When a Protester ATTACKED John Wayne in 1968—His Response Changed Everything

May 18th, 1968. The year America tore itself apart. Sirens wail through New York streets like wounded animals. Protest signs wave above angry crowds like battle flags. The air thick with tear gas and revolution. This is the night John Wayne discovered that true strength isn’t about fighting back.

It’s about rising above. Before we continue, if you haven’t already, hit that subscribe button. You don’t want to miss the stories that reveal who the Duke really was when hatred tried to break him. Madison Square Garden, 7:30 p.m. Outside, chaos reigns. Anti-war protesters line the sidewalks, their voices raw from hours of chanting, “Hell no, we won’t go.

” Echoes off concrete and glass. Police barriers strain under pressure from crowds that surge like ocean waves. Flash bulbs pop like artillery. Reporters shout questions that get lost in the den. Inside the venue, Hollywood’s elite gather for the USO benefit gala, a fundraising event for troops overseas. Stars in tuxedos and evening gowns, smiling for cameras, while outside their fellow Americans scream for blood.

The contrast couldn’t be starker. Inside, champagne and charity. Outside, rage and revolution. The black Lincoln Continental pulls up to the curb with precise timing. Police escort surrounds it immediately. Through bulletproof glass, John Wayne surveys the scene. At 61, he’s fought lung cancer and won lost 30 lb, gained harder edges. The disease didn’t kill him.

It forged him into something more concentrated, more essential. His driver, Pete Martinez, a Marine veteran of Korea, checks the crowd nervously. Duke, it’s rough out there tonight. Maybe we should use the back entrance. Wayne adjusts his black tie with steady fingers. Son, I didn’t spend 40 years in this business to start sneaking through back doors because some kids are upset.

The car door opens. Wayne emerges like a monument coming to life. 6’4 of American granite. His tuxedo is impeccable, tailored on savile row, studs gleaming, shoes polished to mirror brightness. But it’s not the clothes that command attention. It’s the presence. The unmistakable aura of a man who has never backed down from anything.

His shadow falls across the sidewalk like an eclipse. Even the angry protesters pause. This isn’t just another Hollywood celebrity. This is John Wayne, the Duke, the man who won World War II in a 100 movies. The face of American masculinity. The symbol of everything they’re protesting against. The crowd’s energy shifts. Focused, predatory.

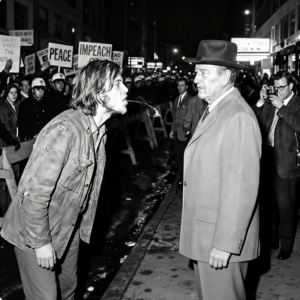

They smell blood in the water. Here’s their chance to strike at the heart of American imperialism. To spit in the face of the military-industrial complex, to make a statement that will echo across every newspaper and television screen in the country. A young man breaks from the crowd, maybe 22 years old, college age, long hair, scraggly beard, wire rimmed glasses.

He wears army surplus fatigues, not because he served, but because he despises those who did. His eyes burn with the righteous fury of someone who has never been tested by anything more challenging than a sociology exam. His name is David Coleman, Columbia University, class of 69. Philosophy major, trust fund baby playing revolutionary.

His father owns textile mills in North Carolina. His mother serves on charity boards in Manhattan. He’s never worked a day in his life, never missed a meal, never faced genuine hardship, but he’s read marks in Chsky and believes he understands the world’s suffering. Coleman pushes through the police line with surprising ease.

The cops are overwhelmed, distracted by the larger crowd. He slips between barriers like smoke. His heart pounds with adrenaline and self-righteousness. This is his moment, his chance to make history, to stand up to the face of American fascism. Wayne’s bodyguards move to intercept, but the kid is fast. Desperate, he ducks under reaching arms, stumbles forward, recovers.

Suddenly, he’s standing directly in front of John Wayne. 3 ft of space between them. The most dangerous 3 ft in America. Time crystallizes. Camera shutters freeze. Voices die. Even the sirens seem to pause. In this moment, two Americas face each other. Old versus young. Tradition versus rebellion. Honor versus rage. Coleman looks up into Wayne’s face and sees everything he hates about his country.

The stern jaw, the level gaze, the unshakable confidence of a man who has never questioned American righteousness. In Wayne’s eyes, Coleman sees John Wayne movies, Warbond drives, patriotic speeches, blind obedience to authority. What Wayne sees is harder to read. Perhaps he recognizes something familiar. The passionate intensity of youth, the desire to matter, to make a difference, to stand for something important.

Perhaps he sees his own son, Michael, who at 26 questions the war his father supports. Perhaps he sees America itself. Wounded, confused, lashing out at its own reflection. Coleman draws back his head, gathers saliva in his mouth, takes careful aim, and spitsdirectly onto John Wayne’s right boot. The Italian leather shoe handmade by craftsmen in Florence, absorbs the insult, a glob of human contempt on polished perfection.

The physical act is minor, just moisture on leather. The symbolic weight is enormous. A young American has just spat on John Wayne, on America itself. Silence explodes across Madison Square Garden Plaza. Not quiet silence, the kind that follows lightning before thunder. Even the wind stops moving. Pigeons freeze on ledges. Traffic lights seem to pause between colors.

Wayne’s bodyguards surge forward. Pete Martinez reaches for his sidearm. Police officers unslling batons. The crowd holds its breath, waiting for the inevitable explosion of violence. This is 1968. This is how these confrontations end with blood on concrete and headlines about American chaos. But Wayne raises his right hand. One gesture, palm out, universal symbol for stop.

His security detail freezes instantly. His fingers don’t tremble. His voice doesn’t crack. He speaks one word. Wait. The authority in that single syllable could stop hurricanes. It carries the weight of 30 years commanding movie sets, handling crises, making decisions under pressure. It contains every western hero he’s ever played.

Every speech he’s ever given, every moment he’s represented American strength. Coleman stands frozen, his own saliva still wet on Wayne’s boot. He expected fury, expected violence, expected to be crushed by American brutality. Instead, he faces something far more unsettling. composure, control, the kind of strength that doesn’t need to prove itself with fists.

Wayne reaches slowly into his jacket pocket. His movements are deliberate, non-threatening, almost ceremonial. What emerges is a white cotton handkerchief, pristine, perfectly folded, monogrammed with his initials in navy blue thread. It’s the kind of old-fashioned accessory that real gentlemen carry that his generation understood as essential equipment.

Without breaking eye contact with Coleman, Wayne kneels down. The action takes 15 seconds that feel like 15 hours. His knees, damaged by decades of horseback riding and stunt work, protests silently. His tuxedo stretches across shoulders that have carried America’s dreams for two generations. He places the handkerchief on his boot and begins to clean slowly, methodically with the same attention to detail he brings to everything in his life.

He doesn’t hurry, doesn’t show anger, doesn’t acknowledge the humiliation. He simply removes the spit from his shoe with the dignity of a king cleaning his crown. The crowd watches in stunned fascination. This isn’t how these stories are supposed to go. The script calls for Wayne to knock Coleman unconscious, to deliver a patriotic speech about respect and authority, to demonstrate American power through American violence.

Instead, he demonstrates something far more powerful. Self-control, grace under pressure, the kind of strength that comes from absolute security in one’s own worth. Wayne finishes cleaning his boot and slowly rises. His knees crack audibly in the silence. He’s getting old. The cancer took something out of him.

But what remains is concentrated essence. Pure John Wayne, distilled to its most potent form. He looks directly into Coleman’s eyes. The young man finds himself trapped in that gaze, unable to look away. Wayne’s eyes are blue gray, the color of storm clouds over the Pacific. They’ve seen everything.

War zones, hospital rooms, the best and worst of human nature. They judge without condemning. They understand without excusing. Wayne extends his right hand toward Coleman, not to strike, not to grab, to offer. In his palm lies the handkerchief, now stained with saliva and shame. When he speaks, his voice carries across the plaza like distant thunder.

Every word carefully chosen. Every syllable waited with meaning. Son, at your age, you should be spilling your blood for this country, not your spit. Take this handkerchief. Keep it. Someday, when you become a real man, you’ll need it to wipe away the sweat of honest work. The words hit Coleman like physical blows, not cruel words.

Not angry words, disappointed words. The kind of disappointment a father shows a son who has failed to live up to his potential. The kind that cuts deeper than any insult because it comes wrapped in sadness rather than fury. Coleman stares at the offered handkerchief. His hands shake. His revolutionary confidence crumbles.

In 30 seconds, John Wayne has accomplished what Columbia University couldn’t manage in 4 years. He’s forced a spoiled child to confront his own emptiness. The handkerchief hangs between them like a bridge between generations. Coleman’s entire worldview depends on Wayne being a monster, a symbol of American brutality that justifies revolutionary violence.

Instead, he’s faced with dignity, with class, with the kind of masculine grace that his generation has rejected but secretly craves. around them. The crowd begins tomurmur, but not with anger, with something approaching awe. They came to witness a confrontation. Instead, they’re seeing a masterclass in character.

They expected John Wayne to validate their worst assumptions about American aggression. Instead, he’s demonstrating American nobility. Coleman’s hand moves toward the handkerchief. Stops. Moves again. His fingers are millimeters from Wayne’s palm when tears begin flowing down his cheeks. Not tears of rage or frustration, tears of recognition, of shame, of understanding that he has just encountered something larger and more powerful than his own small rebellion.

He takes the handkerchief. Wayne nods once. a slight inclination of his head that somehow contains forgiveness, hope, and challenge all at once. He doesn’t smile, doesn’t gloat, doesn’t lecture further. He said what needed saying, done what needed doing. Now it’s time to move forward. He turns toward the Madison Square Garden entrance without looking back.

His stride is unhurried, purposeful. Every step radiates confidence regained behind him. Silence maintains its grip on the plaza. Even the hardest protesters find themselves speechless. Pete Martinez falls into step beside him. Duke, that was I’ve never seen anything like that. Wayne doesn’t respond immediately.

They’re almost to the doors when he speaks. His voice quiet enough that only Martinez can hear. Pete, anger is easy. Any fool can get angry. Dignity is hard. That’s what separates men from boys. Inside Madison Square Garden, the gala continues. Hollywood stars mingle with military brass. Champagne flows. Cameras capture smiles and handshakes.

But the real story is happening outside where a crowd of protesters stands in stunned silence trying to process what they’ve just witnessed. Coleman remains frozen in place. Wayne’s handkerchief clutched in his fist. Around him, his fellow revolutionaries begin to disperse. The energy has gone out of them.

Their target has refused to be a target. Their enemy has revealed himself as something else entirely, a teacher. Over the following weeks, the story spreads through underground networks and mainstream media alike. But it changes with each telling. Some versions have Wayne delivering a patriotic speech. Others have him engaging in a lengthy debate about Vietnam.

Still others claim he struck Coleman down with a single punch. The truth is simpler and more powerful. John Wayne said 16 words and handed over a handkerchief. In doing so, he demonstrated that real strength doesn’t come from the ability to destroy enemies. It comes from the ability to create better men. Coleman keeps the handkerchief for the rest of his life.

He graduates from Colombia, abandons his revolutionary pretensions, becomes a teacher in inner city schools. He never speaks publicly about his encounter with Wayne. But 30 years later, when his own son asks about the faded white cloth in a frame on his father’s desk, Coleman tells the story.

I was young and angry and thought I knew everything, he explains. Then I met a man who showed me the difference between being strong and being good. Between making noise and making a difference. That handkerchief reminds me that real courage isn’t about fighting. It’s about choosing not to fight when fighting would be easy. The encounter becomes a legend within Hollywood circles.

Directors and producers learn to recognize the Wayne standard. The idea that true strength reveals itself through restraint. that the most powerful response to hatred is not greater hatred but something approaching love. Years later, when asked about that night outside Madison Square Garden, Wayne would only say, “Sometimes you win more battles by not fighting them. That boy wasn’t my enemy.

He was America’s future. My job wasn’t to defeat him. It was to help him become worthy of that future.” The handkerchief incident becomes a turning point in Wayne’s public image. Critics who once dismissed him as a wararmonger begin to recognize depths they hadn’t noticed. His support for the Vietnam War continues, but it’s tempered now by a visible compassion for those who oppose it.

He begins to understand that patriotism doesn’t require unonymity. It requires dialogue. Coleman’s spit on Wayne’s boot was meant to humiliate. Instead, it revealed something magnificent about American character. Not the America of politicians and protesters, but the America of individuals who choose grace over vengeance, understanding over anger, hope over despair.

That night, outside Madison Square Garden, two Americans met in the space between hatred and healing. One tried to tear down, the other chose to build up. The difference between them wasn’t age or politics or social class. The difference was character. And character, as John Wayne proved that night, is the only thing that can heal a nation at war with itself.

News

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word Dean Martin had…

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later Hong Kong,…

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory In 1943, the Chinese economy…

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office July 5th, 1945. Harry…

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene The coffee cup was…

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING June 18th, 1957,…

End of content

No more pages to load