only hope is this. I hope the structures I have put in place will be strong enough. They must withstand your inadequacy. I hope the men I have empowered will be able to guide you. They must guide you away from the worst decisions.

They must save you from the decisions your limitations might lead you toward. God help Americafor you cannot. Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Truman finished reading. He sat in stunned silence. God help America for you cannot. Those were Roosevelt’s final written words to him. Not encouragement, not advice, not even basic respect.

It was just a brutal condemnation. Roosevelt said Truman was unqualified. He said he was unintelligent. He said he was incapable. Roosevelt had used his dying days to write this letter. It was designed to destroy Truman’s confidence. It was meant to established that he should be a puppet president. He would be controlled by Roosevelt’s loyalists.

Truman stood up. He walked around the office for several minutes. The letter was still in his hand. He was experiencing waves of different emotions. There was humiliation, there was rage, there was determination, and there was a cold, clarifying anger. Finally, he called Connelly back into the office. Matthew, was anyone else aware of this letter? Connelly shook his head. No, Mr.

President. It was sealed in the desk. I don’t believe anyone else knew it existed. Truman made a decision immediately. This letter will never be seen by anyone else. Not Eleanor Roosevelt, not the cabinet, not historians, not anyone. I’m locking it in my personal safe. It will stay there until I’m dead.

And even then, I’m writing instructions. It should remain sealed for 50 years after my death. Do you understand? Connelly nodded. Yes, Mr. President. But sir, why not destroy it? Truman’s answer revealed his character because it’s evidence. It’s evidence of what Roosevelt really thought. It’s proof that he deliberately sabotaged my ability to succeed as president.

Someday historians might need to understand that. But not now. Not while I’m trying to govern. This letter is Roosevelt’s final attempt to destroy me. I won’t let it succeed by making it public. But I won’t let him erase the evidence either. Over the next days and weeks, as Truman began to govern, Roosevelt’s letter echoed in his mind. It became a constant bitter whisper in his thoughts.

Every time someone suggested President Roosevelt would have done it this way, Truman remembered the letter. He remembered being called incapable. Every time an adviser implied Truman should just maintain Roosevelt’s legacy, he thought about being told he was merely a caretaker. The letter had been intended to break him.

Instead, it forged him into something stronger. It hardened his resolve. Truman made a silent, private decision. He decided that everything Roosevelt had told him to do, he would consider doing the opposite. Roosevelt had said maintain the alliance with Stalin at all costs. So, when the Soviets began to break their promises, Truman took a hard line.

He confronted Soviet expansion. Roosevelt had said, “Don’t trust your own judgment on the atomic bomb.” So Truman studied the issue with intense care. He consulted his advisers, but in the end, he made his own decision. He trusted his own mind. Roosevelt had said, “Preserve the New Deal and build nothing new.

” So Truman launched new programs. He called it the Fair Deal. He integrated the armed forces by executive order. He worked to establish his own domestic legacy. He refused to be just a caretaker, but the letter affected him deeply. It left psychological wounds that lasted his entire presidency. In private moments when a decision went badly or when the criticism was especially harsh, Truman would think about Roosevelt’s words.

You lack the intellectual capacity. You are not equipped. History will judge you harshly. The letter had planted seeds of doubt. Truman had to fight against those seeds every single day. He told himself over and over that Roosevelt had been wrong. But the words still hurt. They still stung. In June of 1945, Truman confided in his wife, Bess.

He was at his home in Independence, Missouri. It was one of the few times he felt he could be completely open. He showed her the letter. She was the only person he ever allowed to read it. Bess was furious. Her face grew pale, then flushed with anger as she read. Harry,” she said, her voice tight. “This is one of the crulest things I have ever read.

” Franklin Roosevelt was a vicious, petty man to write something like this. You must never let anyone else see it. It would destroy his reputation, but more importantly, it would hurt you. People would pity you, and you cannot govern effectively if you are an object of pity.” Truman agreed completely. The letter would remain their secret.

But then Bess asked him a perceptive question. It was a question that went right to the heart of the matter. Harry, she said, looking him directly in the eyes. Are you going to let this letter define how you see yourself? Are you going to spend your entire presidency trying to prove Franklin Roosevelt wrong? Truman thought about that for a long time.

The silence in the room was heavy. Finally, he answered, “No,” he said. I’m going to forget Roosevelt’s opinion. I am going to be the presidentI think this country needs. If that proves him wrong, fine. If it doesn’t, at least I will have been true to myself. I won’t be living under his shadow. But forgetting Roosevelt’s words was easier said than done.

The ghost of the former president was everywhere. In July of 1945, Truman traveled to Germany for the Potdam conference. This was his first face-to-face meeting with Stalin. He remembered Roosevelt’s letter. The letter said he lacked the sophistication to handle the Soviet leader. So Truman deliberately took a firmer line than Roosevelt ever had.

He did this partly because he believed it was the right thing to do on the merits. But he also did it to prove Roosevelt wrong. When Stalin responded to Truman’s firmness with a new respect, Truman felt a sharp sense of vindication. Roosevelt’s first prediction had been wrong. Truman could handle Stalin.

In August, Truman faced the most terrible decision any president had ever faced. He had to decide whether to use the new atomic bomb on Japan. He remembered the letter perfectly. Roosevelt had said he lacked the wisdom and moral clarity for such a decision. So Truman approached the choice with extreme care.

He consulted his advisers extensively. He weighed the options. He thought about the lives of American soldiers. He thought about the lives of Japanese civilians. But in the end, he did not pass the burden to someone else. He made the decision himself. He trusted his own judgment. Whether history would judge the decision as right or wrong, it was his.

He had refused to be the puppet President Roosevelt had intended him to be. Throughout 1946 and 1947, Truman began to build a new American foreign policy. The Soviet Union was becoming more aggressive. Europe was in ruins. Truman developed what became known as the Truman Doctrine. It was a promise to support free peoples resisting takeover.

Then came the Marshall Plan, a massive program to help rebuild Europe. These were new frameworks. They went far beyond anything Roosevelt had envisioned. Again, Truman was proving Roosevelt wrong. He was establishing that he was more than just a caretaker. He was a builder. He was a leader. But the letter also made him paranoid.

He became suspicious of anyone who had been too close to Roosevelt. Were they part of the arrangements Roosevelt had mentioned? Were they there to control him, to manage him? This suspicion contributed to Truman’s systematic purge of Roosevelt’s people from his administration. He needed advisers who were loyal to him.

He needed men who were loyal to President Truman, not to the memory of President Roosevelt. He could not tolerate the idea of being a figurehead. In 1948, Truman was running for president in his own right. The letter haunted him in a new way. Everywhere he went, political experts and newspaper columnists said he couldn’t win.

They said he wasn’t up to the job. They said he was inadequate. They were saying the same things Roosevelt had written in that terrible letter. Truman’s famous Give M hell campaign was fueled by many things, but partly it was about proving all those doubters wrong. It was about proving Roosevelt’s ghost wrong. On election night, the Chicago Tribune famously printed the headline, “Dwey defeats Truman.” But the headline was wrong.

Truman had won. He had won in a stunning historic upset. One of his first private thoughts in that moment of triumph was a direct answer to the letter. Roosevelt said, “I was incapable.” He thought he was wrong. I did this myself. Sometime in 1950, Eleanor Roosevelt learned about the letter’s existence.

Truman never showed it to her. She would never see its contents, but she came to the White House to discuss United Nations matters. During their conversation, she mentioned something casually. She said that Franklin had told her he was leaving a letter for Truman. She asked if Harry had found it.

She asked what Franklin had written. Truman’s response was cold and final. I found it, he said. I am not discussing its contents. But I will say this, Elellanor, your husband’s final words to me were not kind. They were not helpful. They revealed aspects of his character I wish I didn’t know about. Eleanor pressed him.

She wanted to know more, but Truman refused to elaborate. He would not say another word about it. Later, Eleanor wrote about the encounter in her diary. Her words showed her insight. She wrote, “Harry found Franklin’s letter, and clearly it upset him greatly. I fear Franklin may have been too honest about his concerns regarding Harry’s capabilities.

Franklin could be cruel when he thought he was being truthful. I suspect his letter to Harry was one of those cruel truths that didn’t need to be spoken. Certainly not from beyond the grave. In the years after he left the White House, Truman occasionally referenced the letter, but he was always careful.

He never revealed what it said. In a 1960 interview, a reporter asked him about his relationship with Roosevelt. Trumansaid, “Roosevelt left me a letter. I’ve never shown it to anyone except Bess. It revealed what he really thought about me, and it revealed what he thought about the presidency.” He paused, choosing his words with care.

Let’s just say it wasn’t encouraging. It wasn’t supportive. It was designed to undermine my confidence. It was meant to establish that I should be controlled by others. It didn’t work. I decided to ignore his advice. I decided to be my own man. The interviewer, of course, wanted more details. He asked what the letter contained, but Truman shut him down.

The letter will be sealed, he said firmly. It will be sealed for decades after my death. Someday historians can read it. They can judge for themselves. But I will say this. Roosevelt’s opinion of me was wrong. History is already proving that. I may not have been the president he wanted, but I was the president the country needed, and I did the job my way, not his.

In his final years, Truman wrote a private memorandum. He instructed that this memo be included with the letter when it was eventually unsealed. It was his final word on the matter. The memo read, “Franklyn Roosevelt wrote me this letter. He intended to break my spirit. He wanted to establish that I should be a puppet president.

He wanted me to be controlled by his people and his policies. He failed. I read this letter on my first day as president. I decided immediately that I would ignore everything in it.” Roosevelt thought I was stupid. He thought I was unsophisticated. He thought I was incapable. He was wrong. I proved him wrong through 8 years of consequential leadership.

This letter reveals more about Roosevelt’s character than it does about mine. He was a great president in many ways, but he was also capable of extraordinary cruelty. This letter is the evidence of that cruelty. The letter remained sealed in Truman’s personal papers. It stayed there for decades just as he had instructed.

It was not opened until 1992. That was 50 years after his death. When historians finally read it, the reaction was shock. There was outrage. Roosevelt’s reputation took a significant hit. The letter exposed a side of him that contradicted his public image. The public saw a benevolent leader. The letter showed a petty, cruel, and manipulative man.

It showed a man who deliberately tried to sabotage his own successor. He did it out of pure contempt. But the letter also cast Truman in a new light. Historians finally understood. Truman had governed for 8 years carrying a terrible burden. He carried the burden of Roosevelt’s devastating final words. He had risen above that psychological assault.

He had become an effective and consequential president. Every achievement of his presidency had been accomplished while fighting against Roosevelt’s prediction of his failure. This realization made Truman’s accomplishments seem even more impressive. He had succeeded despite being told by his predecessor that he was incapable of success.

Modern psychologists have since analyzed the letter. They note its cruel sophistication. Roosevelt knew exactly how to undermine a person psychologically. He attacked Truman’s intelligence, his background, and his capabilities. Then he framed the attack as an honest assessment. This created maximum psychological damage.

The letter was designed to make Truman doubt himself. It was meant to make him dependent on Roosevelt’s advisers. It was meant to prevent him from trusting his own judgment. It was in effect psychological warfare, and it was waged against his own successor. But Roosevelt miscalculated. He assumed Truman would be broken by the letter.

He thought Truman would internalize the criticism. He believed Truman would become the puppet he intended. Instead, Truman used the letter as motivation. Every word of contempt became fuel. It fueled Truman’s determination to prove Roosevelt wrong. In trying to destroy Harry Truman, Roosevelt accidentally forged him.

He forged him into a more independent and more determined leader. The letter Roosevelt left for Truman was so insulting that Truman never showed it to anyone during his lifetime except his wife. It was a final cruel message from a dying president to his successor. It was designed to break him psychologically.

It was meant to control him from beyond the grave. It failed. Truman read Roosevelt’s contemptuous words. He felt the intended pain and then he made a conscious decision. He decided to prove every single word wrong. and he did. History has judged Truman far more kindly than Roosevelt predicted. The letter stands today as evidence, but it is not evidence of Truman’s inadequacy.

It is evidence of Roosevelt’s capacity for cruelty, and it is lasting evidence of Truman’s profound strength. The weight of the letter never truly left him. It became a part of his presidency, a dark thread woven into the fabric of his daily life. When he faced the monumental decision to recognize the new state of Israel in 1948, the ghostof Roosevelt’s words hovered nearby.

You lack the worldly experience. You are not equipped to make major decisions independently. His Secretary of State, George Marshall, a man Truman deeply respected, was adamantly opposed. Marshall believed recognizing Israel would destabilize the entire Middle East and threaten vital oil supplies. He warned Truman it was a political move that would cost him the election.

The pressure was immense. It was exactly the kind of complex global situation Roosevelt had said would overwhelm him. But Truman thought of the survivors of the Holocaust. He thought of the moral imperative. He remembered Roosevelt’s command to simply listen to his betters. So he listened to Marshall’s council, weighed it carefully, and then trusted his own gut.

He made the decision to recognize Israel, believing it was the right thing to do. It was a decision made not in defiance of his advisers but in consultation with them yet ultimately trusting his own judgment. It was the act of a president not a puppet. The letter also shaped his relationships in profound and sometimes painful ways.

His distrust of the old Roosevelt circle meant he often surrounded himself with men of lesser stature but greater personal loyalty. This sometimes led to accusations of cronyism of building a Missouri gang. When old friends from his Senate days were appointed to positions, critics would sneer, pointing to Roosevelt’s assessment of him as a small town politician.

The letter had given his enemies a weapon, even if they didn’t know it existed. During the difficult years of the Korean War, when the conflict bogged down into a bloody stalemate, and his approval ratings plummeted, the whispers started again. The same doubts Roosevelt had planted were now being voiced in newspapers and on radio shows.

Is Truman in over his head? Does he have the capacity for this? In his most private moments, the fatigue and frustration were overwhelming. The letter was a wound that never fully healed, and the criticism of the nation picked at the scab. His decision to fire General Douglas MacArthur was the ultimate test of this internal struggle.

MacArthur was a national hero, a towering figure of American military might. He publicly challenged Truman’s policy of a limited war, wanting to expand the conflict into China. The political firestorm was incredible. To fire him seemed like political suicide. It was the kind of bold unilateral move that Roosevelt’s letter insisted he was incapable of handling wisely. Truman knew the risks.

He knew he would be vilified. But he also knew a fundamental principle of American democracy was at stake. Civilian control over the military. He could not let a general, no matter how popular, dictate foreign policy. The decision was his alone. He thought of the letter of being told he was a mere caretaker. Then he made the call.

He fired MacArthur. The country erupted in outrage. But Truman stood firm. It was in many ways the purest expression of his presidency. A difficult unpopular decision made because he believed it was right for the country regardless of the personal cost. He was leading, not just presiding.

After he left the White House and returned to independence, the letter’s shadow grew longer in some ways, but lighter in others. He was free from the daily burden of presidential decisions, but he now had to live with his legacy. In interviews and while planning his presidential library, he was constantly asked to reflect on Roosevelt to compare their administrations.

He was always gracious in public, always giving Roosevelt credit for his leadership during the depression and the war. But those close to him could see the subtle tightening of his jaw, the brief flash in his eyes. He was guarding the secret, maintaining the lie of a smooth and supportive transition out of a sense of duty to the office and perhaps to the country’s memory of Franklin Roosevelt.

He once told a close friend in the strictest confidence. I saved that man’s reputation. I carried the truth about him so the country wouldn’t have to. He saw his silence not as a personal failing but as a final presidential act absorbing a poison to protect the institution of the presidency itself. When he gave the go-ahad for the construction of his library, he was very specific about his papers.

He meticulously organized them, wanting historians to have a clear record, and he gave strict repeated instructions about that one specific envelope. 50 years, not a day sooner. He was ensuring that the truth would eventually come out, but only after the dust of history had settled, after the urgent needs of the nation had passed.

It was a controlled release of the truth, typical of the careful, deliberate man he was. In his final days, his mind would sometimes wander to those early hours of his presidency, the shock of Roosevelt’s death, the overwhelming weight of the war, and then the profound personal betrayal of that letter.

He had confidedto his daughter Margaret that the moment he finished reading it, he felt more alone than at any other time in his life. He was standing in the most powerful office in the world, and he had never felt weaker. But that feeling, he said, was also the making of him. It either breaks you or it makes you, he told her. And I was not in a breaking mood.

The letter forced him to confront his own insecurities headon. From the very first moment, there was no grace period, no gentle on boarding. He was thrown into the deepest end with an anchor of contempt tied to his leg. He had to learn to swim against its drag immediately. When Harry S. Truman died on December 26th, 1972, the secret of the letter remained safe with Bess and a handful of trusted archavists.

The public eulogies spoke of his plain-speaking honesty, his gutsy decisions, his unexpected rise to greatness. They spoke of the atom bomb, the Marshall Plan, the Truman Doctrine, and the integration of the military. They painted a picture of a man who grew into the office in a way no one could have predicted.

They were right, but they didn’t know the half of it. They didn’t know that the very engine of that growth, the fire that forged that determination, was a document of pure, undiluted contempt from the man he succeeded. The public Harry Truman was the man who asked for a one-way street sign for his desk that read, “The buck stops here.

” The private Harry Truman was the man who had to build that desk himself. From the shattered pieces of his confidence, using Roosevelt’s cruel letter as the blueprint, the 50-year clock started ticking. The world moved on through Vietnam, Watergate, the end of the Cold War. Historians continued to debate and reassess Truman’s legacy, his stature growing with each passing year.

And all the while in a climate controlled vault, the cream colored envelope waited.

News

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office July 5th, 1945. Harry…

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene The coffee cup was…

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING June 18th, 1957,…

A Rival Spy Used a Wiretap on Gambino — He Found His Own Car Filled to the Roof With Expanding Foam

A Rival Spy Used a Wiretap on Gambino — He Found His Own Car Filled to the Roof With Expanding…

Dion O’Banion’s Men Pointed Guns at Al Capone in Church—Capone’s Response Made Him a LEGEND

Dion O’Banion’s Men Pointed Guns at Al Capone in Church—Capone’s Response Made Him a LEGEND They were burying Dion Oan,…

Fat Tony Salerno Ordered a $100K Hit on Bumpy Johnson — The Hitman Switched Sides

Fat Tony Salerno Ordered a $100K Hit on Bumpy Johnson — The Hitman Switched Sides Midnight March 15th, 1957, the…

End of content

No more pages to load