Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office

July 5th, 1945. Harry Truman sat in the Oval Office reading a letter that made his jaw tighten. Henry Morganthaw Jr. Roosevelt’s Treasury Secretary for the past 11 years had just delivered an ultimatum. Morganthaw insisted on attending the Potam conference with the Allied leaders. If Truman refused to include him, Morganthaw would resign immediately.

Truman’s chief of staff waited for the explosion. Everyone knew what happened when someone tried to threaten Harry Truman. But Truman didn’t explode. He picked up his pen and wrote a single sentence on White House stationary. Your resignation is accepted effective immediately. He handed it to his secretary and said, “Isue this to the press within the hour.

” Morganthaw had walked into that office expecting negotiation. Instead, Truman had just ended an 11-year career with one sentence. Think about that response. Harry Truman, president for less than three months, had just fired Franklin Roosevelt’s closest friend without hesitation. Matthew Connelly wasn’t surprised by Truman’s decision.

He had been keeping a file on Morgan Thaw’s behavior since Roosevelt’s death on April 12th. The policy meetings Morganthaw held without informing the president. The treasury memos that undermined Truman’s economic decisions. The constant invocation of what Roosevelt would have wanted. Connelly told Truman that Morganthaw was making the entire administration look weak.

Truman looked at Connelly with cold satisfaction and said, “He just made it easy for me.” Connelly left that office knowing Truman had been waiting for this moment. And Morganthaw had just given him the perfect excuse. But what Morganthaw didn’t know was that his ultimatum had just triggered the confrontation Truman had been planning for months.

Because Morganthaw wasn’t just clinging to Roosevelt’s legacy anymore. He was actively sabotaging Truman’s presidency. And Truman had decided that Roosevelt’s ghost would no longer run the Treasury Department. Henry Morganthaw Jr. entered Franklin Roosevelt’s world in 1913 with wealth, ambition, and absolutely no government experience.

His father was Henry Morganthaw Senior, a successful real estate developer who would become ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. The family had money stretching back three generations. But Morganthaw was different from the entitled sons of New York’s elite around him. He had dropped out of Cornell University after 3 years to buy a farm in Duchess County, New York.

Most wealthy young men would have hired farm managers and played gentleman farmer on weekends. Morganthaw lived on that farm. He studied agricultural science. He experimented with crop rotation and livestock breeding. He worked the land himself. And in 1913, he bought the property next door to Franklin Roosevelt’s Hyde Park estate. Roosevelt was a rising state politician.

Morganthaw was an amateur farmer with progressive ideals. They became neighbors, then friends, then something closer than friends. For 30 years, Henry Morganthaw and Franklin Roosevelt were inseparable. When Roosevelt contracted polio in 1921, Morganthaw visited every week.

When Roosevelt became governor of New York in 1928, Morganthaw became his agricultural adviser. Their wives became best friends. Eleanor Morganthaw and Eleanor Roosevelt rode horses together in Rock Creek Park and traveled the country inspecting prisons and schools. The two couples had Sunday dinners together. Their children played together.

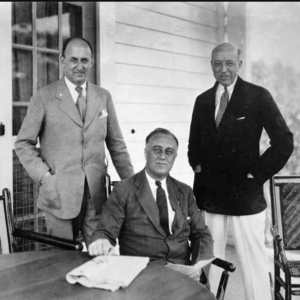

Morganthaw grilled lamb chops at intimate Roosevelt family picnics. This wasn’t just political alliance. This was family. Roosevelt once inscribed a photograph to Eleanor Morganthaw from one of two of a kind. When FDR needed someone to handle sensitive negotiations like the off therecord talks that led to US recognition of the Soviet Union, he sent Morganthaw to bypass the State Department.

When Roosevelt needed emotional support, he called Morganthaw. Eleanor Roosevelt called Morganthaw Franklin’s conscience. For 30 years, that relationship was the foundation of Morganthaw’s identity. In 1933, Roosevelt became president and made Morganthaw head of the Farm Credit Administration. One year later, FDR appointed him secretary of the Treasury, even though Morganthaw had no banking experience and minimal economic training.

Critics said Roosevelt had just handed control of the American economy to an amateur with a farming background. Roosevelt didn’t care. He trusted Morgan Thaw’s judgment more than any economist’s expertise. They had a standing lunch date every Monday, a privilege no other cabinet member enjoyed. For 11 years, Henry Morganthaw managed America’s finances through the Great Depression and World War II.

He helped design the New Deal. He created an elaborate war bond program that raised $49 billion to finance the war. He chaired the Breton Woods conference in 1944 which established the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. By 1945, Morganthaw had served as Treasury Secretary longer than anyone except Albert Galatin in the 1800s.

He believed his mission was to reshape the global economy after the war. He was about to discover that mission died with Franklin Roosevelt. Harry Truman was everything Henry Morganthaw wasn’t. the son of Missouri farmers, not New York real estate magnets, a failed habeddasher who had declared bankruptcy in the 1920s.

A county judge who worked his way through machine politics. Truman had never attended college. He read history books at night and taught himself foreign policy. When Roosevelt picked him as vice president in 1944, it was a political compromise with party bosses, not a partnership based on friendship or respect. Roosevelt barely spoke to Truman during their 82 days together as president and vice president.

FDR didn’t tell Truman about the atomic bomb. He didn’t brief him on the Yalttab agreements with Stalin. He didn’t include him in cabinet meetings. When Roosevelt died on April 12th, 1945, Truman inherited a government he didn’t understand, a war he hadn’t been briefed on, and advisers who viewed him as a temporary placeholder.

Henry Morganthaw looked at Truman and saw an inferior substitute for his best friend. On April 13th, the day after Roosevelt’s funeral, Truman called all of Roosevelt’s cabinet members to the White House. He asked them to stay and help with the transition. Morganthaw agreed immediately. But Truman noticed something in Morganthaw’s demeanor.

Not loyalty, not respect, grief mixed with barely concealed contempt. Morganthal looked at Truman like he was occupying Roosevelt’s chair temporarily, like this was a mistake that history would somehow correct. For the first 6 weeks, the arrangement held together. Morganthaw continued running the Treasury Department.

Truman focused on ending the war in Europe and preparing for the invasion of Japan. They stayed out of each other’s way. But then Truman started making his own policy decisions, decisions that contradicted Roosevelt’s plans. and Morganthaw discovered he couldn’t take orders from someone he considered inferior to his dead friend. The first crack appeared in May 1945.

Truman wanted to reduce wartime tax rates to ease the transition to a peaceime economy. Morganthaw opposed the cuts. He believed they would cause inflation and wreck the federal budget. In previous years, Morganthaw would have argued his position privately with Roosevelt and accepted the final decision.

But this president wasn’t Roosevelt. So Morganthaw did something he had never done in 11 years. He leaked his opposition to the New York Times. The newspaper ran a story. Treasury Secretary opposes Truman tax plan. Truman read the article over breakfast and called Morganthaw to the Oval Office within the hour. He asked Morganthaw directly if he had authorized the leak.

Morganthaw admitted it without apology. He said he had a duty to protect sound economic policy even when the president was wrong. Truman’s response was ice cold. Your duty is to the sitting president, not to Roosevelt’s memory. Morganthaw left that meeting knowing he had crossed a line. But in his mind, he was protecting Roosevelt’s legacy from an incompetent successor.

Matthew Connelly was watching all of this with alarm. Connelly was Truman’s appointment secretary, the gatekeeper who controlled access to the president. He believed loyalty to the sitting president was absolute. When he saw Morganthaw undermining Truman, he started documenting every incident. The Treasury Department meetings Morganthaw held with congressmen without presidential approval.

The policy memos that still referenced Roosevelt’s wishes in present tense. The times Morganthaw told other cabinet members the president wanted something, clearly meaning Roosevelt, not Truman. Connelly took his file to Truman and demanded action. Truman looked at the evidence and said something Connelly would never forget. Connelly, if I fire him now, every newspaper will say I’m purging Roosevelt’s legacy out of jealousy.

I need Morganthaw to fire himself. Connelly tried to argue that Morganthaw was already undermining the presidency with every act of defiance. Truman cut him off. When I move against him, it needs to be so justified that nobody can defend him. Now get out and let me work. That conversation marked the beginning of Truman’s strategy.

He would give Morganthaw enough rope to hang himself. Here’s what Connelly didn’t understand yet. Morganthaw had developed a plan for post-war Germany that Roosevelt had tentatively supported. The Morganthaw plan called for destroying Germany’s industrial capacity and turning it into an agricultural economy.

The goal was to prevent Germany from ever waging war again. strip the factories, dismantle the coal mines, turn 80 million Germans into farmers. It was economic vengeance disguised as peacekeeping. Truman thought the Morganthaw plan was insane. Destroying German industry would European recovery, create mass starvation, and push desperate Germans towards Soviet communism.

But Morganthaw believed Roosevelt had promised to implement this plan after the war. He saw it as Roosevelt’s dying wish and he was determined to force Truman to honor it at the upcoming Potsdam conference in July 1945. In June 1945, Morganthaw began lobbying Truman relentlessly for a seat at Pottsdam.

He argued that he had attended Yaltta with Roosevelt. He insisted his economic expertise was irreplaceable for postwar planning. He reminded Truman that he had chaired the Breton Woods conference. Every argument was really saying the same thing. Roosevelt would have taken me. You should too. Truman listened to all of this with growing irritation.

On June 20th, Truman told Morgan thou he could attend Potsdam, but only as an observer. No policymaking role, no seat at the negotiating table, just a chair against the wall. Morgan thou accepted the humiliation because he thought he could still influence outcomes from the sidelines. But then Truman did something that made Morgan thou realize his influence was over.

Truman appointed Fred Vincent, a Kentucky congressman with no connection to Roosevelt as his chief economic adviser for Potam. Vincent was everything Morganthau wasn’t. A Truman loyalist, a practical politician instead of an idealistic reformer, and most importantly, someone who owed nothing to Roosevelt’s memory. Truman was sending a message that Morganthau couldn’t ignore.

The Roosevelt era was over. The Truman era had begun and Henry Morganthou was being left behind. On July 3rd, Morgan thou submitted a formal written request to be included in the official American delegation to Potam. Truman denied it. Morganthau tried going through Secretary of State James Burns.

Burns told him bluntly, “The president doesn’t want you there. Take the hint.” Think about the devastation of that moment. For 11 years, Morgan thou had been at the center of American economic policy. Now, he was being told to stay home while his replacement attended the most important conference since Yaltta.

Morgan thou had two choices. accept the new reality and resign with dignity or threaten Truman and force a public showdown. On July 5th, 1945, Morganthau walked into the Oval Office and chose confrontation. He told Truman that his participation at Potdam was essential. If Truman excluded him, Morgan thou would resign immediately. It was a calculated threat.

Morgantha believed Truman couldn’t afford to lose Roosevelt’s closest adviser 3 months into his presidency. Truman looked at Morgan thou for a long moment. Then he picked up his pen and wrote on White House stationary, “Your resignation is accepted, effective immediately.” He handed it to his press secretary and said, “Release this within the hour.” Morgan thou was stunned.

He had expected negotiation, a compromise, some acknowledgment of his 11 years of service. Instead, Truman had called his bluff in under 30 seconds. Morgan ththou tried to backtrack. He said he hadn’t meant it as a threat. He explained that he only wanted to serve the country at this critical moment.

Truman cut him off. Henry, I’ve accepted your resignation. Start packing your office. The meeting was over. Morgan ththou left the Oval Office in shock. By the time he reached his car, news reporters were already calling the Treasury Department asking for comment. Truman had ended an 11-year cabinet career before Morgantha could even process what had happened.

Truman didn’t attend Morgan thou’s farewell ceremony at the Treasury Department. He sent a brief letter thanking Morgantha for his service. The letter was three sentences long. Compare that to Roosevelt’s correspondence. Hundreds of personal notes over 30 years. Morgan thou received Truman’s letter at home.

He read it once and threw it in the trash. As far as Morganthau was concerned, Truman had just erased three decades of friendship and service with bureaucratic dismissal. But what neither Truman nor Morgan ththou understood yet was that this firing would reshape American foreign policy for the next 40 years. Because Morgan thou’s departure didn’t just end a personal relationship, it killed the Morganthou plan and everything Roosevelt had envisioned for postwar Germany.

July 23rd, 1945, Fred Vincent stood in the Treasury Department taking the oath of office as the new secretary. These weren’t Roosevelt’s New Deal reformers watching him. These were Truman loyalists who had never worked in the Treasury Department before. Truman moved fast. Just 18 days after accepting Morganthaw’s resignation, he had completely replaced Roosevelt’s economic team. 18 days.

Morgan thou spent 11 years building the wartime economy and Truman replaced him in less than three weeks. Truman’s message was unmistakable. He didn’t care about Roosevelt’s legacy. He didn’t care about continuity. He needed advisers who were loyal to him, not to a dead president’s memory.

And Fred Vincent was about to prove that Truman’s judgment was better than Morgan thou’s threats. Vincent looked at the Treasury Department and saw an agency paralyzed by nostalgia. Career bureaucrats still kept Roosevelt’s portraits on their walls. Policy memos still referenced New Deal principles from 1933. Nobody had accepted that Roosevelt was gone.

Vincent’s first directive was simple. Remove every Roosevelt portrait except the official one in the main hall. update every policy document to reflect current presidential priorities. Stop governing like it was still 1944. He immediately reversed Morganthaw’s approach to postwar Germany. While Morganthau had pushed for industrial destruction, Vincent argued for reconstruction.

Germany needed to rebuild its economy to prevent mass starvation and communist revolution. The Morganthou plan was quietly shelved. By 1947, it would be formally replaced with the Marshall Plan, named after Secretary of State Marshall, which called for massive American investment in European recovery.

Every policy reversal was a silent rebuke to Morganthau. Every dollar invested in German reconstruction proved that Morganthaw’s vengeance-based economics had been wrong. Vincent was building an economic framework that would create NATO, contain Soviet expansion, and win the Cold War. And he was doing it by systematically dismantling everything Morganthau had fought for.

At Potdam in late July 1945, Truman met with Stalin and Churchill without Morganthou anywhere near the negotiations. Truman rejected the Morganthou plan’s harsh terms. He committed America to German reconstruction. He laid the groundwork for what would become the Marshall Plan. Stalin was stunned. He had expected Roosevelt’s policy of Soviet American cooperation to continue.

Instead, Truman was drawing lines that would eventually become the Iron Curtain. The Bretonwood system that Morganthau had designed survived. The International Monetary Fund and World Bank continued, but the harsh post-war punishment Morgan thou had envisioned for Germany died at Potdam. American foreign policy shifted from Roosevelt’s idealistic cooperation with Stalin to Truman’s hard containment doctrine.

And it all happened because Truman had been willing to fire Roosevelt’s closest friend without hesitation. Here’s what Morgan thou never understood. His loyalty to Roosevelt’s memory wasn’t an asset. It was a liability. Truman needed advisers who could adapt to a changing world, not bureaucrats who wanted to implement a dead president’s wishes like religious scripture. Think about that irony.

The man who had helped finance World War II couldn’t see that the post-war world required different thinking than Roosevelt’s 1944 vision. By 1947, the Morganthou plan was completely dead. JCS 1067, the occupation directive that Morgan thou had influenced, was replaced by JCS 1779, which called for German economic growth.

The Marshall Plan pumped billions of dollars into European reconstruction. West Germany became an economic miracle. Truman’s rejection of Morganthaw’s approach had just saved Western Europe from Soviet domination. Truman never apologized for firing Morganthou. Years later, Truman told Associates that Morgan ththou had been a blockhead and a nut who didn’t know from apple butter.

He said Morgan thou had tried to blackmail him with threats of resignation and had gotten exactly what he deserved. But Truman never said these things publicly. They stayed in private conversations and personal papers until historians uncovered them decades later. Henry Morganthaw never admitted Truman had been right.

He spent the rest of his life believing that Roosevelt’s post-war vision would have been superior to Truman’s Cold War containment. But even Morgan thou’s defenders had to acknowledge the results. The Marshall Plan rebuilt Europe. NATO contained Soviet expansion. The Bretton Woods system created decades of economic stability.

Every success proved that Truman had been right to fire the man who couldn’t let go of Roosevelt’s ghost. Historians consistently rate Truman’s decision to fire Morganthau as one of the most important personnel moves of his presidency. It established Truman’s independence from Roosevelt’s shadow. It enabled the policy flexibility that won the Cold War.

It proved that loyalty to the past is worthless when the world demands new thinking. The cabinet secretary, who had served for 11 years, had just been replaced by a man who understood that 11 years of experience means nothing if you can’t adapt. Morganthaw died in 1967 believing until the end that Truman had betrayed Roosevelt’s legacy.

But in his final years, even Morganthaw had to acknowledge what the Marshall Plan had accomplished. When reporters asked him about the post-war reconstruction of Germany, Morganthaw said only, “History decided differently than Roosevelt wished. Whether that was right or wrong, I cannot say. It was the closest he ever came to admitting Truman had been correct.

Truman’s judgment had been vindicated. The Treasury Secretary, who had threatened to resign if he didn’t get his way, discovered that presidents don’t respond well to ultimatums. Morganthaw had believed his 30-year friendship with Roosevelt made him irreplaceable. Truman proved that no one is irreplaceable, not even Roosevelt’s best friend.

Fred Vincent served as Treasury Secretary until 1946 when Truman appointed him Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Before leaving, Vincent told Truman privately, “You were right to fire Morgan thou when you did. If you’d waited even a month longer, he would have poisoned your entire economic policy.” That conversation never made it into official histories.

It stayed buried in Truman’s private papers until long after both men were dead. Henry Morganthaw Jr. retired from public life in 1945. He never held another government position. He never wrote a memoir defending his decisions. When his son Robert asked him years later why he had threatened Truman, Morgan Thaw said only, “I thought loyalty to Franklin mattered more than loyalty to his successor. I was wrong about that.

That admission is recorded in family papers. It never appeared in any published history during Morganthaw’s lifetime. Truman had said Morganthaw was living in the past. He was right. But what Truman understood and what Morganthaw never accepted was that governing requires looking forward, not backward.

The most dangerous cabinet secretaries are the ones who can’t distinguish between honoring a legacy and being imprisoned by it. Truman couldn’t control Roosevelt’s closest friend, but in the end, he didn’t need to.

News

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word Dean Martin had…

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later Hong Kong,…

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory In 1943, the Chinese economy…

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene The coffee cup was…

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING June 18th, 1957,…

A Rival Spy Used a Wiretap on Gambino — He Found His Own Car Filled to the Roof With Expanding Foam

A Rival Spy Used a Wiretap on Gambino — He Found His Own Car Filled to the Roof With Expanding…

End of content

No more pages to load