Why Roosevelt’s Treasury Official Sabotaged China – The Soviet Spy Who Handed Mao His Victory

In 1943, the Chinese economy was dying. Inflation had crossed 1,000% and was accelerating. Prices doubled every few months. A sack of rice that cost a week’s wages in the morning was often unaffordable by sunset. Soldiers in Chiang Kaishek’s nationalist army watched their wages become worthless before they could spend them.

Farmers refused to sell grain for paper money that lost value by the hour. The black market became the only functioning economy in unoccupied China. The United States government had a solution. Washington had committed in writing to supply $200 million in gold to Chang’s government to stabilize the currency. The gold existed.

It sat in Treasury Department vaults earmarked and ready for shipment. But it never arrived on time. Month after month, the shipment was delayed. Paperwork stalled. Bureaucratic objections materialized from nowhere. Technical concerns about transportation were raised and never resolved. Shiang Kai-shek sent increasingly desperate cables to Washington.

His finance ministers begged their American counterparts for the gold that had been promised. The responses were polite and empty. The gold stayed in the vaults. By the time a fraction of it was finally released, the inflation had become unstoppable. Chang’s government was financially crippled.

His army couldn’t pay its soldiers. His administrators couldn’t fund basic services. The man blocking the gold shipment wasn’t a Japanese sabotur or a bureaucratic incompetent. He was one of the most powerful officials in the United States Treasury Department and he was working for Joseph Stalin. Harry Dexter White was born in Boston in 1892, the youngest of seven children of immigrants who had fled the Russian Empire.

He grew up in a household that valued education above everything else. He fought in France during the first world war as an infantry lieutenant. He came home, earned a PhD in economics from Harvard and joined the Treasury Department in 1934. White was brilliant. His superiors recognized it immediately. Within six years, he controlled the division of monetary research.

By 1941, he was the most influential economist in the federal government, serving as assistant to the secretary with control over all Treasury foreign affairs. Treasury Secretary Henry Morganthaw trusted White completely. Cables went out under Morganthaw’s signature, but the words and the strategy were whites. In 1944, White achieved something extraordinary.

He organized the Breton Woods Conference in New Hampshire where representatives of 44 nations created the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. These institutions would govern global finance for the rest of the century. White designed them both. He dominated the proceedings so thoroughly that he overruled John Maynard Kanes, the most famous economist alive, the architect of the post-war financial order, the man who reshaped global capitalism at a conference table.

He was also a Soviet agent who had been passing classified documents to Moscow since 1935. White’s involvement with Soviet intelligence began almost the moment he arrived in Washington in 1934. He joined what became known as the wear group, a secret cell of communist sympathizers inside the federal government organized by Harold Wear.

The members were young idealistic New Deal economists who believed the depression had proven capitalism’s failure. The group included names that would later become infamous. Alger from the State Department, Lee Presman from agriculture, and Harry Dexter White from Treasury. The wear group wasn’t just a discussion circle. It was a recruitment pipeline for Soviet intelligence.

By 1935, a courier named Whitaker Chambers was collecting documents from White and photographing them for transmission to Moscow. white selected papers that revealed American economic strategy, diplomatic positions, and internal policy debates. A January 1942 assessment by a senior NKVD officer described White as one of the most valuable agents the Soviet Union had in America.

But White was not a disciplined operative following orders. His handler, Vasili Zerubin, reported back to Moscow that White was a very nervous and cowardly person who worried constantly about exposure. White spied out of conviction, not obedience. He believed the Soviet Union represented the future of human civilization.

He believed American and Soviet interests could be harmonized if the right people shaped policy. that made him far more dangerous than a simple document thief. White didn’t just steal secrets. He bent American policy towards Soviet objectives from inside the machinery of government. And Moscow was about to give him his most consequential assignment.

In the spring of 1941, Harry Dexter White sat down for lunch at the old Ebott Grill in Washington, just yards from the White House. Across the table, said a young, nervous Soviet NKVD operative named Vitali Pavlof. The conversation was deliberately casual until Pavlof slid a folded note across the table.

It contained instructions from another Soviet officer White already knew, referred to only as Bill. White read the note carefully. He told Pavlof he was amazed at the concurrence of his own ideas with Bill’s recommendations. The note outlined a strategic priority that was a matter of national survival for the Soviet Union. Germany was preparing to invade Russia.

Stalin feared Japan would simultaneously attack from the east, forcing a two-front war that could destroy the Soviet state. Moscow needed America and Japan to fight each other. If White could push American policy toward confrontation with Tokyo, Japan would strike south toward the Pacific, not north into Siberia.

The operation was cenamed Snow. White went back to the Treasury and began drafting a memorandum for Morganthal. It proposed a set of demands so aggressive that no sovereign nation could accept them. One provision suggested Japan lease 50% of its naval and air forces to the United States. The demand would have caused riots in Tokyo.

That was the point. By November 1941, White had refined his approach into a final document containing 10 aggressive demands. Japan must withdraw from China, Manuria, and Indo-China. Japan must sever its alliance with Germany. The terms were designed to be impossible to accept. White’s language found its way into Secretary of State Cordell Hull’s final dispatch to Tokyo.

Hull’s harsh words transformed what had been diplomatic negotiations into what Japan’s military leadership perceived as an ultimatum. Hull later testified that he took the tough line partly because of a cable from Owen Latimore, another identified Soviet operative serving as Roosevelt’s special adviser to Chiang Kai-shek. Latimore had urged against any accommodation with Japan.

It is beyond dispute that Japan made its decision to attack Pearl Harbor after receiving the dispatch. Japanese military leaders considered it a declaration of war in all but name. On December 7th, 1941, Japanese aircraft struck the American Pacific Fleet at anchor. 2,43 Americans died that morning. Stalin got exactly what he needed.

Japan was now fighting America across the Pacific. There would be no Japanese invasion of Siberia. the Soviet Union could focus entirely on Germany. After Pearl Harbor, Harry Dexter White was promoted to assistant to the Secretary of the Treasury, Morganthau’s right-hand man with control over all foreign economic policy.

He had helped engineer the diplomatic deadlock that made the attack inevitable. Nobody suspected a thing, and now he had access to every classified agreement between the Allied powers. His next operation would target America’s most important Asian ally. White’s promotion gave him access to virtually every classified economic document in the federal government.

He used that access on behalf of Moscow through a spy ring that operated with astonishing carelessness. The Silvermaster group was named after Nathan Gregory Silvermaster, a mid-level government economist who served as its coordinator. Members socialized openly. They discussed classified operations at dinner parties.

Silvermaster photographed stolen documents in his own basement using a camera provided by Soviet intelligence. Elizabeth Bentley, the courier who picked up the film, later marveled at how reckless the group was. But the intelligence they produced was extraordinary. Moscow’s assessment was blunt.

The Silvermaster group delivered the most valuable information coming from any American station. White was the group’s most important source. But he contributed something more dangerous than documents. He used his authority to hire communists and Soviet sympathizers throughout the division of monetary research, building a network inside Treasury that could shape policy from the inside.

Senator William Jenner’s investigation later found that White’s name was used as a reference by other members applying for government service. He hired them, promoted them, and gave them raises. Two of those hires, Solomon Adler and VFrank Co, would execute the most consequential piece of white sabotage.

Their target was the economic survival of nationalist China. In 1941, the Treasury Department posted an economist named Solomon Adler to Chungqing as its official representative in wartime China. Harry Dexter White had arranged the assignment. Adler was another cog in the silvermaster machine working directly under White’s protection.

He had spent 5 years inside Treasury before White handpicked him for the critical mission in China. In Chongqing, Adler’s living arrangements were extraordinary. He shared a house with Chi-Cha Ting, a Chinese communist secret agent who had infiltrated Chiang Kai-shek’s financial bureaucracy. Their third housemate was John Stewart Service, a State Department officer who would later be arrested in the Amorasia espionage case, a Treasury representative, a communist agent, and a compromised diplomat, all under one roof in the wartime capital. Adler’s reports

to Washington were circulated widely and carried the weight of on the ground expertise. Those reports consistently argued against financial assistance to Chang’s government. Inflation was structural. Corruption was endemic. Gold shipments would be wasted. Back in Washington, the third point of the triangle was VFR Co, who now directed White’s division of monetary research.

His Venona code name was Peak. White, Adler, and Co. performed a coordinated operation. Reports from the field in Chongqing aligned perfectly with analysis from headquarters in Washington, creating the illusion of independent experts reaching the same conclusion. The Senate Internal Security Subcommittee later called their concentration in China policy positions anything but accidental.

By December 1944, the delays had shifted from passive obstruction to active sabotage. White issued a memorandum to Morganthal arguing the gold shipment would be ineffective. The inflation had structural causes. He claimed gold alone couldn’t fix it. Further study was needed. Adler and co backed him from Chung King and Washington respectively.

The bureaucratic consensus within Treasury became unanimous. The gold should wait. Chiang Kaishek himself later accused White and his staff of deliberately sabotaging Chinese economic policy. His finance ministers documented the obstruction in cable after cable. Nobody in Washington listened. By the time fragments of the loan were finally released, the damage was irreversible.

Hyperinflation had shattered public confidence in the nationalist government. Soldiers deserted because their pay couldn’t buy rice. Administrators became corrupt because their salaries were worthless. Mao’s communist forces didn’t need to defeat Chiang on the battlefield. They just needed to wait while his government rotted from within.

The gold that could have prevented that collapse sat in American vaults while a Soviet agent wrote memos explaining why it should stay there. China was not White’s only target. In 1944, the Allied powers prepared occupation currency for postwar Germany. The printing plates were produced in Washington under Treasury supervision. The Soviet Union demanded its own set of plates to print currency for its occupation zone.

The request was extraordinary. Giving a foreign government the ability to produce unlimited quantities of a shared currency was economic suicide. Military officials and Treasury bureaucrats objected. White overrode them all. The Soviets printed marks with abandon. They flooded their zone with unbacked currency, creating hyperinflation and a massive black market.

American taxpayers absorbed the cost, $250 million. Elizabeth Bentley testified in 1953 that White had arranged the plate transfer following instructions relayed through the Silvermaster network. Soviet archives confirmed her account. An April 1944 NKVD memorandum stated that the plates had been delivered following our instructions transmitted through Silvermaster via White.

White also co-authored the Morganthal plan which proposed stripping Germany of all industrial capacity. Secretary of War Henry Stimson called it a Carthaginian attitude, a reference to Rome’s total annihilation of Carthage. White didn’t want Germany defeated. He wanted it erased as an industrial power. Critics noted the plan would drive an impoverished Germany straight into Stalin’s arms.

Every major policy whitetouched served Soviet strategic interests. The pattern was invisible to anyone who wasn’t looking for it, and nobody was looking. White’s treasury operation was one front in a broader campaign that had penetrated American China policy at every level. The State Department’s China hands, John Stewart Service, and John Davies sent dispatches portraying Mao’s forces not as revolutionaries, but as agrarian reformers, harmless democrats rather than Soviet proxies.

Owen Latimore, the same Soviet connected adviser who had pushed Hull toward the ultimatum before Pearl Harbor, was still shaping Roosevelt’s China policy from the inside. In December 1945, President Truman sent George Marshall to broker peace between nationalists and communists. Marshall imposed an arms embargo on Chang from July 1946 to May 1947.

10 months without American weapons at the moment, Soviet captured Japanese equipment was flooding into Mao’s forces in Manuria. In 1947, General Albert Wedomire toured China and produced a report recommending urgent military and economic aid to Chang. Marshall suppressed it. The report wasn’t published until years after China had fallen.

The Truman Doctrine promised to defend free nations from communist takeover. Greece received battalion level military advisers. Turkey received economic aid. China received an arms embargo and lectures about coalition government. Chang expected the containment policy would extend to Asia. It never did. On October 1st, 1949, Maoadong stood at the gate of heavenly peace in Beijing and proclaimed the People’s Republic of China.

The most populous nation on earth had fallen to communism. The question that would consume American politics for a generation detonated across Washington. Who lost China? On November 7th, 1945, Elizabeth Bentley walked into an FBI field office in New York and talked for eight hours. Her 31page statement named dozens of Soviet agents inside the American government.

Harry Dexter White was second on her list. FBI Director Hoover sent a handdelivered letter to the White House the very next day. It named White prominently. On December 4th, the bureau sent a comprehensive report titled Soviet Espionage in the United States. Truman read the warnings. Then on January 23rd, 1946, he nominated Harry Dexter White to be the first American executive director of the International Monetary Fund.

The FBI tried again. On February 4th, 1946, it delivered a 28-page memorandum specifically detailing the espionage case against White. The memo arrived at the White House 2 days before the Senate voted on his confirmation. The Senate was never informed of the allegations. White was confirmed on February 6th. Truman later claimed he had separated White from government service promptly.

This was a lie. White served at the IMF until he abruptly resigned in June 1947. The most damaging agent in the American government had been identified, reported, and rewarded. On July 31st, 1948, Elizabeth Bentley testified publicly before the House Committee on Unamerican Activities. She named White as part of the Soviet Espionage Network.

Three days later, Whitaker Chambers took the stand. He produced a handwritten memo in White’s own handwriting containing classified State Department information. White requested the opportunity to appear. He arrived on August 13th, having recently suffered a heart attack. He looked frail. The hearing room was stifling. He asked the committee for periodic rest breaks during his testimony.

sweat gathered on his forehead, not just from the heat, from the weight of a decade of lies pressing down on him in a room full of cameras. White was defiant. He told the committee that the principles in which he believed made it impossible for him to ever do a disloyal act. He challenged his accusers with the intellectual confidence that had once overruled Canes at Bretonwoods.

He left Washington after testifying and drove to his farm in Fitz William, New Hampshire. On August 16th, just 3 days after his appearance before Congress, Harry Dexter White was found dead. He was 55 years old. The official cause was a heart attack. Questions about the circumstances persisted for decades.

The man who had been HUAC’s primary target was suddenly beyond the reach of any courtroom. With White, the committee shifted its focus entirely to Alger. But the larger story, the sabotage of China, the Pearl Harbor ultimatum, the German currency plates disappeared into classified archives where it would remain locked for nearly half a century.

The evidence that would have convicted Harry Dexter White was hidden inside one of the most closely guarded programs in American intelligence. The Venona project had been decryptting Soviet cables since 1943. NSA cryptographers identified White under three code names: jurist, lawyer, and Richard.

The cables documented meetings with Soviet handlers and discussions about payment for his services. An FBI memorandum dated October 15th, 1950 positively identified White as the source code name jurist. But Venona was so sensitive that its existence was concealed even from presidents. The decrypts couldn’t be used in court without revealing the program.

Then the Cold War ended. The archives opened. In 1995, the NSA declassified the Venona Decrypt. In 1997, the bipartisan Moahan Commission on government secrecy delivered its judgment. The complicity of Alger of the State Department seems settled, as does that of Harry Dexter White of the Treasury Department.

Soviet archives provided the final confirmation. The Vasilv notebooks copied from KGB files documented White as a recruited agent with handler meetings, code names, and operational directives laid out in detail. But the most devastating proof didn’t come from any archive or intercepted cable.

It came from what White’s accompllices did after the network was exposed. Solomon Adler resigned from Treasury in 1950 just ahead of a loyalty investigation. He returned to England, was dnaturalized when his passport expired, and moved to Communist China. He spent 20 years working for the Chinese Communist Party’s central external liaison department, an intelligence organization.

He translated Mao’s works into English. He met with Maoadong and Joe Enli personally as an economic adviser. The man who had sabotaged American financial aid to Chiang Kai-shek from his house in Chongqing had gone home to the regime. His betrayal helped create. He died in Beijing in 1994. Franco’s path was identical.

Blacklisted and denied a passport, he fled to China during the Great Leap Forward. He wrote articles justifying Mao’s rectification campaign while millions starved. He translated the selected works of Mao Zadong. During the Cultural Revolution, when foreigners were beaten and imprisoned, intelligence chief Kang Shang personally shielded Co from the Red Guards, a privilege almost no one received.

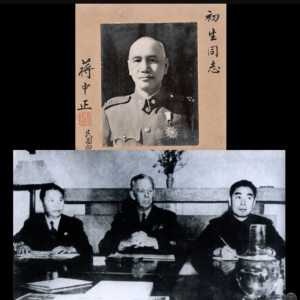

Co died in Beijing in 1980. In 1965, a photograph was taken in Wuhan. It shows Soul Adler and Frank Co standing beside Mao Zadong smiling. Two former Treasury officials who had blocked American gold to Chiang Kaishek. Standing next to the dictator whose victory they had spent years engineering from inside the American government.

While American soldiers were freezing in Korean trenches fighting the army these men helped build, Adler and Co were posing for photographs with the man who sent that army. They never needed to confess. The photograph said everything. Within a year of Mao’s victory, Chinese forces crossed the Yalu River into Korea.

36,000 Americans died in that war. No single spy lost China. But Harry Dexter White made sure America’s response came too late. Shaped by men who answered to Moscow. The gold stayed in the vaults. The arms embargo held. The warnings were filed and forgotten. The Cold War is often remembered as a nuclear standoff. But the first great battle wasn’t fought with missiles.

It was fought with memos in quiet offices by men like Harry Dexter White. And by the time America realized the war had started, they had already lost the first round.

News

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word

A Funeral Director Told a Widow Her Husband Goes to a Mass Grave—Dean Martin Heard Every Word Dean Martin had…

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later

Bruce Lee Was At Father’s Funeral When Triad Enforcer Said ‘Pay Now Or Fight’ — 6 Minutes Later Hong Kong,…

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office

Truman Fired FDR’s Closest Advisor After 11 Years Then FBI Found Soviet Spies in His Office July 5th, 1945. Harry…

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene

Albert Anastasia Was MURDERED in Barber Chair — They Found Carlo Gambino’s FINGERPRINT in The Scene The coffee cup was…

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING

White Detective ARRESTED Bumpy Johnson in Front of His Daughter — 72 Hours Later He Was BEGGING June 18th, 1957,…

A Rival Spy Used a Wiretap on Gambino — He Found His Own Car Filled to the Roof With Expanding Foam

A Rival Spy Used a Wiretap on Gambino — He Found His Own Car Filled to the Roof With Expanding…

End of content

No more pages to load