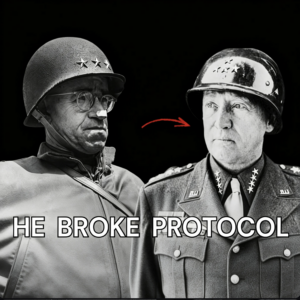

What Bradley Said When Patton Refused To Wake Him Before The Rhine Jump?

March 22nd, 1945, 10:30 in the evening, a headquarters tent somewhere in Germany, 15 miles west of the Rine. General Omar Bradley, commander of the entire American 12th Army Group, responsible for over a million men, sat reading reconnaissance reports when his chief of staff entered carrying a message that had arrived 30 minutes earlier. Bradley read it twice.

Then he sat it down, removed his glasses, and said seven words that never made it into the official war diary. Seven words that revealed more about command, ego, and the strange brotherhood of generals than a thousand pages of military history. Because the message wasn’t a request for orders. It wasn’t a tactical update.

It was a notification, past tense, informing Bradley that one of his army commanders, George Patton, naturally had already done something extraordinary, something dangerous, something that violated the operational plan they’d agreed on just 48 hours earlier. Patton’s third army had crossed the Rine, not next week as scheduled, not with the massive airborne assault and artillery preparation Montgomery was orchestrating 200 m north.

Patton had crossed the previous night in darkness with assault boats and zero fanfare, and he’d waited almost 24 hours before bothering to mention it. The message was vintage patent, three sentences, matterof fact, almost apologetic in its brevity, which somehow made it more insulting, because embedded in those three sentences was a calculated provocation, a deliberate slight, and a question that went unasked, but hung in the air like cordite.

What are you going to do about it, Brad? Bradley’s response wasn’t anger. It wasn’t surprise. It was something more complicated, something that exposed the razor thin line between command authority and personal rivalry in a war where egos were as volatile as ammunition dumps. Because what Bradley said in that moment, and more importantly, what he didn’t say would determine whether Patton’s unauthorized crossing became a triumph or a court marshal offense.

But here’s what makes this moment genuinely fascinating. Here’s why it matters beyond military procedure or command protocol. Because this wasn’t just about two generals. This was about two fundamentally opposed philosophies of warfare colliding at the exact moment when the war was nearly won. When the stakes should have been lowest, when cooperation should have been easiest.

Instead, it became personal. So what exactly did Patton do that night? Why cross the Rine without authorization, without air support, without even waking his commanding officer? And what did Bradley actually say when he found out? Not the sanitized version that appeared in memoirs, but the words his staff heard in that tent before the official record was written, because the truth is messier than the legend and far more interesting.

The race no one admitted was happening. To understand why Patton’s ride crossing mattered, you need to understand what the rine meant in March 1945. Not just a river, a psychological barrier, the last natural defensive line protecting Germany’s industrial heartland. In German military mythology, the Rine was sacred, the border the legions of Rome never permanently breached.

Hitler had staked his final defensive strategy on holding it. Once the Allies crossed the Rine in force, the war was effectively over. Everyone knew it, which meant everyone wanted to be first. Montgomery had been planning his Rine crossing, Operation Plunder, since February. It was massive. Two armies supported by airborne drops, thousands of artillery pieces, elaborate smoke screens, and enough logistical preparation to invade a continent.

The date was set for March 23rd. Churchill was coming to watch. The press was invited. It was going to be the triumph Montgomery believed he’d earned after being denied the single thrust into Germany he’d begged for since Normandy. Patton despised it. Not the operation itself, but what it represented. The cautious, methodical, overwhelming force approach that contradicted everything Patton believed about mobile warfare.

He’d been racing across France and Germany for 9 months, moving faster than supply lines could follow, proving that audacity mattered more than preparation. And now, 15 miles from the Rine, he was being told to wait, to let Montgomery have his moment, to play supporting role in someone else’s theatrical production.

So, Patton decided to cross first, not as part of the plan, as a rejection of it. The opportunity came at Oppenheim, a small town south of Mines. Third Army intelligence had identified weak German defenses there. Under strength units, minimal fortifications, no significant armor.

On the night of March 22nd, while Montgomery’s artillery was still moving into position 200 m north, Patton’s fifth infantry division began fing across the Rine in assault boats. No preliminary bombardment, no air support, just infantry, darkness, and speed. By dawn, they had a full division on theeastern bank. By noon, engineers were constructing pontoon bridges.

By evening, tanks were rolling across. The Germans barely reacted. They’d been expecting the American assault to come farther north, coordinated with Montgomery’s offensive. Patton’s crossing caught them looking the wrong direction. and Patton didn’t tell Bradley any of it until it was irreversible. The message that reached Bradley’s headquarters at 10:30 p.m.

on March 23rd was reportedly brief, have crossed the Rine, opposition negligible, and pushing forward with all possible speed. Some accounts say Patton added a personal postcript. Didn’t want to wake you in the middle of the night. Trust you slept well. That last line, whether Patton actually wrote it or whether it was embellished later, captures the essential cruelty of the gesture.

Because Patton knew exactly what he was doing. He was demonstrating that he could achieve in one night with one division and no fanfare what Montgomery needed two weeks and two armies to accomplish. He was proving Bradley’s caution unnecessary. and he was doing it in a way that left Bradley no choice but to support him publicly while fuming privately. But here’s the complication.

Here’s what makes Bradley’s response so difficult to parse. Because by the time that message arrived, Bradley already knew, not officially, not through command channels, but through the informal network every army develops. staff officers talking to staff officers, liaison teams sharing cigarettes and gossip.

Bradley had heard rumors of the crossing hours earlier, which meant his response wasn’t surprise. It was theater, a performance for the staff officers watching to see how their commanding general would handle insubordination from a man he technically outranked but couldn’t effectively control. What Bradley actually said, “The official record is useless.

” Bradley’s memoirs, published in 1951, describe his reaction as pleased and proud. He claimed he’d always intended for Third Army to cross when opportunity presented itself. He said Patton’s initiative exemplified American tactical flexibility. Pure revision, political necessity after both men had become public figures whose reputations required careful management.

The contemporaneous accounts are more revealing. According to Major Chester Hansen, Bradley’s aid, whose diary entries were declassified in the 1990s, Bradley’s initial reaction was silence. He read Patton’s message twice, set it down, and stared at the map on the table for approximately 30 seconds.

Then he said, “Well, George has always had a nose for publicity.” Not praise, not anger, something colder. Acknowledgment that this wasn’t about military necessity. It was about Patton’s ego, about ensuring his name would be in the newspapers alongside Montgomery’s, preferably above it, about winning a race that existed only in Patton’s mind, but that Bradley was now forced to acknowledge.

Hansen records that Bradley then asked his chief of staff a single question. How long before Sha hears about this? Because that was the real issue. Not whether the crossing was tactically sound. It clearly was. Not whether Patton had the authority. The operational orders gave army commanders discretion to exploit opportunities. But whether Patton’s showboating would create political problems with Eisenhower, with Montgomery, with the carefully balanced Allied command structure that Bradley spent every day trying to hold together. The chief of

staff estimated 2 hours before Patton’s headquarters issued a press release. Bradley nodded. Then he dictated a message to be sent to Eisenhower’s headquarters. Third Army crossed Ry at Oppenheim last night. Bridge head secure. Recommend immediate exploitation. Notice what’s absent. No criticism of Patton.

No mention that Bradley hadn’t been informed until after the fact. just a bland tactical update that made the crossing sound like it had been coordinated all along. Bradley was protecting Patton, not because he approved, but because public criticism of an army commander would reflect badly on Bradley himself. Better to endorse it retroactively.

Claim credit for enabling it. Let Patton have his moment while quietly ensuring the official record showed proper command oversight. But Hansen’s diary includes one more detail. After dictating the message, Bradley allegedly turned to his staff and said, “George just won himself a paragraph in the history books.

Let’s make sure it’s not the last paragraph of his career, a threat wrapped in admiration, a reminder that Bradley still outranked him, and a preview of what would come later. because this wasn’t the last time Patton’s impulsiveness would force Bradley into impossible positions. The call that changed everything. The strangest part of the entire episode happened the next morning, March 23rd, just before noon.

Patton telephoned Bradley’s headquarters personally, not a message through staff officers, not a formal report, a direct call, which wasunusual enough that Bradley’s communications team logged it specially. According to multiple witnesses, Patton was in rare form, jubilant, almost giddy. He described the crossing in theatrical detail, how quiet the night was, how surprised the Germans were, how his engineers had pontoon bridges operational in record time.

He talked about casualties, 28 men in the initial assault wave. By contrast, Montgomery’s operation, which had kicked off that morning, would eventually cost several thousand. Then Patton said something that Hansen recorded phonetically because of how oddly it was phrased. I imagine you’re getting calls from everyone who wishes they’d thought of it first.

Not congratulations, not acknowledgement of Bradley’s authority. A reminder that Patton had outmaneuvered everyone, his rivals, his superiors, maybe even Bradley himself. Hansen’s response, according to Hansen, was deliberate. George, I’m sending you two more divisions. Don’t waste them on publicity stunts. which sounds like support, reinforcements, tactical approval.

But listen to the second sentence. Don’t waste them on publicity stunts. A clear statement that Bradley understood exactly what Patton had done and why. Not a reprimand, too public, too risky, but a boundary, a line drawn. Patton apparently laughed and said something about having plenty of real targets left.

The call ended amicably, but the subtext was clear to everyone listening. Bradley had just reminded Patent that command authority still existed, even if it hadn’t been exercised. Yet, here’s the genuinely fascinating aspect. Within hours, Bradley began receiving congratulatory messages from Eisenhower, from Marshall in Washington, from core commanders throughout 12th Army Group.

Everyone praised his bold decision to authorize Patton’s crossing, his tactical flexibility, his willingness to exploit enemy weakness ahead of schedule. Bradley didn’t correct them. He accepted the credit. And in doing so, he transformed Patton’s insubordination into a command decision retroactively, which was either strategic brilliance or an admission that controlling Patent was impossible.

So, you might as well pretend you’d intended whatever he did all along. The truth? Probably both. The Ryan Crossing made Patton famous. The newspapers loved it. While Montgomery was staging his elaborate setpiece battle, the cowboy general had snuck across in the night and beaten everyone to the punch. It confirmed everything the American public wanted to believe about their military.

That individual initiative mattered more than bureaucratic planning. That audacity trumped caution. that one bold general could change the course of history. Bradley got a footnote, the commanding officer who’d authorized the crossing, whose 12th Army Group had executed the operation. Proper, professional, forgettable.

And that perhaps is what Bradley said that really mattered. Not the words his staff heard in the tent that night, not the veiled threat about history books, but what he said through his actions. that command isn’t about controlling brilliant subordinates. It’s about harnessing them. That you can win by letting someone else take credit as long as the mission succeeds.

That sometimes the best response to insubordination is to endorse it so thoroughly that it stops being insubordination at all. Patton crossed the rine because he needed to prove something to Montgomery, to the press, to himself. Bradley let him because he understood that Patton’s ego, properly directed, was a weapon, dangerous, unpredictable, but effective.

The relationship never fully recovered. Bradley would later block Patton from higher command, would decline to recommend him for promotions, would write in private correspondence that Patton was brilliant but exhausting, and that managing him was like riding a rocket you couldn’t steer. But he never publicly criticized the Ryan crossing, never suggested it was anything other than tactical genius properly supervised because that’s what command required.

And Bradley, for all his blandness, understood command in ways Patton never did. The war ended 6 weeks later. Patton died in a car accident 8 months after that. Bradley lived another 36 years, wrote his memoirs, served as chairman of the joint chiefs, and never once told the full story of what he said that night when Patton refused to wake him.

Maybe because the story wasn’t about what he said. It was about what he didn’t do, didn’t reprimand, didn’t block, didn’t turn into a command crisis that would have distracted from winning the war. Sometimes the most important command decisions are the ones you don’t make. Here at Undiscovered WW2, we uncover the moments that reveal how wars are really fought.

Not on battlefields, but in headquarters tents, through telephone calls, in the space between ego and duty. Subscribe to explore the stories behind the battles you thought you knew.

News

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word Dean Martin had…

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later Hong Kong,…

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory In 1943, the Chinese economy…

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office July 5th, 1945. Harry…

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene The coffee cup was…

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING June 18th, 1957,…

End of content

No more pages to load