When Japanese Cut Off This American’s Ear — He Killed All 41 of Them in 36 Minutes

At 4:47 on the morning of May 11th, 1945, Private John McKini lay in his tent near Dingolan Bay, Luzon, unaware that approximately 100 Japanese soldiers were creeping through the jungle toward his position. 24 years old, 2 and 1/2 years in the army, a sharecropper son from Georgia with a third grade education.

By May 1945, the Philippine campaign had already cost the United States over 60,000 casualties. Japanese forces on Luzon refused to surrender. They launched night attacks, dawn raids, suicide charges against American perimeters. Company A of the 123rd Infantry Regiment, 33rd Infantry Division, had established an outpost near Dingolan Bay in Tayabas Province.

The position guarded a crucial supply route. Three Americans manned a light machine gun on the perimeter. McKini had just finished a long shift at that gun. He walked a few paces to his tent, laid down with his M1 rifle beside him. The jungle was quiet. The Japanese knew this outpost existed.

They had been watching it for days, counting the Americans, timing the guard rotations, planning their assault. The attack force moved through the darkness. Over 100 soldiers from remnants of Japanese units still fighting on Luzon. They carried rifles, grenades, knee mortars, and swords. Their objective was simple. Overrun the American position. Kill everyone.

Capture the supplies. The vanguard slipped past the outer guard post undetected. Sergeant Fukutaro Mori led the advance element. His orders were to eliminate the first Americans silently. No gunfire, swords and bayonets only. By the time the main force attacked, the perimeter would already be compromised. Murray reached Mckin’s tent.

He could hear the American breathing inside. One quick strike would end this man’s life before he could raise an alarm. McKini had grown up hunting in the Georgia woods. His father was a sharecropper in Scran County. The family had nothing. Jon learned to shoot before he learned to read.

By the time he was 12, he could hit a squirrel at 50 yards with a 22 rifle. He trapped rabbits, shot deer. Fishing and hunting put food on the family table when the crops failed. He enlisted at Fort McFersonson in November 1942. The army discovered he could barely read or write. They also discovered he was one of the best marksmen they had ever seen.

His qualification scores were exceptional. Drill sergeants noticed he moved through the woods differently than other soldiers. Quieter, more aware. He had spent his entire life in environments where a single mistake meant going hungry. The 33rd Infantry Division shipped to the Pacific in 1943. McKini fought through New Guinea, survived the jungle, survived the Japanese, survived malaria and dysentery and everything else the Pacific theater threw at American soldiers.

By May 1945, he was a veteran, quiet, kept to himself, did his duty, never complained. His fellow soldiers knew two things about John McKini. He was the best shot in the company, and he slept with his rifle. That rifle was about to save his life. If you want to see how McKini survived what happened next, please hit that like button.

It helps us share these forgotten stories with more people. And please subscribe if you haven’t already. Back to McKini. Sergeant my threw open the tent flap at 451. The sword came down in a diagonal slash aimed at McKinn’s neck. In the darkness, my misjudged the distance. The blade caught McKini on the side of the head instead.

It severed part of his right ear. Blood sprayed across the tent canvas. McKinn’s eyes opened to searing pain and the silhouette of a man standing over him with a raised sword. He had less than 1 second to react. My was already bringing the blade down for a second strike. This one would not miss. McKinn’s hand found his rifle in the darkness. He did not aim.

He did not think. 24 years of survival instinct took over. He swung the M1 like a club. The rifle butt caught Mory under the chin with enough force to shatter bone. The Japanese sergeant staggered. McKini swung again. The second blow crushed Mory’s skull. Outside the tent, McKini could hear them. Footsteps. Dozens of footsteps moving fast through the camp.

The main assault had begun. He was bleeding badly from his ear. His head was ringing from the sword strike. And somewhere in the darkness, nearly 100 Japanese soldiers were coming to kill everyone he knew. McKini grabbed his rifle and stepped out of the tent. What he saw made his blood run cold. The machine gun position was 30 yards from his tent.

Three Americans had been manning it when he went to rest. Now he could see muzzle flashes in the darkness, screaming, the distinctive crack of Arisaka rifles mixing with the heavier reports of M1 Garands. Japanese soldiers were pouring through the perimeter from the northeast. They moved in waves. The first wave had already reached the machine gun imp placement.

McKini could see figures struggling in the darkness around the gunpit. His mind processed the tactical situation inseconds. The machine gun was the key to the entire position. It covered the main approach to the American camp. If the Japanese captured it and turned it around, they could rake the entire perimeter with fire.

Every American in Company A would die. McKini ran toward the gun. The two soldiers who had replaced him at the machine gun were fighting for their lives. Private James Hrix had taken a bayonet wound to the shoulder in the first seconds of the attack. The third man, seeing Hendrickx go down, made a decision. He grabbed his wounded comrade and dragged him toward the rear of the perimeter.

It was the right call. Hendrickx would have bled out if left behind. But it meant the machine gun was now undefended. 10 Japanese infantry men reached the imp placement before McKini could get there. They swarmed over the sandbag wall. One of them immediately began trying to turn the gun around. The others provided security, rifles pointed outward, watching for any American counterattack.

McKini did not slow down. He did not take cover. He did not wait for backup. He sprinted directly at 10 enemy soldiers who had just captured the most important weapon in the entire outpost. The Japanese saw him coming. A single American bleeding from a head wound, charging straight at them in the pre-dawn darkness.

Two of them raised their rifles. McKini was faster. He shot the first man at 15 yards. The M1’s report echoed across the camp. He shot the second man at 10 yard. By the time he reached the sandbag wall, he had fired four rounds. Four Japanese soldiers were down. He leaped into the imp placement. The space inside was roughly 8 ft by 6 ft.

Six enemy soldiers were still alive in that confined area. Some were trying to swing their rifles around. Others reached for bayonets. One was still fumbling with the machine guns traversing mechanism. McKini landed among them and kept firing. point blank range. The M1 Garand held eight rounds in its internal magazine.

He had already fired four. He put the next three rounds into three more Japanese soldiers at distances measured in inches rather than yards. One round left. The eighth man was directly in front of him. Bayonet raised for a thrust at McKin’s chest. McKini fired his last round. The soldier dropped.

The M1 Garand’s bolt locked back on an empty magazine with its distinctive metallic ping. Three Japanese soldiers were still alive in the gunpit. They had heard that sound. They knew what it meant. McKini reversed his grip on the rifle before the empty clip had finished ejecting. He swung the weapon like an axe. The walnut stock connected with the first soldier’s temple. The man collapsed.

McKini swung again. The second soldier tried to block with his forearm. The rifle butt shattered bone and continued into his skull. The third soldier lunged with a bayonet. McKini sidestepped and brought the rifle down on the back of the man’s neck. The vertebrae cracked audibly. 10 Japanese soldiers had captured the machine gun.

30 seconds later, all 10 were dead. McKini grabbed for the machine gun. His hands found the receiver. Something was wrong. During the struggle, the weapon had been damaged. The bolt was jammed. The feed tray was bent. He cycled the charging handle twice. Nothing. The gun would not fire. The most important weapon in the perimeter was now useless.

McKini looked up from the broken machine gun. Dawn was starting to lighten the eastern horizon, and in that gray light, he could see them. More Japanese soldiers. Many more. They were regrouping at the edge of the jungle, preparing for the next wave. He had an M1 rifle with an empty magazine. He had just killed 10 men in hand-to-hand combat.

His ear was still bleeding, and the main assault had not even started yet. McKini reached down and pulled a bandelier of ammunition from one of the dead Japanese soldiers. American 30 caliber rounds. The man had probably taken them from a previous engagement. McKenna loaded a fresh clip into his rifle. Somewhere in the darkness, a Japanese officer was shouting orders.

McKenna could not understand the words, but he understood the tone. They were coming again. He settled into the gunpit among the bodies of the men he had just killed, rested his rifle on the sandbag wall, and waited. The second wave emerged from the jungle 60 yard away. McKenna counted at least 20 soldiers in the first line, more behind them.

They came at a run, rifles with fixed bayonets extended, screaming as they charged. McKenna put his front sight on the lead soldier and squeeze the trigger. The M1 Garand was designed for rapid semi-automatic fire. A trained soldier could put eight aimed rounds down range in under 10 seconds. McKenna was not a trained soldier.

He was a hunter from Georgia who had been shooting since childhood. He was faster. The first Japanese soldier dropped at 60 yards. McKenna shifted his aim. The second man fell, then the third. The M1 kicked against his shoulder with each shot.Brass casings ejected to his right. He did not think about what he was doing. His body remembered thousands of hours in the Georgia woods. Lead the target.

Squeeze the trigger. Acquire the next target. Repeat. The clip ejected with a ping. McKini slammed in a fresh one from the bandelier. The charging wave had covered 20 yards during his reload. 40 yards now. He started firing again. The Japanese soldiers in the second wave had expected to find a captured machine gun position.

They had expected their comrades to be turning that gun on the sleeping Americans. Instead, they found one man with a rifle cutting them down with mechanical precision. Eight rounds. Reload. Eight rounds. Reload. Some of the attackers made it to within 15 yards of the gunpit before McKenna dropped them.

Others tried to veer left or right, seeking cover. He tracked them and fired. A soldier who moved was easier to hit than a soldier who stood still. McKenna had learned that hunting deer. The second wave broke. The survivors scattered back toward the jungle. McKini counted the bodies in front of his position. 11 more, 21 total since the attack began.

He did not have time to feel relief. Japanese officers were already reorganizing. He could hear them shouting beyond the treeine. And now he heard something else. A hollow thump from somewhere in the jungle. Then another knee mortars. The first round exploded 10 yards to his left. Dirt and shrapnel sprayed across the gunpit.

McKenna flattened himself against the sandbags. The second round hit closer. The third landed directly on the parapet, showering him with debris. The Japanese had learned from the first two waves they were not going to charge blindly into his rifle fire again. They would soften the position with mortars first, kill him, or force him to keep his head down, then send in the infantry.

McKini understood the tactical problem immediately. If he stayed in the gunpit, the mortars would eventually find him. The Japanese gunners were adjusting their aim with each shot, getting closer. But if he moved, he would lose the only fortified position in this section of the perimeter. A grenade landed 3 ft away from him. McKini grabbed it and threw it back over the sandbags. It exploded in midair.

The blast wave knocked him sideways. His ears were ringing now. Blood from his severed ear had soaked through the makeshift bandage he had pressed against the wound. Another mortar round hit the sandbags directly. The wall partially collapsed. McKini was now half exposed to the jungle. He made his decision. Staying meant death.

He grabbed two bandeliers of ammunition from the dead soldiers around him, slung them over his shoulder, and ran. The Japanese saw him moving. Rifle fire cracked from the treeine. Bullets snapped past his head. McKini sprinted 15 yards to a shallow depression in the ground. Not a proper foxhole, just a slight dip in the terrain.

He threw himself into it and rolled onto his back. Rounds kicked up dirt inches from his face. He crawled to the edge of the depression. Found a firing position. The Japanese infantry was moving again. They thought he was running. They thought he was retreating. Two squads emerged from the jungle at a fast walk, rifles ready, moving toward the abandoned gunpit.

McKini let them get to 30 yards. Then he opened fire. The attackers had bunched together while crossing the open ground. A mistake. McKinn’s first shot dropped the point man. His second hit the soldier directly behind. The group scattered, but there was no cover between the jungle and McKinn’s new position. He picked them off as they ran. Eight rounds. Reload.

The survivors reached the gunpit and found only bodies. Their comrades from the first wave. They had expected to find the American there. Instead, they found him shooting at them from a completely different angle. Three more fell before they could locate his muzzle flash. McKenna changed position again. He moved 10 yards to his right while the Japanese tried to reorganize.

Found another depression, started firing from the new location. He was doing what he had done in the Georgia woods. Never stay in one place. Never let your target predict where the next shot will come from. A deer that hears one gunshot will freeze. A deer that hears two from different locations will run in circles.

The Japanese were running in circles. Dawn light was spreading across the sky. McKini had been fighting for 18 minutes. His ammunition was running low. His ear was still bleeding. And he could see movement in the jungle that suggested the enemy was massing for another major push.

He needed more ammunition, and he knew exactly where to find it. The dead Japanese soldiers around the gunpit carried ammunition. Not just the 30 caliber rounds he had already scavenged. Some of them had Arisaka rifles with full pouches. Others had grenades clipped to their belts. McKini needed to get back there. He waited for a lull in the mortar fire, counted tothree, then sprinted across the open ground toward the gunpit.

Rifle fire erupted from the treeine. McKini ran in a zigzag pattern. A bullet tugged at his sleeve. Another cracked past his ear. He dove the last 5 ft and landed among the bodies he had created 20 minutes earlier. The smell hit him immediately. Blood and cordite and something else. The copper tang of death. McKini ignored it.

He had butchered hogs on the farm, had gutted deer in the Georgia heat. The smell of death was familiar. He moved quickly through the bodies, grabbed every bandelier he could find, every loose clip. He found four American ammunition pouches on men who had probably taken them as trophies. 64 more rounds.

He stuffed the clips into his pockets and belt. A Japanese soldier appeared over the sandbag wall. He must have crawled forward while Mckin was gathering ammunition. The man’s rifle was already coming up. McKini shot him through the chest at 2 feet. He grabbed the dead man’s grenades, three of them. Japanese type 97 fragmentation grenades.

He had never used one before, but he had seen them. Knew how they worked. Pull the pin. Strike the cap against something hard. Count to four. Throw. Movement in his peripheral vision. More soldiers approaching from the left. McKini armed a grenade. counted and threw it over the sandbags. The explosion was followed by screaming.

He armed the second grenade, threw it toward the treeine where muzzle flashes were concentrated. More screaming. He was out of the gunpit before the third grenade left his hand. Running again, a new position. Keep moving. The sky was light enough now to see clearly. McKini found a shell crater 15 yd from his previous depression. dropped into it.

The crater was 3 ft deep, enough cover to protect him from direct fire. He could see the entire approach from the jungle to the perimeter. Bodies littered the ground between his position and the trees. He counted quickly. 28, maybe 30. Some were still moving. Wounded men trying to crawl back toward their lines.

McKini let them go. A wounded man required two healthy soldiers to carry him. Every casualty he created multiplied the enemy’s problems. The mortar fire had stopped. McKini understood why. The Japanese had lost visual contact with him. Their mortar crews could not adjust fire on a target they could not see.

He had 15, maybe 20 minutes before they repositioned observers. He used the time to reload every empty clip he carried. His fingers worked automatically. Press the rounds into the clip. Feel for the spring tension. eight rounds per clip. He had scavenged enough ammunition for approximately 10 reloads. 80 rounds. 80 rounds against however many Japanese soldiers were still in that jungle.

The attack had lasted 23 minutes. McKini had killed or wounded at least 30 enemy soldiers, but he knew the math was not in his favor. The Japanese had started with roughly 100 men. Even if half of them were down, that left 50, and he was still alone. Where was the rest of company A? The answer was complicated. The Japanese attack had hit multiple points along the perimeter simultaneously.

McKin’s position was on the northeast flank. Other soldiers were fighting their own battles on the south and west sides of the camp. The company commander was trying to organize a coherent defense. But in the darkness and chaos of a night attack, coordination was almost impossible. McKini did not know any of this. He knew only that no one had come to help him.

No reinforcements, no supporting fire, just him, his rifle, and the bodies piling up in front of his position. The Japanese regrouped at the edge of the jungle. McKini could see them through the trees, soldiers checking weapons, NCOs’s moving among the ranks, and officers studying the American perimeter through binoculars.

They had expected to overrun this outpost in 5 minutes. They had lost nearly a third of their force to one man in 23 minutes, and they still had not broken through. The officer lowered his binoculars. McKini saw him gesture toward a specific section of the perimeter. Not the gunpit, not the craters where McKini had been fighting.

The officer was pointing at the supply tents. A different approach, a new axis of attack designed to bypass the killing ground McKini had created. McKenna read the enemy’s intention instantly. They were going to swing around his flank, hit the camp from a direction he could not cover, and there was nothing he could do to stop them from his current position. He had a choice.

Stay in his crater where he had cover and clear fields of fire, or move to intercept an attack he might not reach in time. McKini climbed out of the crater and started running toward the supply tents. The supply tents were 40 yards from his crater. McKini covered the distance in 8 seconds.

He threw himself behind a stack of ammunition crates just as the first Japanese soldiers emerged from the jungle on the southern approach. They had not expected him to be there. Thelead element consisted of 12 soldiers moving in a tactical column. They were heading for the gap between two tents. Once through that gap, they would be inside the American perimeter with clear shots at soldiers fighting on other sections of the line.

McKini opened fire from behind the crates. The first three men in the column went down before the others could react. The fourth and fifth tried to return fire, but could not locate him in the shadows between the tents. McKini shot them both. The remaining seven scattered. Some ran back toward the jungle.

Others dove for cover behind fallen logs and shallow depressions. McKini tracked the ones who went to ground. They were pinned, unable to advance, unable to retreat without exposing themselves. He shifted his aim to the treeine. More soldiers were emerging. The Japanese commander had committed his reserve force to this flanking attack. 20 more men, maybe 25.

They saw their comrades pinned down and hesitated at the edge of the jungle. That hesitation cost them. McKini fired into the clustered soldiers. Eight rounds. Reload. Eight rounds. Bodies dropped among the trees. The survivors pulled back into deeper cover. 26 minutes into the attack, McKini had now killed or wounded at least 35 enemy soldiers.

The Japanese had tried three different approaches. Frontal assault on the machine gun. Mortar bombardment followed by infantry. Flanking maneuver toward the supply area. All three had failed. The Japanese commander faced a problem he had never encountered. His intelligence had indicated this outpost was defended by a small American force with limited heavy weapons.

Standard doctrine called for overwhelming night attacks against such positions. Speed and numbers would compensate for any defensive advantages, but one man had disrupted everything. The commander did not know it was one man. His soldiers reported heavy fire from multiple positions. They had seen muzzle flashes from the gunpit, then from a depression 30 yards away, then from behind the supply crates.

It appeared the Americans had established interlocking fields of fire with several riflemen supporting each other. This assessment was wrong, but it shaped Japanese tactics for the next phase of the battle. The mortar crews repositioned to the southwest. They began dropping rounds on the supply area.

McKini heard the first impacts and moved immediately. He had learned static positions attracted mortar fire. Movement meant survival. He ran north along the inside of the perimeter, found a foxhole that had been abandoned when its occupant went to reinforce the southern defense. Dropped into it. The hole was deeper than his previous positions, 4 ft down with a firing step that let him see over the lip.

The Japanese infantry attacked again, this time from two directions simultaneously. One group from the south, another from the original northeastern approach. They were trying to split his fire, force him to choose which attack to engage. McKini engaged both. He fired four rounds at the southern group, dropped two men, swung his rifle northeast, fired four rounds at that group, dropped two more.

The M1 pinged empty. He reloaded in under 3 seconds, fired at the southern group again. The attack stalled. Neither group could advance into the withering rifle fire, but neither group retreated either. They went to ground and started returning fire. Bullets cracked over Mckin’s head.

rounds thudded into the dirt around the foxhole. He was now taking fire from two directions. His ammunition was running low. And the Japanese were learning. They had figured out that the fire was coming from a single location. One rifleman, not a squad, not interlocking positions, just one man who moved fast and shot accurately.

This knowledge changed everything. The Japanese soldiers stopped attacking in waves. They began advancing individually. One man would move while others provided covering fire. Then another man would move, leaprogging forward, closing the distance yard by yard. It was a tactic designed to overwhelm a single defender. Even the best marksmen could not track multiple targets moving at different times from different directions.

Eventually, someone would get close enough. McKini recognized what they were doing. He had hunted animals that used similar tactics. A pack of coyotes would spread out and approach prey from multiple angles. The prey could only watch one threat at a time. The others would close in. He was the prey now. 31 minutes.

The Japanese had closed to within 20 yards on the southern approach, 15 yards on the northeast. McKini had fewer than 30 rounds remaining. The foxhole that had protected him was about to become his grave. McKini did not wait for them to reach him. He burst out of the foxhole and charged directly at the nearest group of Japanese soldiers.

Five men were crouched behind a fallen palm tree 15 yards to the northeast. They had been waiting for their comrades to close fromthe other side. They did not expect their target to attack. McKini shot the first man while still running. Shot the second as he reached the log. The third soldier rose to meet him with a bayonet thrust.

McKini sidestepped and slammed his rifle butt into the man’s face. Bone crunched. The soldier went down. The fourth man swung his rifle like a club. McKini ducked under the blow and drove the steel butt plate of his M1 into the soldier’s throat. The fifth man tried to run. McKini shot him in the back at three yards.

He kept moving, could not stop. Stopping meant death. The southern group had seen him leave the foxhole. They were sprinting toward his position. McKini turned and fired. Two men dropped. The others kept coming. He fired again. Another man fell. The M1 pinged empty. Three Japanese soldiers reached him before he could reload. The first one tackled him around the waist.

McKini went down hard. His rifle flew from his hands. The second soldier stomped on his wounded ear. Pain exploded through his skull. The third raised the bayonet for a killing thrust. McKini grabbed the ankle of the man standing on his head and twisted. The soldier lost his balance and fell. McKini rolled, throwing off the man who had tackled him.

The bayonet thrust missed his chest by inches, and buried itself in the dirt. He scrambled to his knees, found his rifle, swung it in a wide arc that caught one soldier across the temple. The man collapsed. McKini reversed the swing and drove the butt plate into another soldier’s ribs. He felt bones break under the impact.

The third soldier had pulled his bayonet from the ground. He lunged. McKini blocked the thrust with his rifle barrel. The blade slid along the wood and steel, gouging a furrow in the stock. McKini stepped inside the man’s reach and headbutted him. The soldier staggered. McKini hit him twice more with the rifle butt. He stopped moving.

33 minutes since the attack began. McKini was breathing hard. His hands were slick with blood. Some of it was his own. His ear was a mass of torn flesh and dried gore. His uniform was ripped in a dozen places. He had bruises and cuts he did not remember receiving. But he was still alive. He looked around the battlefield. Bodies everywhere.

Japanese soldiers who had come to kill Americans and found something they had not expected. More bodies than he could count in the gray morning light. Movement to his right. Two more soldiers emerging from the jungle. McKini raised his rifle and realized it was empty. He had not reloaded after the hand-to-h hand fighting.

The two soldiers saw him standing among the bodies of their comrades. They hesitated. McKini charged them. He covered 10 yards before they could react. The first soldier tried to bring his rifle up. Too slow. McKinn’s rifle butt caught him under the chin. The second soldier turned to run. McKini chased him down in three strides and clubbed him from behind. 34 minutes.

The mortar position. McKini remembered seeing muzzle flashes from the southwest. The knee mortars had been pounding his positions throughout the battle. Taking out those crews would eliminate the indirect fire threat. He found a loaded rifle among the dead. An M1 with a full clip. Picked it up, dropped his damaged weapon, started moving toward the mortar position.

The mortar crews saw him coming. Two men. They had been adjusting their weapon for another fire mission. Now they scrambled to defend themselves. One reached for a rifle. The other tried to arm a grenade. McKini shot them both from 45 yd. 35 minutes. He stood in the morning light, scanning the jungle for more targets.

His chest heaved. His vision was blurring from exhaustion and blood loss. Every muscle in his body screamed for rest. The jungle was quiet. No more soldiers emerging from the trees. No more mortar rounds. No more rifle fire from concealed positions, just the moans of wounded men and the buzzing of flies already gathering on the dead.

McKini walked back toward the American perimeter. He was halfway there when he saw figures moving toward him. American uniforms, soldiers from company A who had finally fought through to his section of the line. They stopped when they saw him covered in blood, carrying a rifle that was not his own, surrounded by bodies. McKini lowered his weapon.

The reinforcements stared at the carnage around him, at the shattered machine gun position, at the scattered corpses stretching from the jungle to the perimeter. 36 minutes after Sergeant Fukutaro my slashed open his tent, Private John McKini was still standing, still breathing, still in complete control of the area.

The battle was over, but no one yet understood what had actually happened. The soldiers who reached McKenna that morning were from second platoon. They had been fighting on the western edge of the perimeter when the Japanese attack hit. It took them 36 minutes to push through to McKenna’s position. What they found defied comprehension.

Bodies lay scattered across an area roughly 100 yardds long and 60 yards wide. Japanese soldiers slumped over sandbags, crumpled in shell craters, sprawled among the supply crates, piled on top of each other near the damaged machine gun imp placement. The platoon sergeant ordered a count. His men moved through the battlefield, checking bodies, marking positions.

The count took 20 minutes. When they finished, the sergeant did not believe the number. He ordered them to count again. 38 dead Japanese soldiers lay in the immediate vicinity of the machine gun position. Two more bodies were found near the mortar imp placement 45 yd away. 40 confirmed kills in a space that one man had defended for 36 minutes.

The sergeant found McKenna sitting on an ammunition crate. The private was pressing a blood soaked bandage against what remained of his right ear. His uniform was torn and stained. His rifle stock was cracked from repeated impacts against human skulls. He looked like a man who had walked through hell. The sergeant asked what had happened.

McKenna gave a brief account. The tent, the sword, the machine gun, the waves of attackers. He spoke in short sentences. No embellishment, no drama, just facts. The sergeant did not believe him. No single soldier could kill 40 men in 36 minutes. It was impossible. There must have been other defenders.

Other riflemen supporting Mckin’s position. The private was confused from blood loss and combat stress, but the other soldiers in company A had been accounted for. The two men who originally manned the machine gun with McKini had evacuated to the rear with wounds. Everyone else had been fighting on different sections of the perimeter.

The ballistic evidence supported Mckin’s account. Spent M1 casings littered the ground at exactly the positions he described. The trajectory of wounds on the Japanese bodies matched the firing angles from those positions. One man, 40 kills, 36 minutes. Company A’s commanding officer forwarded a report to battalion headquarters.

Battalion forwarded it to regiment. Regiment forwarded it to division. At each level, officers read the account and assumed it was exaggerated. Combat reports often inflated enemy casualties. Soldiers under stress made mistakes. The numbers had to be wrong. The 33rd Infantry Division sent an intelligence team to verify the report.

They interviewed McKini, interviewed witnesses, examined the battlefield, counted the bodies again. Some accounts suggested the actual number of Japanese dead exceeded 100, but only 40 could be directly attributed to McKinn’s actions with certainty. The investigators reached an unavoidable conclusion. The report was accurate.

Private John McKini had single-handedly repelled an attack by approximately 100 Japanese soldiers. He had killed 40 of them. He had saved his company from potential annihilation. The recommendation for the Medal of Honor went forward in June 1945. The Medal of Honor is the highest military decoration awarded by the United States government.

Fewer than 3,500 have been awarded since the Civil War. The criteria are specific. The recipient must have distinguished himself conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. McKin’s actions exceeded those criteria by any reasonable measure. The recommendation moved through channels.

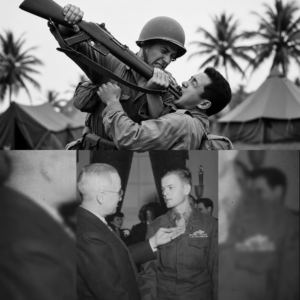

War Department reviewers examined the evidence. They found the same thing the division investigators had found. The story was true. Every detail was supported by witness testimony and physical evidence. On January 23rd, 1946, Private John McKini stood in the White House. President Harry Truman placed a Medal of Honor around his neck.

The citation described his actions in formal military language. Extreme gallantry, unsurpassed intrepidity, single-handedly thwarting an assault that threatened to annihilate his company. McKenna did not give speeches. He did not seek publicity. When reporters asked about the battle, he gave the same brief answers he had given the sergeant that morning on Luzon.

the tent, the sword, the machine gun, the waves of attackers. The press called him the Pacific’s Audi Murphy. Murphy had received his Medal of Honor for single-handedly holding off German forces in France. McKenna had done something similar against Japanese forces in the Philippines. Both men had faced overwhelming odds.

Both had refused to retreat. Both had emerged victorious through a combination of skill, courage, and something that defied easy explanation. But while Murphy became a movie star after the war, McKini went home to Georgia. He was 25 years old. He had a Medal of Honor, a third grade education, and a partially severed ear that would never fully heal.

The war was over. The killing was done. John McKini had to figure out how to be a normal person again. John McKini returned to Scrubbing County, Georgia in 1946. He went back to the only life he knew, farming, hunting,fishing in the same creeks where he had learned to shoot as a boy. He rarely spoke about the war.

Neighbors knew he had received the Medal of Honor. They had seen the newspaper articles, but McKini never brought it up, never displayed the medal, never attended reunions or gave interviews. When people asked about Luzon, he would say a few words and then change the subject. The nightmares were a different matter. His family knew about those.

The sounds he made in his sleep. The way he would wake suddenly, reaching for a rifle that was not there. The war had followed him home in ways that no medal could address. Post-traumatic stress disorder was not a recognized diagnosis. In 1946, soldiers who struggled with combat memories were told to forget about it, move on, be grateful they survived.

McKenna did what most veterans of his generation did. He buried the memories and kept working. He married, raised a family, worked various jobs around Screven County. The years passed. Korea came and went. Vietnam came and went. New wars created new heroes and new veterans with their own buried memories. McKini remained in Georgia, quietly living, quietly aging.

The Medal of Honor sat in a drawer somewhere. He had earned the nation’s highest military decoration, and most of his neighbors had no idea. In 1965, author Forest Bryant Johnson began researching McKenna’s story. Johnson was a veteran himself. He understood what McKini had experienced. He spent years tracking down witnesses, examining military records, and piecing together the details of those 36 minutes on Luzon. The research was difficult.

McKini did not want to talk. Many of the witnesses had died. Military records were scattered across multiple archives, but Johnson persisted. He believed the story deserved to be told. His book, Phantom Warrior, was published in 2007. It documented Mckin’s childhood in Georgia, his service in the Pacific, and the battle that earned him the Medal of Honor.

The book brought renewed attention to a hero most Americans had never heard of. McKini did not live to see the book published. He died on April 5th, 1997 in Sylvania, Georgia. He was 76 years old. The sharecropper’s son, who had killed 40 Japanese soldiers with a rifle and his bare hands, passed away quietly, surrounded by family.

He was buried in Scrubbin County, not far from the land where he had learned to hunt. 20 years after his death, Georgia honored him again. In 2017, the state legislature voted to rename a section of highway in Scraven County. It became the John R. McKini Medal of Honor Highway. A ceremony was held. Veterans attended.

The McKini family accepted the honor on behalf of a man who had never sought recognition for what he did. The highway sign stands today. Drivers pass it without knowing the story behind the name. They do not know about the tent and the sword. They do not know about the machine gun and the 36 minutes. They do not know that the quiet farmer who once lived nearby had saved an entire company through an act of violence and courage that still defies belief.

40 men in 36 minutes. One rifle, one soldier, one morning in the Philippines that should have ended in massacre but ended in something else entirely. Private John McKenna never asked to be a hero. He was a farm boy who joined the army because there was a war. He did what he had to do to survive and to protect the men sleeping around him.

Then he went home and tried to live a normal life. That is the story. That is the legacy. That is John McKini. If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor. Hit that like button. Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications.

We are rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day. Stories about farm boys and privates who save lives with rifles and bare hands. Real people, real heroism. Drop a comment right now and tell us where you are watching from. Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You are not just a viewer.

You are part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served. Just let us know you are here. Thank you for watching and thank you for making sure John McKenna does not disappear into silence. These men deserve to be remembered and you are helping make that

News

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word Dean Martin had…

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later Hong Kong,…

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory

Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory In 1943, the Chinese economy…

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office July 5th, 1945. Harry…

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene The coffee cup was…

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING June 18th, 1957,…

End of content

No more pages to load